James Morison claimed that his vegetable pills could cure anything from smallpox to dysentery — and thousands of British people believed him.

In the 19th century, when medical knowledge was lacking among doctors and the undereducated public was easily deceived, scam artists and quack doctors reportedly outnumbered real ones by three to one. But one quack stood tall above the rest for the sheer brazenness of his scam: a British businessman named James Morison.

Wikimedia CommonsJames Morison in a publicity image for his fake medical college.

After falling ill in the early 1820s, Morison grew disgusted with physicians and their remedies and decided he could do better.

And so he invented a cure-all pill and fooled a shocking number of people, growing rich in the process.

Trust Morison — Not The Doctors

The exact type of illness James Morison suffered is unknown, but he described it as “thirty-five years’ inexpressible suffering.” And he believed the vegetable pills he concocted were the only thing that cured him.

Based on his own recovery, Morison determined that all ailments — including pain — were simply the result of a blood defect. He believed that vegetable laxatives could effectively purge the impurities and restore patients’ health. As far as Morison was concerned, real doctors were making it too complicated.

In 1825, Morison consolidated his ideas into a handy pill made of all-natural ingredients: Aloe, rhubarb, cream of tartar, and myrrh.

Morison declared the miracle pill would alleviate any and all health issues, from dysentery and smallpox to fevers, pimples, and even talking in one’s sleep. It would allegedly do all this through forced defecation.

His magical capsule became known as the Universal Pill, or Morison’s Pill. It came in two strengths, No. 1 and No. 2, and was promoted as medication that could be taken as often as needed. Thirty pills a day was perfectly fine —particularly for Morison’s sales.

English folklorist and author Eric Maple wrote in his 1968 book Magic, Medicine and Quackery that Morison’s miracle pills were “the most remarkable rubbish that the century had so far seen.”

To add legitimacy to his “rubbish” enterprise, James Morison dreamed up the British College of Health, with him serving as the chief “hygeist.” His new organization sounded perfectly official, and to build credibility he flooded the market with advertising, touting testimonials from patients and endorsements from others in the field of dubious medicine.

It remains unclear how many of them were legitimate, but the sick made for quick believers.

