Martin Luther King Jr. once called Chicago the most racist city in America. Here's the long history that proves him right.

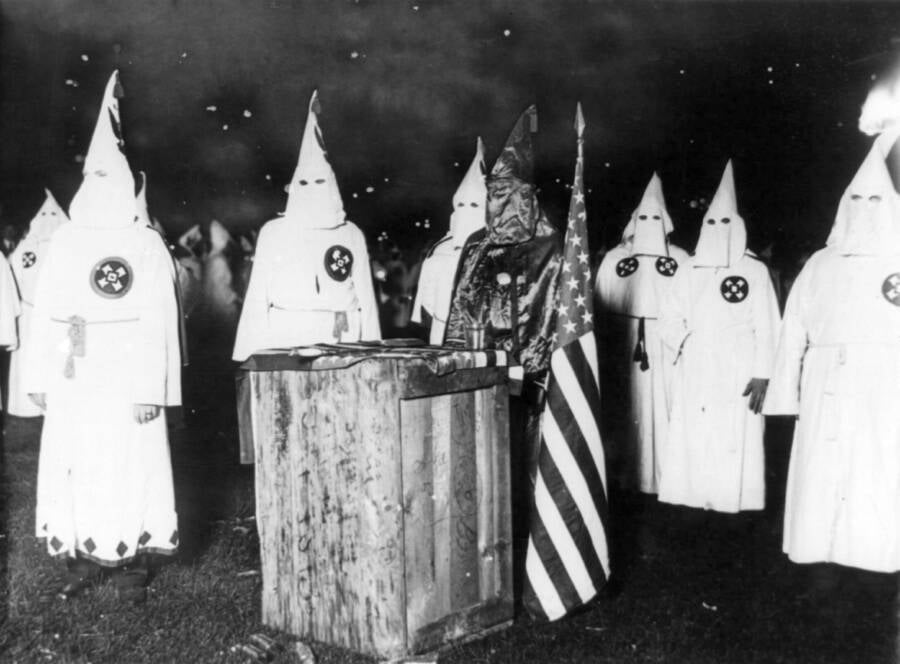

Underwood & Underwood/Library of CongressThe Ku Klux Klan holds a meeting with nearly 30,000 members from the Chicagoland area. Circa 1920.

In 1890, there were about 15,000 African Americans living in Chicago. From about 1916 to 1970, the Great Migration brought millions of African Americans from the rural South to the cities of the North, Midwest, and West. One of the most popular destinations was Chicago.

By 1970, about 1 million Black people called the Windy City their home — making up nearly one-third of Chicago’s total population. But Black Americans who migrated from the South soon realized that things were far from perfect in the North. From mob violence to segregation to hateful rallies, this is the long history of racism in Chicago.

The Great Migration And The Changing Demographics Of Chicago

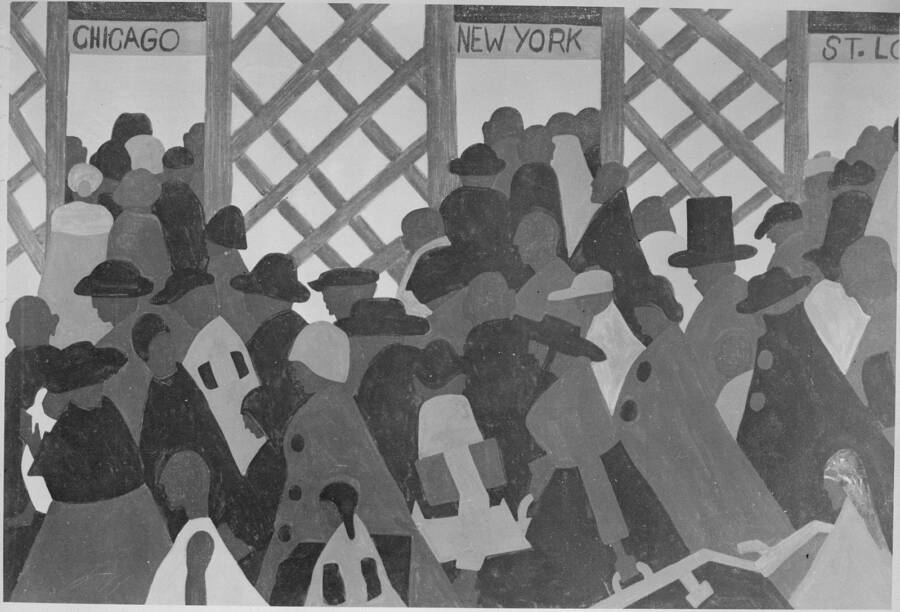

Jacob Lawrence/National Archives and Records Administration

Artist Jacob Lawrence’s painting, titled, “During the World War there was a great migration North by Southern Negroes.” 1941.

