Captain James Cook sailed to expand scientific knowledge — and the British Empire. He is arguably history's most accomplished navigator, but his voyages were not without controversy.

Wikimedia CommonsCaptain James Cook.

Born the son of a farmhand, James Cook did not seem destined for adventure, much less fame. However, a fateful voyage to Tahiti to measure an extremely-rare celestial event known as the Transit of Venus led him to become one of history’s greatest explorers and navigators.

Indeed, Cook sailed farther than any man of his time, was the first European to encounter New Zealand, and cemented his place in history — before being killed in Hawaii after attempting to kidnap an Indigenous leader.

James Cook, A Humble Farmer’s Ambitious Son

Wikimedia CommonsThe seaside village of Staithes where a young James Cook was apprenticed to be a shopkeeper and which introduced him to the sea. Within two years, Cook had joined the merchant marines and was on his way to a legendary career in the British navy.

James Cook was was born on Oct. 27, 1728, in the Yorkshire countryside of England. His father was a farm laborer, and in the 18th century, there was little reason to think that the son would rise much farther than his father.

The younger Cook was born at a time when social class was both highly unequal and extremely fossilized in British society: farm laborers’ sons were all but destined to become laborers themselves. Cook was fortunate enough, though, to receive a primary education.

Showing an aptitude for mathematics, this gave him the chance to apprentice himself to a shop owner in the seaside village of Staithes. Here, he was introduced to the potential of a life at sea.

Eighteen months later, Cook left to join the merchant marines. There, his aptitude for numbers paid off, and he was able to learn navigation, higher mathematics, and astronomy. His natural ability and dogged determination enabled him to become a mate in 1752.

He could have remained on this new track he was cutting for himself as he was well on his way to becoming a master of a ship in his own right, but Cook’s ambitions aimed even higher still.

And so in 1755, at age 26, James Cook joined the Royal Navy as an enlisted seaman. This was highly unorthodox for the era, as it would put him lower in rank than boys as young as 14. It was also odd since life in the Royal Navy was highly disciplined and was in many ways harder than serving in the merchant fleet.

But Cook persisted, believing that it was through the Royal Navy that he could achieve more recognition and status. It didn’t take long before he started rising through the ranks. Within a year, the Navy promoted James Cook to boatswain; within two, he became the master of his own ship.

His Early Naval Career And First Explorations

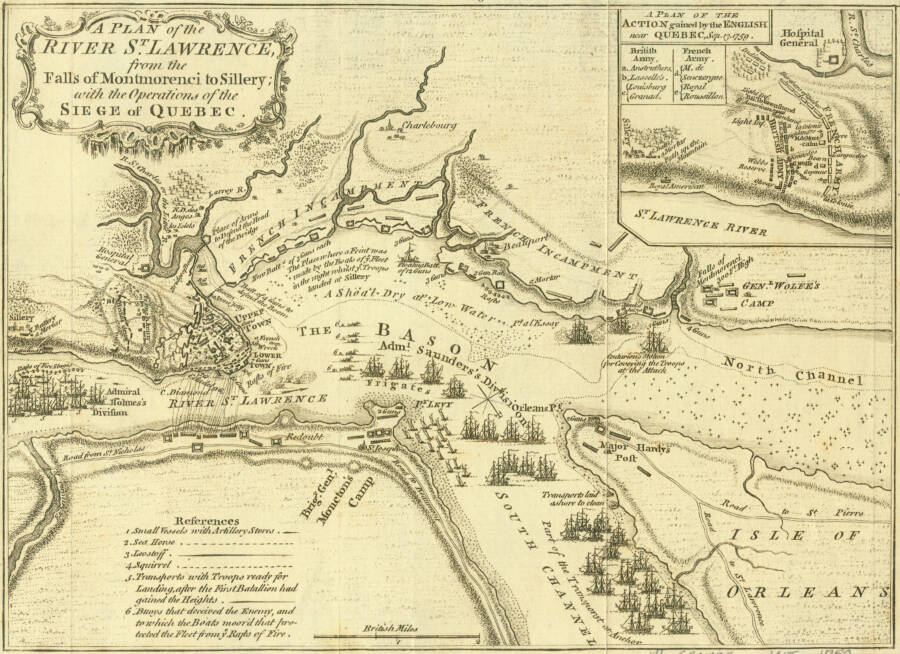

Historic Maps Collection/Princeton UniversityA map of the siege of Quebec, where James Cook distinguished himself by diligently surveying the waterways that allowed the British navy to safely sail through in force, setting the stage for the French defeat in the French and Indian War.

