Anatomist Gunther von Hagens invented the process of plastination with the idea being to preserve human tissue in ways never thought possible.

Plastination preserves human bodies in startling detail and with life-like results. The chemical process doesn’t change the human tissue whatsoever, and the flesh doesn’t degrade over time. Von Hagens’ idea is to use his technique for educational purposes towards the general public.

The painstaking process starts with traditional formaldehyde or other body-preserving chemicals. Scientists pump these chemicals through veins and arteries to kill any bacteria. Destroying the germs prevents degradation of the flesh. That injection process alone takes about three to four hours.

Then dissection starts, and this could take anywhere from 500 to 1,000 hours. Skin, fatty tissues, and connective tissue are removed to prepare individual organs for plastination.

pss/FlickrA body plastinated into a pose of a basketball player.

After dissection, the actual plastination begins. Water and any soluble fats remaining the body are dissolved in a bath of acetone. In subzero temperatures, acetone replaces the water in individual cells.

The next step is crucial to the plastination process. Over the course of two to five weeks, a body goes into a bath of a liquid polymer such as silicone rubber. This bath draws out the acetone, and every single cell remaining in the body then has the silicone rubber in it.

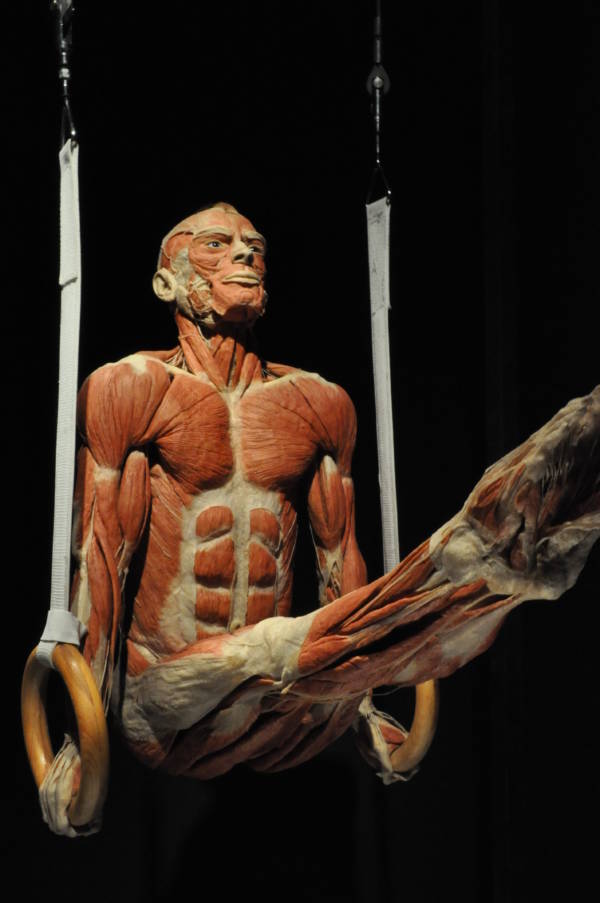

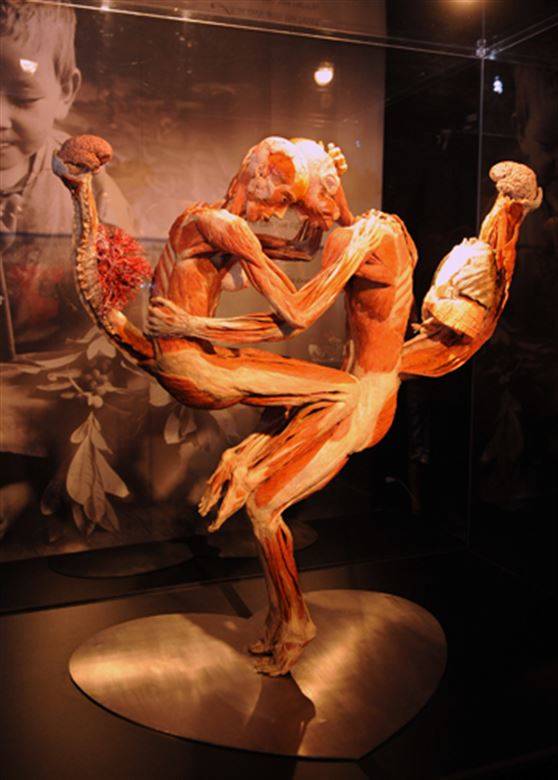

At this point, von Hagens and his team can position the body in whatever pose they desire. The team uses wires, clamps, hooks, and foam blocks to position the corpse. This can take weeks or months, and it depends on the aesthetic concerns of the donor’s wishes or what von Hagens’ team decides is most appropriate.

Wikimedia CommonsA human hand undergoes plastination.

Finally, each body goes through a hardening process. This happens with gas, light or heat depending on the polymer used to preserve the body. Plastination takes up to 1,500 hours of labor and a year to complete.

In 1995, von Hagens and his team took their plastination show on the road with the Bodyworlds traveling exhibition. The overall goal is to get people thinking about the limits of the human body, the meaning of life, and strengthening someone’s sense of health.

One remarkable pose showed someone riding on a plastinated horse. Other bodies show layers of muscle peeled back to reveal internal organs. Some poses show smiling, serene faces while others are contemplative and introspective. A few show people embracing one another as if they are friends or lovers.

Wikimedia CommonsA male gymnast does his rings routine.

Plastination, you could say, is the ultimate combination of life and art.

The popularity of von Hagens’ work took off since his traveling exhibitions went public. As many as 8,000 people are on a waiting list to have their bodies plastinated after they die. The only expense to the family is to have the body transported to an embalmer who works closely with von Hagens. Some people see plastination as less expensive than a funeral, while others seem to have a sense of usefulness.

Rather than a burial, a plastinated body can serve as an educational tool. Even medical schools are considering the use of plastinated bodies as real-life anatomy lessons instead of traditional cadavers.

Department of Defense/A couple, forever plastinated in a loving embrace.

Plastination wouldn’t replace hands-on dissection of cadavers. However, it would save money and resources over the long term for colleges and universities that teach basic anatomy as a medical course for aspiring doctors and nurses.

Plastination is a remarkable process that may even give humans a sense of immortality. Instead of visiting a loved one’s gravesite, imagine going to see that person in an art exhibition a year after they pass away.

Next, learn about the The Musée Fragonard, the original bodies exhibit that was created in 1766. Then read about real Frankenstein experiments and the mad scientists behind them.