Over 6 million Black Americans left the South during the early and mid-20th century. So during the Great Migration, Chicago’s Black population skyrocketed.

Between 1915 and 1940, the city’s African American population more than doubled. In the decades following, the number continued to grow and grow. All told, more than 500,000 Black Southerners moved to Chicago throughout the Great Migration.

But what drove this Great Migration in the first place? One big factor was Jim Crow. In the South, the rise of Jim Crow restrictions essentially made Black people second-class citizens. So it’s no surprise why they would want to live in a place where they could hypothetically have more freedom.

Another factor was Chicago’s need for more workers. In the advent of World War I, an increasingly industrialized city needed as many workers as possible to keep the place running. And as foreign immigration rates plummeted around this time, African American workers stepped in.

Finally, Black Chicagoans encouraged Southerners to come to the North. The nation’s largest Black newspaper, the Chicago Defender, promoted a vision of prosperity for African Americans in the city. But this wave of migration quickly fueled tensions between Black and white communities in Chicago.

Unfortunately, for many families who moved north, Chicago was not an escape from discrimination. Instead of formal Jim Crow laws, the city simply enforced segregation in other ways.

The city often pushed Black residents into tenement housing. And even when they were able to find somewhat nicer homes, white residents violently attacked them.

The Chicago Riots And The Red Summer of 1919

The West Virginian

A mob of white men stone and beat a Black victim outside a home in Chicago during the 1919 race riot.

During the Red Summer of 1919, racial tensions boiled over in Chicago.

It all started on July 27, 1919, when Chicagoans flocked to the beaches of Lake Michigan to swim. At first, it seemed like any other summer day in the city. But when a Black teenager named Eugene Williams crossed an invisible color line located near 29th Street, white Chicagoans lashed out at him.

A group of white beachgoers hurled rocks at the teenager, causing him to drown. Williams’ death — and the refusal of white policemen to arrest his killers — attracted angry crowds at the beach. And it didn’t take long for more violence to erupt.

White mobs flooded the city’s Black neighborhoods, lighting homes on fire and attacking residents. Over the course of a week, 38 people died and over 500 sustained injuries — with Black Chicagoans making up a majority of the victims.

The Chicago race riot of 1919 also left 1,000 Black Chicagoans homeless after rioters torched their residences. While Chicago wasn’t the only city in America to experience racial violence during this so-called Red Summer, its riot was among the worst.

According to historian Isabel Wilkerson, “Thus riots would become to the North what lynchings were to the South, each a display of uncontained rage by put-upon people directed toward the scapegoats of their condition.”

The Ku Klux Klan In Chicago’s Roaring Twenties

New York Daily News Archive/Contributor/Getty ImagesRobed members of the Ku Klux Klan at a church in Chicago in the 1920s.

The gangsters weren’t the only ones calling the shots in 1920s Chicago. In 1922, the Chicago Ku Klux Klan claimed over 100,000 members, the largest Klan membership in any American city at the time. (Some experts estimate the number of members may have actually been somewhere between 40,000 to 80,000.)

In Chicago, the Klan had become mainstream — and it was not only accepted but celebrated. A coffee company took out an ad in the local Klan magazine, promising “Kuality, Koffee, and Kourtesy.”

In the 1920s, Chicago’s population included more than 1 million Catholics and 800,000 immigrants — both targets of the Klan’s ire. But it was the city’s 110,000 Black residents that remained at the top of the Klan’s hate list.

At the time, the Klan wielded political power in the state — and they were not afraid to say it. Charles Palmer, the Grand Dragon of the Illinois KKK, gleefully told the Chicago Daily Tribune in 1924, “We know we’re the balance of power in the state… We can control state elections and get what we want from state government.”

