In 1954, over 5,000 prisoners in the Kengir camp rose up against the guards, forcing them to flee the grounds. And for 40 days, the inmates got a brief taste of freedom.

Library of CongressGulag prisoners, like those who started the Kengir uprising, often lived in squalid conditions.

In 1953, the prisoners at the Kengir gulag had something new — hope. The notorious Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin was dead. And Lavrentiy Beria, the head of his secret police, was named an “enemy of the state” and executed. So the Kengir inmates dared to wonder if their ordeal was ending.

Sadly, this was not the case. Stalin or no Stalin, life within the labor camp dragged on as usual. Prisoners endured brutal torture at the hands of the guards, and the administration threatened to make their lives even more miserable. By early 1954, many people in Kengir were growing restless.

Tired of waiting for their lives to get better, a group of prisoners at Kengir decided to take matters into their own hands. On May 16, 1954, about 5,000 inmates rose up against the vicious guards and administrators — and led an uprising that would last for over a month.

The Rising Tensions At The Kengir Gulag

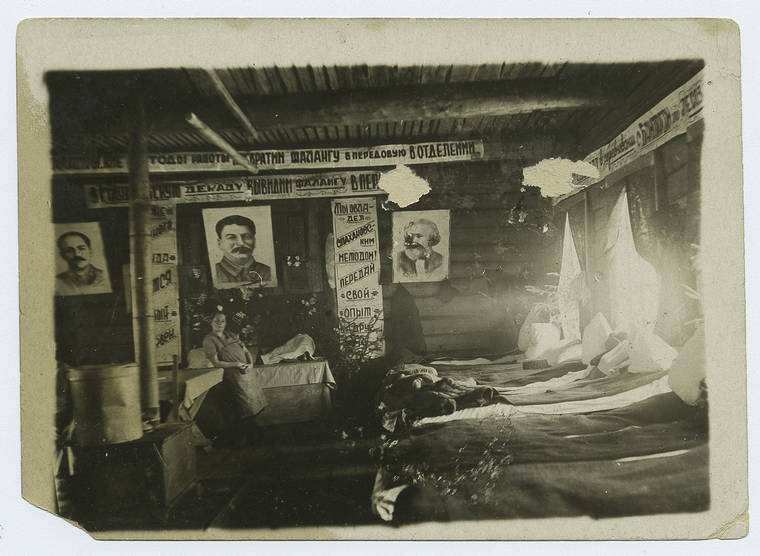

New York Public LibrarySoviet propaganda stares down at the prisoners living in a gulag.

Gulag camps like Kengir had been a facet of Soviet life since the 1920s. At its height, the gulag system counted hundreds of different labor camps that contained anywhere from 2,000 to 10,000 prisoners each.

These inmates were usually a mix of common criminals and political prisoners who’d fallen on the wrong side of Stalin’s “Great Purge.” Forced to work long days in difficult conditions, many died of starvation, disease, or the elements. Some were simply executed without warning.

The Kengir gulag, situated just north of the city of Zhezqazghan in the heart of Soviet Kazakhstan, had been built in 1948 to hold political prisoners. Under Soviet law, that category was exceptionally broad, covering both genuine political dissidents and those who were simply unlucky enough to have made the wrong comment at the wrong time.

Of all the Soviet gulags, Kengir was one of the most diverse. Within its walls toiled more than 5,000 people from over a dozen countries. They came from a wide variety of different backgrounds.

But in the spring of 1954, these prisoners all had one thing in common: They were hopeful that Stalin’s death and Beria’s subsequent downfall would bring changes to the gulag. Perhaps they would even be able to earn their freedom. But as time dragged on, they began to realize that the guards had no intentions of letting them go.

