During the reign of Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin, the gulags imprisoned millions of political prisoners — brutalizing and killing many of them.

Library of CongressPrisoners at a gulag camp in Siberia. Date unknown.

For decades, a single word could strike fear into the hearts of many Soviet citizens: “gulag.” At its peak from the 1920s to the 1950s, this sprawling network of forced labor camps held millions of political prisoners, rebellious peasants, petty criminals, and ordinary citizens who had been accused of being disloyal to the government. And while some survived the horrific experience, many died from malnutrition, overwork, or abuse.

Started by Vladimir Lenin, and expanded by Joseph Stalin, gulags made up a defining part of life in the Soviet Union. As many as 30,000 camps operated across the USSR, where prisoners served years-long sentences for offenses as innocuous as making a drunken joke or showing up late to work.

In these camps, prisoners suffered through 14-hour work days, frigid-cold weather, lack of food, sexual abuse, and random executions. Under the harsh eye of camp guards, they forged canals with their bare hands, choked on dust in mines, and struggled to dig pits in the frozen ground.

So, how did the Soviet gulag begin? How did it expand? And how did these brutal and violent forced labor camps finally shut down?

How The Gulag Prison System Began

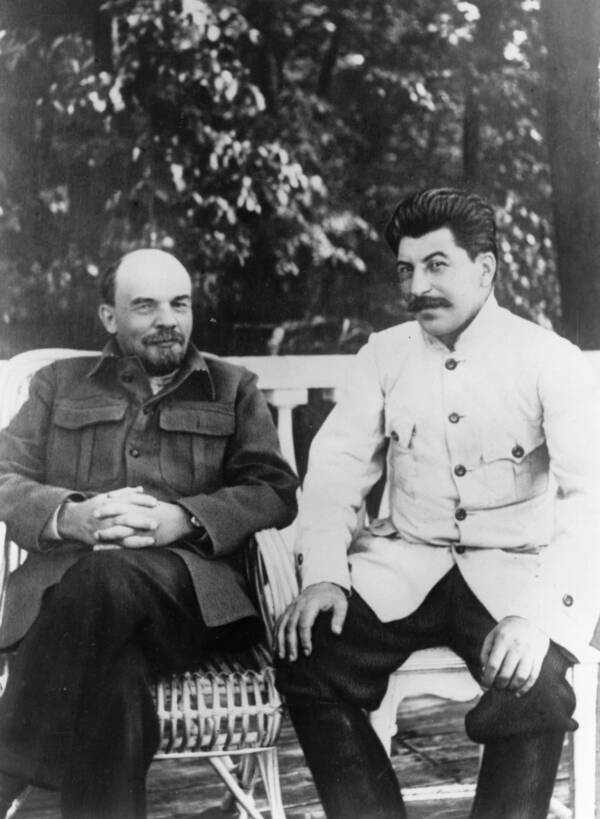

Keystone/Getty ImagesThe gulag system started under Vladimir Lenin (left), but was greatly expanded by Joseph Stalin (right). 1922.

Though the story of the gulag is intrinsically tied with Joseph Stalin, the idea for this system of forced labor camps first came from his predecessor, Vladimir Lenin. According to the Gulag Online, Lenin and the Bolsheviks came up with the concept of “class enemies” when they took power in 1917.

Convinced they needed forced labor camps to contain such dissidents, the new Soviet government created a prison system on April 15, 1919. By 1921, according to History, some 84 camps had opened up across the USSR.

But then, Lenin died in 1924 — and Joseph Stalin came to power. Determined to industrialize his country, Stalin instituted a series of five-year plans and strategies like collectivization, or collective farming. The country’s prisons, he believed, could power the USSR’s growth — and they were a convenient place to throw anyone who protested against his policies.

