Project Odeuropa hopes to document, recreate, and store the smells of old Europe in an accessible online library.

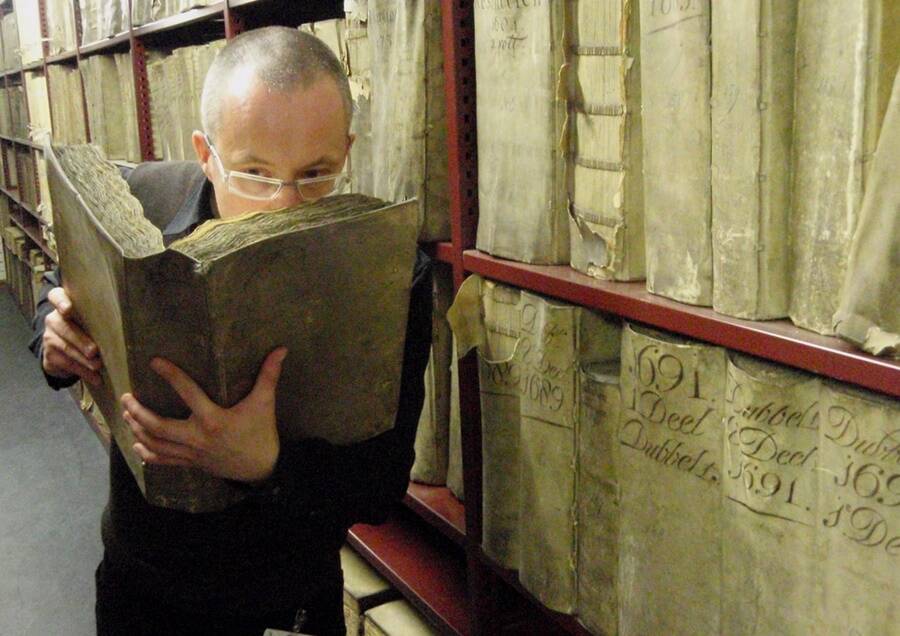

Matija Strlic/OdeuropaThe project hopes that museums will use these scents for their exhibits.

If they had to guess, scientists think historic Europe may have smelled like tobacco or experimental plague remedies. And now, they are working to identify more of these smells and archive them in a digital library.

According to the The Guardian, a team of European scientists from various fields, including artificial intelligence, have banded together to work on an ambitious project called “Odeuropa.”

Their primary objective is to identify certain odors reminiscent of Europe between the 16th and early 20th centuries, document them, make them accessible to the public online, and then potentially employ them at various museums.

But in order to determine what exactly each period of Europe smelled like, researchers will first have to focus on developing artificial intelligence that can identify descriptions of smells and images of aromatic items in more than 250,000 documents written in seven different languages.

Then, that information will be used to create an online encyclopedia of “European odors” alongside contextual descriptions about them.

OdeuropaThe study will employ historians, scientists, and artificial intelligence.

“Once you start looking at printed texts published in Europe since 1500, you will find loads of references to smell, from religious scents – like the smell of incense – through to things like tobacco,” said William Tullett of Anglia Ruskin University in Cambridge and a member of the Odeuropa team.

“That could take us into all kinds of different scents, whether that is the use of herbs like rosemary to protect against plague, [or] the use of smelling salts in the 18th and 19th centuries as an antidote to fits and fainting,” explained Tullett, who wrote the book Smell in Eighteenth-Century England.

Indeed, 17th-century London likely reeked of plague remedies like burning rosemary or tar.

Wikimedia CommonsThe smell of tobacco, which has a long history within the colonial European trade, is one prevalent smell.

The researchers hope that in identifying scents that appeared to be the most common in Europe between the 16th and 20th centuries, they can then map how the meaning and use of those odors have evolved over time.

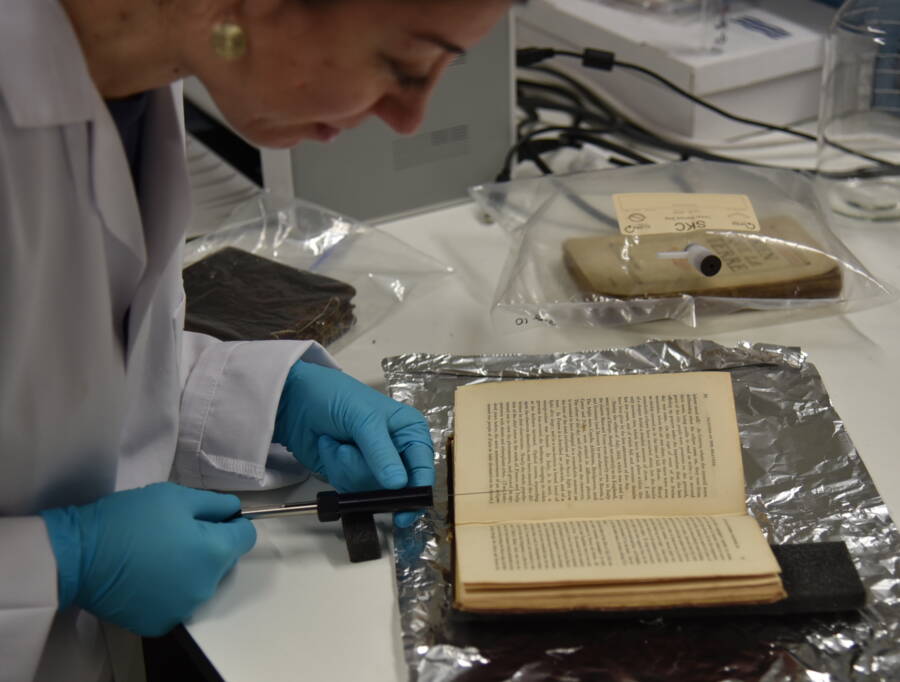

“Old smells, or smells of objects, tell us a lot about how those objects degrade, how they can be preserved, and also how those smells can be conserved,” said team member Matija Strlič of London’s University College.

For example, tobacco, which has native origins in pre-colonial America, was an exotic and expensive commodity when it was first introduced in Europe in the late 15th century. But tobacco’s standing in European society changed in the following years as it became a ubiquitous trading commodity.

“It is a commodity that is introduced into Europe in the 16th century that starts off as being a very exotic kind of smell, but then quickly becomes domesticated and becomes part of the normal smell-scape of lots of European towns,” said Tullett. “Once we are getting into the 18th century, people are complaining actively about the use of tobacco in theatres.”

OdeuropaAfter identifying common smells, the researchers will then work with chemists and perfumists to recreate them.

In addition to gaining a deeper understanding of Europe’s past, the results of this multimillion-dollar research project could potentially help enhance one’s experience in a museum. The team plans to collaborate with chemists and perfume makers to recreate these distinct smells and attach them to museum exhibits.

The Jorvik Viking Centre in York, for instance, has done something like this before by recreating smells reminiscent of the 10th century in their exhibits.

“One of the things that the Jorvik Viking Centre demonstrates is that smell can have a real impact on the way people engage with museums,” said Tullett. “We are trying to encourage people to consider both the foul and the fragrant elements of Europe’s olfactory past.”

Next, take a look at the unusual foods that were commonly eaten in Medieval Europe. Then, read about this study, which found that the human tongue can actually smell.