Even though the Second Amendment is a supposedly "inalienable" right, our interpretation of it has changed over the years.

In the United States of America, there is no government-sanctioned definition of a mass shooting — the crime that has polarized the already contentious debate over firearms regulations like nothing else in the history of gun control in America.

In lieu of a formal definition, some agencies adopt the FBI’s standard for mass murder: an event where an individual takes the lives of “four or more people in a single incident (not including himself), typically in a single location.”

Others prefer different metrics that take into account injuries, for example, or exclude cases of domestic and gang violence. As a result, it can be difficult to compare numbers from different studies.

But on one point, at least, the research agrees: in the wake of a number of public tragedies, mass shootings are more a part of the public’s consciousness than ever before.

Over the course of his two-term presidency, Barack Obama was made visibly haggard by eight years that saw mass shootings of shocking proportions at Orlando, Florida; Newton, Connecticut; and San Bernardino, California — to name only a few.

2018 began with the Parkland school shooting and concluded with a total of 340 mass shootings, according to the Gun Violence Archive, which considers a mass shooting any incident of gun violence in which 4 or more are shot or killed, not including the shooter.

These kinds of shootings are a distinctly new phenomenon — and they’ve ushered in a new chapter in the history of gun control in America.

Over the years, many gun control proponents have blamed the recent spate of mass shootings on lax regulations and ineffective legislation regarding the sale of guns.

Gun rights advocates argue with equal force that their right to own a weapon cannot be denied and that the battle for gun safety should not remove guns from civilian hands.

The history of gun control in America, however, shows that the truth falls somewhere in between.