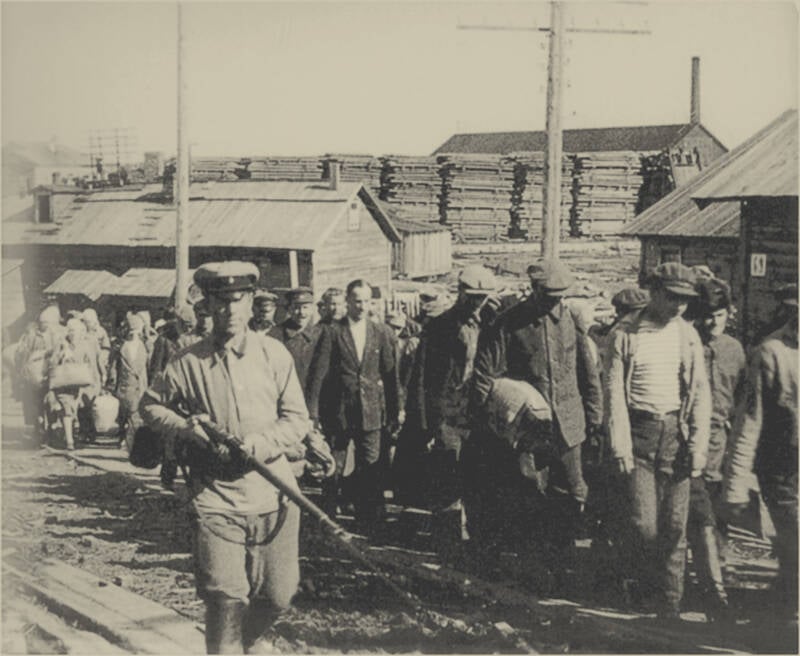

Wikimedia CommonsGulag prisoners transport lead-zinc ore at Vaygach Island. Circa 1931-1932.

Before long, the make-up of the camps started to change dramatically. Peasants — called kulaks — were soon sentenced to forced labor in droves for refusing to give up their farms and join a collective. According to the Chicago Public Library, other peasants could be imprisoned for telling an anti-Stalin joke, taking food from a collective farm, or being late to work.

By the 1930s, the prisons had a formal name: Glavnoye Upravleniye Lagerey (Main Camp Administration), or GULAG. And they also had more prisoners than ever. As Stalin instituted his Great Purge from 1936 to 1938, his government incarcerated — and executed — countless dissenting members of the Communist Party, opposing military officers, anti-Stalinist government officials, and ordinary people who were suspected of being disloyal.

Some 30,000 camps soon operated across the USSR, where between 15 and 18 million prisoners toiled under harsh conditions for years. So, what was life like for the millions of people who were imprisoned inside a gulag?

Life Inside The Soviet Gulag System

Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty ImagesGulag prisoners, pictured at the Solovki prison camp.

Unsurprisingly, life in the gulag was brutal. Forced to work long hours in bleak conditions, prisoners also suffered from starvation, disease, and violence from camp guards — as well as their fellow prisoners.

“The Gulag was conceived in order to transform human matter into a docile, exhausted, ill-smelling mass of individuals,” wrote gulag prisoner Jacques Rossi, a communist writer arrested during Stalin’s Great Purge.

Gulag prisoners frequently worked on ambitious Soviet projects, like the White Sea-Baltic Canal or the Kolyma Highway, often with few tools. During the construction of the canal, for example, prisoners were forced to work with pickaxes or their hands, making the work bone-crushingly difficult.

To make matters worse, prisoners were given rations of food based on how much work they’d accomplished each day. Gulag History reports that prisoners who were unable to meet their daily quotas didn’t get a full ration of food, which meant that many of these people slowly starved to death. But even prisoners who managed to meet their quotas didn’t eat well.

Wikimedia CommonsGulag prisoners working on the White Sea–Baltic Canal in 1932. Thousands of people died during its construction.

“We were ready to cry for fear that the soup would be thin,” wrote former gulag prisoner Varlam Shalamov, who later described his experience in a collection of short stories called Kolyma Tales.

“And when a miracle occurred and the soup was thick we couldn’t believe it and ate it as slowly as possible. But even with thick soup in a warm stomach there remained a sucking pain; we’d been hungry for too long.”

