The Apollo Moon landings were unbelievable -- so much so that around 10 million Americans actually don't believe they happened. Why?

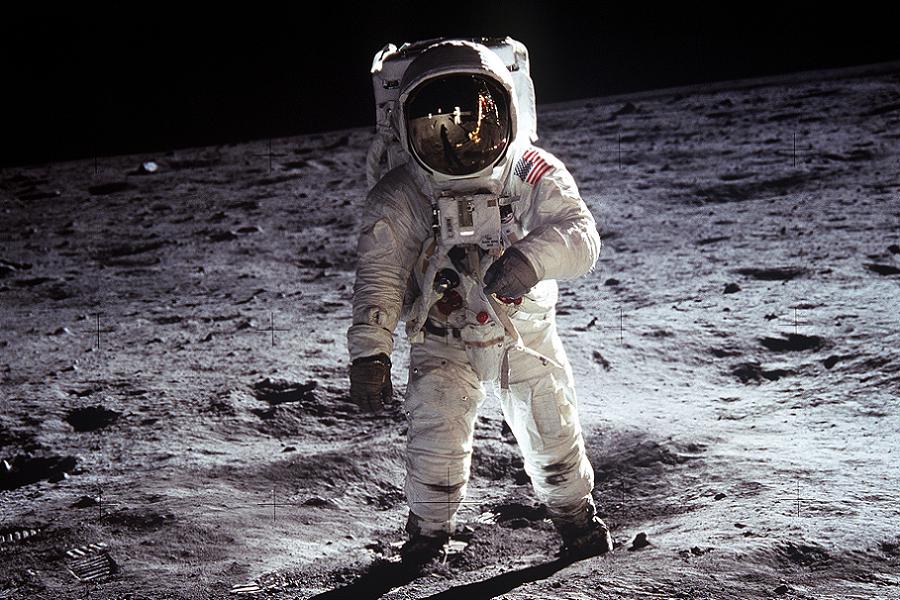

Wikimedia CommonsBuzz Aldrin walks on the moon, July 20, 1969.

July 20 marks the anniversary of the first Moon landing, and – unlike most anniversaries – it’s something to celebrate. Just to get started, engineers had to build a 40-story tower and pack it with a quarter of a million gallons of explosives that somehow didn’t just blow up on the launchpad.

Once NASA engineers finished triggering the controlled explosion of the biggest conventional bomb ever built, the three men sitting on top of it hurtled through the instant death of space for three days before gently touching down right about where they planned.

The mission profile was so tightly planned that lunar lander Neil Armstrong only had about six seconds of fuel left when the craft set down.

It was a truly unbelievable feat — which might explain why in 2013 Public Policy Polling found that seven percent of American voters believe the whole thing was a fake.

That’s nearly 10 million people. Who are they and what do they believe really happened? Perhaps more important, why do the believe what they do?

The Conspiracy

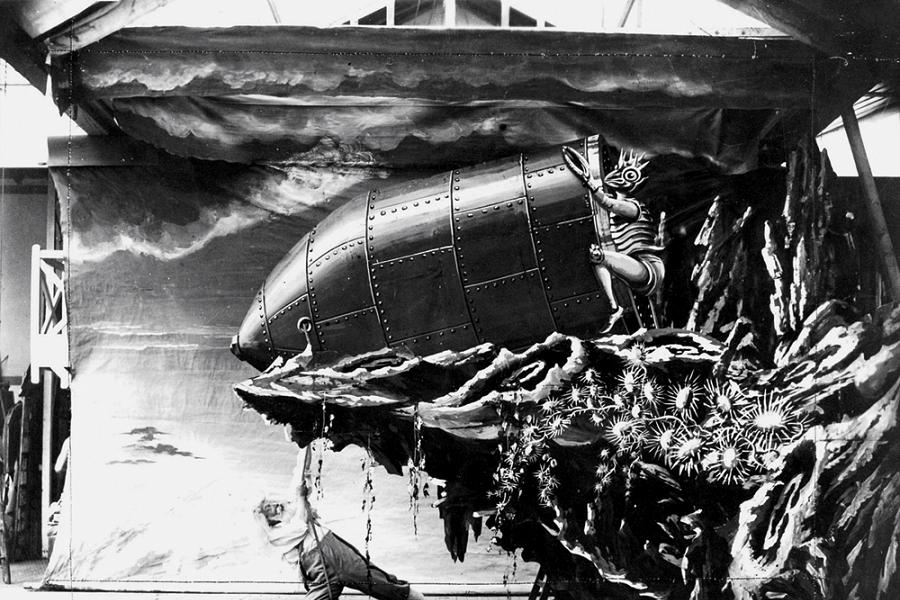

Wikimedia CommonsA production still from A Trip to the Moon, a 1902 French film depicting the lunar journey of several astronomers.

It’s sometime in the late 1960s. NASA has been working overtime for years to fulfill President Kennedy’s call for a manned mission to the Moon, but the project is plagued by engineering challenges.

By about 1966 or 1967, with delays and three fatalities threatening to hobble the Apollo Project for good, somebody near the top of the space agency realizes the lunar mission just isn’t possible.

However, given the high political stakes of the project, America can’t simply give up. So a mysterious “They” make a terrible decision: scrap the launch and hire mysterious Hollywood director Stanley Kubrick to fake evidence of success.

By July 20, 1969, everything is in place, the footage is ready to go, and NASA launches a dummy rocket from the Kennedy Space Center only to flip over and crash into the Atlantic Ocean.

