While many Americans are taught that the civil rights movement was localized in the South in the 1950s and '60s, the reality is that the struggle was brutal all over the country.

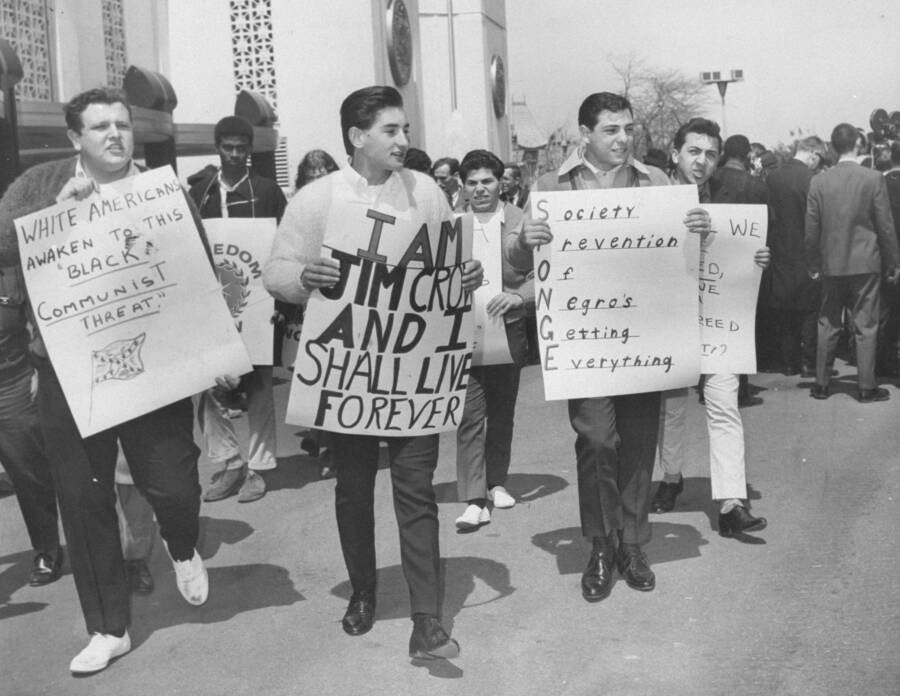

New York Daily News Archive/Getty ImagesPro-segregation members of SPONGE (Society of the Prevention of Negroes Getting Everything) picket CORE (Congress of Racial Equality) workers outside the New York Pavilion at the World’s Fair in 1965.

In 1956, U.S. Senator Harry Byrd of Virginia responded to the civil rights movement by rallying against the national desegregation of public schools. He said, “If we can organize the Southern states for massive resistance to this order, I think that in time the rest of the country will realize that racial integration is not going to be accepted in the South.”

In practice, this “massive resistance” often meant harassing Black students, bombing schools, and attacking civil rights activists. But even though Byrd’s call-to-action spoke to many white Southerners, opposition to the civil rights movement was certainly not restricted to the South.

In 1963, polls showed that 78 percent of white Americans would leave their neighborhoods if Black families moved in. Meanwhile, 60 percent of them had an unfavorable view of Martin Luther King Jr.’s March on Washington.

From New York to California, the anti-civil rights movement was widespread throughout the country. And many white Americans were not afraid to say they supported it.

Bombingham, Dynamite Hill, And Segregated Neighborhoods

Bettman/Getty ImagesA family watches a KKK cross burning from their car in an undisclosed location in the South in 1956.

At first, white Americans tried to preserve all-white neighborhoods using the law. But if the law failed, they sometimes turned to terrorism.

In the 1950s, Center Street was the color line of Birmingham, Alabama. White families traditionally lived on the west side of Center Street. But after Black families began moving into the area, the bombings began.

“There were 40-plus bombings that took place in Birmingham between the late ’40s and the mid ’60s,” said historian Horace Huntley. “Forty-some unsolved bombings.”

Those bombings terrorized Black homeowners and gave Center Street a new nickname: Dynamite Hill. By that point, Birmingham itself had already been given its own notorious nickname: Bombingham.

At first, members of the Ku Klux Klan burned the doors of the homes that Black people moved into. Sometimes, they would fire shots into the night. But soon came the dynamite, which was often thrown by the white supremacists.