Another prisoner named Kazimierz Zarod, a Polish civil servant sent to the gulag after the Soviets invaded Poland in 1939, remembered how jealously he and other inmates guarded their meager rations in the camp. According to the Daily Mail, he described the bread as “the source of Gulag life.”

“If a prisoner stole clothes or tobacco and was discovered, he could expect a good beating from his fellow inmates,” Zarod recalled. “But the unwritten law of this camp was that anyone caught stealing another man’s bread earned a death sentence. An ‘accident’ was not difficult to arrange in the forest.”

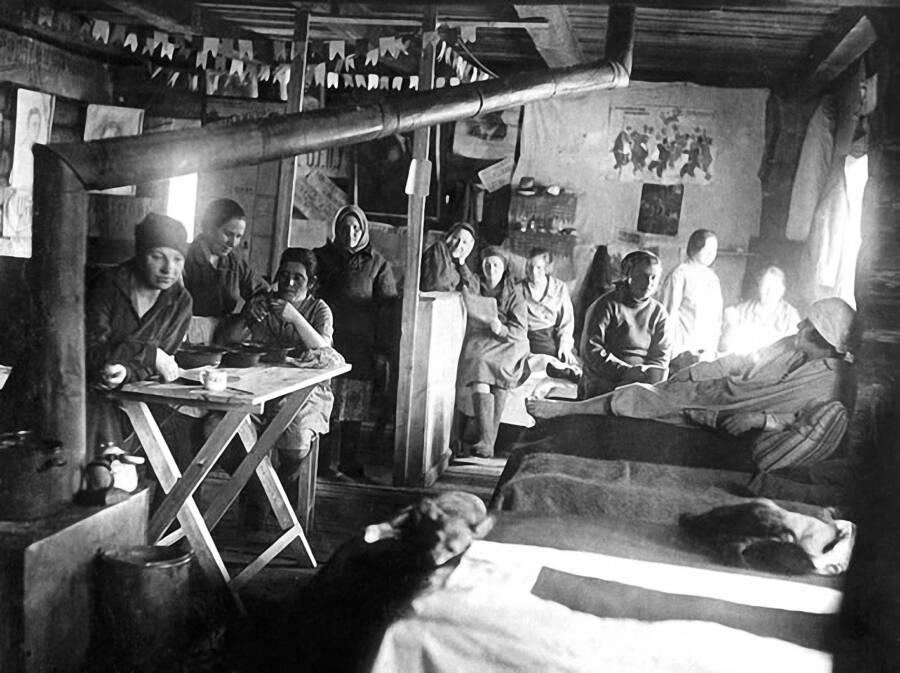

Laski Diffusion/Getty ImagesFemale gulag prisoners in their shack in the Vorkuta Gulag. 1945.

Life in the gulag could be especially brutal for female prisoners, who were subjected to sexual abuse from camp guards and male prisoners alike. One survivor, Elena Glinka, recalled a mass rape called the “Kolyma tram.”

“The men rushed the women and began to haul them into the building, twisting their arms, dragging them through the grass, brutally beating any who resisted,” Glinka remembered, per the Daily Mail.

Glinka continued, “A line of about 12 men formed by each woman, and the Kolyma tram began. When it was over, the dead women were dragged away by their feet; the survivors were doused with water from the buckets and revived. Then the lines formed up again.”

Women who were pregnant, or who became pregnant at a gulag, often never saw their children again after they delivered them. Gulag History reports that gulag officials sometimes took the children and put them in orphanages. Other times, the children died under the care of the officials.

“It was the worst cruelty,” former prisoner Vera Golubeva, who arrived at the gulag eight months pregnant without knowing why she’d been incarcerated, remembered, according to The Atlantic. Her baby, a boy, died days after birth.

An Open Secret In The Soviet Union

Wikimedia CommonsMen incarcerated at the Vaygach Island gulag stand around the coffin of a miner who died. 1931.

