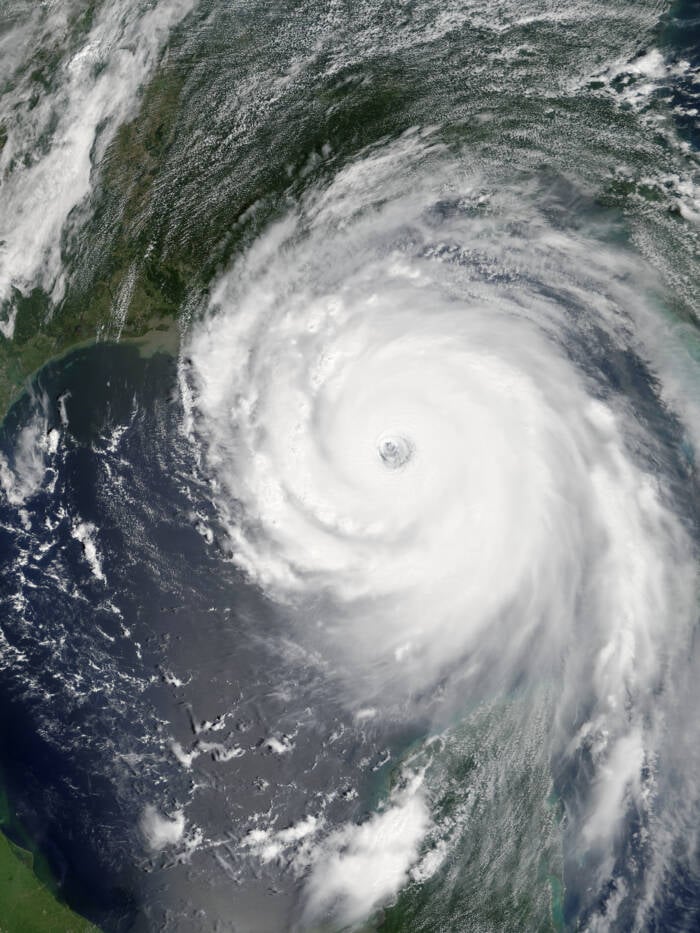

After striking the Gulf Coast of the United States in August 2005, Hurricane Katrina caused 1,392 deaths and an estimated $125 billion in damage.

Wikimedia CommonsA U.S. Coast Guard officer looking for Hurricane Katrina survivors amidst the flooding and damage in New Orleans.

In late August 2005, Hurricane Katrina swept over the Gulf Coast, tearing through communities in Louisiana, Alabama, Mississippi, and Florida. The devastating storm caused around $125 billion in damage and 1,392 deaths, and the catastrophe left hundreds of thousands of people homeless.

To make matters worse, the emergency response to the crisis was badly bungled, and the post-storm recovery had some unexpected effects on the Gulf Coast region that can still be felt even two decades later.

As one of the costliest disasters in American history, Hurricane Katrina revealed that many local, state, and federal authorities were sorely unprepared for a catastrophe of this scale, especially in New Orleans. Years after the storm, as the battered Louisiana city and its surroundings have worked to rebuild, it’s clear that some vulnerabilities still remain.

The Damage Of Hurricane Katrina Unfolds

Hurricane Katrina began as a tropical depression over the Bahamas on August 23, 2005, according to the National Weather Service. Two days later, it made initial landfall in Florida as a Category 1 hurricane. But as the storm moved over the warm waters of the Gulf of Mexico, it rapidly intensified.

By August 28th, Katrina had grown into a massive Category 5 hurricane with peak sustained winds of 175 miles per hour, and it had also become one of the strongest hurricanes that had ever been recorded in the Gulf of Mexico. The storm's eye stretched 30 miles wide, while hurricane-force winds extended about 120 miles outward from the center.

Storm surge predictions reached catastrophic levels, with forecasters warning of surges up to 28 feet along the Mississippi River.

Wikimedia CommonsA mobile home in Davie, Florida that was left severely damaged by Hurricane Katrina.

As Hurricane Katrina approached the Gulf Coast, it weakened slightly, but remained an extremely dangerous Category 3 hurricane at landfall — this time striking near Buras-Triumph, Louisiana, at about 6:10 a.m. on August 29, 2005. By 8 a.m., the storm eye's had passed through New Orleans, and the city would soon be subjected to some of the storm's worst effects.