The Origin Of Mass Shootings In America

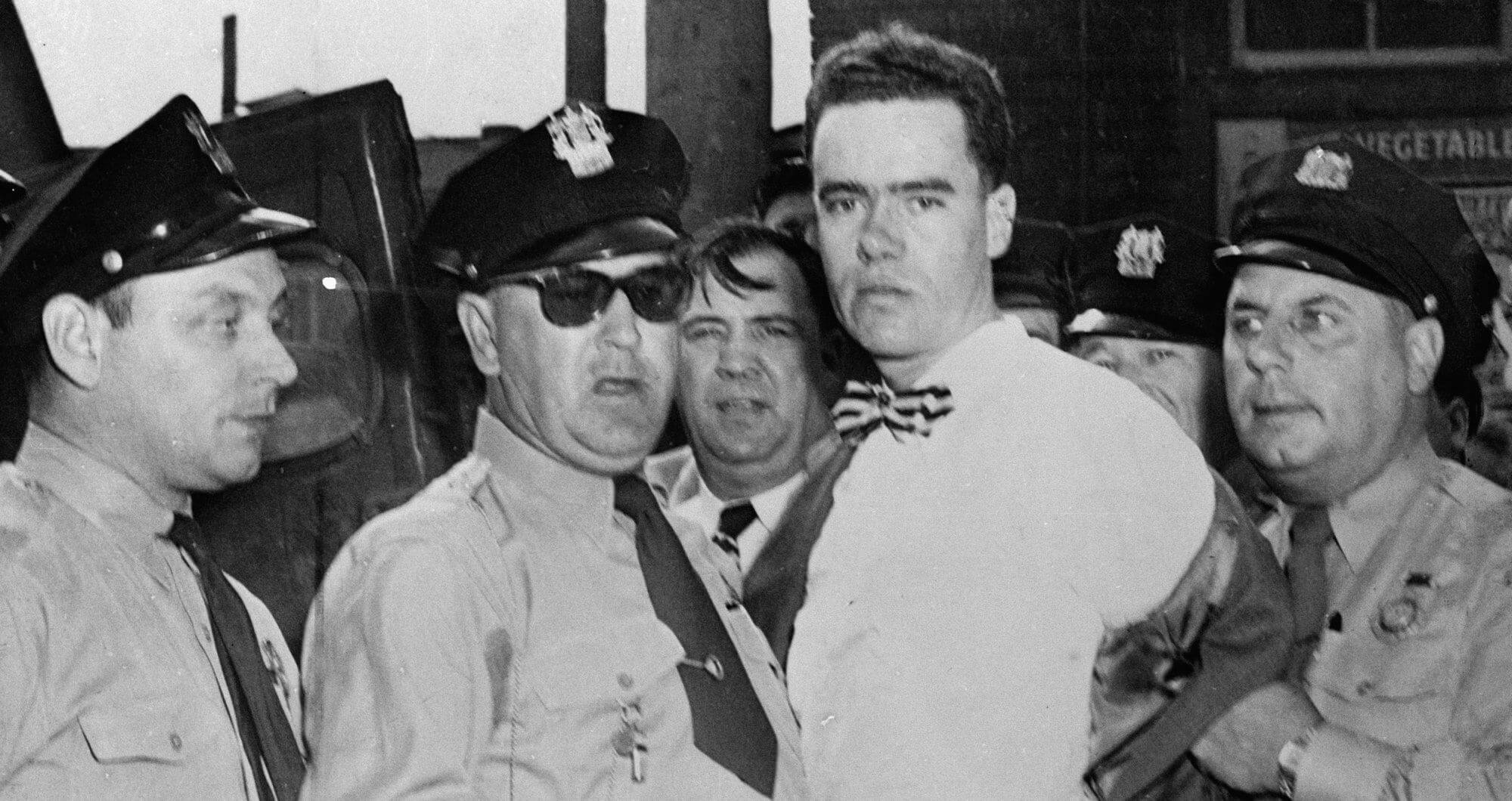

Howard Unruh, on being arrested by Camden police.

The first mass shooting to break into the American consciousness on a large scale occurred in 1949 in Camden, New Jersey, when a 28-year-old World War II veteran named Howard Unruh opened fire in his neighborhood, killing 13 people.

The conflict that gave rise to the incident was small: a gate had been stolen from Unruh’s yard. He grabbed a German Luger pistol from his room, loaded it, and shot over a dozen people.

The incident was the culmination of years of trouble for Unruh. The New Jersey resident had a history of mental instability and had become something of a recluse in the months leading up to the killings.

He was paranoid, and perhaps it wasn’t unfounded: he’d been taunted about his supposed homosexuality and hadn’t been able to finish his university studies after being honorably discharged from the military.

Unruh hadn’t gotten along with his neighbors, and after the killings, police discovered a diary entry in which he’d named individuals and noted “retal” — retaliation. Some of the dead were on his list.

After shooting 13 people in 20 minutes with a gun he had purchased in Philadelphia, Unruh entered an hour-long stand-off with the police, who did not shoot him. Instead, he was taken into custody alive and served the rest of his life in prison, dying in 2009 at the age of 88.

The media called his spree the “Walk of Death.”

Early Gun Control History In America

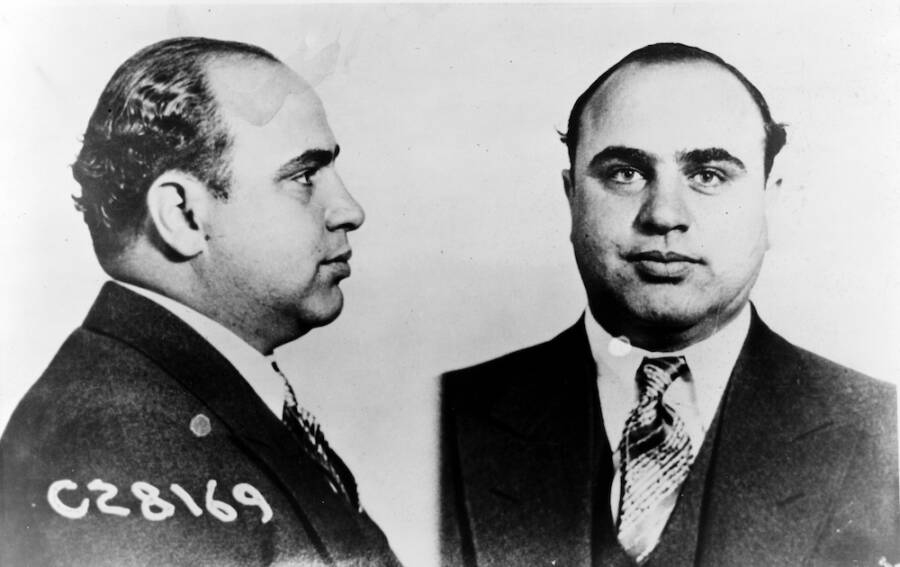

Wikimedia CommonsAl Capone’s mug shot, taken June 17, 1931.

