Even though trailblazing mathematician Katherine Johnson helped put some of the first astronauts into space in the 1960s, she didn't get her due until decades later.

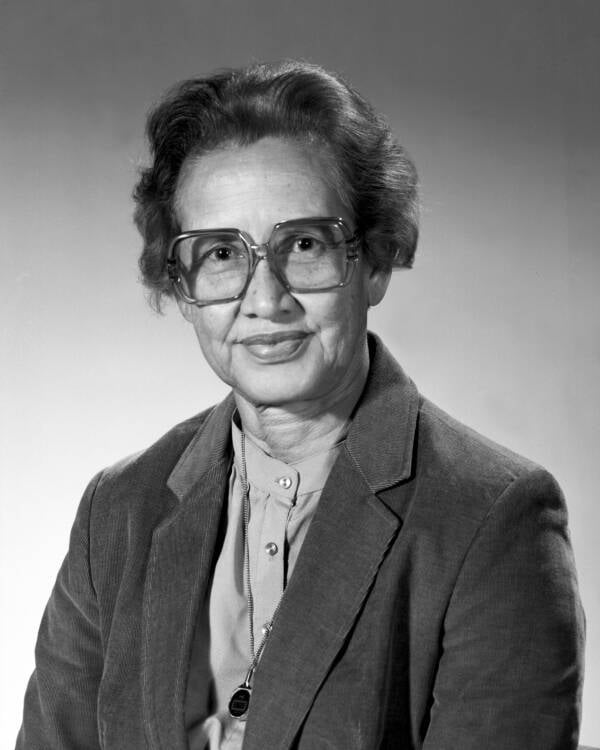

NASA/Donaldson Collection/Getty ImagesKatherine Johnson at her desk while working for NASA in 1962.

When Katherine Johnson retired from NASA in 1986, she capped off an astonishing career as one of the most invaluable “computers” in the history of the agency. Starting in the 1950s, her invaluable mathematical calculations had helped push NASA’s space exploration to untold heights. Yet, for most of her career, these accomplishments went largely ignored.

As a black female scientist in a white man’s world, Johnson worked tirelessly and often thanklessly to make calculations that put some of history’s first astronauts into space — while facing bigotry from all sides.

But in the decades following her retirement, Johnson’s legacy of peerless perseverance and intelligence gradually received the recognition it always warranted. In 2015, President Barack Obama awarded her the Presidential Medal of Freedom and her work was immortalized in the Academy Award-nominated film Hidden Figures the following year. By the time she ultimately passed away at the age of 101 in February 2020, her deserved place in history was secure.

“I Counted Everything”: Katherine Johnson’s Early Life

NASAJohnson’s complex calculations were instrumental in many of NASA’s successful space missions, including the 1969 moon landing.

Before Katherine Johnson became one of NASA’s most valuable mathematicians and earned the nickname “Human Computer,” she was born Creola Katherine Coleman on Aug. 26, 1918, in White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia.

She grew up in a modest household with three older siblings and a mother, Joylette Coleman, who was a school teacher and a father, Joshua Coleman, who was a farmer. But it was clear from an early age that Johnson was special.

“I counted everything,” she recalled near the end of her life. “I counted the steps to the road, the steps up to church, the number of dishes and silverware I washed… anything that could be counted, I did.”

This eager young counter quickly proved to be a brilliant student at school. And because the segregated school system only provided black students with classes until sixth grade in their area, her father, determined to give his gifted daughter a proper education, drove his children 120 miles every day to Institute, West Virginia, where they could continue their education.

She graduated high school by the age of 14 and immediately enrolled at West Virginia State, where she met the man who would become her early mentor: William Waldron Schieffelin Claytor, a distinguished mathematician who was only the third black person to earn a doctorate in mathematics from an American university.

At West Virginia State, Katherine Johnson’s voracious appetite for mathematics only grew. By her junior year, the budding scientist had completed every math course available at the college. Claytor had to design special classes specifically for her in order to keep her mind satiated with math.

“You’d make a good research mathematician and I’m going to see that you’re prepared,” Claytor told his star pupil. An African-American pioneer in mathematics who had been repeatedly denied opportunities and honors in the white world of academia, Claytor was upfront about the racial barriers that Johnson would face in the field as a black scientist.