In 1759, Cook surveyed the French-controlled St. Lawrence Seaway in preparation for a British attack on Quebec.

His maps were of such quality that they enabled the British to sail a fleet of 200 ships up the seaway and launch an attack that eventually led to British control of French Canada.

Cook’s Navy career had been brilliant up to this point, but his personal life was less well-documented. In 1762, he married Elizabeth Batts, but history does not say much about their marriage, other than their having six children together; none of whom lived past early adulthood.

Additionally, it is likely that the couple rarely saw each other as Cook was almost always at sea.

Wikimedia Commons John Montagu, the Fourth Earl of Sandwich, who nominated James Cook to lead the expedition to Tahiti to observe the transit of Venus in 1769.

In 1766, Hugh Palliser and John Montagu, Earl of Sandwich, nominated Captain James Cook for a special assignment — and one that would forever put his mark on history.

The Royal Society in Britain was seeking a captain who could lead a voyage to Tahiti, an island in the South Pacific, to observe the transit of Venus.

This event, where an observer on Earth can see the planet Venus passing in front of the Sun, is an exceptionally rare phenomenon. Since the invention of the telescope more than 400 years ago, the transit of Venus has occurred just seven times.

But what really made this particular transit of Venus special was that in 1716, the famed British scientist Edmond Halley published a paper that showed how data collected during this event could be used to calculate the mean distance between the Sun and the Earth, a number that would finally reveal the true scale of the solar system in astronomical models.

Wikimedia CommonsPortrait of Sir Joseph Banks by Benjamin West. Banks accompanied Cook on his first voyage and his knowledge of botany helped Cook protect the crew of the Endeavour against scurvy.

Halley therefore called for scientists around the world to make observing the next two transits of Venus in 1761 and again in 1769 an international priority.

Unfortunately, the Royal Society in Britain did not have the funding to mount such an ambitious enterprise, so they appealed to the British government for help. The government quickly agreed to do so — though mostly for their own reasons, as would soon become apparent.

Captain Cook thus took command of the HMS Endeavour, a 106-foot collier converted for the long voyage. It had a crew of 94 men, including a team of scientists, chief of whom was Joseph Banks, a 25-year-old botanist who was quickly becoming a preeminent figure in scientific circles.

Just before Cook set out, the Admiralty gave him a sealed set of secret instructions that he was to open after the observation of the transit of Venus was complete.

