In 1961, Freedom Riders rode between cities in the American South to test federal laws banning racial segregation. They were arrested, threatened, and beaten senseless.

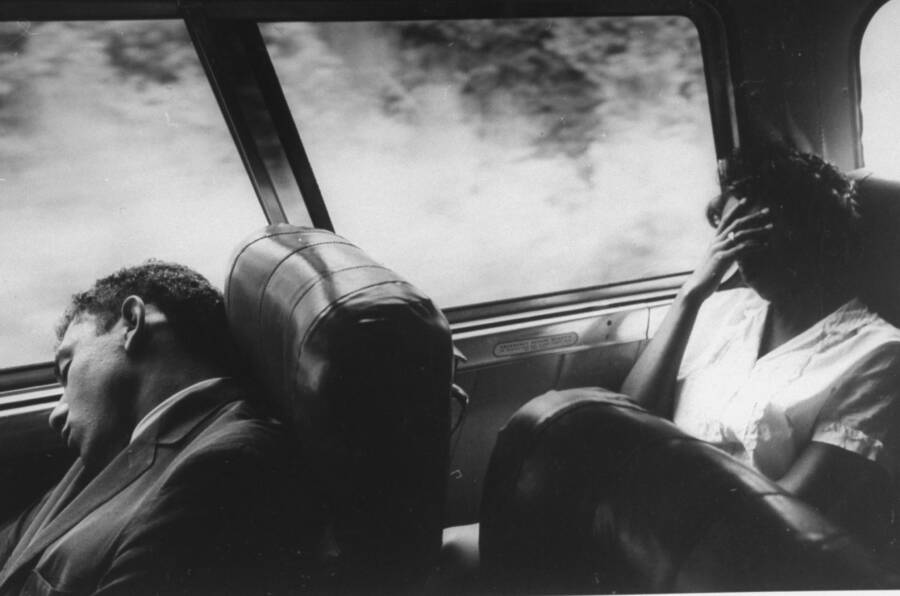

The Freedom Riders were a mixed group of African-Americans and white people who rode between cities in the deep South to test federal laws banning segregation on interstate public transit. While it was illegal to have racially-segregated seats on buses and at bus stops after the law passed, in reality the law was mostly ignored.

The 20-day trip between Washington, D.C., to Jackson, Mississippi commanded the nation's attention after the Freedom Riders were attacked and beaten by racist pro-segregationists.

In a larger sense, these interstate bus rides were about more than securing a seat for black passengers. It was a symbol of the growing resistance from African-Americans and allies against the hateful fire of the nation's systemic racism.

Desegregation Of Public Transportation

Underwood Archives/Getty ImagesRosa Parks gets fingerprinted after her arrest.

The Freedom Riders campaign cannot be explored without first understanding the history of bus desegregation in America.

Many will say the moment that propelled the movement was on Dec. 1, 1955, when an African-American community activist named Rosa Parks got on the bus home after a long day of work and refused to give up her seat to a white passenger when the bus driver told her to.

At the time, bus drivers in Montgomery, Alabama, routinely required African-Americans to give up their seats to white passengers if the whites-only section of the bus was full.

After Parks, who served as the secretary for the National Association for the Advancement of People of Color (NAACP), was taken into custody, local activists began mobilizing for a boycott of the city's bus system.

Members of the Women's Political Council (WPC), an activist organization made up of black women professionals, had been advocating for the equity of Montgomery's black bus passengers years before Parks' bus seat incident.

But the group saw the incident as an opportunity to advance their civil rights work by using Parks' arrest as a catalyst to mobilize residents the same day that Parks was tried in municipal court. Black leaders and ministers also helped promote the planned boycott. The Montgomery Advertiser put out an article about the boycott on its front page.

The result? Thousands of African-Americans boycotted the city's bus system; the city lost between 30,000 and 40,000 bus fares each day of the boycott. Volunteers helped drive boycotters to and from work while black taxi drivers charged 10 cents a ride — the same amount as bus fare — to support the protest.

"It was the best way I could contribute," said Samuel Gadson, who endured harassment for driving boycotters in his 1955 Ford, said.

The black riders made up the majority of bus passengers, so this put huge pressure on the public transit system.

Enter Martin Luther King

Don Cravens/The LIFE Images Collection via Getty Images/Getty ImagesRev. Martin Luther King, then director of the Montgomery bus boycott, outlines strategies to organizers, including Rosa Parks.

A young, black pastor named Martin Luther King, Jr. — who had recently become the pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery — became the face of the boycott and continued to lead it until the city met the demands of local black leaders.

These demands did not seek to repeal the city's segregation ordinance but rather focused on civil decency toward black passengers. Firstly, the group demanded the city change its method of dividing the bus by race.

As it was, the racial dividing line was fluid; a bus driver could move it to whichever row he wanted. Before Rosa Parks was arrested, she had been sitting in the "colored" section of the bus — it was only after more white people got on and the bus driver moved the dividing line back that she was sitting in the white section. That's when she refused to move.

