Source: NASA

The name was initially meant to be a dismissal

The term “big bang” was coined live on BBC radio in 1949 by Fred Hoyle, a scientific opponent to what was then the fringe “primeval atom” hypothesis proposed by Catholic priest Georges Lemaitre. Hoyle’s equally alliterative Steady State theory had been accepted by everyone from Einstein to Hubble, but contradicting discoveries in the 1920’s had slowly started to dismantle the erstwhile pillar of astronomical thought. Hoyle dismissed “this big bang idea” since it suggested that the universe had a beginning, implying to Hoyle that there was some sort of a creator. But both his straw man and his assumption fundamentally misrepresents what the Big Bang actually proposes.

Don’t think explosion, think expansion

Source: Physics GG

Alright, so maybe “big bang” is a bad name for what actually happened, but a ton of hot stuff accelerating in all directions sure sounds like an explosion. This is not far off; there was a lot of heat and a lot of outward motion. But the Big Bang was not an explosion in space, it was the creation of space.

After a decade of arguing against it, Fred Hoyle popularized the “balloon” analogy for what actually occurred during the Big Bang. There are a lot of flaws in this analogy, but short of a few PhD’s in mathematics it’s a fairly adequate representation of the real thing. Imagine a polka-dot balloon being blown up. As more air enters into the balloon, the space between the dots gets bigger in the same way the space between galaxies does. In other words, the bigger the balloon gets, the greater the distance between the dots.

The main issue with this visual is that it’s a three-dimensional rendering of a two-dimensional example of a three-dimensional phenomena. while the dots on the balloon will stretch, due to gravity the universe’s matter will not. But to make things even more confusing, lightwaves certainly will. And finally, the balloon gives the impression that the universe is growing within an empty space, but the Big Bang was the creation of space itself. Consequently, there is no edge to the universe.

There is no “center” of the universe

Source: Regenerating Universe Theory

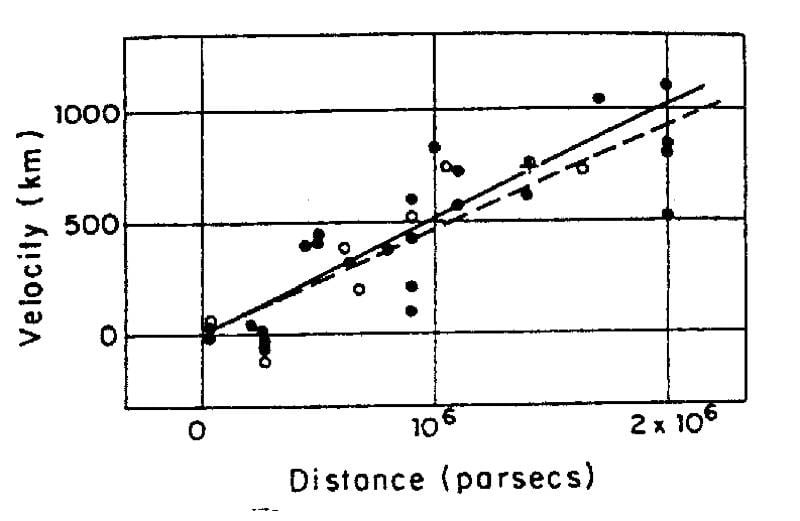

In 1929, Hubble observed that not only were many of the fuzzy nebulae among the stars actually huge, distant galaxies, but almost all of them were receding from Earth at a rate proportional to their distance. In every direction, galaxies twice as far as others were moving away twice as fast. But that would mean that the really, really distant objects would be moving faster than the speed of light, which Einstein proved impossible.

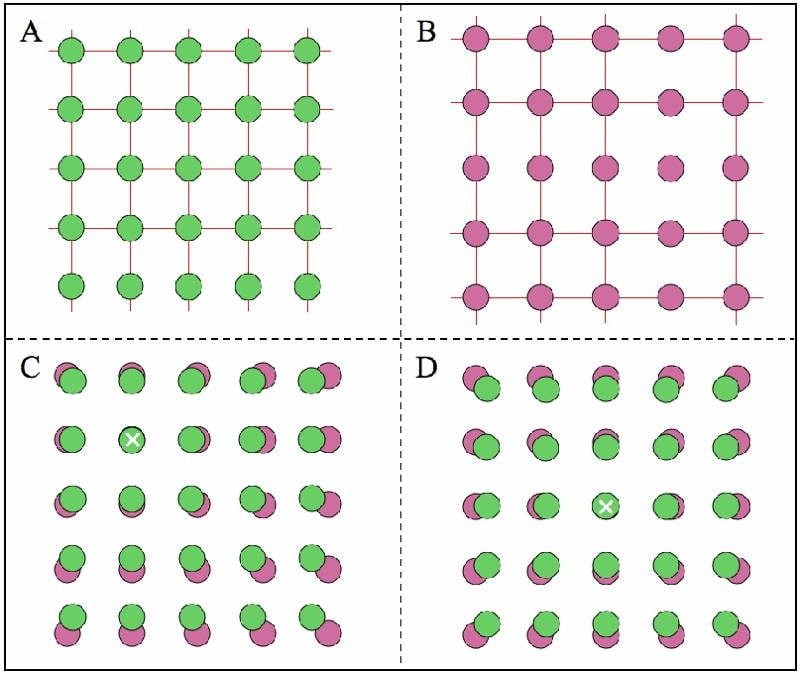

The only viable solution was that the space between objects was expanding uniformly at all points throughout the universe. That would mean that the universe had no center, but instead filled out like a TV screen when turned on. Though initially counterintuitive, the universe’s lack of center is one of the easiest ways to understand the uniformity of the expansion of space. In the following diagram, quadrant A is the state of the universe some time before that of quadrant B.

Source: University of Virginia

In Quadrants C and D, the vantage point of an observer is marked with a white x. By laying A over B and centering them both on the same vantage point, we see how it appears that that point is the center of the universe. But shift that vantage point to another star, and it becomes clear that no matter where one is looking from, he will always appear to be at the universe’s center.