“Terrorism is nothing new to us,” says Jeff Drew, who grew up in Dynamite Hill. “We were terrorized back in the ’50s and ’60s almost every day. It was commonplace.”

Drew even remembers the Klan calling his father to say, “We gon’ bomb your house tonight.” Drew’s father responded, “What you call me for? Come on, come on. Do it right now. You don’t have to call me. Just come on,” and hung up the phone.

The bombers targeted the home of civil rights lawyer Arthur Shores multiple times. “Bullet shots through the window [were] frequent,” said Helen Shores Lee, Arthur’s daughter. “We had a ritual we followed: You hit the floor and you crawled to safety.”

Racial Violence Affected Many American Cities

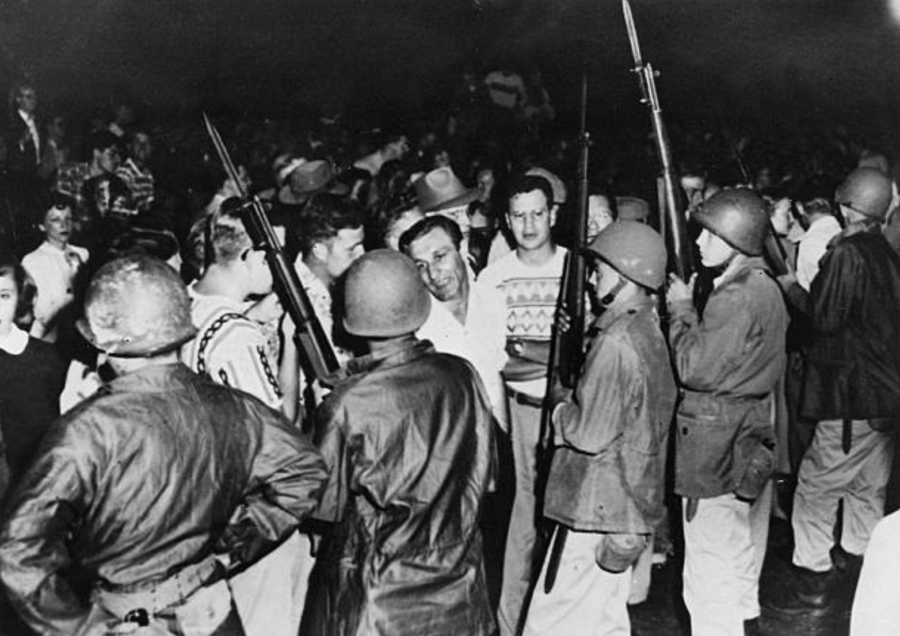

ullstein bild/Getty ImagesThe Cicero riot of 1951. After just one Black family moved into a white neighborhood in Cicero, Illinois, a mob of 4,000 white people attacked the entire apartment building.

“Bombingham” was not the only place where Black residents faced threats of violence. Similar incidents occurred in other cities across America.

In Philadelphia, more than 200 Black people who tried to rent or buy homes at the edges of the city’s segregated districts were attacked during the first six months of 1955 alone. And in Los Angeles, over 100 African Americans were targeted with violence when they attempted to move out of segregated neighborhoods between 1950 and 1965.

On July 11, 1951, one of the biggest race riots in U.S. history erupted after just one Black family moved into an apartment in the all-white town of Cicero, Illinois. The husband, Harvey Clark Jr., was determined to get his wife and two kids out of a crowded tenement on Chicago’s South Side.

But when the World War II veteran tried to move his family into his new place, the sheriff told him, “Get out of here fast. There will be no moving into this building.”

After Clark returned with a court order in hand, he finally moved his family’s belongings into the apartment. But they weren’t able to stay a single night in their new home, due to the racist white mob that had gathered outside. Before long, the mob numbered up to 4,000 people.

Even after the family fled, the mob didn’t leave. Instead, they stormed into the apartment, threw the furniture out the window, and tore out the sinks. Then, they firebombed the entire building, leaving even the white tenants without a home.

A total of 118 men were arrested for rioting, but none of them were ever indicted. Instead, the agent and the owner of the apartment building were indicted for causing the riot by renting to a Black family in the first place.

APRace massacres were nothing new in America. Even before the civil rights movement kicked off in the 1950s, the country was plagued by riots, like this one in Detroit in 1943.