Under the group's proposal — a compromise they thought the city would be more likely to accept — no black passenger would ever be forced to give up their seat for a white passenger. If the white section filled up, then white passengers would be forced to stand.

The group, dubbed the Montgomery Improvement Association, also demanded the city hire black drivers and institute a first-come, first-seated policy.

But the city didn't budge. It was then that a group of five African-American women filed a joint lawsuit against the city in federal court seeking to have Montgomery's bus segregation laws abolished completely, in a case called Browder v. Gayle.

After an appeal by the city, the Supreme Court decided to uphold the decision of the lower court that had ruled any laws requiring racially segregated seating to be in violation of the 14th Amendment.

Following the Supreme Court decision, Montgomery's buses were integrated on December 21, 1956, and the bus boycott finally ended after 381 days.

Although segregated seating had been outlawed, racial tensions continued to flare in Montgomery. Violence against black passengers intensified with sniper hail fire attacking buses and injuring black riders.

Just a few weeks after the Supreme Court decision to integrate the public bus system, four black Montgomery churches and the homes of prominent local black pastors in were bombed. The police later arrested several Ku Klux Klan members for the bombings, but all were acquitted by all-white juries.

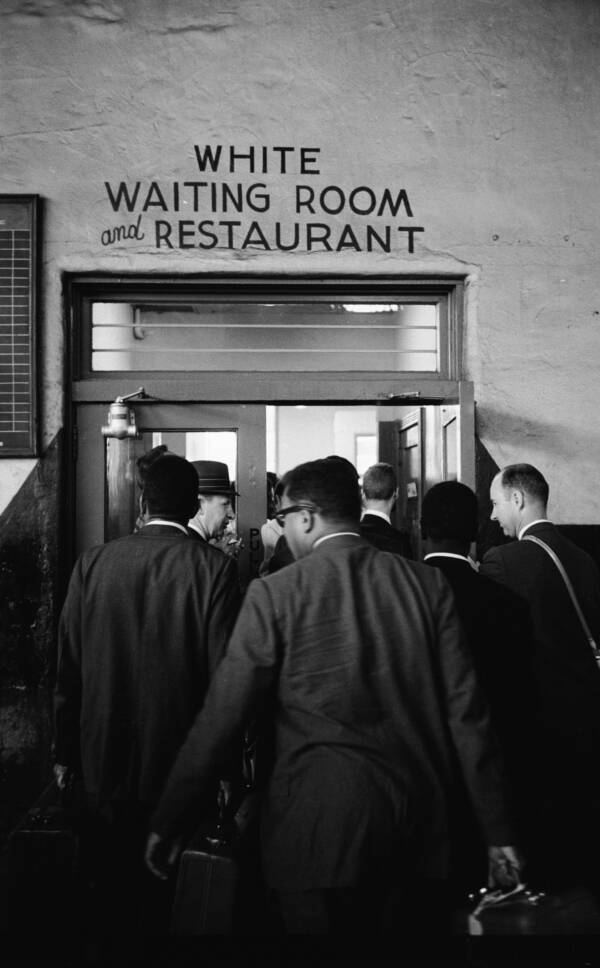

Black passengers were also still unwelcome in predominately white spaces at bus stations, where waiting facilities for white passengers and black passengers remained separate. While the law did away with bus segregation on paper, it was clear that in reality there was much work left to be done.