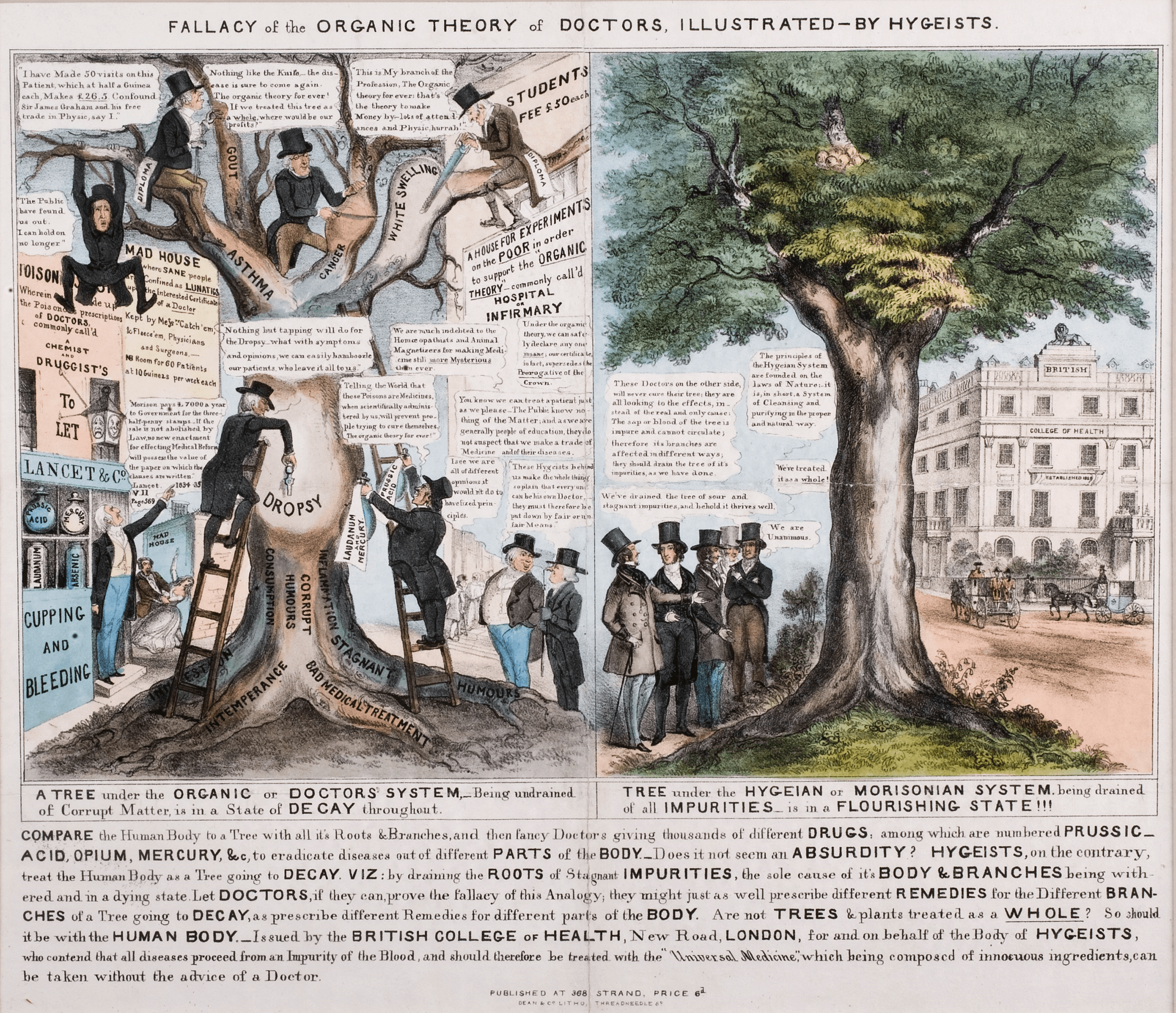

Wikimedia CommonsAn enormous ad James Morison took out touting his cure-all pills as medically safe.

Morison took out one rather remarkable ad in the busy style of the time comparing the human body to a tree and assuring the public that they could start on a regimen of his laxative pills without even speaking with their doctor:

“Are not trees and plants treated as a whole? So should it be with the human body. Issued by the British College of Health, New Road, London, for and on behalf of the Body of Hygeists, who contend that all diseases proceed from an impurity of the blood, and should therefore be treated with the “Universal Medicine,” which being composed of innocuous ingredients, can be taken without the advice of a doctor.”

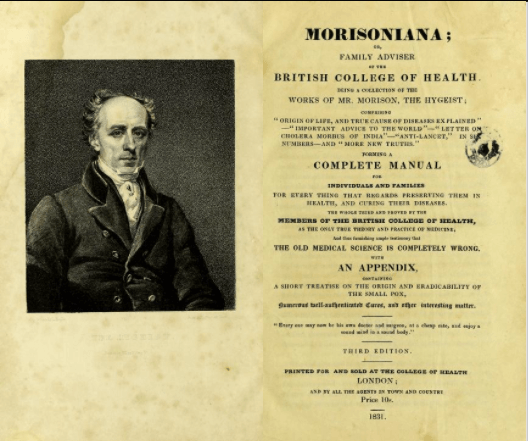

Public Domain/King’s CollegeMorison wrote and published a treatise on health to lend legitimacy to his cure.

To Morison’s credit, his laxative pills were arguably a preferable option to the then-common practice of blood-letting. “If you take too little blood, you do no good; if you take too much, you kill the patient,” he wrote in his 700-page promotional book, Morisoniana, first published in 1828 by his own, wholly invented College of Health.

“To convince the world, I am ready to take them in any doses, and for any length of time, and numbers of other persons have done the same thing, and always to their great benefit — the more they are taken, the greater is the good,” Morison declared. “Are the blood-letters ready to do the same thing, by having their blood drawn off?”

Though James Morison was right about the absurdity of blood-letting, his attacks on traditional medical practices and mission to reinvent health care did not go without criticism from the medical community.

Thomas Wakley, founding editor of the still-published medical journal, The Lancet, tried to discredit the pills’ effectiveness and the theories behind them.

Other physicians joined the campaign against Morison, warning the public that he was nothing but a fraud. But people didn’t want to hear that. They wanted quick fixes.

James Morison’s Vegetable Pills: Miracle Or Mockery?

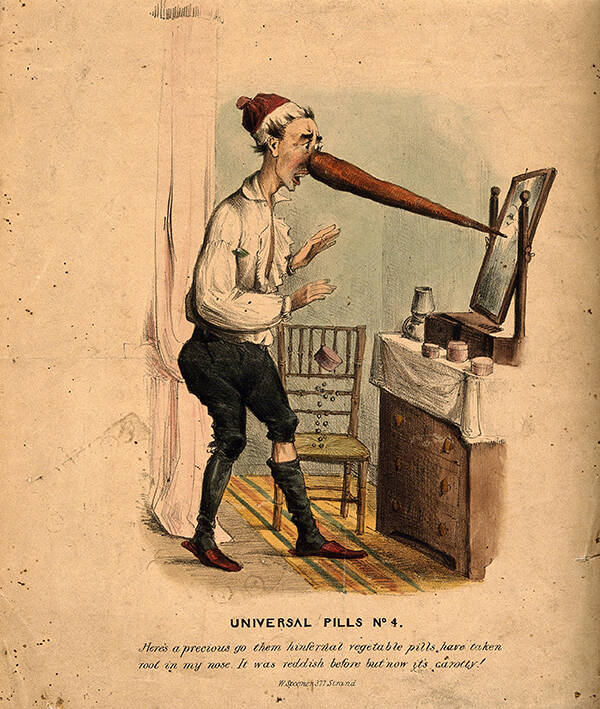

Wellcome CollectionA satirical cartoon of a horrified man discovering that as a result of taking J. Morison’s vegetable pills, his nose has turned into a carrot.