Riots weren’t the only things keeping American neighborhoods segregated — several government policies played a role as well. The Federal Housing Administration (FHA), which was formed in 1934, often refused to insure mortgages in and near African-American neighborhoods. This policy is now known as redlining — and it was commonplace all across the country.

Some cities also enacted zoning policies to keep neighborhoods segregated. For instance, exclusionary zoning banned multi-family homes and apartments in certain areas, limiting Black residents’ access to all-white neighborhoods. Meanwhile, the FHA manual argued that “incompatible racial groups should not be permitted to live in the same communities.”

The FHA even recommended “racial covenants” where neighborhoods promised to never rent or sell their property to a Black buyer.

During Desegregation, White Parents Withdrew Their Children From School

Bettmann/Getty ImagesWhen Elizabeth Eckford arrived at school for her first day in 1957, her fellow students attacked her for integrating their classes.

The battle over school segregation didn’t end when the Supreme Court ruled it unconstitutional in 1954. For decades, countless white parents continued to fight against desegregating schools.

They pulled their kids out of public schools, moved them into private schools where they’d only be around white children, and harassed any Black students who wanted to integrate.

On Sept. 4, 1957, nine Black teenagers arrived at Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas for their first day of classes. When 15-year-old Elizabeth Eckford showed up to the formerly all-white school, an angry mob and armed soldiers blocked her path.

“I remember this tremendous feeling of being alone,” Eckford later recalled. “I didn’t know how I was going to get out of there. I didn’t know whether I would be injured. There was this deafening roar. I could hear individual voices, but I was not conscious of numbers. I was conscious of being alone.”

White students refused to enter the school until the soldiers turned away the Black students. Many teens said that if Black students were allowed in, they would refuse to attend classes.

Bettmann/Getty ImagesWhite students taunt Black students with a racist sign outside of a Baltimore high school.

It took more than two weeks before the Little Rock Nine were finally allowed to attend classes. But a furious mob still surrounded the school, threatening the Black students and trying to rush inside. After just three hours of classes, the students were sent home for their own safety.

And for the rest of the school year, white high schoolers continued to harass the Little Rock Nine.

Although intimidation didn’t keep the school segregated, the state soon passed a new law allowing school districts to shut down to avoid integration. So during the 1958-1959 school year, Little Rock closed four high schools. This forced thousands of students — including white students — out of class.

Sometimes politicians encouraged the counter-movement against integration. In 1963, Alabama Governor George Wallace personally intervened to stop Tuskegee High School from integrating, blocking 13 Black students from attending classes.

In a matter of days, every single white student at the school had transferred, with most enrolling at a new all-white private school. Tuskegee High School was forced to close in January 1964.

White Protesters Threatened To Kill A Black Six-Year-Old

John T. Bledsoe/Library of CongressProtestors at the Little Rock state capitol carry signs reading, “Race Mixing is Communism” and “Stop the Race Mixing March of the Anti-Christ.” This 1959 rally protested the integration of Little Rock schools.

Little Rock was not an isolated incident. Across the South, the White Citizens’ Councils signed up 60,000 members who carried out a massive resistance to the desegregation of public schools. Not only did they harass Black students and activists, they also blatantly encouraged racial violence.

At one White Citizens’ Councils rally in Alabama, a handbill declared, “When in the course of human events it becomes necessary to abolish the Negro race, proper methods should be used. Among them are guns, bow and arrows, slingshots and knives.”

Getty ImagesJust one day after Hattie Cotton Elementary School integrated in 1957, a segregationist bombed the building.

While Black high schoolers were often targeted with harassment, some segregationists lashed out at students who were far younger. In 1960, Ruby Bridges became the first Black student to attend an all-white elementary school in the South — and she was greeted by an angry white mob.

The pushback against the six-year-old was so intense that she needed federal marshals to escort her to and from class for her own safety. Some of the protestors directly threatened violence against her, screaming, “We’re going to poison her, we’re going to hang her.” One white woman even taunted Ruby with a small coffin that held a Black doll.

Department of JusticeIn 1960, U.S. Marshals escort Ruby Bridges to and from school through a crowd of protestors, some of whom threaten to kill her.

At the demand of white parents, the principal put Ruby in a class of one with the only teacher at the school who would agree to educate a Black child. During lunchtime, Ruby ate alone, and during recess, she played alone.