Power quickly failed in New Orleans, making it difficult to record on-the-ground measurements of rainfall and wind velocity. Considering that a Category 3 storm has winds of 111-129 miles per hour and a Category 2 storm has winds of 96-110 miles per hour, even the low estimates were terrifying.

The storm dropped 15 inches of rain on parts of Louisiana, an amount nearly equal to the average annual rainfall in Montana. Much of the rain fell on coastal wetlands and over lakes, notably including Lake Pontchartrain. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which had been responsible for strengthening the levees around the lake, had stalled work on the project leading up to Hurricane Katrina, and many critics believed that there was inadequate funding for all the repairs and restoration that needed to be done.

It was a recipe for disaster — and disaster was what happened.

In The Aftermath Of The Storm, New Orleans Was Hit Even Worse

The destruction wrought by Hurricane Katrina was unprecedented. The storm surge flooding, which reached heights of 25 to 28 feet along the Mississippi coast, completely devastated coastal communities. In Mississippi, cities like Pass Christian and Bay St. Louis were nearly wiped off the map, with many destroyed buildings essentially reduced to rubble.

New Orleans, meanwhile, resembled a wet, tropical Stalingrad in some places. While the city initially appeared to have weathered the storm relatively well, the real disaster began after Katrina passed through. The storm surge and rainfall had completely overwhelmed the city's levee system, causing multiple breaches that led to catastrophic flooding. Around 80 percent of New Orleans was left under floodwaters, with some areas experiencing flooding depths of more than 15 feet.

Wikimedia CommonsNew Orleans, still flooded weeks after levees failed in the wake of Hurricane Katrina.

Entire neighborhoods were reduced to waterlogged rubble, with some structures swept away when the water had picked up momentum.

Meanwhile, oil barrels had also tipped into the water, coating many surfaces with a sticky, toxic residue. Bodies were left floating in the floodwaters, buried under smashed buildings, and sometimes even lying in the streets.

The recovery of some Hurricane Katrina victims was so slow that many of the bodies were decomposed or damaged to the point that the remains needed to be identified through dental records.

Journalists covering the storm, temporarily stirred to action, put a great deal of pressure on the local, state, and federal government. Officials faced embarrassing questions about nearly every aspect of the emergency management, from the budget cuts that left the city vulnerable to the competence of various political appointees managing the recovery.

The economic losses from Hurricane Katrina were staggering. Total damage estimates reached $125 billion in 2005 dollars, making it the costliest hurricane in U.S. history. It destroyed or severely damaged over 300,000 homes and displaced as many as 1.5 million people from the Gulf Coast. In New Orleans alone, about 134,000 housing units were damaged or destroyed.

But these were not the only losses caused by the storm.

The Human Cost Of Hurricane Katrina

It was later determined that Hurricane Katrina caused the deaths of 1,392 people. (It was previously estimated that there were 1,833 deaths, but this number was later adjusted by the National Hurricane Center.)

Many of the deaths occurred in Louisiana, where some victims drowned in the floodwaters that followed the levee failures. According to a report from the Louisiana Department of Health, many of those deaths occurred among elderly and disabled residents who could not evacuate.

Healthcare workers tried to save as many people as they could, while often putting their own lives at risk in the process. Mitch Handrich, a registered nurse manager at Charity Hospital in New Orleans, said, "It's like being in a Third World country. We're trying to work without power. Everyone knows we're all in this together. We're just trying to stay alive."

Wikimedia CommonsA photo showing the massive flooding damage in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina.

Beyond the fatalities, Hurricane Katrina displaced more people than any other catastrophe since the Great Depression. New Orleans' Superdome provided temporary shelter to 30,000 people in deplorable conditions.

The Ernest N. Morial Convention Center also served as an unofficial shelter for another 25,000 people, despite having no proper supplies, security, or sanitation facilities for evacuees. Of course, with so many people left without homes, the road to recovery was long and difficult — and given the emergency response, people weren't exactly optimistic.

Emergency Response Failures Highlighted Flaws At All Levels Of Government

The botched emergency response to Hurricane Katrina revealed critical failures across the local, state, and federal government, including a lack of preparation for a disaster of this scale, a slow and uncoordinated response after the catastrophe, indecision regarding the best paths forward for rebuilding, supply failures, and communication breakdowns.

Despite 56 hours of advance warning, for instance, evacuation efforts were inadequate, particularly for the city's most vulnerable populations. Though about 80 percent of the city's population got out before the storm, an estimated 100,000 people remained in New Orleans when the storm struck. Many of these citizens simply lacked the resources to evacuate.

