With mounting tensions between Italians and the rest of New Orleans', all it took was a murdered police chief to send the city into a mob frenzy.

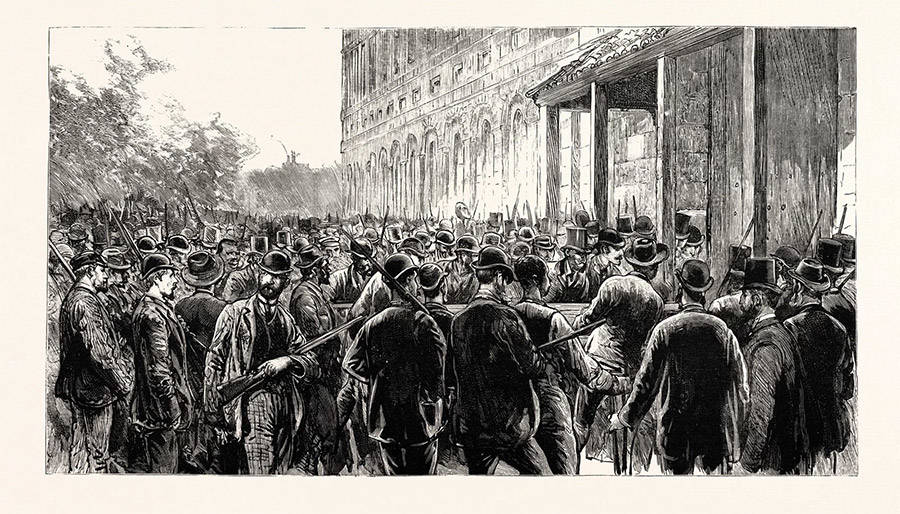

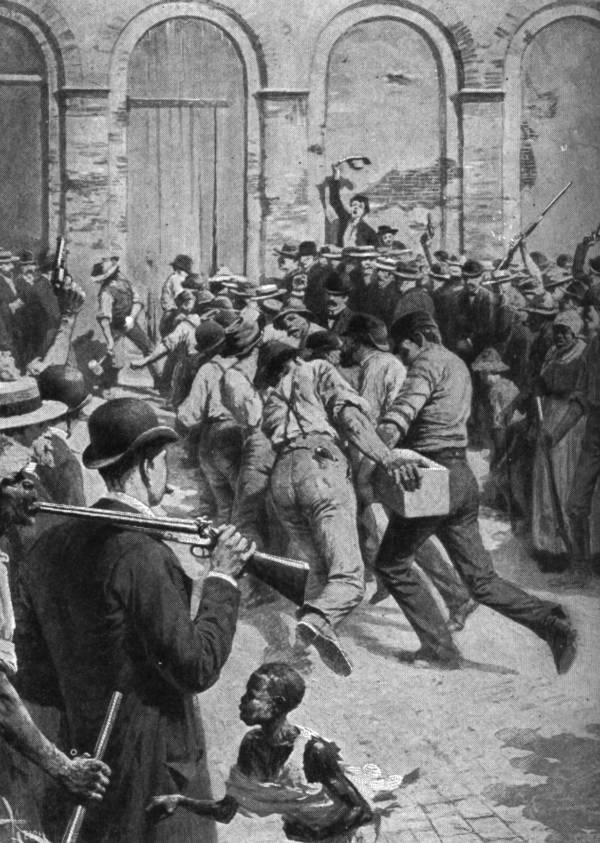

Universal History Archive/UIG/Getty ImagesThe New Orleans’ lynchers breaking into the prison.

In the mid-nineteenth century, Sicilian peasants began to leave Italy’s countryside in search of opportunity and wealth.

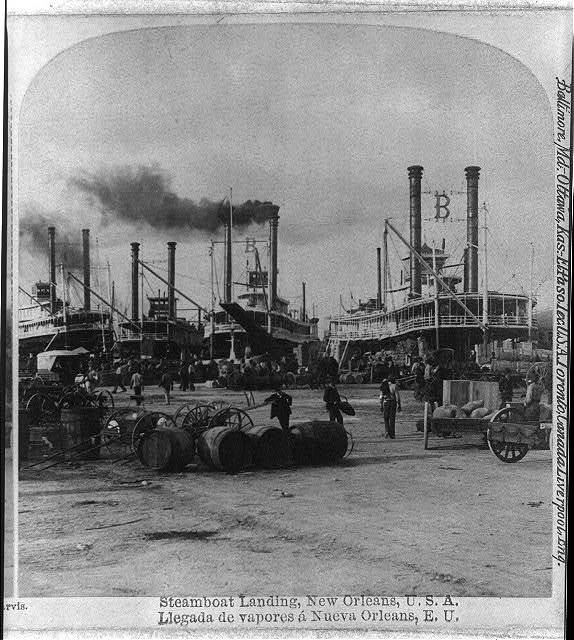

Immigration was stoked in part because the reunification of Italy resulted in their impoverishment — the new Italian government taxed the peasants so heavily that the poor were left no option but to starve or flee. By the end of the nineteenth century, over four million Italians had immigrated to the United States and a significant population settled in New Orleans as they could work in the booming industry of sugar and cotton.