Along with tormenting the child, the white segregationists also targeted her family. Ruby’s father was fired from his job and her grandparents were kicked off their farm. Grocery stores refused to sell food to Ruby’s mother.

The anti-civil rights movement was determined to stop desegregation from happening in the first place. But if schools did end up integrating, opponents vowed to make integration as difficult as possible.

Opponents Of Civil Rights Attacked Activists

Bettmann/ContributorDuring a 1966 march in Chicago, hecklers hit Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in the head with a rock.

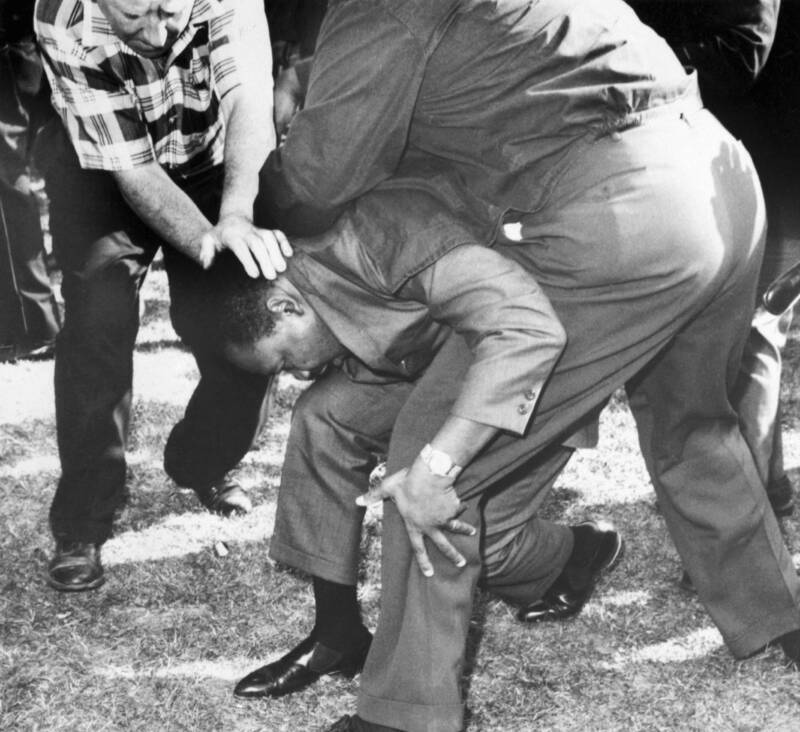

Beatings, lynchings, and bombings became the most violent tools of the anti-civil rights movement. Perhaps one of the most shocking cases was the Freedom Summer Murders.

In 1964, a Mississippi deputy sheriff arrested three civil rights activists: Andrew Goodman, James Chaney, and Michael Schwerner. These three men had initially traveled to Mississippi to register Black voters. However, they also wanted to investigate church burnings in the area.

But after they set out to investigate, that’s when they were arrested. The deputy sheriff first acted like he was going to let them go — but then he arrested them again and handed them over to the Ku Klux Klan. The Klan members shot and killed all three of them. While the murderers were put on trial, a sympathetic jury found them not guilty.

Eventually, the federal government charged the killers with violating the civil rights of Goodman, Schwerner, and Chaney. And this time they were convicted — but they only served sentences ranging from two to 10 years.

There’s no question that civil rights activists felt unsafe in the South. But that didn’t mean the North was much better — in fact, some activists even felt less comfortable in Northern cities.

On August 5, 1966, Martin Luther King Jr. led a march through an all-white neighborhood in Chicago. And in response, counter-protesters threw bottles and bricks at the demonstrators. One rock struck King right on the head.

“I have seen many demonstrations in the South but I have never seen anything so hostile and so hateful as I’ve seen here today,” King said of the Chicago march.