The Freedom Riders

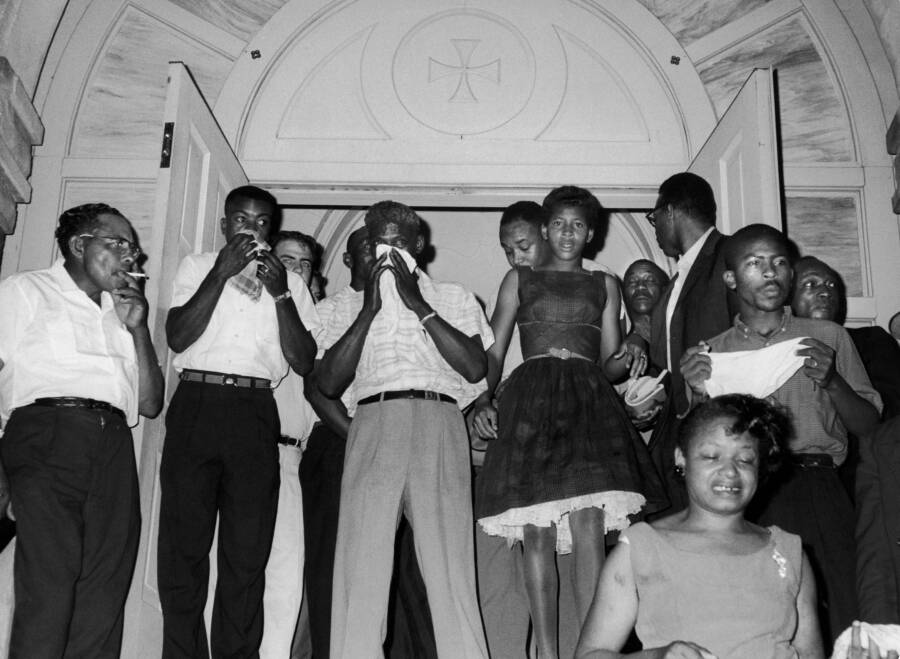

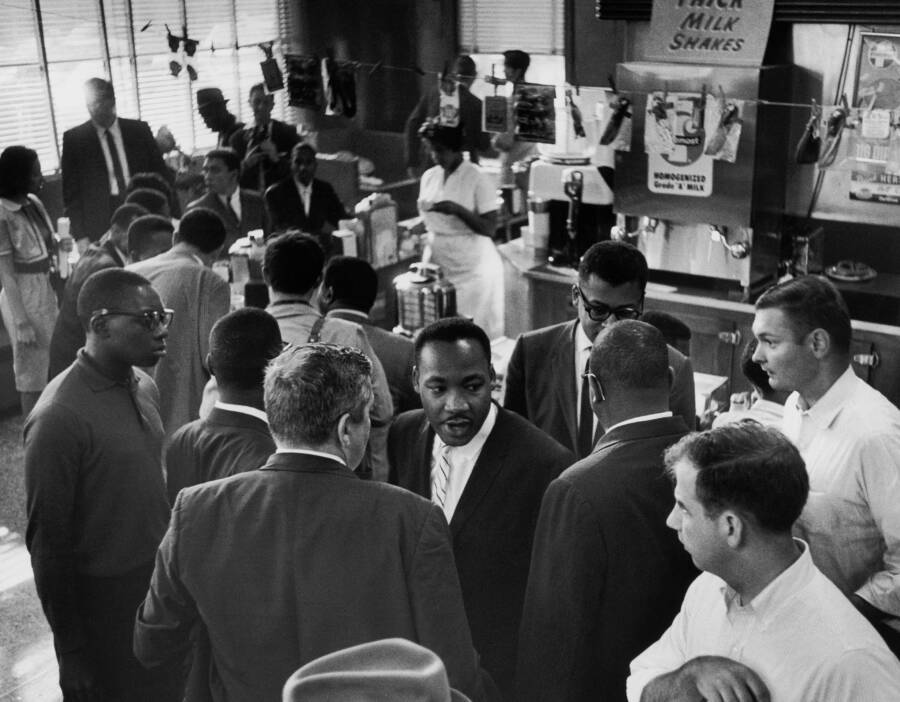

Paul Schutzer/The LIFE Premium Collection/Getty ImagesThe Freedom Riders regroup after being rescued from the white mob surrounding First Baptist Church.

By the early 1960s, the civil rights movement had gained tremendous momentum. Civil rights activists and students were staging protests everywhere, including sit-ins at the segregated lunch counters at public restaurants.

Non-violent and peaceful protest was the soul of the civil rights movement, a method promoted by Martin Luther King, Jr. in his pursuit of racial equality.

In a November 1960 televised debate with a pro-segregationist on NBC titled "Are Sit-In Strikes Justifiable?," King explained the rationale behind these peaceful protests:

"We see here a crusade without violence, and there is no attempt on the part of those who engaged in sit-ins to annihilate the opponent but to convert him. There is no attempt to defeat the segregationists but to defeat segregation, and I submit that this method, this sit-in movement, is justifiable because it uses moral, humanitarian, and constructive means in order to achieve the constructive end."

The influence that these protests bore would be tested in May 1961, when caravans of Freedom Riders drove between states in the infamously racist deep South to bring awareness to the segregationist practices that still permeated public transit — even after it was legally banned by the federal government.

Riding For Freedom

All the way back in 1946, in Morgan v. Virginia, the Supreme Court ruled that Virginia's law enforcing segregation on interstate buses was unconstitutional. The first Freedom Rides happened the next year, in fact, to test the new law. But there were no confrontations, and so the protests garnered very little media attention.

That changed 14 years later. In December 1960, in Boynton v. Virginia, the Court went a step further, banning segregation in bus terminals serving interstate passengers. At this point, desegregation was the hottest of hot-button issues. Black resistance — and white supremacy — were on the rise. And despite rulings from the highest court in the land, Jim Crow remained in full force in the south.

And so a group of activists saw their entry point.

