Matthew Henson was part of the historic 1909 Arctic expedition that reached the North Pole, but because he had accompanied a white explorer, he wasn't recognized for his feat until decades later.

Many have laid claim to being the first human to set foot in the Arctic. But few of them have as strong a claim to the title as Matthew Henson — an orphaned descendant of slaves with a thirst for adventure.

Henson and the white explorer Robert E. Peary attempted to reach the Arctic Circle seven times before they succeeded in 1909, and Henson claims he was the first of their crew to reach the historic point. Yet, his incredible achievement went largely ignored for decades because of the color of his skin.

Matthew Henson Was Born A Seafarer

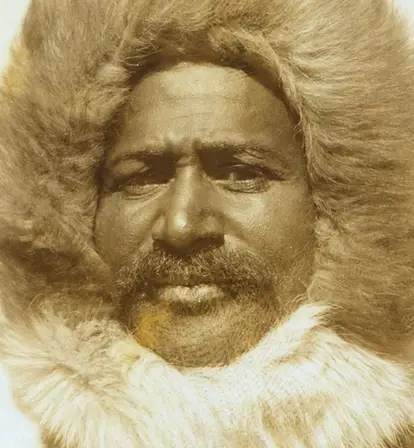

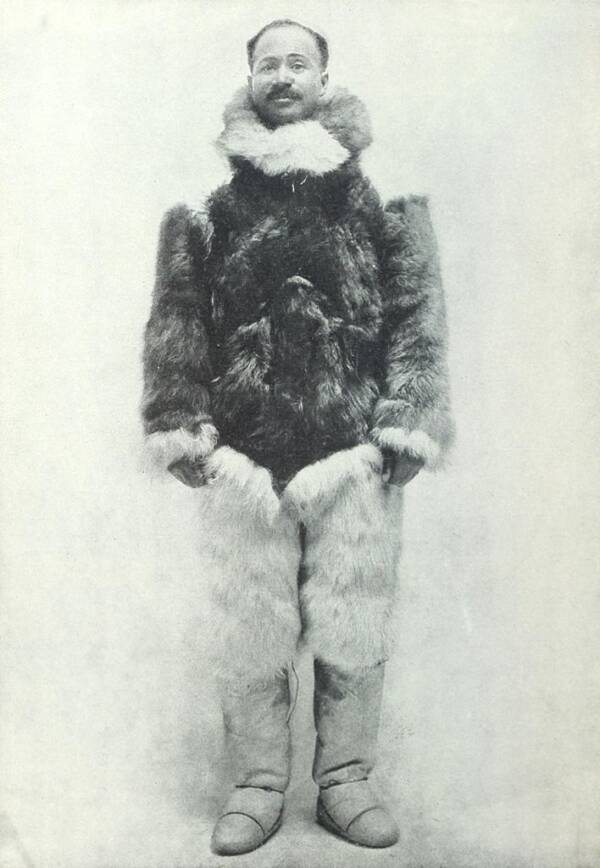

Getty ImagesMatthew Henson may have been the first African American to set foot in the North Pole.

Matthew Henson led a remarkably adventurous life even before he became one of the first men to reach the North Pole.

Henson was born in Maryland on Aug. 8, 1866, a year after the U.S. Civil War had ended. A descendant of slaves, his parents worked as sharecroppers in the post-Civil War years but later died during his childhood. He moved to Washington, D.C., to live with his uncle and at 12, lured by his fascination of stories from local seamen, Henson found work as a cabin boy on the merchant ship Katie Hines.

For the next six or so years, Henson lived a seaman himself, traversing unknown waters. He learned how to read and write while on the high seas and picked up valuable seafaring skills like navigation.

“The lure of the Arctic is tugging at my heart. To me the trail is calling! The old trail. The trail that is always new.”

Matthew Henson returned to Washington, D.C. where he spent time working on dry land. But in 1887, he fortuitously met Commander Robert E. Peary, a civil engineer and explorer with a commission by the U.S. Navy to survey Nicaragua.