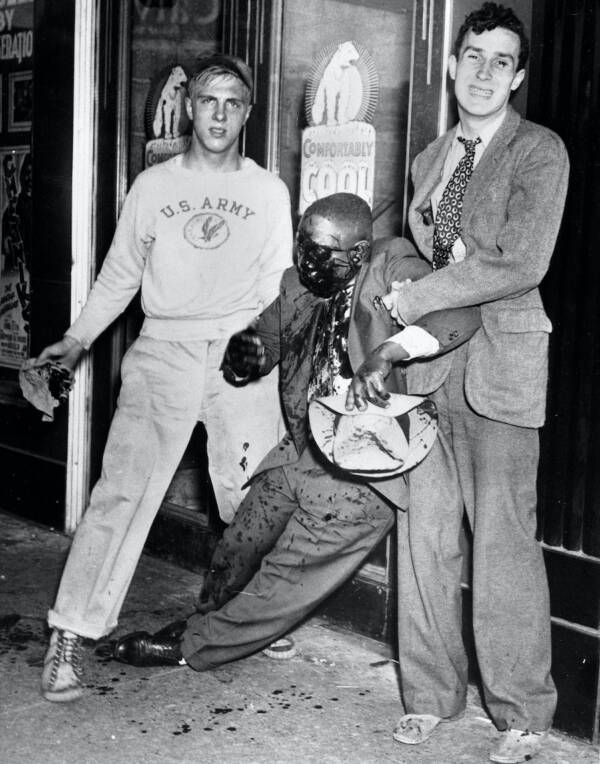

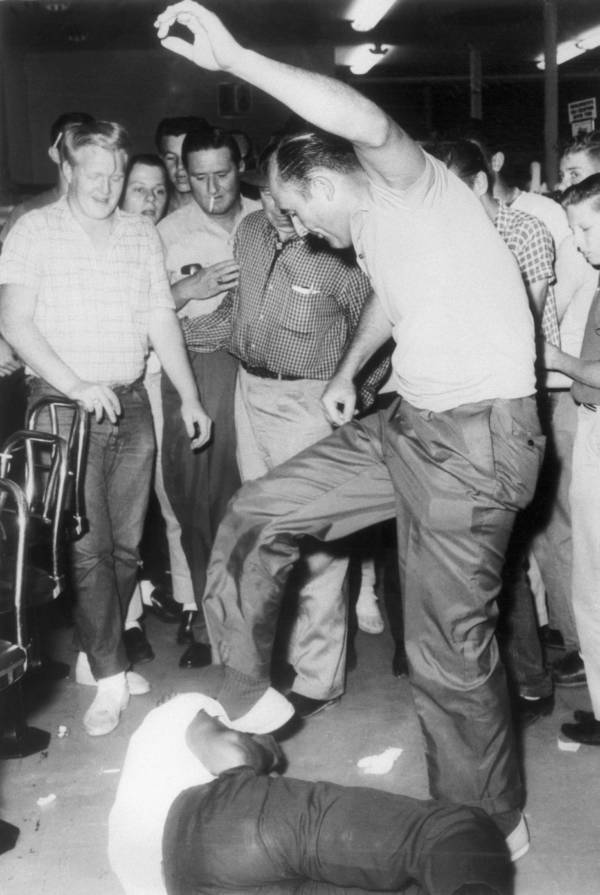

Bettmann/Getty ImagesBenny Oliver, a former police officer, kicks Memphis Norman, a Black student who placed an order at a segregated lunch counter in Mississippi in 1963. Onlookers cheered the beating.

But civil rights leaders didn’t back down in the face of violence. Instead, they devised a strategy to harness the hostility to fuel their movement.

On March 7, 1965, civil rights demonstrators crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama to find a wall of state troopers, county sheriffs, and white counter-protestors with Confederate flags. When the troops advanced, the protestors braced themselves for a brutal attack.

And the cameras were rolling — capturing every vicious beating in sight. Just weeks before the march in Selma, King had told a Life magazine photographer not to put down his camera to help protestors when authorities attacked them during the marches. “The world doesn’t know this happened because you didn’t photograph it,” King scolded.

After the Selma March, nearly 50 million Americans watched the ruthless assault now known as Bloody Sunday on their televisions.

However, many of those Americans criticized civil rights activism during the 1960s. A 1961 Gallup poll reported that 61 percent of Americans disapproved of the Freedom Riders, while only 22 percent approved.

The poll also found that 57 percent of Americans believed protests like sit-ins at lunch counters were hurting the cause of integration, while just 28 percent believed the demonstrations were helping.

The white public also widely disliked civil rights leaders. A 1966 poll found that 63 percent of Americans had a negative view of Martin Luther King Jr. And after he was assassinated in 1968, a study of white schoolchildren in the South found that 73 percent of the boys were “indifferent to or pleased by Dr. King’s murder.”