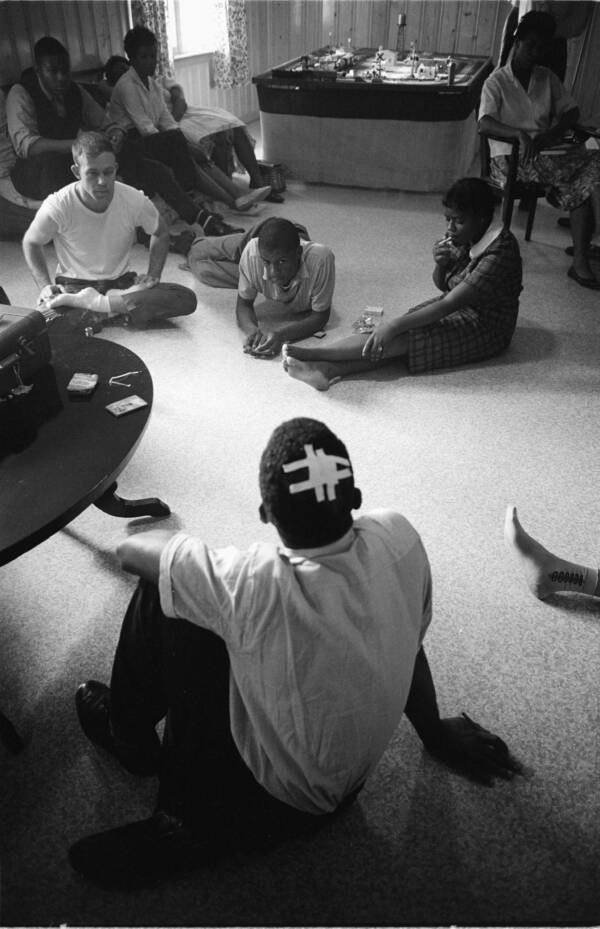

On May 4, 1961, the Congress Of Racial Equality (CORE), a civil rights organization founded on the principles of non-violence promoted by Indian activist Mahatma Gandhi, sent 13 of its members — seven black and six white — to ride on two separate public buses from Washington, D.C. to the deep South.

Over the next several months, CORE's ranks would expand by more than 400 volunteers, all of whom were trained to endure extreme acts of opposition — like being spat on, hit, or screamed at with racial epithets — and remain non-violent.

Making History

According to CORE director James Farmer, the goal of the Freedom Riders campaign was "to create a crisis so that the federal government would be compelled to enforce the law."

It sure seemed like a crisis — at least by the time they reached South Carolina.

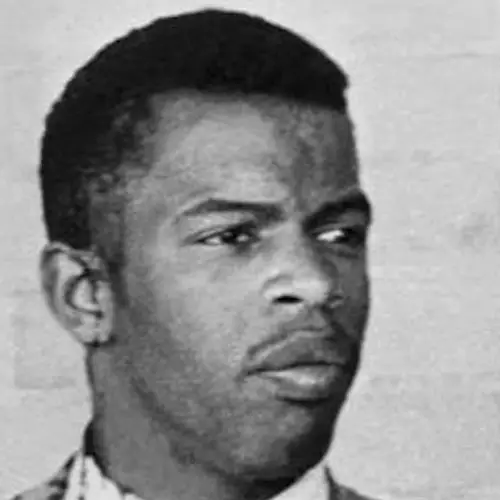

On May 9, John Lewis, who was black, and Albert Bigelow, who was white, entered a Greyhound bus station in Rock Hill, South Carolina labeled "whites only."

In the first major act of resistance the Riders faced, Lewis — who is now a U.S. congressman from Georgia — was promptly beaten and bloodied by a white man. The man busted his lip open and cut his face, and the brutal beating made the news.

"All along the way we saw these signs that said white waiting, colored waiting, white men, colored men, white women, colored women," Lewis recounted of the dangerous trip. "Segregation was the order of the day."

Equality for African-Americans would never be won easily that much was certain, but the violence against them had only just begun. The attacks they endured in Anniston, Alabama shocked the nation.

On May 14, a mob of angry white segregationists blocked one of the Freedom Riders' buses, attacking it with rocks, bricks and firebombs.

They chanted "Burn them alive!" and "Fry the goddamn n—!" while slashing the bus's tires. Even when the bus erupted in smoke and flames, mobsters blocked the door so the passengers couldn't leave.

Luckily, the arrival and warning shots from state troopers pushed the racist mob away. But just a few hours later, more black and white Riders were beaten after entering the whites-only restaurants and waiting rooms at the bus terminals in Anniston and Birmingham.

Despite the bloody attacks, many of the volunteers persevered and were adamant in continuing their Freedom Ride through the Deep South.

"We were determined not to let any act of violence keep us from our goal," Lewis said. "We knew our lives could be threatened, but we had made up our minds not to turn back."

Robert F. Kennedy Orders Military Convoy For Riders

Getty ImagesA mob of anti-integrationists as seen through a window of a Freedom Riders' bus.

The attacks on the Freedom Riders in Alabama left many of them bruised and injured: a white Rider named Jim Peck suffered severe injuries after he was beaten, and received 56 stitches to his head.

Diane Nash, the chairperson of the Student Nonviolent Coordination Committee (SNCC) behind the famous Nashville sit-ins, took over the responsibilities for the Freedom Ride and recruited ten of her own members to pick up the mission and continue the ride to Jackson, Mississippi.