Mapping The Transit And Searching For The Lost Continent

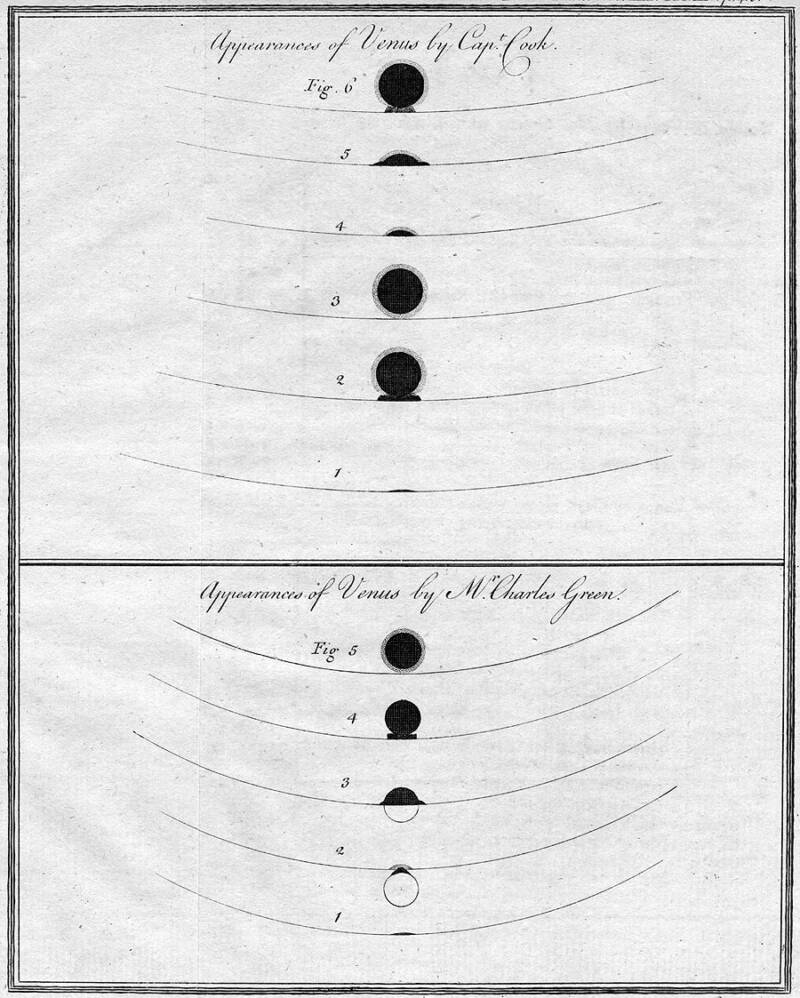

NASACaptain James Cook’s drawing of the transit of Venus on June 3, 1769.

The Endeavour set sail on Aug. 26, 1768, passing around Cape Horn in South America and entered into the vast expanse of the Pacific Ocean. Altogether, it took the Endeavour about eight months to reach Tahiti on April 13, 1769.

Banks and Cook recorded the times and positions of Venus as it ingressed and egressed the solar disk on June 3. When scientists finally calculated the distance to the Sun in 1771, it was within two to three percentage points of the current figure of about 93 million miles.

With the transit complete, it was then that Cook opened his sealed secret orders and learned why the Admiralty had agreed to finance the voyage — they wanted him to find the Terra Australis Incognita.

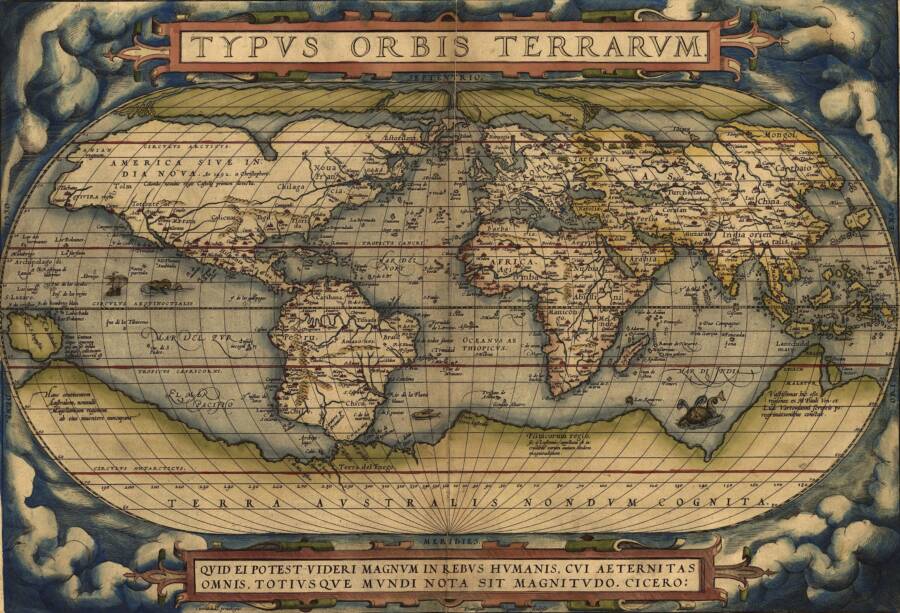

Wikimedia CommonsA map of the world from 1570, showing the hypothetical Terra Australis that was thought to exist in the southern hemisphere.