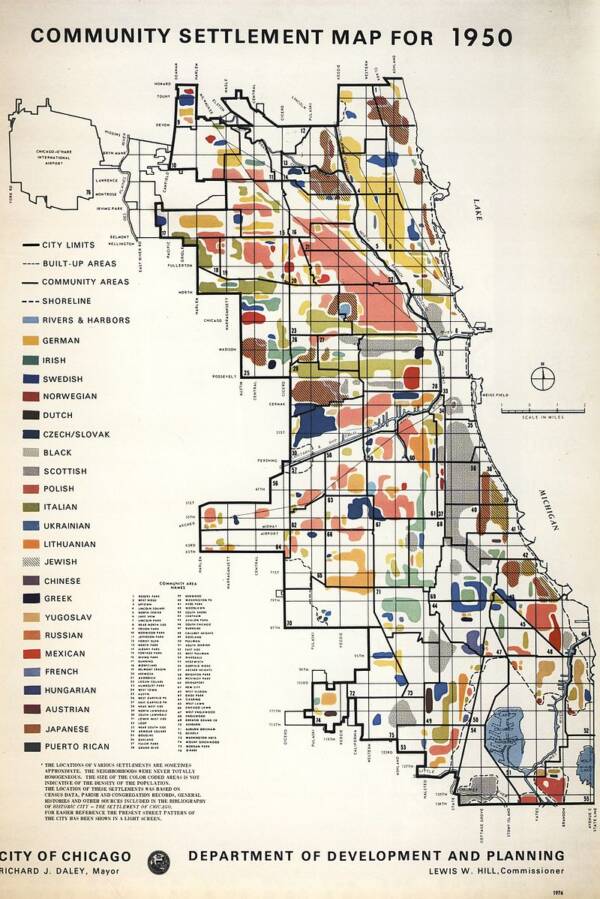

Segregation In Chicago’s Neighborhoods

City of Chicago Department of Planning and Development/Wikimedia Commons

By 1940, formal and informal policies had pushed Chicago’s Black residents into segregated neighborhoods.

In the early years of the Great Migration, white Chicagoans violently attacked Black homes — especially homes that were anywhere close to theirs.

From 1917 to 1921, white supremacists targeted Black families and the bankers and real estate agents who helped them find homes with 58 bombs. Jesse Binga, who founded Chicago’s first Black-owned bank, lived through six of those bombings.

These attacks, along with formal and informal policies, helped push Black Chicagoans into segregated neighborhoods. In the South Side neighborhood of Bronzeville, the population density hit double the city’s average by 1940 thanks to policies that forced Black Chicagoans into the area.

Author Richard Wright lived in one of those tiny apartments. “Sometimes five or six of us live in a one-room kitchenette,” Wright wrote. “The kitchenette is our prison, our death sentence without a trial, the new form of mob violence that assaults not only the lone individual, but all of us, in its ceaseless attacks.”

The Chicago Housing Authority (CHA), which was founded back in 1937, once attempted to integrate Chicago’s long segregated neighborhoods. The first CHA director, Elizabeth Wood, was in favor of maintaining diverse residences and even implemented a quota system in the hopes of bringing Black and white families together in one area.

In response, white Chicagoans once again attacked Black families who moved into their neighborhoods. In 1947, the CHA moved eight Black families into the previously all-white Fernwood Homes. And for at least three nights, white mobs rioted. It took more than 1,000 police officers to end the riot.

Meanwhile, widespread policies like redlining — a discriminatory practice of refusing loans, mortgages, and insurance to residents who lived in “risky” areas — made it difficult for Black Chicagoans to venture too far across the city or search for housing in the private market.

John White/U.S. National ArchivesStateway Gardens, a housing project on Chicago’s South Side, housed nearly 7,000 people in 1973.

A few years later, the CHA placed a light-skinned Black woman named Betty Howard in the previously all-white Trumbull Park Homes. Yet again, mobs targeted the facility with bricks, rocks, and explosives until her family required police escorts to leave.

The Cicero Riot saw even more violence. In July 1951, a Black World War II veteran named Harvey Clark Jr. tried to move his family of four from the South Side to the all-white suburb of Cicero.

But when the Clark family arrived, Cicero’s sheriff stepped in. “Get out of here fast,” the sheriff said. “There will be no moving into this building.”

Thanks to a court order, the Clarks were able to move into their new apartment. But they couldn’t even spend a single night there — due to the racist white mob numbering 4,000 that had gathered outside.

Even after the family fled, the white mob still wasn’t satisfied. They stormed the apartment, tore out the sinks, threw the furniture out the window, and smashed the piano. They then firebombed the entire building, leaving even the white tenants without a home.

A total of 118 men were arrested for rioting that night, but none of them were indicted. Instead, the agent and the owner of the apartment building were indicted for causing the riot — by renting to a Black family in the first place.

The Chicago Freedom Movement And The Backlash Against Civil Rights

The civil rights movement came to Chicago in 1966, when Martin Luther King, Jr. moved to the city’s West Side. “It is reasonable to believe that if the problems of Chicago, the nation’s second largest city, can be solved, they can be solved everywhere,” King declared.

His Chicago Freedom Movement targeted the city’s racist housing policies and its notorious slums. “We are here because we’re tired of living in rat-infested slums,” King announced in a speech at Soldier Field. “We are tired of being lynched physically in Mississippi, and we are tired of being lynched spiritually and economically in the North.”

But the civil rights leader soon found Chicago even more hostile toward his movement than some places in the Deep South.

