In 1979, Hannelore Schmatz achieved the unthinkable — she became the fourth woman in the world to reach the summit of Mount Everest. Unfortunately, her glorious climb to the mountain's peak would be her last.

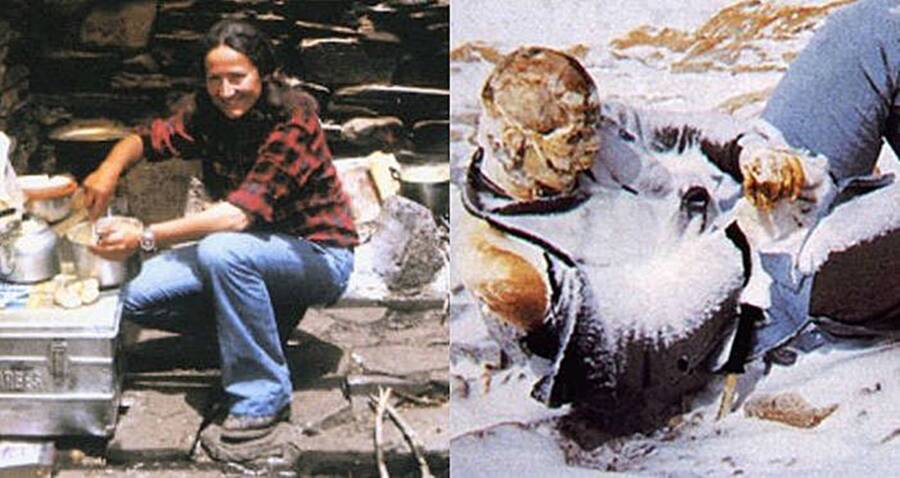

Wikimedia Commons/YoutubeHannelore Schmatz was the fourth woman to summit Mount Everest, and the first woman to die there.

German mountaineer Hannelore Schmatz loved to climb. In 1979, accompanied by her husband, Gerhard, Schmatz embarked on their most ambitious expedition yet: to summit Mount Everest.

While the husband-and-wife triumphantly made it to the top, their journey back down would end in a devastating tragedy as Schmatz ultimately lost her life, making her the first woman and first German national to die on Mount Everest.

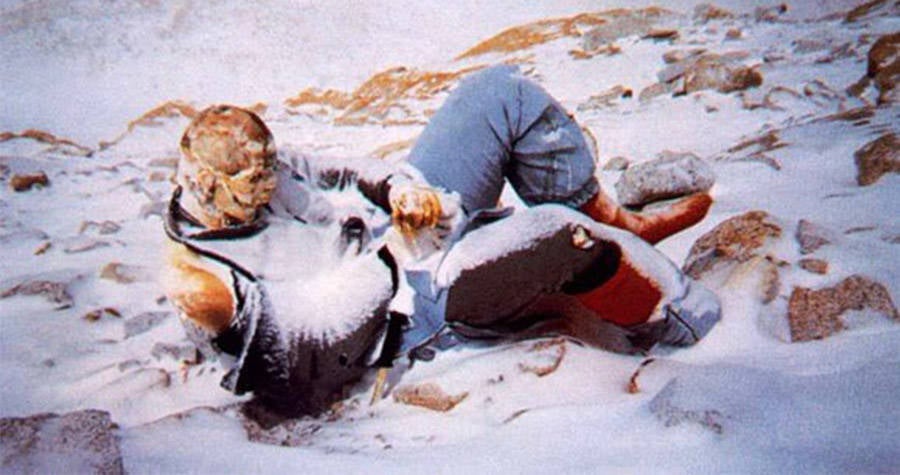

For years following her death, Hannelore Schmatz’s mummified corpse, identifiable by the backpack pushed against it, would be a gruesome warning for other mountaineers attempting the same feat that killed her.

An Experienced Climber

DWHannelore Schmatz and her husband Gerhard were avid mountaineers.

Only the most experienced climbers in the world dare to brave the life-threatening conditions that come with the ascent to the summit of Everest. Hannelore Schmatz and her husband Gerhard Schmatz were a pair of experienced mountaineers who had traveled to reach the world’s most indomitable mountain tops.

In May 1973, Hannelore and her husband returned from a successful expedition to the top of Manaslu, the eighth mountain top in the world standing at 26,781 feet above sea level, in Kathmandu. Not skipping a beat, they soon decided on what their next ambitious climb would be.