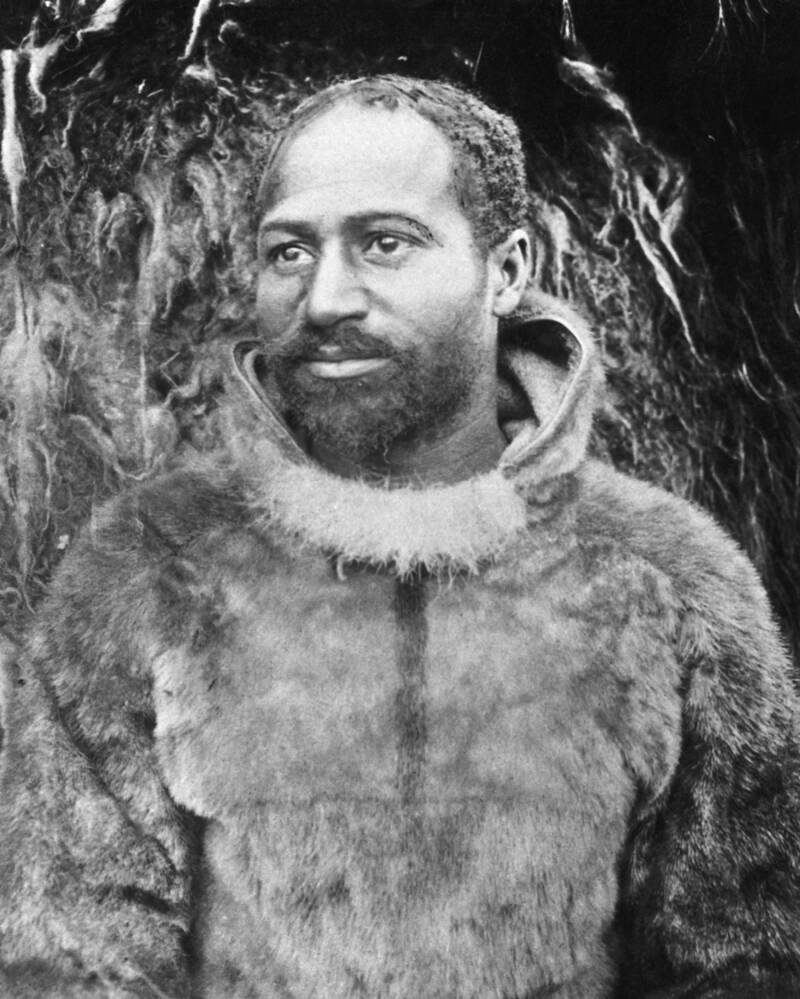

Wikimedia CommonsHe was recruited by Commander Robert Peary for an expedition to Nicaragua in 1877, their first trip together.

Peary had executed a handful of successful expeditions around the world by this point. Upon learning of Henson’s seafaring experience, Peary hired him to be a valet for his upcoming trip. It would be the first of many expeditions between them.

The Race To The North Pole

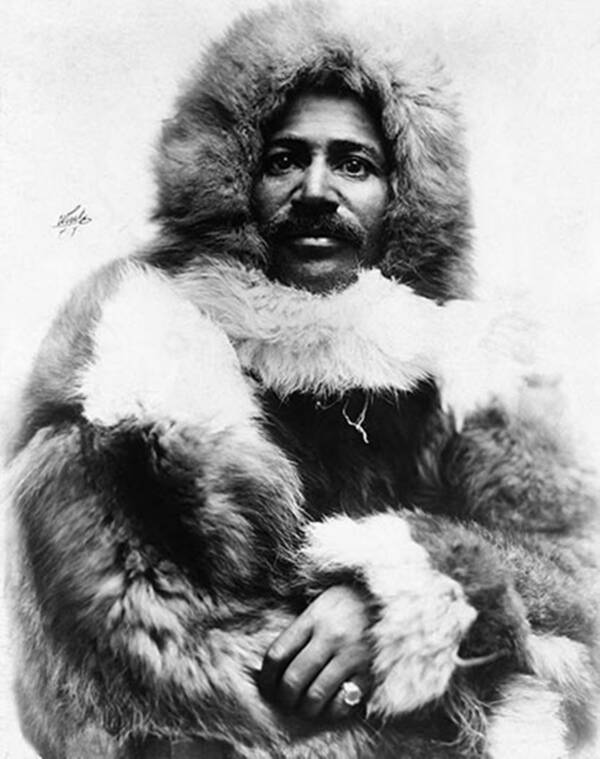

Donald and Miriam MacMillan via Bowdoin CollegeMatthew Henson was popular with members of the crew he traveled with and Indigenous peoples he met along the way.