Terra Australis Incognita, Latin for the “Unknown South Land,” was a massive hypothetical southern continent postulated by Aristotle and the Greek mathematician Ptolemy to be the southern landmass that counterbalanced the northern hemisphere.

This idea of a vast, unknown continent was still believed by many in the 18th century, and with European colonization of the world ramping up, the British government was very interested in being the first to reach this undiscovered land — if it existed.

And so, James Cook directed the Endeavour to 40 degrees south latitude and sailed to the west until he reached New Zealand, which was of special interest since it was taken to be an extension of the larger Terra Australis. Cook carefully charted the coastlines of New Zealand, often making contact with the native Maori with whom there were several violent episodes.

These encounters were just the first of many such encounters to come, and it created a mixed legacy of Cook’s first voyage, so much so that in 2019 the British government expressed regret for the Maori who were killed by his men.

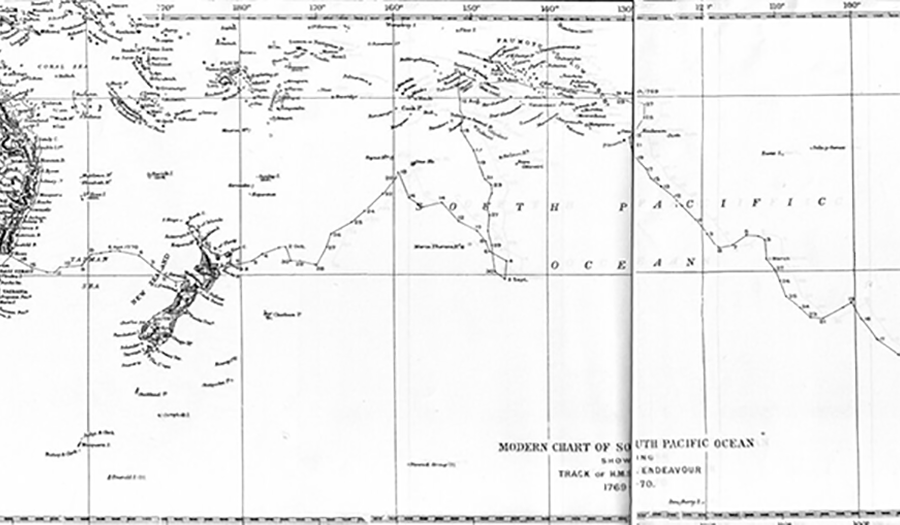

Wikimedia CommonsOne of the charts drawn by Captain James Cook as he explored the South Pacific in search of the Terra Australis.

Sailing around the entirety of New Zealand, Cook proved that it was not part of some larger continent. He then explored the unknown coast of eastern Australia, then called New Holland. The Endeavour landed at Botany Bay, so-called because of numerous new species of plants that Joseph Banks documented there.

With no sign of the lost continent, the Endeavour began its return to England after two years at sea.

James Cook’s Adventures In The Antarctic

Wikipedia

Portrait of James Cook by William Hodges, who accompanied Cook on his second voyage

Upon his return, Cook was promoted by the Admiralty to Commander. Almost immediately, another voyage was planned for him to travel as far south as possible in latitudes no ship had ever ventured in order to prove or disprove the existence of Terra Australis once and for all.

