A child of former slaves, Mary McLeod Bethune achieved the near-impossible when she became an advisor to five different U.S. Presidents in the Jim Crow era.

In 1929, the poet Langston Hughes and the educator Mary McLeod Bethune traveled from Florida to New York City together. Bethune didn’t worry about finding hotels and restaurants that would accept her and Hughes in the Jim Crow South. Instead of searching out segregated accommodations, she called on a wide network of supporters.

“Colored people along the eastern seaboard spread a feast and opened their homes wherever Mrs. Bethune passed their way,” Hughes explained. “Chickens, sensing that she was coming, went flying off frantically seeking a hiding place. They knew a heaping platter of southern fried chicken would be made in her honor.”

Public DomainA portrait of Mary McLeod Bethune from 1920, the year she faced down the KKK.

This was a testament to her character as an outspoken advocate and change-maker for Black people in America. As the daughter of enslaved people, Bethune founded a college, led the fight for Black women’s rights, and even in the era of Jim Crow, became an advisor to five United States presidents.

Her decades of tireless work laid the groundwork for the civil rights movement. This is her story.

Who Was Mary McLeod Bethune?

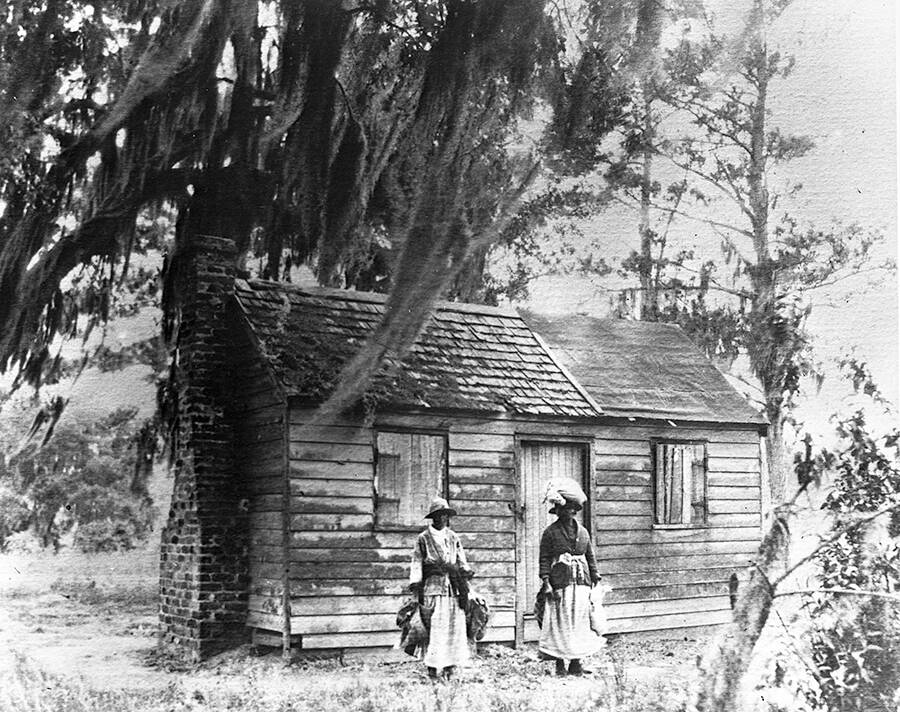

State Archives of Florida, Florida MemoryThe cabin where Samuel and Patsy McIntosh McLeod raised 17 children in Mayesville, South Carolina, circa 1870.

Born in South Carolina a decade after the emancipation of America’s slaves on July 10, 1875, Mary McLeod was the 15th of 17 children. Both of parents had been born into slavery.

Her family also owned their own farm where they grew cotton, and by the time Bethune was nine years old, she could pick 250 pounds of cotton in a single day.

Bethune’s parents supported her education and sent her to a seminary in North Carolina and then to the Moody Bible Institute in Chicago. Though she made great strides in her own life, by 1895, new laws pushed Black voters out of the polls and codified white supremacy.

Bethune fought against the oppression of Black voices by returning to the South as a teacher where she could empower young people.