Together with Peary, Henson explored the world. Peary possessed ample resources to fund their international expeditions through a group of rich sponsors known as the Peary Arctic Club. These men paid for Peary’s trips in exchange for having their names placed on his site maps.

Peary was among the last of the “imperialistic explorers” of an earlier age, who were white explorers that traipsed the globe for money and fame with little regard for the native people and cultures they encountered.

Matthew Henson, meanwhile, became a valuable asset to Peary’s travels. According to Henson’s own 1912 memoir, he easily integrated into the local Inuit culture in the Arctic. He could drive a sled like a native and even spoke the native language. “I have come to love these people,” Henson wrote. “They are my friends and regard me as theirs.” On the final page of his memoir, Henson recorded all 218 names of the Inuit from Smith Sound on Canada’s Ellesemere Island.

He went on to accompany Peary on seven Arctic expeditions between 1891 and 1909.

Peary and Henson’s most famous trip by far was their 1909 expedition to the Arctic which allegedly ended in their reaching the elusive North Pole, a feat that hundreds of explorers before them had failed to do over the course of three centuries. Some even lost their lives in their attempts.

Donald and Miriam MacMillan via Bowdoin CollegeHenson first began his global travels as a young man working as a deckhand.

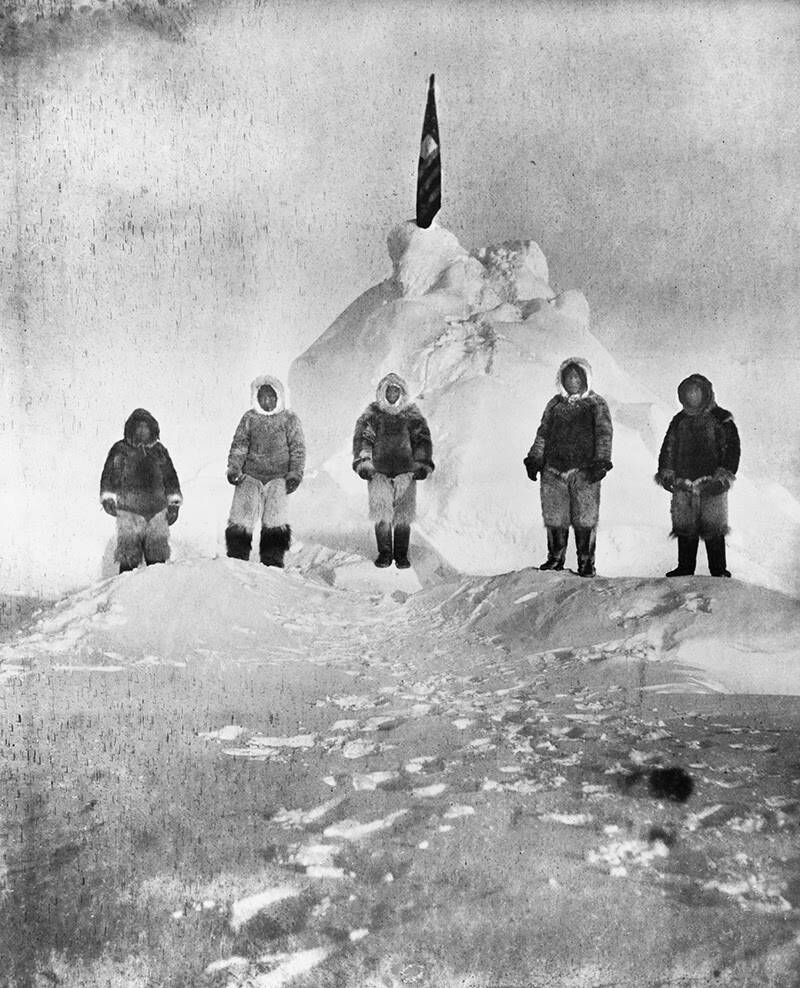

In his subsequent book, A Negro Explorer at the North Pole, Matthew Henson vividly recounted his journey alongside Peary and a 50-man crew that included four Inuit guides: Seegloo, Ootah, Egingwah and Ooqueeah, toward the North Pole.