“That will be your problem,” he candidly replied when she asked him about her job prospects. Claytor was right. Failing to find work after graduating cum laude with a double degree in mathematics and French in 1937, Johnson took a job as a school teacher.

NASAAs a black female scientist, Katherine Johnson broke through overwhelming race and gender barriers in order to succeed.

Unable to stay away from high-level math for long, however, she soon enrolled in the advanced mathematics graduate program at West Virginia State. Following the historic Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada U.S. Supreme Court decision in 1938, her black college was integrated with the all-white institution of West Virginia University. Katherine Johnson was one of the first three black graduate students handpicked to integrate the institutions.

But soon after she married chemistry teacher James Francis Goble in 1939, she became Katherine Goble — and became pregnant. She quickly dropped out of the graduate program to focus on motherhood and put her soon-to-be historic career on hold.

Joining NASA And Making History

Smith Collection/Gado/Getty ImagesHer incredible contributions, which were largely ignored during her time at NASA, were brought to life in the 2016 book and film Hidden Figures.

For ten years after she left graduate school, Katherine Johnson preoccupied herself with motherhood, family, and her teaching job.

But the spark of her intellectual ambition could not be stifled and, in 1952, she found out that the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) — which would become NASA a few years later — had opened its applications to black women.

NACA’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia, had only begun hiring white women mathematicians (often dubbed “computers” back then) two decades prior to relieve male engineers from having to perform exhausting manual calculations.

But a shortage of labor resources in the U.S. caused by World War II kicked open the door for job opportunities for people of color in nearly all sectors of industry, including engineering. In addition to white women, Langley was now hiring female mathematicians who were black.

Katherine Johnson began her work at NACA in 1953 in Langley’s West Area Computing unit, to which the black women mathematicians were relegated. Like all of NACA’s “computers,” Katherine Johnson and her black women colleagues — including Dorothy Vaughan and Mary Jackson — were equipped with only relatively rudimentary tools like a slide rule and graph paper — and still completed complex calculations used for NACA’s flight missions.

“I don’t have a feeling of inferiority… Never had. I’m as good as anybody, but no better.”

Two weeks into her new job, Johnson was temporarily brought in to the Flight Research Division to help calculate the aerodynamic forces on airplanes. She was the only African-American employee in the division.

“The guys all had graduate degrees in mathematics; they had forgotten all the geometry they ever knew,” Johnson said. “I still remembered mine.” Bringing her particular knowledge to the table, she was kept on at the division — where she would soon make history.

NASAIn 2017, NASA dedicated one of the buildings at the Langley Research Center to Katherine Johnson.

In 1961, she accurately calculated the numbers that helped Alan B. Shepard Jr. become the first American in space. The following year, she helped John Glenn become the first American to orbit the Earth aboard the Mercury vessel Friendship 7. And in 1969, Katherine Johnson helped determined the trajectories that would allow the Apollo 11 mission to successfully put the first human beings on the moon.

Despite these incredible accomplishments, Katherine Johnson’s significant work behind-the-scenes along with those of her black women colleagues remained largely hidden and unacknowledged.

Overcoming Barriers Of Bigotry

Wikimedia CommonsKatherine Johnson was among the first African-American female mathematicians hired as a NASA “computer.”

Like all of her black colleagues during her 33-year career with NASA, Katherine Johnson was kept segregated from her white peers, both men and women.

In later interviews, Johnson maintained that despite the racism-fueled barriers put in her way, the agency treated their African American engineers respectfully.

“NASA was a very professional organization,” Johnson told North Carolina-based publication The Observer. “They didn’t have time to be concerned about what color I was.”

Nevertheless, Katherine Johnson and her African-American colleagues were treated differently. They were assigned a separate office — including Johnson, who was placed in the mostly white and male Flight Research Division — dining facilities, and bathrooms in order to keep them separate from the white employees.

But, without realizing it, Johnson had been using the women’s restroom meant for white employees since she joined the agency — an easy mistake for a new employee to make since the white bathrooms were unmarked (unlike the black bathrooms which were still marked as such).

After she realized she had been using the bathroom for white women employees by mistake, Johnson refused to be segregated and continued to use the same bathroom. She was never reprimanded for it.