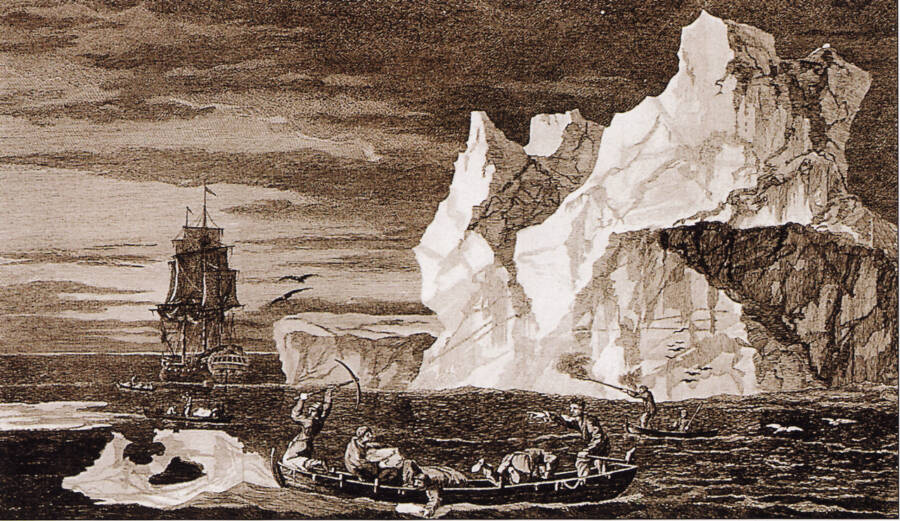

Cook requested two ships for the voyage, the HMB Resolution and the HMS Adventure. The two vessels left Plymouth, England, on July 13, 1772. Passing the Cape of Good Hope and continuing south, Cook spotted icebergs beginning in early Dec. 1772, and within a week or two, Cook recorded an “immense field of Ice” as he pushed as far as 55 degrees south latitude.

As the southern summer took hold, the pack ice receded, allowing Cook to pass the Antarctic circle for the first time on Jan. 17, 1773, becoming the first western mariner known to have done so. The men were awed by the dramatic polar seas with their towering icebergs as they inched their way through the Antarctic waters — but still, there was no sign of Terra Australis. Cook wrote:

“…[the ice] extended east and west far beyond the reach of our sight, while the southern half of the horizon was illuminated by rays of light which were reflected from the ice to a considerable height. … It was indeed my opinion that this ice extends quite to the Pole, or perhaps joins to some land to which it has been fixed since creation.”

With no sign of the unknown continent, Cook decided it was time to go back to England. He swept through the tropics again, landing at the crew’s favorite port in Tahiti as well as voyaging to remote spots such as Easter Island, whose mysterious statues awed the men of the Resolution. He also mapped numerous islands such as South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands.

What benefited Cook on this voyage was a secondary objective to test of a new invention called a chronometer, which was designed to solve one of the most significant challenges in navigation: how to fix longitude.

Wikimedia CommonsCook in Antarctica drawn by William Hodges.

The device was a reliable sea clock that was used to measure local time against Greenwich Mean Time, and by it, a mariner could calculate his position with a great deal of accuracy. Cook was probably the first explorer who could accurately know where he was at any given time.

Combined with his exceptional skill at surveying and cartography, Cook’s charts of his second voyage were so accurate that they were used into the 20th century.

His Attempts To Find The Fabled Northwest Passage

James Cook returned to England in July 1775 and was honored for his feats of exploration. He was promoted to post-captain and given a position at Greenwich Hospital that would have ensured him a lifetime income.

However, the exploration bug possessed Cook, and he set out to try to settle another puzzle of the Pacific Ocean: the location of the Northwest Passage.

For centuries, European explorers had been seeking a way to the Pacific over North America but had long been stumped, with many explorers probing from the Atlantic side dying in the attempt. Failing to find a passage from the northeastern side of the continent, the Admiralty thought that perhaps Cook could discover it by searching along the unknown northwest coast of North America.

Cook left on his third and final voyage aboard the Resolution and the Discovery in July 1776, but Cook, who was then 47, seemed to be a different man. His patience had given way to short bursts of anger, and he acted in bouts of violence against Indigenous peoples.

As reported by The Conversation, it seemed Cook had grown irritated with Indigenous groups across the Pacific for refusing to assimilate to the aspects of western culture he had introduced them to.

For instance, when he visited Tahiti, he lamented how “despite a decade of European encounters and exchanges,” he found “neither new arts nor improvements in the old, nor have they copied after us in any one thing.”

Wikimedia CommonsA painting of Kealakekua Bay by John Webber, an artist aboard James Cook’s ship.

Though Cook eventually concluded that there was no northwest passage as ice blocked the only feasible way through the Bering Strait, he did encounter a group of islands in the Pacific previously unknown to Europeans, which he named the Sandwich Islands — but which we now know as Hawaii.