According to Henson’s account, when the group was about 134 miles away from the North Pole, Peary, Henson and the four Inuit guides broke off from the rest of the crew and continued on their own. It was a strategy Peary favored because it kept his men and supplies staggered across terrain. He called it the “Peary system.”

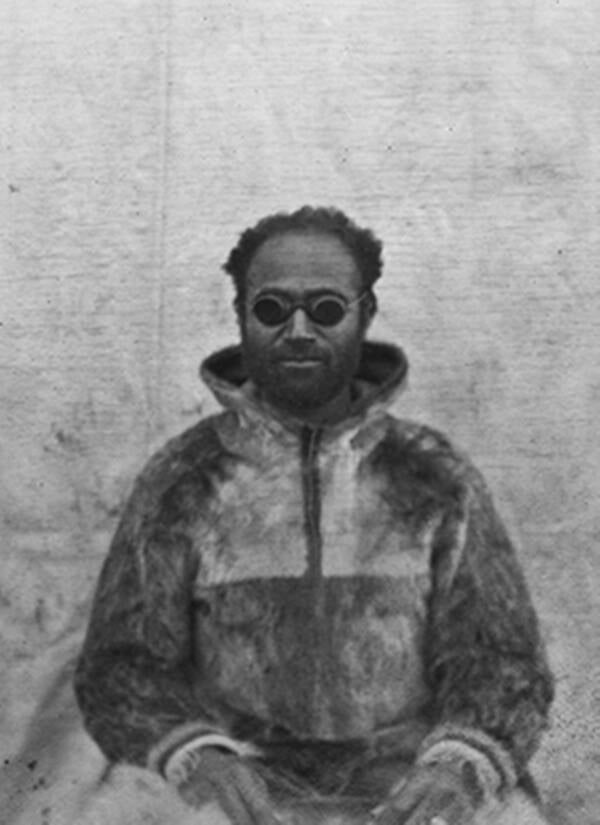

National Archives and Records Administration via Bowdoin CollegeHenson in goggles. His friendship with Robert Peary soured after they returned from their trip to the North Pole.

A few days later, on April 6, 1909, Henson had a “feeling” that the group had reached their destination. Henson later told the Boston American that he voiced his instinct to Peary, asking, “We are now at the Pole, are we not?”

To which Peary replied, “I do not suppose that we can swear that we are exactly at the Pole.”

Nonetheless, the men celebrated. Peary stuck an American flag on top of an igloo their Inuit guides had built. Then, they turned in for the night before returning to their basecamp at the village of Annoatok.

Was Henson Really The First Man To Reach The North Pole?

Wikimedia CommonsThe announcement of their North Pole ‘discovery’ was on the front page of The New York Times in 1909.

News of Matthew Henson and Peary’s arrival at the North Pole made the front page of The New York Times on September 7 of that year under the headline: “Peary Discovers the North Pole After Eight Trials in 23 Years.”

Due to the so-called Peary system, Henson had been trekking ahead of the group and thus claimed to have been the very first to set foot at the North Pole.

However, whether Henson and Peary really did make it all the way to the North Pole was and remains difficult to verify. Unlike the South Pole, the North Pole is a drifting piece of ice. Navigations would point South and with other ice masses present it was impossible to pinpoint the exact location of the North Pole. Navigational instruments and techniques weren’t sophisticated enough yet to counter this issue.

Wikimedia CommonsMatthew Henson poses with the four Indigenous guides who accompanied him to the North Pole: Seegloo, Ootah, Egingwah, and Ooqueeah.

It didn’t help that just a week earlier, the explorer Frederick A. Cook claimed to have “discovered” the North Pole, according, at least, to the New York Herald. The story put Cook’s arrival at the North Pole in April 1908 — a full year before Matthew Henson’s group claimed to have arrived there.

The contradicting claims spurred a public frenzy and a U.S. Congressional inquiry. The inquiry never recognized Peary’s crew as the first to reach the North Pole due to a lack of supplemental information. Cook was subjected to a smear campaign by Peary’s well-connected colleagues, so the public largely recognized Peary as the first man to reach the pole.

Despite all the hullabaloo around their feat, Henson’s name was largely kept out of the papers and he was not recognized for the enormous role he played in bringing their crew across the Arctic. Consequently, Henson’s friendship with Peary quickly soured.

Henson, who was deprived of the recognition awarded to Peary for their historic trip, began touring and giving lectures about the expedition as a way to earn a living.