Though the New Jersey mass shooting was a landmark in the public consciousness, it wasn’t the beginning of the history of gun control in America.

Twenty odd years before the Camden neighborhood shooting, the violence of Al Capone and his cohorts ushered in important gun legislation: starting in 1934, all gun sales had to be recorded in a national registry.

Four years later, FDR prohibited the sale of guns to individuals indicted or convicted of violent crimes and began requiring that interstate gun dealers obtain a license to sell.

Over the next thirty years, legislation continued to tighten restrictions on civilian gun use, with the most substantial revision of the laws coming after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy by Lee Harvey Oswald.

Oswald purchased the rifle he used from the NRA’s mail-order catalog, leading Congress to pass the Gun Control Act of 1968, which prohibited the sale of guns by mail-order and raised the age of legal purchase to 21. It also banned all convicted felons, drug users, and individuals found mentally incompetent from owning a gun.

Wikimedia CommonsLee Harvey Oswald, brandishing a rifle in his backyard. March 1963.

At this point, the NRA didn’t even oppose the ban on ordering guns from their catalog. Said NRA Executive Vice President Franklin Orth during the committee hearings:

“We do not think that any sane American, who calls himself an American, can object to placing into this bill the instrument which killed the president of the United States.”

The Rise Of The National Rifle Association

Flickr / Michael VadonWayne Lapierre, Executive Vice President and Chief Executive of the National Rifle Association since 1991.

Over the next twenty years, though, the NRA changed its tune, and the history of gun control in America took a dramatic turn once again.

In the 1980s, the NRA lobbied to equate gun ownership with American freedom and used its sizable influence to pressure politicians into supporting its causes.

It suggested that the restrictions imposed by the Gun Control Act of 1968 unfairly penalized law-abiding citizens for minor regulatory infringements, rather than protecting them.

Lobbying hard for the 1986 Firearms Owners’ Protection Act, which repealed many of the mandates set forth by the Gun Control Act of 1968, the NRA succeeded in enacting a largely self-enforcing, comparatively lax set of regulations that included the reintroduction of interstate sales of firearms and a reduction in the number of gun dealer inspections.

The new law also prohibited the United States government from keeping a national registry of gun owners.

Central to the NRA’s argument was the Second Amendment, which reads as follows: “A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.”

The NRA leadership interpreted this to mean that all individuals have a right to bear arms.

This stands in contrast to another school of legal thought, which interprets the amendment to mean that a state has a right to defend itself with the use of a militia made up of citizens with firearms — an understanding that doesn’t offer a carte blanche to any citizen who wants any kind of gun.

The History Of Gun Control In America In The Modern Age

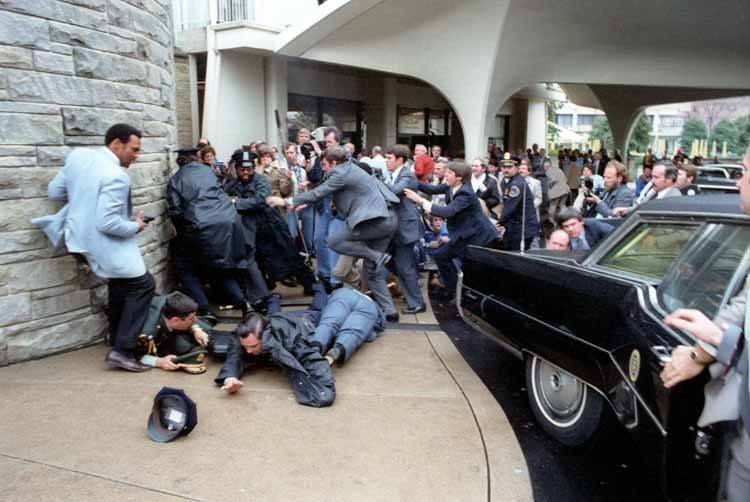

James Brady and Thomas Delahanty lie wounded on the ground following an assassination attempt on President Reagan.