Authorities Used Their Power To Curb Civil Rights

A 1955 editorial in the Montgomery Advertiser warned, “The white man’s economic artillery is far superior, better emplaced, and commanded by more experienced gunners. Second, the white man holds all the offices of government machinery. There will be white rule for as far as the eye can see. Are those not facts of life?”

The legal system served as a tool of control to uphold this “white rule.” Police often ignored violence against Black victims. Juries usually refused to convict white defendants accused of crimes against Black people. And civil rights demonstrators were typically labeled as “criminals.” Meanwhile, politicians rallied against the civil rights movement on the basis of “protecting” white people.

“The fight to protect our racial identity is basic to our whole civilization,” declared Senator James Eastland of Mississippi in 1955.

Warren K. Leffler/Library of CongressAt the 1964 Republican National Convention, Ku Klux Klan members came out to support Barry Goldwater.

In Alabama, George Wallace made his position on the civil rights movement crystal-clear in 1963. During his inaugural address, Wallace promised, “Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, and segregation forever.”

When Wallace ran for president in 1968 as an independent, he lost the election but he still won a few Southern states: Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Louisiana, and Mississippi. He also snagged over 10 percent of the vote in a few Northern states, such as Ohio, Michigan, and Indiana. All in all, he netted 46 electoral votes total.

During the late 1960s, politicians began to call for “law and order,” a thinly-veiled suggestion that the legal system should suppress civil rights demonstrations. According to segregationists, civil disobedience and integration were to blame for the increase in crime.

Shortly after Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in 1968, a Nebraska paper published a letter arguing that he caused “violence and destruction” and “riots and chaos” – and, as a result, no one should honor his memory.

California Gun Control Measures Targeted The Black Panthers

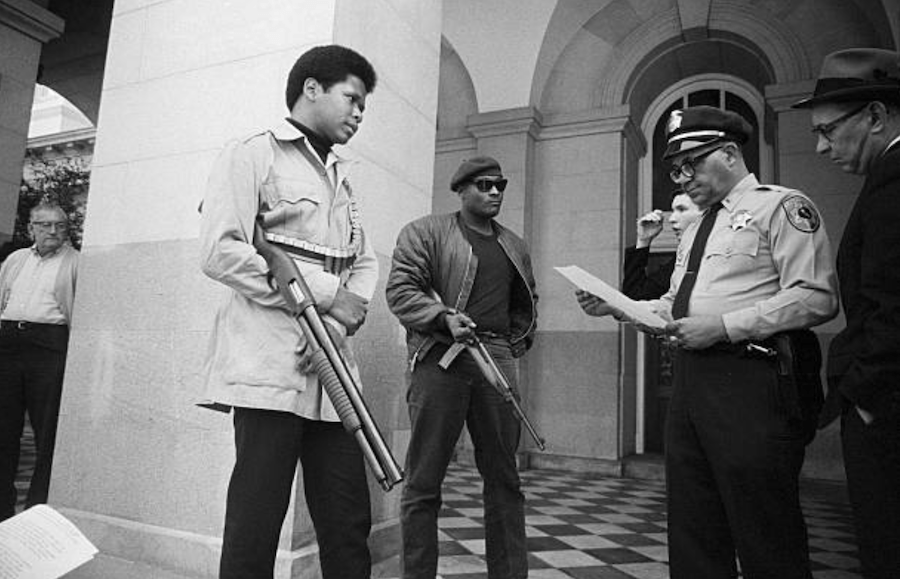

Bettmann/Contributor/Getty ImagesTwo armed members of the Black Panther Party at the state capitol in Sacramento in 1967.

In 1967, 30 Black Panthers stood on the steps of California’s state capitol armed with .357 Magnums, 12-gauge shotguns, and .45-caliber pistols. “The time has come for Black people to arm themselves,” the Black Panthers declared.

In response to the African American activists carrying weapons, California passed some of the strictest gun laws in the country – with the backing of the National Rifle Association.

In the mid-1960s, the Black Panthers began openly carrying guns to protest violence against the Black community and underscore their public statements about the subjugation of African-Americans.

Black Panthers in Oakland also trailed police cars and offered free legal advice to African Americans pulled over by the police.