For the next week or so, three men pretending to be astronauts send “broadcasts” back to Mission Control in Houston, where editors prepare pre-shot footage for public consumption. An airplane later carries the three men out to the Pacific Ocean in a capsule and drops them in the water for a “rescue.”

For the next 47 years (and counting), nobody involved with the conspiracy ever utters a peep. Nobody confesses on their deathbed, nobody tells a clumsy lie and gets caught, and nobody who can prove they were a NASA employee ever writes a book or goes to the press. The secret is sealed and the masses go on believing the big lie forever.

An Appealing Worldview

Imgur/Bones4

Yes, everyone believes the big lie — except for a few clever people who know the real truth. Those 10 million or so people who think they know what really happened tend the sacred flame of truth in coffeehouses, Internet chat forums, and private email lists that disseminate the facts nobody else will talk about.

Self-published books purporting to have been written by NASA engineers, whose names the authors say were deleted from government employment records and Ivy League attendance rolls alike, educate these people about the biggest government-perpetrated hoax in the years between the Roswell crash and global warming. These people, they say, can see through the lies our government tells, and they privately know a terrible truth.

The appeal of this kind of thinking is obvious. Not only does it make the conspiracy theorist much smarter than 99 percent of the world, it also makes him or her a hero for debunking pernicious government lies.

But psychologists studying conspiracy theories over the decades have deepened the picture. They have found that the biggest single predictor for whether a person believes that NASA faked the Moon landings is a preexisting belief in one or more other conspiracy theories, usually relating to JFK’s death, global warming, or UFOs.

In other words, these are largely the same people, and the specific conspiracy they believe largely owes to circumstance, rather than evidence. Apart from a willingness to accept extraordinary claims, researchers write that conspiracy believers often demonstrate the following traits:

Narcissism: Clinical narcissism refers to some people’s tendency to view the world strictly from their own perspective, rather than picturing it from others’ points of view.

We all do this to some extent, but typical conspiracy theorists see the world as an amalgam of evil authorities, gullible suckers who’ve bought the lie, and the chosen few who have it all figured out. That’s according to research done by Michael J. Wood et. al. of the University of Kent, who found that people with a lot of narcissistic traits and low self-esteem were particularly at-risk for conspiratorial thinking.

Nonconformist politics: Believing your government lies is an inherently anti-establishment position, so it isn’t surprising that conspiracy theorists rarely support established authorities.

This is mainly a matter of temperament – people who call themselves politically liberal are more likely to believe in conspiracies involving “evil” corporations and “oppressive” police authorities, such as the various assassinations of the ’60s, while politically conservative theorists cultivate suspicion of scientific and political authorities, as is the case with denial of, say, global warming or evolution.

The Moon landing hoax is special in that it appeals to both sides: Liberals see the evil of the Cold War politics and defense contractors, while conservatives see the rottenness of the government and the lies of the NASA rocket scientists.

Tribalism: Most people who eventually accept fringe beliefs do so because someone they trust talked them into it. Having rejected established authorities, potential conspiracy believers form an attachment to non-establishment “experts” whose authority goes unquestioned. The sense of community that exists between people who carry a forbidden truth with them is enormous, and the sense that the world is against them only strengthens this connection.

Illogical thinking: Irrational habits of thought separate the true conspiracy theorist from mere eccentrics. The defining characteristic of a conspiracy theory is that it cannot be falsified. Unlike a real scientific theory, which fits conclusions to meet the facts, a conspiracy theory twists the fact to match the conclusion.

According to the University of Kent’s study, conspiracy theories form a belief system all their own, which are self-contained and very hard to break into. From the paper:

“The present research shows that even mutually incompatible conspiracy theories are positively correlated in endorsement. In Study 1. . . the more participants believed that Princess Diana faked her own death, the more they believed that she was murdered. In Study 2. . . the more participants believed that Osama Bin Laden was already dead when U.S. special forces raided his compound in Pakistan, the more they believed he is still alive. . . mutually incompatible conspiracy theories are positively associated because both are associated with the view that the authorities are engaged in a cover-up.”

This kind of close reasoning acts as a kind of immune system for conspiratorial belief systems. No matter what evidence is brought, and the evidence for the success of the Moon landings is immense, theorists can either ignore it or twist it into “proof” that the conspiracy is real.

Eventually, the conspiracy theorist has to believe in such a complicated nest of mutually contradicting “facts” that the simpler explanation is just that we went to the Moon, but that conclusion must be rejected for emotional reasons that have nothing to do with reality.

Add to this a strong Dunning-Kruger Effect, in which people with defective thinking habits are by definition the least able to spot where their thinking has gone wrong, and you have all of the necessary elements for an irrational belief that can last a lifetime.

Broad Implications

Martha Soukup/Flickr

This kind of broken thinking poses a problem for society, as conspiracy researcher Alfred Moore points out. According to Moore, conspiratorial thinking erodes society in at least five ways:

Healthy skepticism of government claims is generally a good thing. Science positively thrives on skepticism; knowing that all claims will be checked helps keep scientists honest and makes them actually do the math.

Conspiracy theories aren’t healthy skepticism, however; they’re a credulous rejection of facts for reasons that have a lot more to do with the believer than with the subject.

In place of reality, an essentially irrational belief like the Moon landing hoax substitutes a funhouse-mirror picture of the world that drives otherwise normal people away from the mainstream and encourages tribalism, short-term thinking, and a retreat into agreeable echo chambers on the Internet.

If we’re not careful, these traits will cause serious problems for us in the next century.

Next, read about the conspiracy theories that actually were true, and why chemtrails are a myth.