The physical attacks against the Freedom Riders had caught enough press attention that it finally reached the White House. At the head of the U.S. Justice Department that time was Robert F. Kennedy, the brother of then-President John F. Kennedy.

The violence that erupted in Alabama was enough for the attorney general to order his second-in-command, John Seigenthaler, to get in touch with Nash. The government wanted the activists to stop the campaign, going as far as offering the activists money in exchange for halting the Freedom Rides.

Activists knew that without strong enforcement and support from the federal government, things were never going to change, not even under Attorney General Kennedy.

"Everywhere but Alabama, and Mississippi, and Georgia," historian Raymond Arsenault noted. At that time, the Kennedy brothers still depended on the Democratic votes from the south.

"We had made it that far without their money, so I wanted to stay independent. The Kennedys were in the executive branch of government, and it was their job to enforce the law," Nash told the press decades later.

"If they had done their job we wouldn’t have to have been risking our lives."

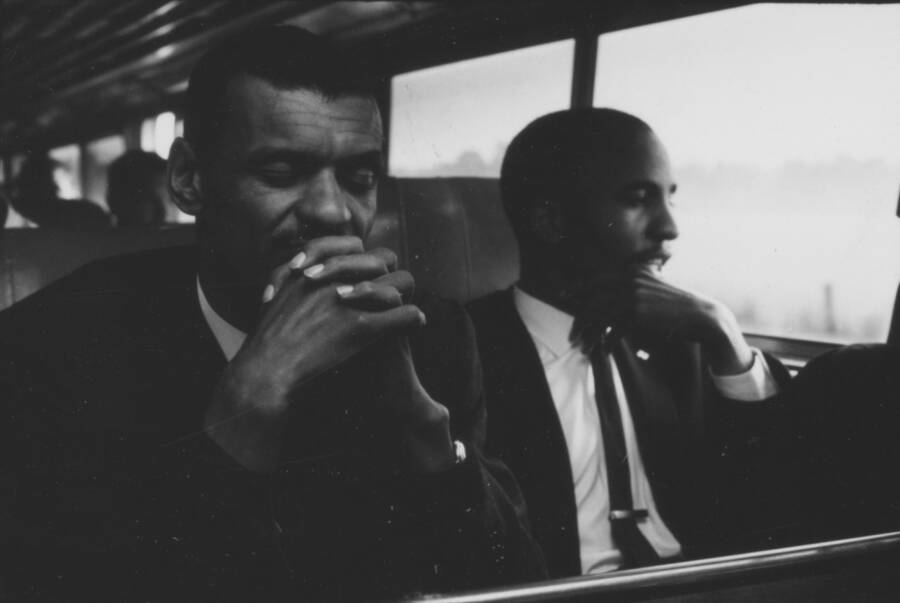

Southbound

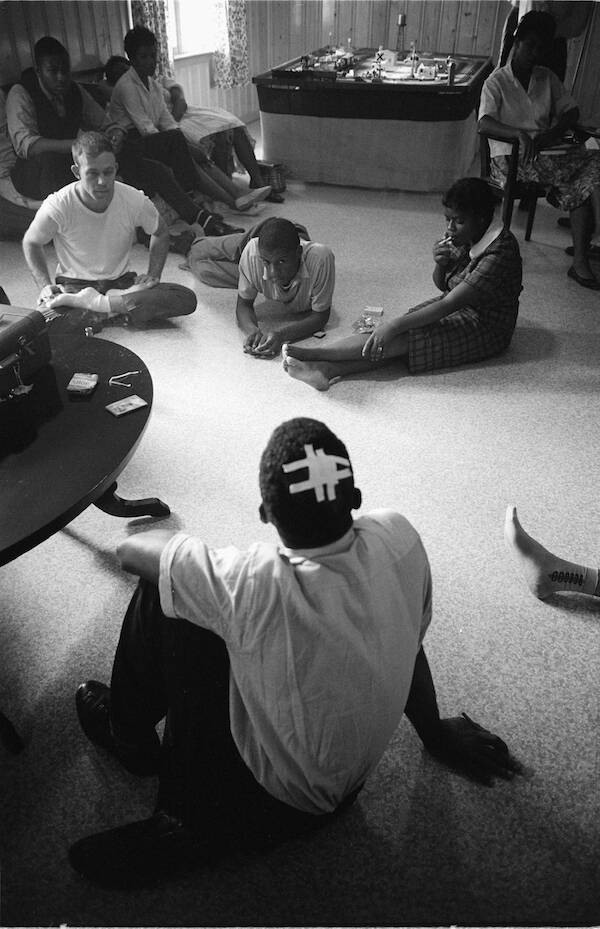

The Freedom Riders continued to Montgomery, Alabama, and stopped for a secret mass meeting at the local First Baptist Church, led by Rev. Ralph Abernathy. King greeted the activists, rallying them to continue their journey through the state.