OSTPWhite House Office of Science and Technology staffers meet with Katherine Johnson after her Medal of Freedom award ceremony.

Meanwhile, Katherine G. Johnson also paved the way for women at NASA to attend the agency’s scientific briefings, which were previously regarded as for male staff only.

“Is there a law against it?” Johnson pointedly asked when she was barred from one of the agency’s briefings. Her male colleagues — confronted by the absurdity of the non-rule — let her in.

Hidden Figures

During her career at NASA, Katherine Johnson clearly did much more than make calculations. In fact, she published more than two dozen technical papers and was among the first women at the agency to ever co-author a report. And when she was making calculations, she was doing it with a near-superhuman accuracy the likes of which her colleagues had scarcely seen before.

Astronaut John Glenn, whose team made it around Earth using her numbers, regarded Johnson’s calculations as the final word for his flights — even after computers had made the same calculations.

“When he got ready to go,” Johnson recalled, “he said, ‘Call her. And if she says the computer is right, I’ll take it.'”

Yet, Johnson’s astounding work went largely unrecognized during her career.

Twentieth Century Fox Taraji P. Henson (left) portrayed Katherine Johnson alongside Janelle Monáe (right), who played her real-life colleague Mary Jackson, in Hidden Figures.

Finally, in 2016, African-American writer Margot Lee Shetterly published Hidden Figures, which recognized the work of the black women “computers” behind NASA’s accomplishments during the 1950s and 1960s.

That same year, an Academy Award-nominated film version of the same name was released starring Taraji P. Henson as Katherine Johnson. While the movie had “the spirit of authenticity,” in Shetterly’s words, not everything depicted in the film was accurate.

For starters, while Katherine Johnson’s work was indeed instrumental to the success of numerous space missions, it took an army of engineers and scientists to carry out those missions. But in the film, it appears as though only a handful of characters were responsible.

Some characters in the film were a composite of real people at the agency, like Johnson’s supposed superior Al Harrison (played by Kevin Costner). Harrison was largely based on Robert C. Gilruth, the former head of the Space Task Group at Langley.

Getty ImagesKatherine Johnson received a standing ovation at the Academy Awards when she appeared on stage with the cast of Hidden Figures.

Furthermore, Johnson was never forced to run around the NASA grounds to relieve herself in the black bathroom as portrayed in the film. In Hidden Figures, only after her superior Al Harrison (played by Kevin Costner) lets her use the nearby white facilities does she stop running around looking for a bathroom.

The film also shows Harrison’s character “breaking the rules” to allow Johnson inside the men-only briefings. But, in truth, the racist and sexist barriers enforced by NASA’s segregated bathrooms and closed briefings were broken down by Johnson herself.

The Inspiring Legacy Of Katherine Johnson

After Katherine Johnson retired from NASA in 1986, she became a public advocate for mathematics education, encouraging students to apply themselves in the sciences.

Ironically, it wasn’t until her retirement years that Johnson’s service to NASA and the country received large-scale acknowledgment — largely thanks to the release of Hidden Figures. In 2016, the year of the release, Katherine Johnson was listed as one of the 100 influential figures of the world on BBC’s “100 Women” list.

The following year, NASA dedicated a building in her honor at her former Langley stomping grounds, named the Katherine G. Johnson Computational Research Facility.

Nicholas Kamm/AFP via Getty ImagesPresident Barack Obama presents the Presidential Medal of Freedom to NASA mathematician and physicist Katherine Johnson in 2015.

But what may be her greatest accolade came two years earlier, when she received the nation’s highest civilian honor. On Nov. 24, 2015, President Barack Obama awarded Johnson the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Ultimately, on Feb. 24, 2020, Katherine Johnson died at the age of 101. She is survived by two daughters, six grandchildren, and 11 great-grandchildren — as well as a legacy of perseverance that’s rarely been equaled in modern history.

As Obama said during her medal ceremony, “In her 33 years at NASA, Katherine was a pioneer who broke the barriers of race and gender, showing generations of young people that everyone can excel in math and science, and reach for the stars.”

Now that you’ve learned about NASA’s Katherine Johnson and Hidden Figures, discover all there is to know about Harriet Tubman. Then, learn about Madam C.J. Walker, the entrepreneur who became one of American history’s first black female millionaires.