And so the tug of war that is the modern debate over gun control began.

In 1993, background checks were instituted as a precursor to gun ownership, which came as part of The Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act.

This act was named after James Brady, a man shot by John Hinckley Jr. during a 1981 attempt to assassinate Ronald Reagan. Hinckley purchased the gun at a pawn shop using a false address after he had been arrested days earlier for trying to board an airplane with several handguns.

Under the new law, background checks were logged in the National Instant Crime Background Check System (NICS), which is maintained by the FBI. If a person met one of the following criteria, he or she would not be able to purchase a firearm:

- Has been convicted in any court of a crime punishable by imprisonment for a term exceeding one year;

- Is a fugitive from justice;

- Is an unlawful user of or addicted to any controlled substance;

- Has been adjudicated as a mental defective or committed to a mental institution;

- Is an alien illegally or unlawfully in the United States;

- Has been discharged from the Armed Forces under dishonorable conditions;

- Having been a citizen of the United States, has renounced U.S. citizenship;

- Is subject to a court order that restrains the person from harassing, stalking, or threatening an intimate partner or child of such intimate partner, or;

- Has been convicted in any court of a misdemeanor crime of domestic violence.

The NRA fought back, calling the legislation unconstitutional and spending millions of dollars in an attempt to defeat it.

After the NRA funded lawsuits in several states, the Supreme Court took the case and deemed one provision — that which compelled state and local law enforcement officials to perform background checks — unconstitutional on the grounds of the Tenth Amendment.

The law was kept intact in spite of the ruling, but in 1998 a few alterations were made when the NICS went online. Background checks were largely instantaneous, meaning that the five-day wait period was a thing of the past.

Mass Shootings: A Cultural Or Legal Problem — Or Both?

Wikimedia Commons / M&R PhotographyA gun show in America.

Between 1998 and 2014, more than 202 million Brady background checks have been conducted. A remarkable 1.2 million firearms purchases were blocked, with the most common reason for denial being previous felony convictions.

Violators are rarely convicted, however, and studies of the law’s efficacy show that while there has been a reduction in suicides due to Brady background checks, gun homicides have not fallen.

The guns in question are usually handguns, but in recent years focus has shifted to the acquisition of semi-automatic weapons — the newest challenge in the history of gun control in America.

In 1994, the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act placed a ten-year ban on the production of semi-automatic assault weapons and specified 19 prohibited models. This law also banned possession of newly manufactured magazines holding more than ten rounds of ammunition.

The law did not, however, apply to weapons already in possession, and once the ban on production was lifted in 2004, gun manufacturers found it relatively easy to adapt the models to avoid prohibition.

The following year, President George W. Bush signed a bill into law that freed gun manufacturers of legal responsibility for the negative effects of their products, further distancing manufacturers from the consequences of their work.

In October of 2015, the New York Times ran an infographic that showed how several mass shooters acquired their guns and what type of gun they used during the attacks.

The article was a powerful indictment of the laws surrounding gun control today: the vast majority of the guns used were purchased legally — many of them semiautomatic rifles or handguns.

Still, some scholars insist that the real issue is not one of legislation, but rather one of culture. Perhaps, they state, mass shootings are not due to lax laws (and are not, in fact, on the rise); perhaps the violence arises from entrenched cultural attitudes — and founding principles — that legal mechanisms will have a hard time shaking.

This is maybe the most frightening thing about it all — as James Alan Fox posited in a study he coauthored at Northeastern University, “Mass murder just may be a price we pay for living in a society where personal freedom is so highly valued.”

Want to know more about the history of gun control in America? Learn about the ten deadliest mass shootings in U.S. history. Then read up on five gun control facts that both sides keep getting wrong.