Death By Elephant: One Of The Most Brutal Medieval Execution Methods

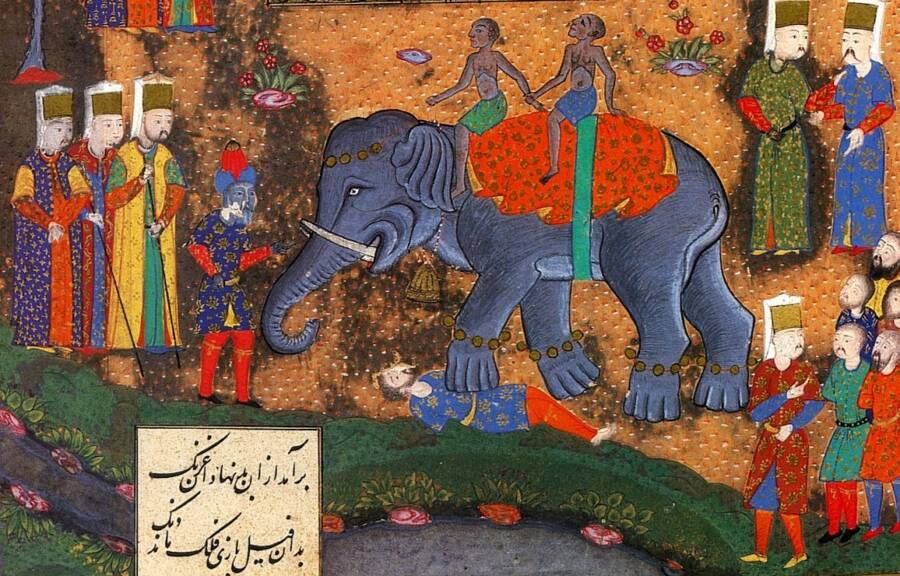

Wikimedia CommonsPrisoners of war being executed by elephant near Belgrade in the 1500s.

For millennia, elephants have been wrangled and trained by humans to accomplish all sorts of things. From assisting armies to helping people cross mountains, elephants have been reliably commandeered to great effect. These colossal creatures even helped construct the legendary Cambodian temple complex, Angkor Wat, in the 12th century.

While elephants are revered in Buddhist and Hindu faiths to this day, their specific use as Medieval executioners remains lesser known. Although capital punishment in the Middle Ages was unilaterally cruel, death by elephant almost seems too gruesome to be real.

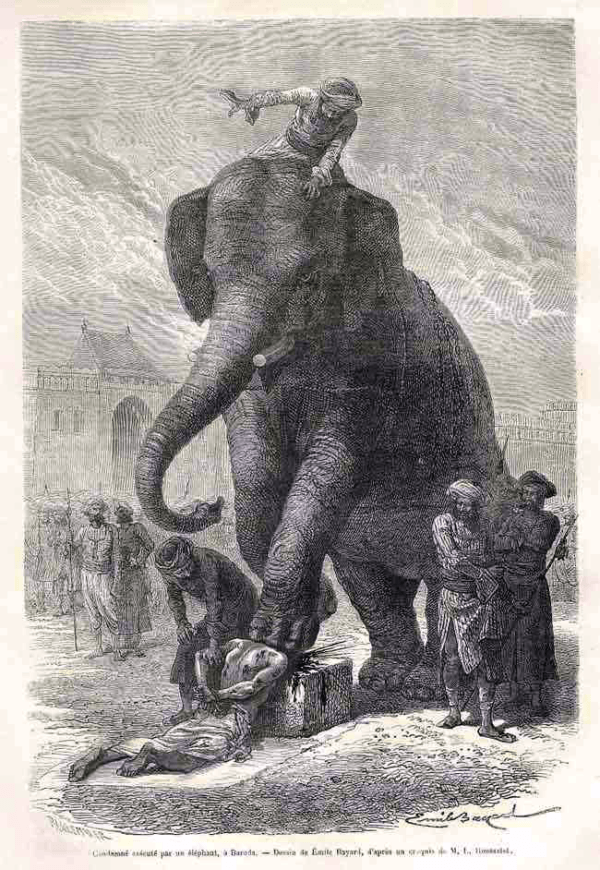

Wikimedia CommonsA Medieval execution described by French traveler Louis Rousselet 1868’s Le Tour du Monde.

Most commonly used in Southeast Asia, death by elephant was known as gunga rao in India. Standardized in the Middle Ages, this Medieval execution method occasionally found its way to the Western world and only saw a decline in popularity in the 19th century.

Typically, death by elephant was relegated to enemy soldiers or civilians who committed crimes like tax evasion and theft. As one might expect, these executions relied on the brute force of an elephant to crush a victim, usually by pressing on their head or abdomen with a foot. However, sometimes executioners came up with more creative approaches.

For example, one Delhi sultanate turned the deaths of prisoners into a public spectacle, where elephants were trained to cut people open with “pointed blades fitted to their tusks.”

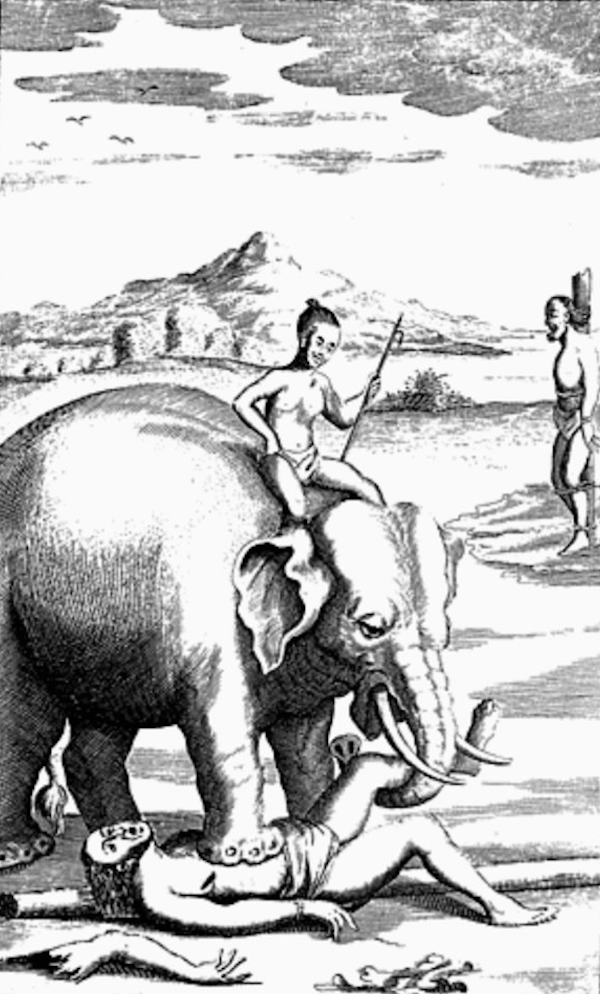

Wikimedia CommonsA 1681 illustration of a condemned prisoner being killed by an elephant in Sri Lanka.

Unlike tigers and lions, elephants aren’t naturally inclined to kill human beings, but they can be trained to do so. And perhaps even more chillingly, they can be trained to torture people in specific ways before killing them. For example, the elephant might break a criminal’s limbs before doling out a fatal blow to the skull. This was often used to demonstrate a ruler’s control.

This Medieval execution method wasn’t exclusive to the Middle Ages and was practiced for centuries in many countries, including India, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam. Death by elephant continued until the late 19th century, when the practice apparently came to an end.