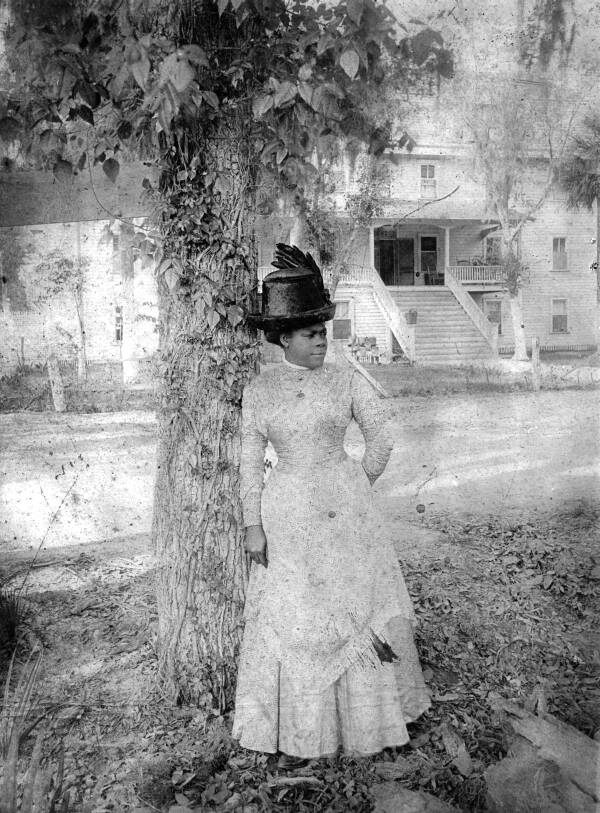

State Archives of Florida, Florida MemoryA circa 1904 portrait of Mary McLeod Bethune, around the time she moved to Florida.

After a brief marriage and separation, Bethune and her son Albert moved to Daytona, Florida. To support her family, Bethune founded the Educational and Industrial Training School for Negro Girls in 1904, which was dedicated to educating Black girls.

“Negro women have always known struggle,” Bethune said in 1920. “This heritage is just as much to be desired as any other. Our girls should be taught to appreciate it and welcome it.”

In 1923, Bethune’s institute merged with a men’s institute to become Bethune-Cookman College.

Mary McLeod Bethune Registers Black Women Voters

In 1920, the 19th Amendment extended the right to vote to women. But Mary McLeod Bethune knew the law would apply differently to white and Black women, and so she spent much of 1920 registering Black voters in Daytona, Florida.

Thanks to Bethune’s efforts, the number of new Black voters quickly outpaced new white voters.

But Bethune’s work triggered a backlash. The Ku Klux Klan marched on her boarding school, returning again in 1922. The second time, a hundred KKK members carried banners touting white supremacy.

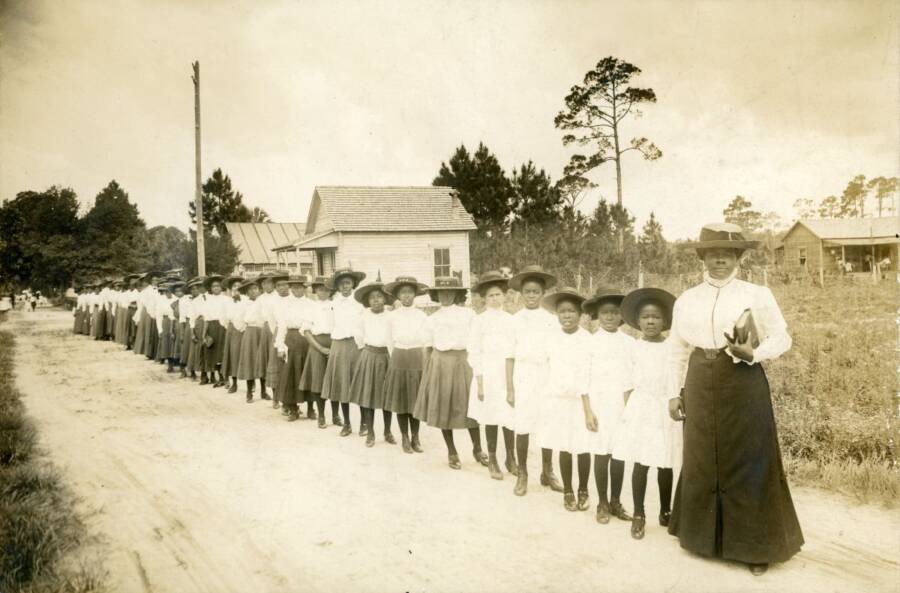

State Archives of Florida, Florida MemoryMary McLeod Bethune stands with her students at the Daytona Educational and Industrial School for Negro Girls, circa 1905.