The Freedom Riders disguised themselves as members of the church choir and managed to blend in with the local churchgoers. But word soon got out of the Freedom Riders' presence and an angry white mob slowly formed around the church. King personally called the attorney general to ask for protection for the Freedom Riders to prevent more bloodshed.

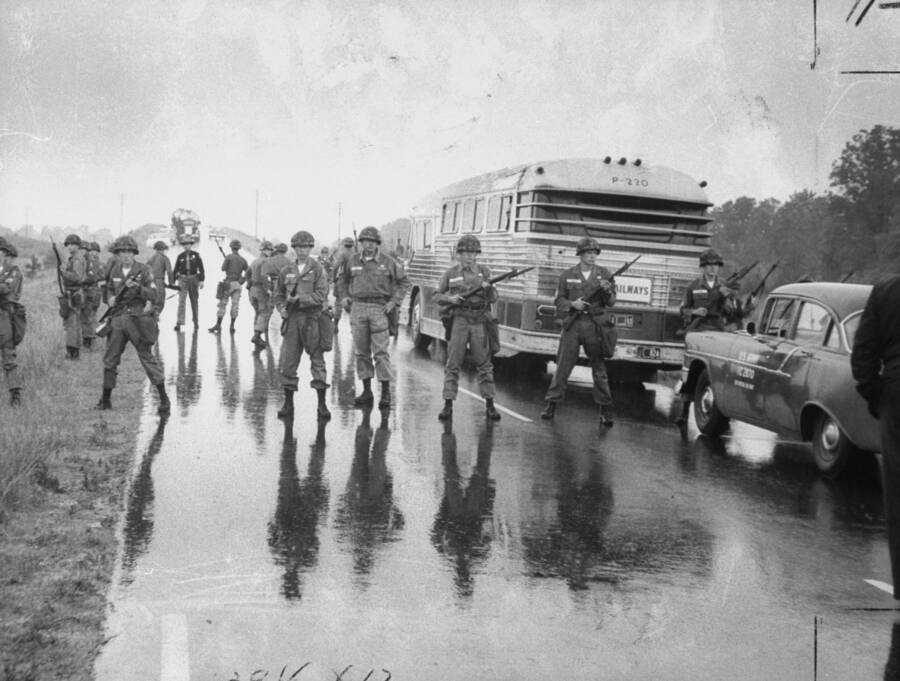

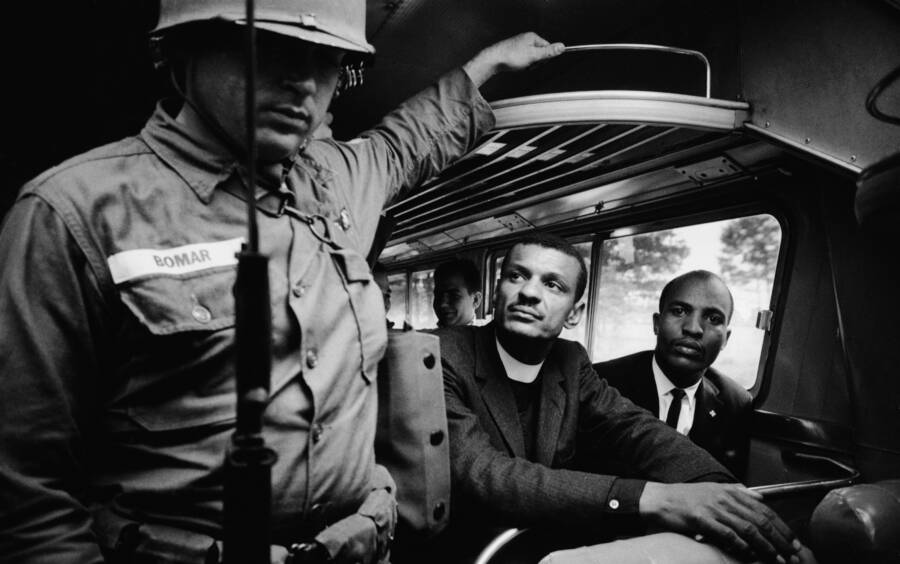

The government issued a presidential order to have the National Guard sent to Montgomery and escort the Freedom Riders on the rest of their journey to Jackson, Mississippi.

Notably, even after decades of atrocities faced by blacks in the South at the hands of the KKK and state and local administrations, the federal government wasn't compelled to act until white civil rights activists — not just black ones — faced violence and angry mobs.

Former Freedom Rider Peter Ackerberg, who joined the ride in Montgomery, said that while he'd always talked a "big radical game," he had never acted on his convictions before joining the Riders.

"What am I going to tell my children when they ask me about this time?" Ackerberg remembers thinking. "I was pretty scared... The black guys and girls were singing.... They were so spirited and so unafraid. They were really prepared to risk their lives."