For reasons unknown, the husband and wife decided it was time to conquer the highest mountain in the world, Mount Everest. They submitted their request to the Nepalese government for a permit to climb Earth’s deadliest peak and began their strenuous preparations.

The pair climbed a mountain top each year since to increase their ability to adjust to high altitudes. As the years passed, the mountains they climbed got higher. After another successful climb to Lhotse, which is the fourth highest mountain top in the world, in June 1977, they finally got word that their request for Mount Everest had been approved.

Hannelore, who her husband noted as “a genius when it came to sourcing and transporting expedition material,” oversaw the technical and logistical preparations of their Everest hike.

During the 1970s, it was still difficult to find adequate climbing gear in Kathmandu so whatever equipment they were going to use for their three-month expedition to Everest’s summit needed to be shipped from Europe to Kathmandu.

Hannelore Schmatz booked a warehouse in Nepal to store their equipment which weighed several tons in total. In addition to equipment, they also needed to assemble their expedition team. Besides Hannelore and Gerhard Schmatz, there were six other experienced high-altitude climbers that joined them on Everest.

Among them were New Zealander Nick Banks, Swiss Hans von Känel, American Ray Genet — an expert mountaineer who the Schmatzs had conducted expeditions with before — and fellow German climbers Tilman Fischbach, Günter fights, and Hermann Warth. Hannelore was the only woman in the group.

In July 1979, everything was prepared and ready to go, and the group of eight began their trek along with five sherpas — local Himalayan mountain guides — to help lead the way.

Summiting Mount Everest

Göran Höglund/FlickrHannelore and her husband received approval to climb mount Everest two years before their perilous hike.

During the climb, the group hiked at an altitude of about 24,606 feet above the ground, a level of altitude referred to as “the yellow band.”

They then traversed the Geneva Spur in order to reach the camp at the South Col which is a sharp-edged mountain point ridge at the lowest point between Lhotse to Everest at an altitude of 26,200 feet above ground. The group decided to set up their last high camp at the South Col on Sept. 24, 1979.

But a several-day blizzard forces the entire camp to descend back to down the Camp III base camp. Finally, they try again to get back to the South Col point, this time splitting into large groups of two. Husband and wife are divided — Hannelore Schmatz is in one group with other climbers and two sherpas, while the rest are with her husband in the other.

Gerhard’s group makes the climb back to the South Col first and arrives after a three-day climb before stopping to set up camp for the night.

Reaching the South Col point meant that the group — which had been traveling the harsh mountain-scape in groups of three — were about to embark on the final phase of their ascent toward the peak of Everest.

As Hannelore Schmatz’s group was still making their way back to the South Col, Gerhard’s group continued their hike toward Everest’s peak early morning on Oct. 1, 1979.

Gerhard’s group reached the south summit of Mount Everest at about 2 p.m., and Gerhard Schmatz becomes the oldest person to summit the world’s highest mountain top at 50 years old. While the group celebrates, Gerhard notes the hazardous conditions from the southern summit to the peak, describing the team’s difficulties on his website:

“Due to the steepness and the bad snow conditions, the kicks break out again and again. The snow is too soft to reach reasonably reliable levels and too deep to find ice for the crampons. How fatal that is, can then be measured, if you know that this place is probably one of the most dizzying in the world.”

Gerhard’s group quickly makes their way back down, encountering the same difficulties they had during their climb.

When they arrive safely back at the South Col camp at 7 p.m. that night, his wife’s group — arriving there about the same time Gerhard had reached Everest’s peak — had already set up camp to get ready for Hannelore’s group’s own ascent to the summit.

Gerhard and his group members warn Hannelore and the others about the bad snow and ice conditions, and try to persuade them not to go. But Hannelore was “indignant,” her husband described, wanting to conquer the great mountain, too.

Hannelore Schmatz’s Tragic Death

Maurus Loeffel/FlickrHannelore Schmatz was the first woman to die on Everest.

Hannelore Schmatz and her group began their climb from the South Col to reach Mount Everest’s summit at around 5 AM. While Hannelore made her way toward the top, her husband, Gerhard, made the descent back down to the base of Camp III as weather conditions began to rapidly deteriorate.

At about 6 p.m., Gerhard receives news over the expedition’s walkie talkie communications that his wife has made it to the summit with the rest of the group. Hannelore Schmatz was the fourth woman mountaineer in the world to reach Everest’s peak.