Sicilians quickly grew to become one-tenth of the population in New Orleans, with the French quarter even becoming known as “Little Palermo.” By 1890, Italians owned or controlled more than 3,000 wholesale and retail businesses in the city.

However, the success of this industrious immigrant group threatened the authority of the old-line establishment.

Library of CongressA view of the docks where Italian immigrants would find work. 1891.

The majority of Sicilians kept to themselves as they planned to return to their native land. Unfortunately, this led to a keen distrust of Italians among the ruling whites. At this time, newspapers capitalized on this xenophobia by sensationalizing any stories involving Italians and crime.

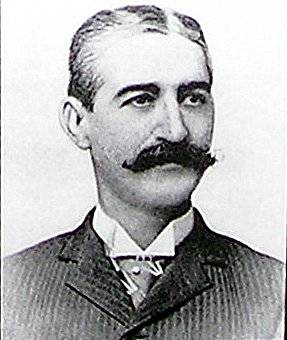

Tensions in New Orleans reached a fever pitch when David C. Hennessy, New Orleans’ Chief of Police, was murdered.

The Assassination Of David C. Hennessy

Wikimedia CommonsPortrait of David C. Hennessy.

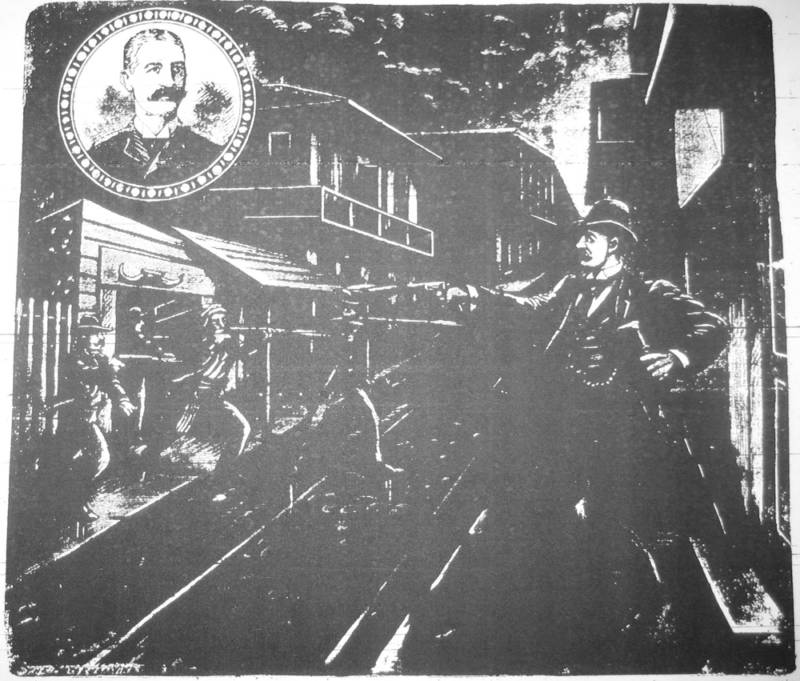

On the rainy night of Oct. 15, 1890, David Hennessy and Captain William O’Connor were leaving the Central Police Station. Hennessy turned toward Basin street, heading back to the home that he shared with his widowed mother. O’Connor walked in the opposite direction toward 273 Girod street in uptown New Orleans. The captain rarely walked home alone and for the past three years, he had done so in the company of bodyguards. However, on that fateful night, he walked by himself.

As Hennessy loped toward his doorstep, a group of men leaped out from the darkness and opened fire at the chief. One of the bullets pierced his liver and settled in his chest; another shattered his right leg. Hennessy returned fire but he was already mortally wounded. O’Connor heard the gunshots and ran to Hennessy’s side.

The dying police chief lamented to his friend, “Oh Billy, Billy. They have given it to me and I gave them back the best way I could.” O’Connor asked his dearest friend, “Who did this, Dave?”

Hennessy famously replied: “The Dagoes.”

Wikimedia CommonsArtist’s conception of Hennessy’s murder.

However, Hennessy did not perish quickly. In fact, the hardened police chief believed that he was going to survive. When his mother rushed to see her wounded son at Charity Hospital, he told her, “I’ll be home by and by.” But his colleagues still sent for a priest and within a matter of hours, the chief was dead. Mourners clustered outside the hospital and when Hennessy’s body was transported to his home, more grievers gathered.

Hennessy’s funeral was an enormous and grand affair. Mourners arrived at the crack of dawn and more people lined up around the block by 10 a.m. In all, thousands came to mourn the fallen police chief.

The New York Times even reported on the magnitude of the funeral:

“All day long the people crowded into the City Hall to view the body and it was almost impossible to reach the bier, which had been placed in the same room in which the body of Jefferson Davis lay in state…The carriage moved through principal streets of the city, all of which were so crowded with people as to blockade the street cars and passage of vehicles.”