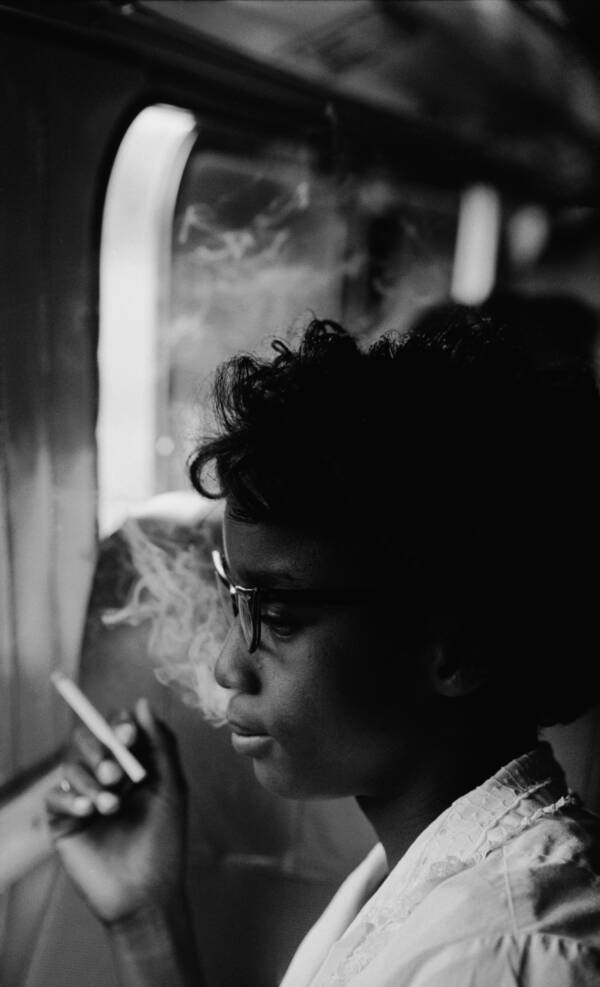

One of the best-known anthems that has become emblematic of the civil rights movement — even outside the U.S. — was the song "We Shall Overcome," which was also adopted as the go-to anthem among black and white Freedom Riders singing on the bus.

Locked Up In Jackson

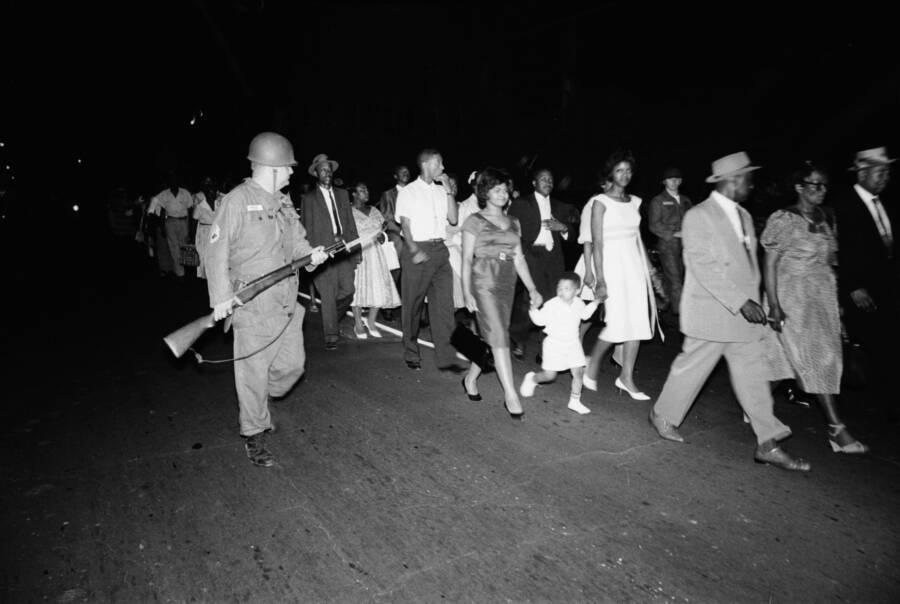

Paul Schutzer/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty ImagesFreedom Riders were assigned a convoy of National Guards to protect the activists from being attacked by pro-segregationists.