There, Cook stopped to trade and resupply before departing to explore the Pacific Northwest, but he returned a year later to provision and explore the islands more thoroughly.

What happened next when Cook went ashore on Feb. 14, 1779, is the subject of intense debate.

The Death Of James Cook

The most well-known account of this day claims that after anchoring in Kealakekua Bay on the Big Island in late January, Cook found that he had arrived during a festival for the Hawaiian god Lono. In the religious processions, the Hawaiians carried crosspieces wrapped with a white cloth that bore a resemblance to a ship’s sails.

The Hawaiians considered Kealakekua Bay sacred to Lono, a fertility god. So, when the Hawaiians saw the white sails of Cook’s ships anchored in the bay during the festival to the god in question, they treated Cook and his crew as messengers of Lono, if not as living gods themselves.

This reverence didn’t last long, though, as Cook and his crew quickly took advantage of the Hawaiians’ hospitality for more than two weeks. On their earlier visit the year before, Cook’s crew traded common iron nails for sex with Hawaiian women, so it’s highly likely the crew acted in a similarly exploitive nature.

No doubt angered by the deception, the mood quickly turned against the British.

Wikimedia CommonsA depiction of the death of Captain James Cook.

After having worn out their welcome, Cook and the crew set sail on Feb. 4, 1779, hoping to carry on with more explorations. However, gales soon broke Cook’s foremast which required repair, so Cook was forced to return to Kealakekua Bay.

The situation was tense as the British returned, with the Hawaiians throwing stones at the British. Reports become contradictory here, as Cook either went ashore planning to kidnap the Hawaiian Chief Kalei’opu’u to hold as a hostage, or he went ashore to try to calm the situation down and negotiate for the return of the cutter.

In either case, once ashore, Cook and the marines found themselves greatly outnumbered by Hawaiians, and by some accounts, one or more of Cook’s party shot and killed a lower-ranking Hawaiian chief. Soon, the marines were shooting indiscriminately, and Cook was struck on the head and stabbed in the surf. He died face down in the water, along with four other sailors.

The remaining marines managed to escape to the ships and the British retaliated with skirmishes and cannons — for days by some accounts.

Meanwhile, the Hawaiians took Cook’s body, dismembered it, and put his bones into a casket. Though the British claimed this was mutilation, some Hawaiian scholars have insisted that this treatment was consistent with high funerary honors.

Cook’s lieutenant, Charles Clerke, had taken command of the Resolution and demanded that the Hawaiians return Cook’s body so they could properly bury him at sea.

Clerke led the expedition back to Britain, with Cook’s third voyage ending at the beginning of October 1780 without him.

Cook’s Legacy As An Explorer, Scientific Pioneer, And Global Imperialist

Wikimedia CommonsStatue of Captain James Cook at the Admiralty Arch in London.

Arguably, Captain James Cook filled in more blanks about the West’s picture of the globe than any other explorer before. He also demonstrated the practical application of science through his use of the chronometer.

His voyages were an altogether different affair than other explorers of the era. “The Endeavor was not only on a voyage of discovery,” said Pulitzer-Prize-winning author Tony Horwitz in his book Blue Latitudes. “It was also a laboratory for testing the latest theories and technologies, much as spaceships are today.”

At the same time, however, Cook also increased the scope of Britain’s global empire, for which he was hailed as a hero by many ever since. To others, he is seen as the harbinger of colonialism in the Pacific, and an exploiter of the human civilizations who had already been inhabiting the lands he claimed to have “discovered” for tens of thousands of years.

Like many figures in history, the reality might not be either-or, but both-at-once, and Captain James Cook’s legacy in part is the reminder that legacies are never the simple affairs we’d like them to be.

Now that you’ve read about the voyages of Captain James Cook, learn about Alexander Selkirk, the marooned British sailor who may have been the inspiration for “Robinson Crusoe.” Then, read the extraordinary tale of how Ada Blackjack outlived her all-male crew after being stranded in the Arctic for two years.