“Get the students into the dormitory,” Bethune said, thinking quickly. “Get them into bed, do not share what is happening right now.” She then warned the faculty that the KKK mob planned to burn down the school.

Bethune met the Klansmen face on, backed by dozens of armed supporters. The Klansmen quickly turned around and left the boarding school.

But education was just one tool that she used to fight for civil rights. In 1911, Bethune opened McLeod Hospital, the first in the Daytona area that admitted Black patients. The hospital also trained nurses and cared for the poor.

When the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic struck, McLeod Hospital turned to the school. Students set down their books to care for the ill. “The Institution spared neither pains nor money in the discharge of this important duty,” reported Bethune’s friend Frances Reynolds Keyser. “And the spread of the disease was checked.”

From Local Politics To The National Stage

The national stage called to Mary McLeod Bethune. In 1924, she became the president of the National Association of Colored Women (NAACP) and was numbered among the ten most outstanding women living in America in 1931.

Bethune then relocated to Washington, D.C. where she quickly became friends with Eleanor Roosevelt. Roosevelt was a champion for women’s rights and more progressive on civil rights than her husband, Franklin D. Roosevelt. The two women made a point of appearing in public as a way to rebuke racial segregation.

State Archives of Florida, Florida MemoryEleanor Roosevelt and Mary McLeod Bethune in 1937.

Thanks to her connection with the Roosevelts, Bethune secured a leadership role in President Roosevelt’s Federal Council on Negro Affairs, known colloquially as the Black Cabinet. The Black Cabinet pushed for anti-lynching laws, fought against poll taxes, and drafted the executive order that ended segregation in the army.

With her national platform, Bethune also advocated for the government to extend New Deal policies to Black Americans. At the time, racist policies permeated every facet of the American government, like the National Recovery Administration which authorized lower wages for Black workers, and the Federal Housing Authority pushed a redlining policy that kept Black home buyers out of white neighborhoods.

Gordon Parks/Library of CongressMary McLeod Bethune leaving Bethune-Cookman College, where she served as president.

Bethune, the only Black woman in FDR’s inner circle, used her position to fight against those laws, and in 1936, the president named Bethune the head of the Office of Minority Affairs in the National Youth Administration. Bethune suddenly became the highest-ranking Black woman in the administration.

She was also the highest-paid Black government official thanks to her $5,000 annual salary. As director, Bethune made sure funding flowed equally to Black and white Americans. She also founded a Negro College and Graduate Fund that helped over 4,000 Black students fund their college degrees.

Her Legacy And Most Inspiring Words

Afro American Newspapers/Gado/Getty ImagesBethune, then Vice President Harry S. Truman, Ralph Bunche and Vijaya L. Pandit at a conference in 1940.

During World War II, Mary McLeod Bethune linked civil rights with patriotism.

In a 1941 speech she said, “Despite the attitude of some employers in refusing to hire Negros to perform needed, skilled services, and despite the denial of the same opportunities and courtesies to our youth in the armed forces of our country, we must not fail America and as Americans, we must not let America fail us.”

Bethune became vice president of the NAACP in the 1940s and sat on the Women’s Army Corps advisory board, which she fought to integrate.

President Harry Truman appointed Bethune to attend the first United Nations conference in 1945, where she was the only woman of color in the U.S. delegation. At the conference, Bethune pushed for a more expansive and inclusive human rights language in the U.N. Charter.

Carl Van Vechten/Library of CongressA 1949 portrait of Mary McLeod Bethune.

Mary McLeod Bethune died in 1955, and even her death shattered glass ceilings. She became the first Black woman with a national monument in Washington, D.C, and her name continues in Bethune-Cookman University, a top-ranked historically Black university.

In her last will and testament, Bethune said ever optimistically:

“I leave you hope. The Negro’s growth will be great in the years to come. Yesterday our ancestors endured the degradation of slavery, yet they retained their dignity. Today, we direct our strength toward winning a more abundant and secure life. Tomorrow, a new Negro, unhindered by race taboos and shackles, will benefit from more than 330 years of ceaseless struggle. Theirs will be a better world. This I believe with all my heart.”

After reading about Mary McLeod Bethune, learn about other Black leaders who shaped history. Then, read about the resistance to the civil rights movement.