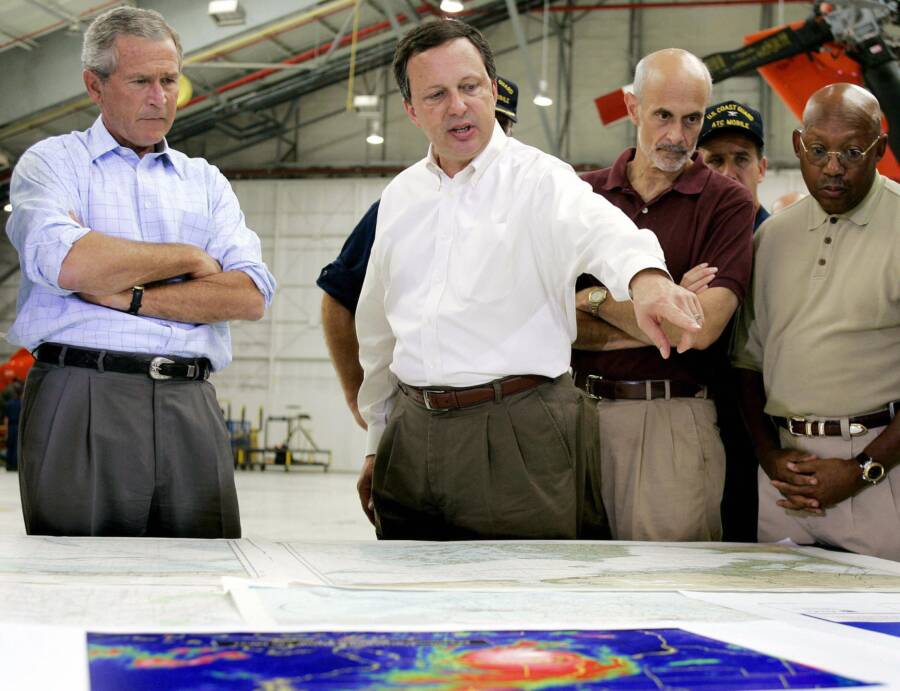

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) faced particularly severe criticism for its slow response after the storm. Then-FEMA Director Michael Brown, who had virtually no experience in emergency management, became a symbol of federal incompetence after President George W. Bush infamously praised Brown's work on the Gulf Coast.

CNNPresident George W. Bush and former FEMA Director Michael Brown.

"Brownie," the president said, "you're doing a heck of a job."

Just 10 days later, Brown resigned from the position.

A decade later, Brown would defend his actions in a piece for Politico, entitled "Stop Blaming Me for Hurricane Katrina":

"Had the mayor and governor fulfilled their responsibilities as elected leaders of their city and state, most if not all of the people crying for help in front of national television cameras would not have been there. They would have been in other locales, safe and secure.

But the blame was not placed on those responsible. The blame was placed on me—the one person who had no authority to do anything at that point except get out the checkbook and start paying the Department of Defense to evacuate people from that hellhole to a place of safety. And that is exactly what I did."

Communication failures also plagued the response effort. Different agencies used incompatible radio systems, preventing proper coordination between federal, state, and local responders. The 911 system was overwhelmed and eventually failed, leaving many residents simply unable to call for help.

Wikimedia CommonsSoldiers patrolling New Orleans in September 2005, amidst the damage left behind by Hurricane Katrina.

Search and rescue operations, while ultimately successful in saving tens of thousands of lives, were initially hampered by poor communication and resource shortages. Military assistance was delayed due to bureaucratic procedures and concerns about the Posse Comitatus Act, which limits military involvement in domestic law enforcement and civilian laws.

The U.S. Coast Guard, on the other hand, proved to be much more effective in responding to the disaster, rescuing over 33,500 people.

But even after the initial search and rescue operations, the work was not done. It was clear that recovery would be a long road ahead.

The Long-Term Aftermath And Recovery From Hurricane Katrina's Damage

The recovery from Hurricane Katrina proved to be a contentious, heavily politicized struggle that highlighted existing social and economic inequalities.

As NBC News reported at the time, the Bush White House's $51.8 billion hurricane relief bill may have had strong bipartisan support, but there was far less agreement among leaders about what to do with the money.

Various contractors, advisers, and, unfortunately, scammers swung into action to sweep up as much money as they could before it could help the people most affected by the storm. A New York Times report from the following June would highlight just how much fraud there was.