However, Hannelore’s journey back down was riddled with danger. According to the surviving group members, Hannelore and the American climber Ray Genet — both strong climbers — became too exhausted to continue. They wanted to stop and set up a bivouac camp (a sheltered outcropping) before continuing their descent.

Sherpas Sungdare and Ang Jangbu, who were with Hannelore and Genet, warned against the climbers’ decision. They were in the middle of the so-called Death Zone, where conditions are so dangerous that climbers are most vulnerable to catch death there. The sherpas advised the climbers to forge on so that they could make it back to the base camp further down the mountain.

But Genet had reached his breaking point and stayed, leading to his death from hypothermia.

Shaken by the loss of their comrade, Hannelore and the two other sherpas decide to continue their trek down. But it was too late — Hannelore’s body had begun to succumb to the devastating climate. According to the sherpa who was with her, her last words were “Water, water,” as she sat down to rest herself. She died there, rested against her backpack.

After Hannelore Schmatz’s death, one of the sherpas had stayed with her body, resulting in the loss of a finger and some toes to frostbite.

Hannelore Schmatz was the first woman and the first German to die on Everest’s slopes.

Schmatz’s Corpse Serves As A Horrifying Marker For Others

YouTubeThe body of Hannelore Schmatz greeted climbers for years following her death.

Following her tragic death on Mount Everest at age 39, her husband Gerhard wrote, “Nevertheless, the team came home. But I alone without my beloved Hannelore.”

Hannelore’s corpse stayed at the very spot where she drew her last breathe, horrifically mummified by the extreme cold and snow right on the path many other Everest climbers would hike.

Her death gained notoriety among climbers because of the condition of her body, frozen in place for climbers to see along the mountain’s southern route.

Still wearing her climbing gear and clothing, her eyes remained open and her hair fluttered in the wind. Other climbers began referring to her seemingly peacefully posed body as the “German Woman.”

Norwegian mountaineer and expedition leader Arne Næss, Jr., who successfully summited Everest in 1985, described his encounter with her corpse:

I can’t escape the sinister guard. Approximately 100 meters above Camp IV she sits leaning against her pack, as if taking a short break. A woman with her eyes wide open and her hair waving in each gust of wind. It’s the corpse of Hannelore Schmatz, the wife of the leader of a 1979 German expedition. She summited, but died descending. Yet it feels as if she follows me with her eyes as I pass by. Her presence reminds me that we are here on the conditions of the mountain.

A sherpa and Nepalese police inspector tried to recover her body in 1984, but both men fell to their deaths. Since that attempt, the mountain eventually took Hannelore Schmatz. A gust of wind pushed her body and it tumbled over the side of the Kangshung Face where no one would see it again, lost forever to the elements.

Her Legacy In Everest’s Death Zone

Dave Hahn/Getty ImagesGeorge Mallory as he was found in 1999.

Schmatz’s corpse, until it disappeared, was part of the Death Zone, where ultra-thin oxygen levels rob climbers’ ability to breathe at 24,000 feet. Some 150 bodies inhabit Mount Everest, many of them in the so-called Death Zone.

Despite the snow and ice, Everest remains mostly dry in terms of relative humidity. The bodies are remarkably preserved and serve as warnings to anyone who attempts something foolish. The most famous of these bodies — besides Hannelore’s — is George Mallory, who tried unsuccessfully to reach the summit in 1924. Climbers found his body in 1999, 75 years later.

An estimated 280 people have died on Everest over the years. Until 2007, one out of every ten people who dared to climb the world’s highest peak didn’t live to tell the tale. The death rate actually increased and worsened since 2007 because of more frequent trips to the top.

One common cause of death on Mount Everest is fatigue. Climbers are simply too exhausted, either from the strain, lack of oxygen, or expending too much energy to continue back down the mountain once reaching the top. The tiredness leads to lack of coordination, confusion, and incoherence. The brain may bleed from the inside, which makes the situation worse.

Exhaustion and perhaps confusion led to Hannelore Schmatz’s death. It made more sense to head to base camp, yet somehow the experienced climber felt as if taking a break was the wiser course of action. In the end, in the Death Zone above 24,000 feet, the mountain always wins if you’re too weak to continue.

After reading about Hannelore Schmatz, learn about Beck Weathers and his incredible Mount Everest survival story. Then learn about Rob Hall, who proved that it doesn’t matter how experienced you are, Everest is always a deadly climb.