But in 1988, the National Geographic Society determined Peary likely missed the North Pole by 30 to 60 miles. Henson’s book had claimed Peary checked their location using a sextant, though he never told Henson the results.

While their team may have not been the first ones to reach the North Pole, Matthew Henson was likely still the first African American to set foot in the territory.

“He was the most popular man aboard the ship with the Eskimos,” wrote explorer Donald MacMillan, who ventured alongside Henson and Peary. Henson was fluent in the native tongue of the Inughuit tribe, had impeccable navigation skills, and was handy with building sledges and stoves.

“Henson, the colored man, went to the Pole with Peary because he was a better man than any of his white assistants,” MacMillan continued, “As Peary himself admitted, ‘I can’t get along without Henson.'”

Matthew Henson Finally Receives His Due

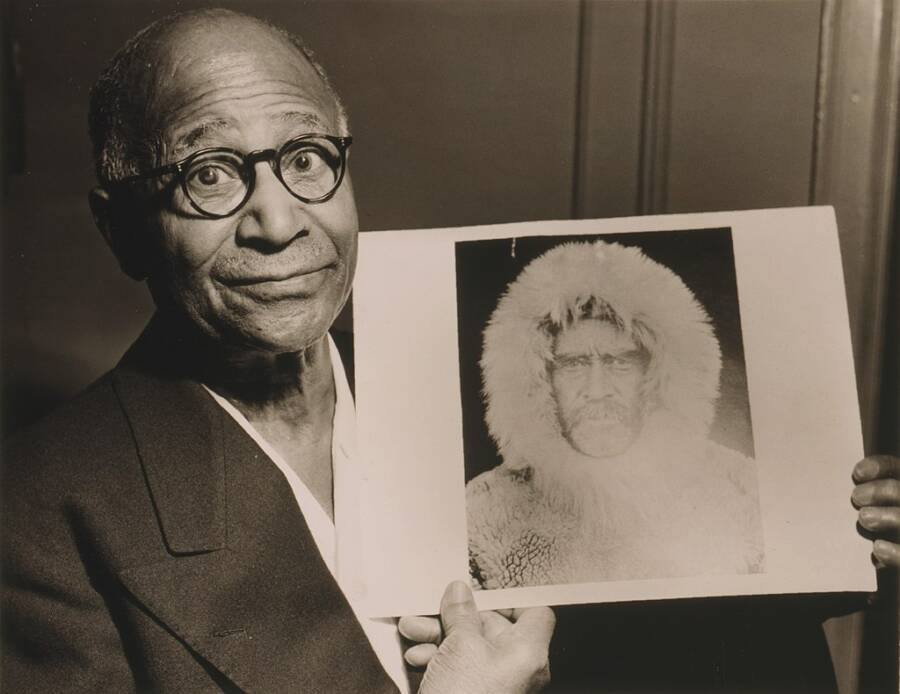

Wikimedia CommonsHenson, in his old age, holds a photo of Peary. His body was reinterred at Arlington National Cemetery in 1988.

Henson received a slew of belated honors in his later years while working as a clerk U.S. Customs. He was admitted to the elite Explorers Club and awarded the Peary Polar Expedition Medal by Congress — nearly 40 years after his famous expedition. He was also invited as a guest of honor to the White House by Presidents Harry S. Truman and Dwight D. Eisenhower.

After his death in 1955, Matthew Henson was buried at the Woodlawn Cemetery in New York, but his and his wife’s bodies were later moved to Arlington National Cemetery after an exception was made by President Ronald Reagan following the request of S. Allen Counter of Harvard University, an expert on Henson’s biography.

Though Henson married twice, he had only one son named Ahnahkaq Henson who he fathered with his Inuit lover. Henson’s grave was later visited by his son.

In 1988, Henson was posthumously awarded the Hubbard Medal, the highest honor bestowed by the National Geographic Society, perhaps his most prestigious honor yet.

Whether Henson was the first man to reach the pole remains in contention. As journalist Lincoln Steffens wrote, “Whatever the truth is, the situation is as wonderful as the Pole… And whatever they found there, those explorers, they have left there a story as great as a continent.”

Next, meet Zheng He, Medieval China’s legendary Muslim explorer. Then, learn about Fridtjof Nansen, the Nobel-winning humanitarian who was the first man to cross Greenland.