One testimonial printed in an 1832 edition of The Spectator came from a man who claimed his wife had been suffering from chest pains for 12 years and had sought the best medical advice available, with no results to show for it.

“She was induced to apply to your Pills, by which, after undergoing a regular course for a few weeks, she was entirely cured,” he stated.

Another man even claimed the pills cured his hernia. “I tried many sorts of bandages and trusses, but without effect,” he explained, but after ordering two boxes of Morison’s, “which I have taken according to instructions given, I am happy to say my rupture has not troubled me since.”

Despite the picture of perfect health Morison painted, there were a few bumps in the road for the clever quack. Namely, people started dying.

In one case, a 15-year-old girl “died in horrible distress in consequence” of taking the pills. In a more publicized 1836 incident, a Morison sales agent named Robert Salmon was convicted of manslaughter for administering a thousand pills over the course of twenty days to Captain John Mackenzie, 32, who’d been suffering from knee pains.

Desperate for any sort of relief, Mackenzie also had a doctor apply 14 leeches to his knee. A post-mortem determined the pills (not the leeches or anything else) had been the primary cause of death. He had taken seventy-two of them the day before his passing.

Twelve more deaths linked to overdoses were investigated in York a year later. Morison evaded punishment since his agents served as scapegoats — and made the prudent decision to leave England for Paris sometime around 1834.

After Morison’s flight, one of his vendors was even convicted of manslaughter after another death.

Other ads also appeared in publications mocking the good “doctor.” A recurring theme in the cartoon images was patients of Morison sprouting vegetables, tree limbs, and leaves from their body — presumably from an overdose of the vegetable laxatives.

The Surprisingly Long Half-Life Of James Morison’s Cure-All

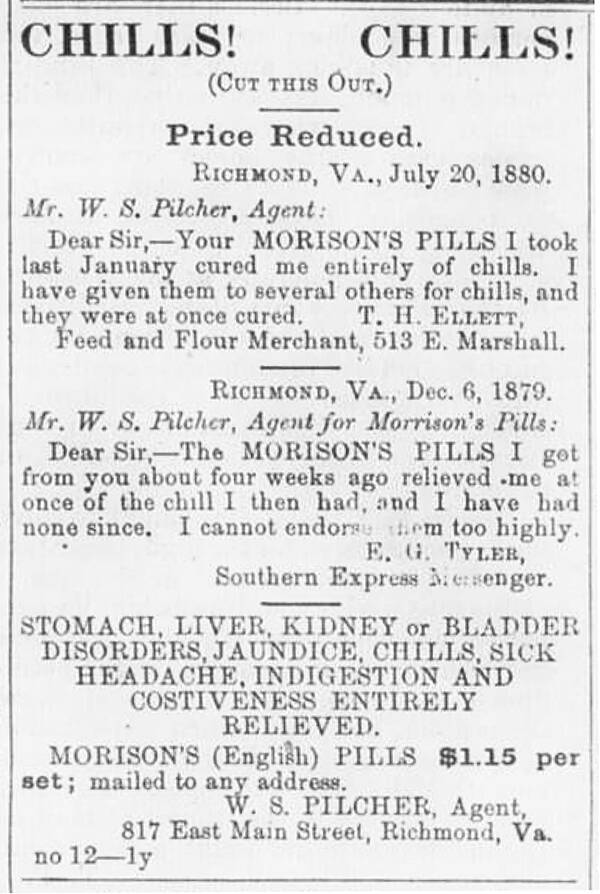

Central PresbyterianDecades after James Morison’s death, his pills continued to sell, thanks to ads like this one from November 10, 1880.

Despite the bad publicity and the potential to cause more deaths, Morison continued to push the pills — and even suggested people take more of them. He reminded the public in advertisements that his miracle pill might not work right away, but that was no reason to give up.

“To those taking Morison’s Pills we say, do not stop taking them when you feel worse, rather increase the doses,” read an ad from 1838. “You must feel worse when the medicines begins to act upon the foul acrimonious humors of the body which often have been left to fix themselves with almost fatal grasp to the intestines, and many times made stronger still, by mercurial and other hurtful poisons.”

By 1840, at the age of 70, James Morison met his own demise. No records state an overdose as the cause. However, Maple wrote that the quack doctor was about to pop a few of his own pills before death cut him off.

Whatever Morison’s ailment, he surely died with a smile on his face. His charlatanism netted him £500,000, which equates to more than £51 million today. That’s approximately $71 million.

Morison’s sons carried on the family business and even extended the empire. Hopeful patients continued to buy the pills for decades, until Britain finally put a stop to sales in 1920 and healed his particular brand of quackery.

After learning about the bizarre case of James Morison, read about America’s biggest medical quack, Henry Cotton. Then, learn about John Brinkley, the phony doctor who used goat balls as a cure-all.