Given the harsh conditions inside the gulag prisons, it’s no surprise that people died by the thousands. History reports that some 10 percent of gulag prisoners died every year, and Gulag Online estimates that at least 1.5 million people died while incarcerated in the Soviet prison camps.

Within the USSR, the camps were something of an open secret. According to the Chicago Public Library, people who returned home after their prison terms often brought stories about the gulag with them, and inmates within gulags could sometimes correspond with their families at home.

“[The gulag] created fear,” Anne Applebaum, the author of Gulag: A History, explained in an interview with The Atlantic. “It was very spread out, it had branches all over the Soviet Union and everybody knew about it. Everybody was aware that it existed. It wasn’t some kind of hidden part of society. It functioned as something that would scare people.”

By the 1950s, Joseph Stalin seemed prepared to imprison even more people in the gulag. According to The New York Times, he ordered the construction of four new prison camps in anticipation of a second Great Purge, during which he apparently planned to target Soviet Jews. But shortly after the dictator had several Kremlin doctors arrested, Stalin died in 1953.

With his death, the era of the gulag started to come to an end. But not all of these forced labor camps closed their doors right away.

How The Forced Labor Camps Lingered In The Soviet Union

Bettmann/CORBIS/Bettmann ArchiveNikita Khrushchev, a critic of the gulags, became the Soviet premier in 1958.

According to History, millions of people were released from the gulag after Joseph Stalin’s death in 1953. And five years later, in 1958, Nikita Khrushchev became the Soviet premier. A critic of the gulags, he promptly began a policy of “de-Stalinization” and a period of leniency called the “Khrushchev Thaw.”

But that didn’t mean that the gulags completely disappeared.

According to History, the gulag continued on in different ways for about 30 more years. In the 1970s and 1980s, camps across the Soviet Union held criminals, democratic activists, and anti-Soviet nationalists. In 1972, a couple of new camps even opened to imprison more anti-Soviet agitators, including writers, poets, dissidents, and priests.

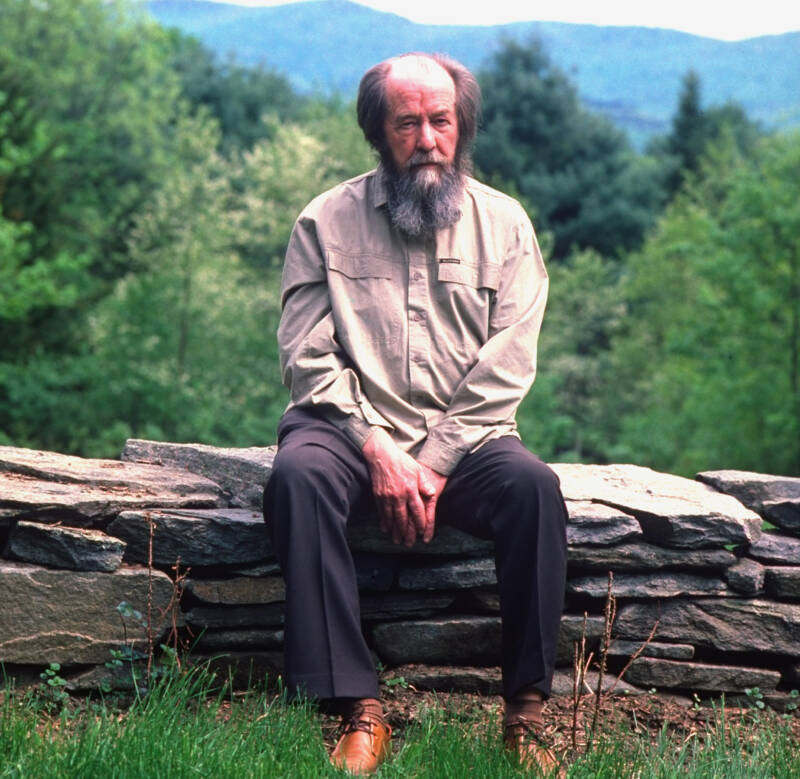

In any case, Soviet society certainly wasn’t ready to closely examine what had happened during the height of the gulags. When Russian writer Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn published The Gulag Archipelago, one of the first publicized accounts of the horrors of the gulag, in 1973, he lost his Soviet citizenship and was forced to flee the country. Solzhenitsyn didn’t return until 1994, a few years after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

“What would things have been like if every Security operative, when he went out at night to make an arrest, had been uncertain whether he would return alive and had to say goodbye to his family?” Solzhenitsyn famously demanded in his explosive work.

