When the "Hiroshima Maidens" disfigured by the atomic bombing thought their lives were over, Japan and the U.S. united to give them a second chance.

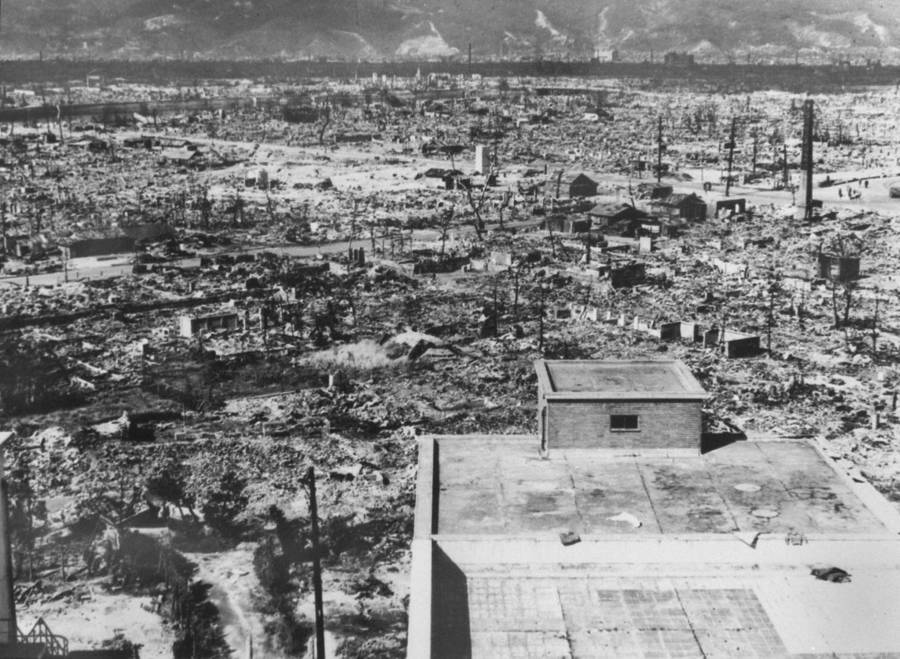

AFP/AFP/Getty ImagesHiroshima lies in ruins soon after the atomic bombing.

On Aug. 6, 1945, the U.S. military dropped history’s first deployed atomic bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima. As the crew of the plane that had just dropped the bomb watched this new weapon make most of a city and its inhabitants disappear, co-pilot Robert Lewis wrote the following words in his log: “My God, what have we done?”

Estimates of how many people that bomb killed range between 70,000 to 200,000, while countless others were permanently maimed by the blast or disfigured by burns. And even those who survived the attack — called hibakusha in Japanese — suffered long-term health effects (including abnormally high rates of cancer and birth defects) due to the lingering radiation of the nuclear bomb.

The long-lasting psychological and social effects of the bomb were particularly dreadful for women, whose prospects for marriage — and the financial stability it afforded women in the 1940s — were dashed when they were left disfigured by the bomb.

Shunned by society, a small group of these women banded together over their shared experiences. Many of them were just school girls when the bomb was dropped and as young adults were now missing eyes and noses and had burns covering huge swaths of their bodies.

The Hiroshima Maidens Come Together

U.S. National Archives and Records AdministrationA survivor of the Hiroshima bomb with the pattern of her kimono burned into her skin.

The women soon captured the attention of a Methodist minister named Kiyoshi Tanimoto who had survived the blast himself. He began fundraising and trying to secure a better future for the women via not only cosmetic surgery for their appearances but also reconstructive surgery to improve functionality in their hands on which the fingers had often been fused together by scar tissue.

The fundraising process was laborious and took nearly two years. Tanimoto enlisted American journalist and editor Norman Cousins to help and in 1953 they began what Cousins called the “Hiroshima Maidens” project. They sought donations from nonprofit organizations and the general public as well as reached out to numerous hospitals seeking donated services.

Some 30,000 people donated money to pay for the women’s travel to the United States because plastic surgery was not yet an established practice in Japan. The staff at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York was moved by photographs of the women and volunteered to provide free surgeries and hospital beds.

In The Media Spotlight

Bettmann/Getty ImagesKiyoshi Tanimoto sits with one of the Hiroshima Maidens, Shigeko Niimoto, after her arrival in New York for surgery. May 9, 1955.

The doctors performed 140 surgeries over the course of 18 months. Before and during this process, the Maidens became a media sensation. National newspapers highlighted their courage and jumped at the chance to tell a story about the atomic bomb in which Americans were viewed as heroes.

In May 1955, before their surgeries were complete, some of the Hiroshima Maidens appeared on the NBC television program This Is Your Life, an early reality show in which unwitting guests were surprised on camera by important people from their lives. An early episode featured none other than Kiyoshi Tanimoto.

The host surprised Tanimoto by bringing his wife and children into the studio, easing into the more surprising guests to come which included two Hiroshima Maidens. They were, however, hidden behind a screen and shown only in profile “to avoid causing them any embarrassment.”

Most shockingly, the show also brought Tanimoto face-to-face with pilot Robert Lewis, who stood there stiffly while awkwardly stammering through the “What have we done?” anecdote.

Despite this ethically-questionable ratings grab, the show framed this episode as a fundraising effort focused on the Hiroshima Maidens and encouraged viewers to mail in donations.

American Guilt

Los Angeles Public LibrarySome of the Hiroshima Maidens pose for a group photo after their surgeries. 1956.

All in all, the Hiroshima Maidens and the media attention they received reflect attempts by the American public to deal with their government’s decision to drop the atomic bombs. Polling data show that most Americans were initially relieved that the war was over and supported the bombing decision immediately after the bombs were dropped but developed some doubts later on.

Nevertheless, as exemplified by This Is Your Life, media treatments of the Hiroshima Maidens’ journey and recovery in America are characterized by a lack of acknowledgment of American culpability in the bombing. The Maidens in the episode state that they are “happy to be in America and thank the United States” — with no mention of the fact that the U.S. dropped the bomb in the first place.

Of course, the Maidens were indeed grateful for their treatment in the U.S. Many of them were able to lead relatively normal lives following their surgeries. Some continued giving sporadic interviews into the 1990s and praising the doctors who had changed their lives forever.

Next, see some of the most devastating photos of the Hiroshima aftermath. Then, take a look at the Hiroshima shadows of bombing victims that were burned into the ground and remained there long after the explosion.