Meanwhile, New Orleans homeowners struggled to get insurance to cover the damage from the storm. After all, most insurance policies don't cover flood damage, and the floodwaters tended to wash away any damage that could be provably caused by the wind. To make things even more complicated, homeowners could pursue grants via Louisiana's Road Home program, but the grants were based on either the pre-hurricane value of the homes or the probable cost of rebuilding, whichever was a smaller amount.

A group of homeowners later sued the federal government and the State of Louisiana for discrimination, arguing that the program was set up so that a person who lived in a poor neighborhood would often receive a much smaller grant than a person who lived in a well-off neighborhood.

Wikimedia CommonsDebris from Hurricane Katrina, scattered across a home's front lawn.

Though there were disaster loans available via the Small Business Administration, which were meant to help both businesses and individual people who had suffered losses from Katrina that weren't covered by insurance, the process was highly mismanaged and many eligible business owners reported being rejected for a much-needed loan.

Retired and elderly people struggled mightily to get aid, grappling not only with complicated bureaucratic battles, but also a lack of supportive evacuation processes and accessible systems for older adults. And as many impoverished survivors were stuck in shelters, they naturally had difficulty tracking down and successfully filling out loan applications.

All of this sounds bad, but it could have been worse. Then-House Speaker Dennis Hastert publicly questioned the use of federal assistance to rebuild the low-lying city, saying, "It looks like a lot of that place could be bulldozed."

Keep in mind that by 2010, New Orleans had only recovered 78 percent of its pre-storm population, partly due to all the hoops people had to hop through to get the help they needed to rebuild their lives in the city.

Rebuilding efforts, meanwhile, were complicated by debates over which areas should be rebuilt and how to make those neighborhoods more resilient in preparation for future storms. The Road Home program ultimately distributed $9.6 billion to help homeowners rebuild or relocate, but it also faced criticism for delays, bureaucratic complications, and formulas that some argued discriminated against minority homeowners.

Lessons Learned And A Lasting Impact

Hurricane Katrina revealed many issues with the way the United States approaches disaster preparedness and inspired many to seek out a better way to respond to future catastrophes. The Stafford Act was amended to improve federal disaster response capabilities, particularly with helping evacuees who had pets, and FEMA underwent significant reforms.

The Post-Katrina Emergency Management Reform Act of 2006 clarified FEMA's authority while establishing new requirements for disaster planning — although, as of 2025, with President Donald Trump's calls to eliminate FEMA, America's preparedness for future disasters is uncertain.

Many previous administrations tried to improve FEMA, learning from the agency's past failures. The Trump administration, on the other hand, seems to think that scrapping it and starting over is the better approach.

"The president and I have had many, many discussions about this agency," explained Department of Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem, according to NPR. "I want to be very clear. The President wants it eliminated as it currently exists. He wants a new agency."

One piece of good news for New Orleans is that the levee and storm protection network has been significantly upgraded since 2005, and it's already helped to defend the city during more recent storms. However, officials also caution that the storms themselves have been changing amidst the ongoing climate crisis, sometimes developing much quicker than they did in the past and striking with far less notice.

Wikimedia CommonsA helicopter seen hovering above the floodwaters after Hurricane Katrina.

It's also worth noting that Hurricane Katrina still has an impact on day-to-day life in the city, even many years after the storm. Education systems were completely restructured in New Orleans after Katrina, with the traditional public school system largely replaced by charter schools.

Some of these private schools in Louisiana teach what is known as "Accelerated Christian Education (ACE)." Children in these schools are exposed to intensive religious instruction in every subject, not just religion-specific classes. English students are likely to be given examples of interrogative statements like these: "Do you know Jesus as your personal Saviour? Can you ever praise Him enough?"

In science, The Washington Post reported, the curriculum really takes a shocking turn. Some ACE students in Louisiana have been taught that the Loch Ness Monster is probably real, and that this might disprove evolution.

So, while New Orleans has rebuilt much of its infrastructure and economy, the storm has clearly left many lasting marks on how the city operates.

Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans with all the force and finality of a war. After the storm passed and the flooding subsided, people whose loved ones were dead and lost under the rubble came out of their shelters into a world where nobody seemed to know what to do or how to help them.

Two decades later, it remains to be seen if the world ever figured it out.

After this harrowing look back at Hurricane Katrina and the severe damage that it left behind, learn about the Great Blizzard of 1888 that devastated the northeastern United States. Then, see our collection of heartwarming photos of the dogs who survived Hurricane Harvey.