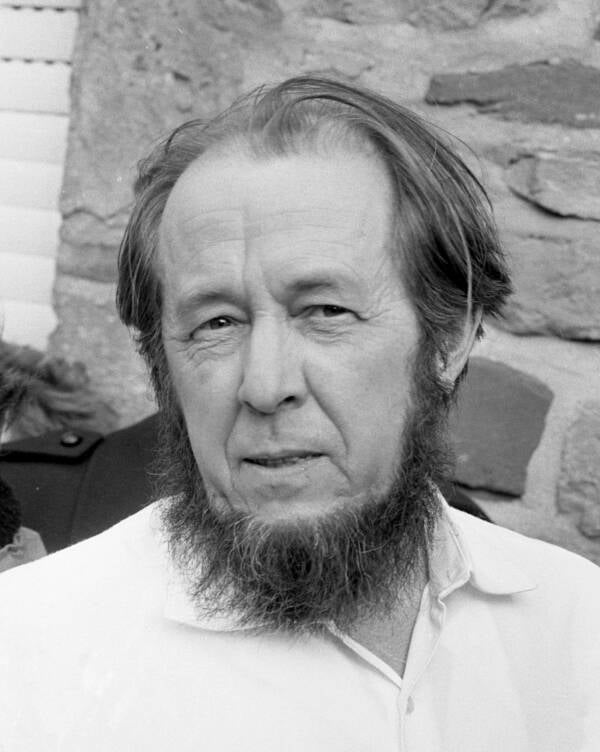

“Nearly a year had gone by since Stalin’s death, but his dogs had not changed,” wrote Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, a witness to the Kengir uprising, in his book Gulag Archipelago. “In fact, nothing at all had changed.”

However, Stalin’s death and the execution of Beria had thrown the gulag system into a state of confusion. Guards no longer felt secure in their roles, and the prisoners whom they oversaw sensed weakness.

“[The guards] had no idea what was required of them and mistakes could be dangerous!” noted Solzhenitsyn. “If they showed excessive zeal and shot down a crowd they might end up as henchmen of Beria. But if they weren’t zealous enough, and didn’t energetically push the strikers out to work — exactly the same thing could happen.”

Confused, nervous, and eager to prove their worth, guards at Kengir took out their frustrations on prisoners, killing several in cold blood for trivial offenses. Solzhenitsyn recorded the deaths of “Lida, the young girl from the mortar-mixing gang,” “the old Chinaman,” and “Aleksandr Sisoyev,” a man who was once called “The Evangelist” by his fellow prisoners.

Arbitrary deaths like these enraged the prisoners — and set the stage for the Kengir uprising. After years of brutality, near-starvation, and back-breaking labor, the frustrations of gulag inmates finally boiled over in May 1954.

The Beginning Of The Bloody Kengir Uprising

Wikimedia Commons/Kaunas 9th Fort MuseumGulag prisoners were forced to work for up to 14 hours a day, six days a week.

Initially, the prisoners responded to the increasing violence at the camp by striking. Multiple divisions refused to report for work for several days in a row, demanding justice for their murdered comrades.

Desperate to regain control, camp commander Colonel Alexander Chechev announced that about 600 “thieves” — prisoners who were convicted of criminal offenses — would be added the camp population.

“[The camp guards] reached for the biggest stick they could,” wrote Solzhenitsyn. “For the thieves!”

In the past, the thieves had reliably terrified political prisoners into submission, maintaining order in the camp with shivs and clubs.

But this time was different. These thieves had heard of the political prisoners’ resistance and admired them. Before long, they joined forces.

Together on May 16, 1954, the two groups tore down the stone walls that separated the men’s camp from the women’s. The gulag guards opened fire, killing almost a dozen prisoners in the process.

But after a series of negotiations, ceasefires, and bouts of violence, the prisoners succeeded in chasing the guards out of Kengir. And for 40 days, they would have a brief taste of freedom.

Life Inside The Liberated Camp

Wikimedia Commons/Kaunas 9th Fort MuseumPolitical prisoners at the Kengir gulag.

After the Kengir uprising, the prisoners celebrated their newfound liberation, but they also quickly got to work. Before long, the inmates would transform the camp into a surprisingly sophisticated society — thanks to the help of prisoners who had experience in politics and the military.

They established their own elaborate system of government that included a new military, a technical team, a food department, an internal security team to monitor any prisoners who wanted to surrender to Soviet authorities, and even a propaganda department to criticize the overthrown camp guards.

As for the high-ranking governing committee, an ex-Red Army officer named Colonel Kapiton Kuznetsov was chosen to lead it.

But despite rebelling against the Soviet gulag, these Kengir rebels were vocal about their support for the Soviet Union as a state. They hung banners around the camp with slogans like “Long live the Soviet constitution!” As Kuznetsov explained: “Our salvation lies in loyalty. We must speak to Moscow’s representatives in a manner befitting Soviet citizens.”

Aside from the provisional government, prisoners also made time for leisure. After all, they were free — for the moment — from a rigid work schedule they’d followed for years. The standard sentence for a gulag inmate was 10 years, and many had been in captivity since the end of World War II.

“Eight thousand men, from being slaves, had suddenly become free,” wrote Solzhenitsyn. “And now was their chance to… live!”

Plays were staged, lectures were held, and one prisoner even set up a café serving something that resembled coffee. Male and female prisoners who were once only able to communicate through letters enjoyed impromptu marriages that were officiated by imprisoned priests.