Although Hennessy had been unable to identify his assailants and O’Connor had arrived after they escaped, the words Hennessy had whispered to O’Connor told Mayor Joseph Shakspeare all he needed to know. At a city council meeting shortly after, Shakspeare declared, “We must teach these people a lesson that they will not forget by all time.”

David C. Hennessy’s assassination was not entirely surprising, given that he had a reputation for being tough on crime, especially on Italian crime. Hennessy was a favorite for city reformers and his death triggered public outcry.

Newspapers swiftly condemned the chief of police’s murder as a “declaration of war,” calling it an “Italian assassination.” The mayor ordered a dragnet of the city and sent the police into the French Quarter. Over two hundred and fifty Italian men were dragged into custody. Nineteen were charged with murder.

Over the next four months, the press gave a large amount of credibility to the theory that these men belonged to a secret society of Italians known as the mafia. The word mafia began to pop up in newspapers across the nation, reinforcing the stereotype of Italians being associated with organized crime.

The Mob Takes Over

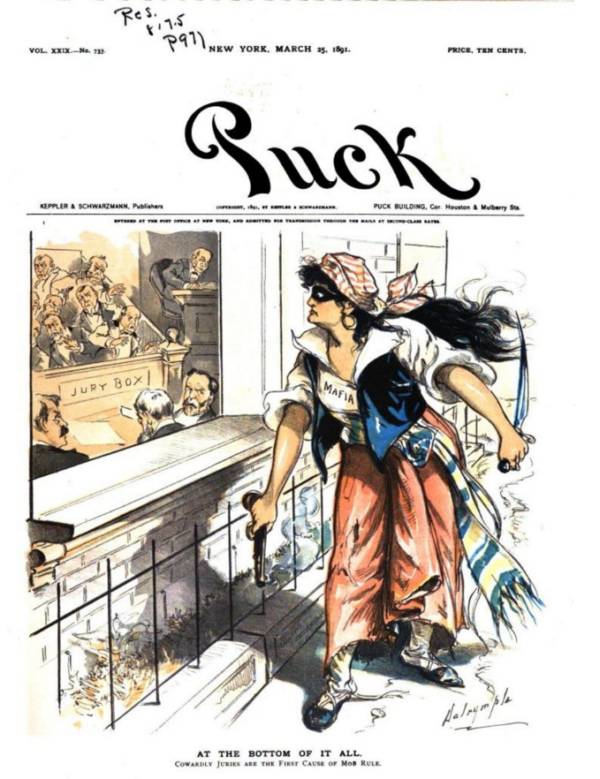

Wikimedia CommonsA caricature by Puck on March 25, 1891. The Italian mafia is threatening the jury.

On Feb. 28, 1891, the verdict of the sensational Hennessy trial read not guilty. For a city that had been led to believe that these men were indeed guilty, it was a tremendous shock. The very next day, a public call to action was published in the daily paper.

John C. Wickliffe, one of the speakers at this city meeting, cried out, “On the spirit of our forefathers; like when we cleared out the carpetbaggers before, we will go to the Parish prison and clear out these Sicilian mafia thugs.”

The crowd then turned from an outraged public into a vengeful mob, as many shouted, “Yes! Yes, hang the dagoes!”

Over ten thousand people gathered and made their way through Congo Square on North Rampart Street to the Old Parish Prison at Basin and Treme Streets. Hearing the pounding steps and cries of the crowd, Capt. Lemuel Davis, warden of the prison, readied his men.

Wikimedia CommonsPeople rushing into the prison, trying to break the gate.

Out of the crowd emerged an advance guard with shotguns and rifles, numbering at three hundred men. These men immediately headed down to the main entrance and demanded that they be let in. When they were flat out denied, the crowd started hammering the entrance gate with axes, crowbars, and picks. The guard told the Italian prisoners to hide, but the mob quickly found them. The men that were immediately spotted were riddled with bullets.

The rabid crowd then dragged several men from the prison and carried them through the streets, where they were hung from the lampposts. Other men were hung from the great oak tree, where they would be later used as target practice.

After the mass lynching had ended, the city declared that order had been restored. On the front page of the New York Times, it read, “Chief Hennessy Avenged.”

As for the lynch mob, it was decided that the crowd, “embraced several thousand of the first, best and even the most law-abiding citizens of the city…in fact, the act seemed to involve the entire people of the parish and the City of New Orleans.”

No further action was ever taken for the multiple counts of murder. In addition, the New Orleans’ lynchings had a severe effect on the Italian community as a whole.

The case not only pushed stereotypes of Italian gangsters and introduced the term “Mafia” to the American public, but it forced Italy to cut off diplomatic relations with the U.S. and even sparked rumors of a war.

Next, read about the Chinese Massacre of 1871, another case of mass lynchings in the U.S. Then read about how “Little Caesar” Salvatore Maranzano created the American Mafia.