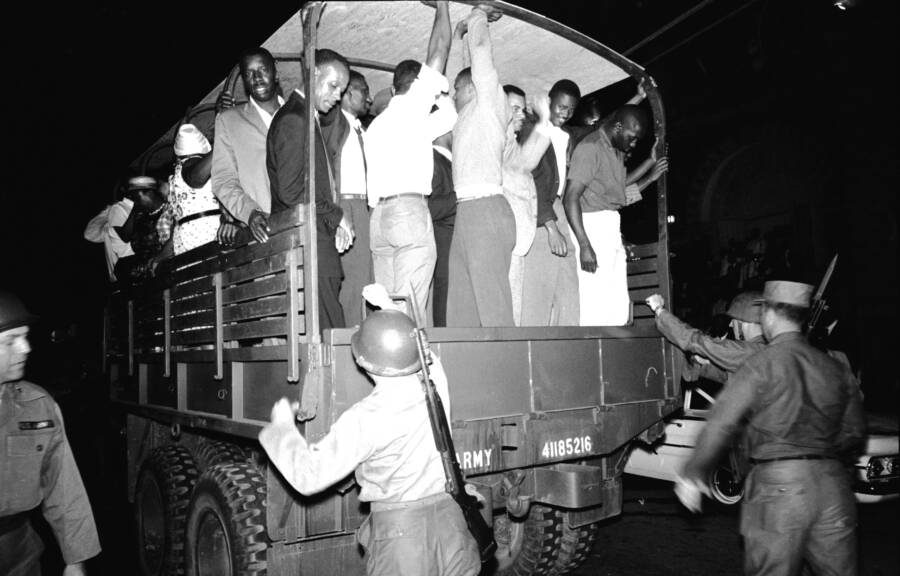

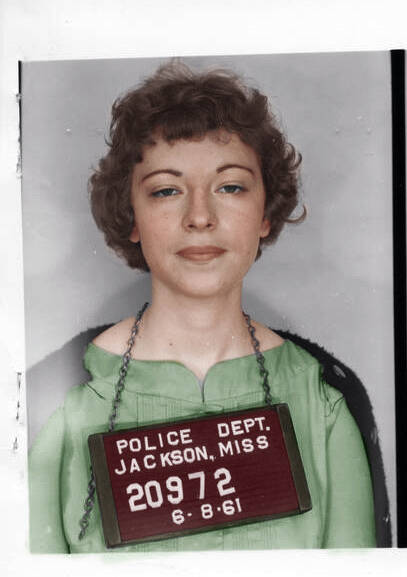

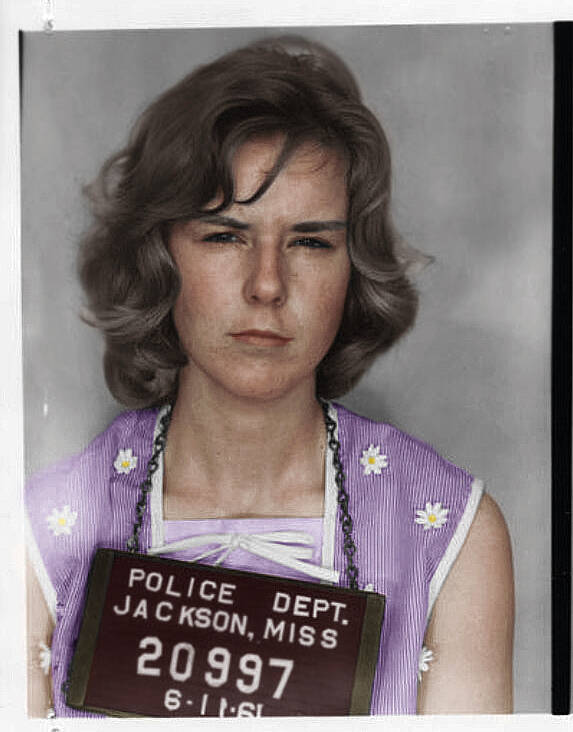

When Freedom Riders finally arrived at the Jackson, Mississippi bus station, 306 of them were arrested by the police for "breach of peace" after they refused to stay out of white restrooms and facilities. White Freedom Riders were also arrested after deliberately using facilities meant for black passengers only.

Many of them were locked up in Parchman, Mississippi's worst prison, for weeks, where they endured appalling treatment and conditions; some of them were slapped or beaten for not addressing the prison guards as "sir".

"The dehumanizing process started as soon as we got there," said former Freedom Rider Hank Thomas, who was then a sophomore at Howard University.

"We were told to strip naked and then walked down this long corridor....I'll never forget [CORE Director] Jim Farmer, a very dignified man...walking down this long corridor naked....That is dehumanizing. And that was the whole point."

Finally, after many more Freedom Ride protests throughout the segregated South in the ensuing months, Robert Kennedy issued an official petition to enforce regulations against segregated bus facilities. As a result, the Interstate Commerce Commission enacted tougher regulations and revved up reinforcement of the segregation ban in November 1961. The new laws were enforced by fines of up to $500 (or more than $4,000 in today's dollars).

To this day, the Freedom Riders movement continues to be a beacon of societal change and the principles of pursuing justice, no matter what the cost may be.

In fact, in 2009, just after President Barack Obama became the first black president of the United States, the man who beat Rep. John Lewis senseless 48 years prior, went to Washington D.C. and apologized to Lewis.

"It was wrong for people to be like I was," said Elwin Wilson, who died in 2013. "But I am not that man anymore."

"I forgive you," Lewis said. "It is good to see you, my friend."

After learning about how the Freedom Riders risked their lives to push for greater enforcement of desegregation laws, take a look at 55 powerful photos that relive the civil rights movement. Then, read about four female civil rights leaders you didn't learn about in school.