While the Black Panthers were already a controversial group, the sight of armed Black men in the streets utterly shocked California politicians, including the state’s then-governor, Ronald Reagan.

In 1967, the legislature passed the Mulford Act, a state bill prohibiting the open carry of loaded firearms, along with an addendum prohibiting loaded firearms in the state capitol. It was clearly a response to the Black Panthers.

“The American people in general and the Black people in particular,” Black Panthers co-founder Bobby Seale declared, must “take careful note of the racist California legislature aimed at keeping the Black people disarmed and powerless.”

Boston’s School Busing Policy And White Flight

The anti-civil rights movement didn’t die out after the 1960s ended. It still lingered in places all over America — with some of the most shocking examples in Northern cities like Boston.

On Sept. 9, 1974, over 4,000 demonstrators protested Boston’s school desegregation plan. That year, a court-ordered school busing plan would attempt to integrate schools 20 years after Brown v. Board of Education.

A white city council member created Restore Our Alienated Rights (ROAR) to argue against busing. As Boston’s yellow buses let out Black students, some white people threw stones and bottles at the children. Police in combat gear were often needed to control angry white protesters near the schools.

Boston Globe/Getty ImagesIn 1973, an anti-busing group held a protest against Boston’s school busing plan.

Unlike desegregation protests in the late 1950s and 1960s, the language of the Boston protesters had changed. They were against busing and in favor of “neighborhood schools.” By avoiding explicitly racist language while supporting white schools and neighborhoods, white Bostonians positioned themselves as victims of an activist court order.

But as civil rights leader Julian Bond put it: “What people who oppose busing object to is not the little yellow school buses, but rather to the little Black bodies that are on the bus.”

This was made shockingly clear by a blatant act of violence at one of the anti-busing demonstrations — one that was captured on camera.

Stanley Forman/Boston Herald AmericanKnown as “The Soiling of Old Glory,” this photo later won a Pulitzer Prize for breaking news photography. Boston, Massachusetts. 1976.

On April 5, 1976, a Black lawyer named Ted Landsmark was on his way to a meeting at Boston’s city hall when he was suddenly attacked by a mob. Unbeknownst to Landsmark, he had accidentally walked into an anti-busing protest full of white demonstrators. Before he knew it, he was surrounded.

The first man who attacked him hit him from behind, knocking off his glasses and breaking his nose. Just moments after that, another man lunged at him with the sharp point of a flagpole — with the American flag attached.

Landsmark would later say that the entire incident took about seven seconds. But since a news photographer captured a snapshot, this infamous moment would be preserved forever as “The Soiling Of Old Glory.”

In response to desegregation, many white families left the school district altogether. In 1974, white students made up over half of the 86,000 students in Boston’s public schools. By 2014, fewer than 14 percent of students in Boston public schools were white.