But no one was under any illusions that this freedom would last forever. The prisoners often broadcasted radio messages and sent letters via pigeons and kites to nearby civilians — explaining how much danger they were in at the camp and outlining their demands to improve their living conditions.

The camp authorities similarly broadcasted messages to the rebels, urging them to surrender. They also sent representatives under the command of Sergei Yegorov, the deputy chief of the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD), in an attempt to negotiate with the strike committee.

Meanwhile, the prisoners readied themselves for the attack that was surely coming. They prepared Molotov cocktails, pikes, and the few firearms seized from the armory. And they even placed buckets of ground glass around the camp, intending to blind any soldiers who might rush in.

After a few glorious weeks of the new society, Soviet troops would take over the camp once more — killing up to hundreds of rebels in the process.

The Soviet Authorities’ Violent Response

Wikimedia CommonsForty days after the Kengir uprising began, Soviet soldiers charged into the camp and quashed the rebellion.

For over a month, the Kengir uprising carried on as Yegorov and the MVD tried to persuade the prisoners that their cause was doomed. But the prisoners refused to budge until certain conditions were met.

They wanted criminal charges brought against the guards who’d murdered their friends. In addition, they wanted their work conditions to be improved. They also wanted a formal recognition of some of their legal rights.

Finally, Sergei Kruglov, the Minister of Internal Affairs of the Soviet Union, lost his patience. He ordered Yegorov to use “all possible resources” to bring the embarrassing uprising to an end and regain control of the camp.

Yegorov gathered 1,700 troops, five T-34 tanks, and nearly 100 attack dogs. Just before dawn on June 26, flares were launched over the camp. Loudspeakers surrounding the fence blasted shrill warnings that any prisoners who resisted the army charging into the camp would be shot.

But many of the prisoners still chose to resist. Using handmade grenades, pistols, picks, iron bars, and stones, they attempted to fight back. But it wasn’t enough. Soviet troops soon swarmed the entire camp — and their tanks crushed anyone standing in their way.

Within 90 minutes, the troops had regained control of the camp. Yegorov’s official report later claimed that 37 had been killed, nine more died of their wounds, and 109 more had been wounded. But the surviving prisoners would tell a far different story. Solzhenitsyn claimed that as many as 700 prisoners had been slaughtered in the effort to retake the camp.

Kuznetsov made an extensive confession to the authorities almost immediately. Shockingly, he also claimed that the true masterminds of the Kengir uprising were a mysterious group known as “the Center.” But if this group truly existed, its members were never identified.

The Legacy Of The Kengir Uprising

Wikimedia Commons/Dutch National ArchivesAleksandr Solzhenitsyn wrote extensively about the gulag system and Kengir in particular.

While the Kengir uprising wasn’t the only gulag rebellion, it was perhaps the most significant, especially since prisoners enjoyed a relatively long period of freedom in the aftermath. But sadly, their freedom didn’t last long.

Still, camp authorities were eager to keep the uprising out of the public eye. So they quietly dispersed the surviving Kengir rebels to separate camps, allowing them to serve out their sentences elsewhere.

By the end of the 1950s, nearly all of the survivors had been released, either when their sentences finished or when they were granted amnesties.

Solzhenitsyn would later shed light on the rebellion when he published The Gulag Archipelago, a sprawling account of his time in the gulag, in the early 1970s. His book brought the truth of the revolt to international attention.

Despite the brutal end of the rebellion, the Kengir prisoners did make an impact on the Soviet Union. Shortly after the crackdown at Kengir, the Central Committee of the Communist Party issued a decree limiting workdays to eight hours. They also announced that it would be possible for prisoners to earn their freedom through hard work and good behavior.

Meanwhile in Moscow, Soviet leaders were beginning to realize how unprofitable the gulags were. Most camps required extensive subsidies to operate, and the guards’ salaries were draining a large chunk of the budget.

In 1956, future premier Nikita Khruschev delivered his “Secret Speech,” in which he attacked Stalin for arresting and deporting so many of his opponents and abusing his power as premier. Not long afterward, Khruschev began closing down some of the larger gulag camps.

Finally, in 1960, the MVD dissolved the gulag system entirely. Solzhenitsyn responded: “The grass on graves is usually very thick and green.”

The era of the gulags had ended. But prison labor continues to exist in former Soviet republics to this day.

After learning about the Kengir uprising, take a look at these disturbing photos of life inside gulag camps. Then, read about Norilsk, the Siberian city founded by gulag prisoners at the edge of the world.