“Or if, during periods of mass arrests, as for example in Leningrad, when they arrested a quarter of the entire city, people had not simply sat there in their lairs, paling with terror at every bang of the downstairs door and at every step on the staircase, but had understood they had nothing left to lose and had boldly set up in the downstairs hall an ambush of half a dozen people with axes, hammers, pokers, or whatever else was at hand?”

It wasn’t until the late 1980s that Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev began to officially end the gulag system — possibly in part because his own grandparents had been victims of the forced labor camps.

The Haunting Legacy Of The Gulag

Steve Liss/Getty ImagesThe Gulag Archipelago author Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn in 1989, two years before the collapse of the Soviet Union.

So, what did the gulag actually accomplish, if anything? Did all that forced labor — massive projects paid for with blood, sweat, and tears — industrialize the Soviet Union as Joseph Stalin had hoped?

Yes, and no. Gulag Online reports that some projects, like the “Dead Road” project and a railway to Sakhalin Island, were immediately suspended following Stalin’s death. Others, like the White Sea-Baltic Canal, were finished — but encountered issues almost immediately upon completion.

It was soon clear that the canal was much too narrow and shallow to be used properly. The waterway needed to be deepened and widened several times throughout the years so that ships could successfully pass through. What’s more, the canal was completed at a terrible cost — as an estimated 25,000 people lost their lives while working on the project.

All in all, many modern historians don’t believe that the gulag had a meaningful impact on the economy of the Soviet Union. Though it did offer a seemingly endless supply of cheap labor, many projects had clear problems that came along with using a weakened and subjugated workforce. The gulag mainly seemed to operate as a way to punish Stalin’s real and imagined enemies — and prevent any other potential naysayers from speaking up.

And what of the people whose lives were impacted — or cut short — by the gulag? Applebaum notes that the true number of people who were killed by Stalin in gulags is unknown because every death had a ripple effect.

“No official figures, for example, can possibly reflect the mortality of the wives and children and aging parents left behind since their deaths were not recorded separately,” Applebaum wrote in Gulag: A History.

Applebaum continued, “During the war, old people starved to death without ration cards: had their convict son not been digging coal in Vorkuta, they might have lived. Small children succumbed easily to epidemics of typhus and measles in cold, ill-equipped orphanages: had their mothers not been sewing uniforms in Kengir, they might have lived too.”

Likewise, the people who survived their incarceration never fully recovered from what had happened in the gulag. When Vasily Kovalyov, a gulag survivor, died in 2018, a local news site reported: “Until his last breath he never forgot what the Soviet Union did to millions of people, who endured the camps, leaving their best years, their health and their lives there.”

Today, the memory of these forced labor camps is a somewhat complicated one in Russia. In 2015, The Guardian reported that some Russians still consider the gulag a necessary evil during the era of the Soviet Union. And worryingly, in 2021, Reuters compared the incarceration of modern-day political prisoners in Russia to the gulag camps. Tellingly, many survivors of the Soviet gulag are still afraid to talk about their experiences today.

But perhaps the true — and chilling — legacy of the gulag was best summed up by Solzhenitsyn in his seminal work, The Gulag Archipelago.

“Alas, all the evil of the twentieth century is possible everywhere on earth,” Solzhenitsyn wrote, adding: “Yet, I have not given up all hope that human beings and nations may be able, in spite of all, to learn from the experience of other people without having to go through it personally.”

After reading about the history of the Soviet gulags, look through these Soviet propaganda posters from the height of the Cold War. Then, delve into the strange mystery that surrounds the death of Joseph Stalin.