The Legacy Of The Anti-Civil Rights Movement

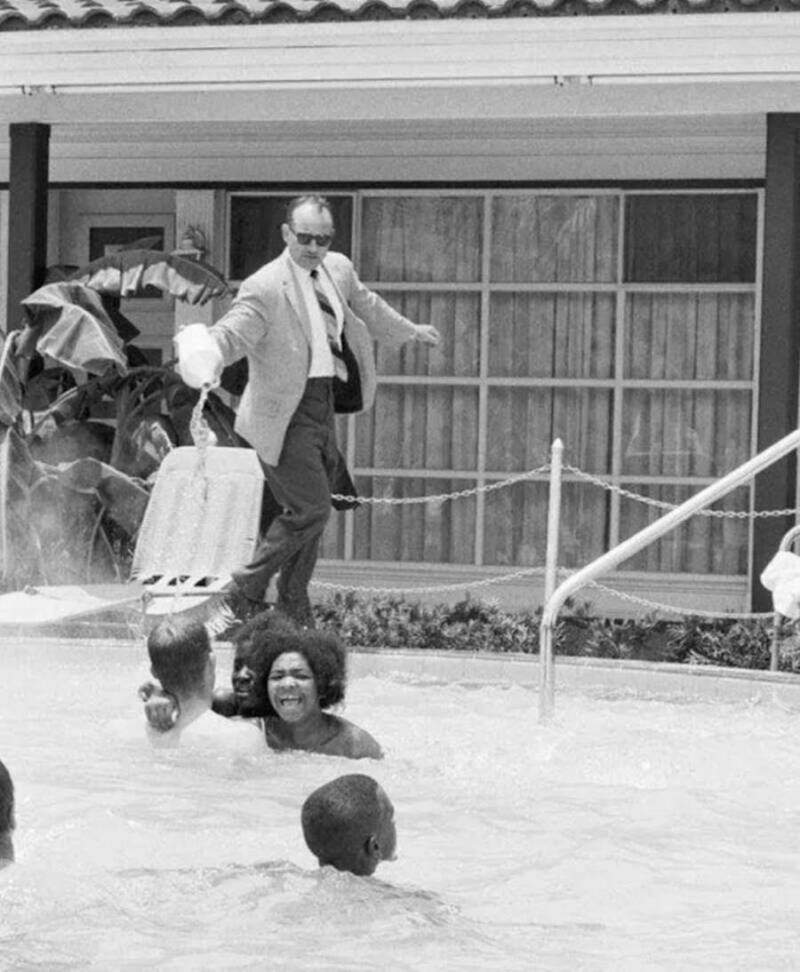

APOn June 18, 1964, Black and white protestors jump into the whites-only pool at the Monson Motor Lodge in St. Augustine, Florida. In an attempt to force them out, hotel owner James Brock dumps acid into the water.

In 1963, the word “backlash” as you know it today was coined to encapsulate the violent reaction that millions of white Americans were having to the civil rights movement. While Black Americans struggled for equality, whites across the country launched a brutal counter-offensive aimed to halt and reverse the march of progress at every turn.

But despite this intense backlash, the civil rights movement saw many impressive victories during this time. The Civil Rights Act was passed in 1964 and the Voting Rights Act was passed in 1965. However, neither piece of legislation was a perfect solution to racial inequality.

During the 1960s, Texas responded to the new laws by putting up 27 Confederate monuments honoring soldiers who fought against “the federal enemy.” Tennessee put up at least 30 Confederate monuments after 1976.

After the 1960s and 1970s, the anti-civil rights movement still saw quite a few blatantly racist demonstrations. But for the most part, the movement often turned to new, less obvious tactics.

Mark Reinstein/Contributor/Getty ImagesAmerican neo-Nazis and members of the KKK rally in Chicago in 1988. From the 1960s to the 1980s, Marquette Park was a site of many racist demonstrations.

As more Black voters joined the electorate, voter suppression became one of those new tactics. A Republican National Committee memo from 1981 promoted removing up to 80,000 voters from the rolls in Louisiana. The memo argued, “If it’s a close race, which I’m assuming it is, this could keep the Black vote down considerably.”

Another tactic was adjusting the language used to further the cause. In 1981, Lee Atwater, an advisor to President Reagan, candidly explained how opposition to the civil rights movement had evolved:

“You start out in 1954 by saying, ‘N*gger, n*gger, n*gger.’ By 1968, you can’t say ‘n*gger’ — that hurts you, backfires. So you say stuff like, uh, forced busing, states’ rights, and all that stuff, and you’re getting so abstract.”

As the counter-movement adapted to the times, residential segregation and the push for neighborhood schools effectively re-segregated public education. Even in Northern and Western population centers, more than four out of five Black residents lived in segregated neighborhoods. By the 1998-1999 school year, schools were more segregated across the nation than they’d been in the 1972-1973 school year.

Today, many places in the United States remain segregated, more than 50 years after the Fair Housing Act of 1968. While some of the most segregated cities in America include Southern cities like Memphis and Jackson, Northern cities like Chicago and Detroit also top the list.

Along with segregation, another issue that has persisted throughout the decades has been the resistance to interracial relationships. It wouldn’t be until the early 2000s that most white Americans said they didn’t disapprove of interracial marriage. Even as late as 1990, 63 percent of non-Black people in a Pew Research Center poll would oppose a family member marrying a Black person. By 2017, that figure stood at 14 percent.

Yet today, some Americans think the fight for civil rights is over. In a 2016 poll, 38 percent of white Americans said the country had done enough to achieve racial equality. Only 8 percent of Black Americans agreed.

After learning about the ongoing fight for civil rights, learn more about the shocking story behind the photo of white students harassing Elizabeth Eckford, and then check out powerful photos of the civil rights movement.