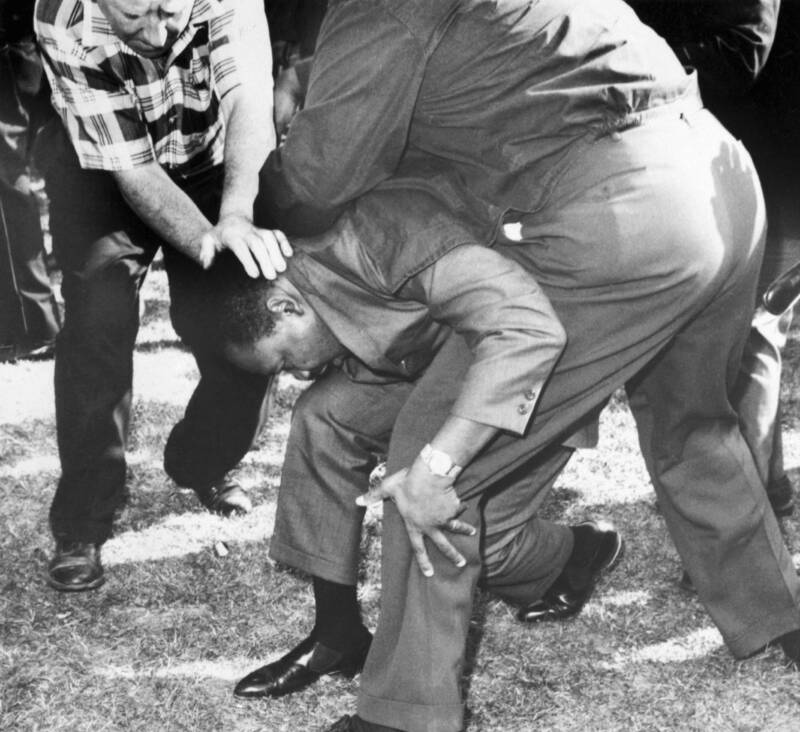

On August 5, 1966, King led a march through Marquette Park. In response, hundreds of white counter-protesters descended, wielding bricks, bottles, and rocks. One of them threw a rock right at King’s head and sent him to his knees as worried aides rushed to shield him.

Bettmann/ContributorDuring a 1966 march in Marquette Park, hecklers hit Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in the head with a rock.

“The blow knocked King to one knee and he thrust out an arm to break the fall,” reported the Chicago Tribune. “He remained in this kneeling position, head bent, for a few seconds until his head cleared.”

After recovering, King declared, “I’ve been in many demonstrations all across the South, but I can say that I have never seen, even in Mississippi and Alabama, mobs as hostile and as hate-filled as I’m seeing in Chicago.”

The attack on King was far from the last racial attack in that neighborhood.

Mark Reinstein/Contributor/Getty ImagesFrom the 1960s to the 1980s, Marquette Park was the site of several racist demonstrations. Here, American neo-Nazis and members of the KKK rally in Chicago in 1988.

In 1970, the successor to the American Nazi Party planted its headquarters in Marquette Park. For the next two decades, it grew its base of support among neighborhood residents and other white people who lived nearby. Together, they fought relentlessly against attempts to integrate the city.

One civil rights group marching against housing discrimination in the area in 1976 was met by a thousand-person mob of local residents, Nazis, and a handful of off-duty police officers who shouted, “Marquette stays white.”

When the mob began attacking the marchers with bricks, the police didn’t protect the marchers — and instead started arresting them.

The 1983 Campaign For Chicago’s First Black Mayor

In 1983, Harold Washington ran to become Chicago’s first Black mayor — and he almost immediately faced a racist backlash.

During the primary, Washington’s opponent Alderman Edward Vrdolyak told precinct captains, “It’s a racial thing, don’t kid yourself. I’m calling on you to save your city, to save your precinct. We’re fighting to keep the city the way it is.”

After Washington won the primary, Vrdolyak endorsed his Republican opponent, who ran on the slogan, “Bernie Epton… before it’s too late.”

Jacques M. Chenet/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty ImagesIn April 1983, Harold Washington won a tight race to become Chicago’s first Black mayor.

On March 27, 1983, Washington campaigned in an all-white neighborhood on the Northwest Side of the city with former Vice President Walter Mondale. Outside St. Pascal Church, they were met with racist slurs and stones. In footage that aired across the nation, a white man screamed “n*gger lover” at Mondale.

And so the Washington campaign turned the racist footage into a campaign ad that said, “When you vote on Tuesday, make sure it’s a vote you can be proud of.”

On April 12, 1983, Harold Washington became the city’s first Black mayor – squeaking by with 51.7 percent of the vote.

Precinct coordinator Jacky Grimshaw summed up the campaign as such: “Though race was always in the background, our message was vote for the most qualified candidate, Harold Washington. We weren’t running a race-based campaign. But they were.”

Racism In Chicago Today

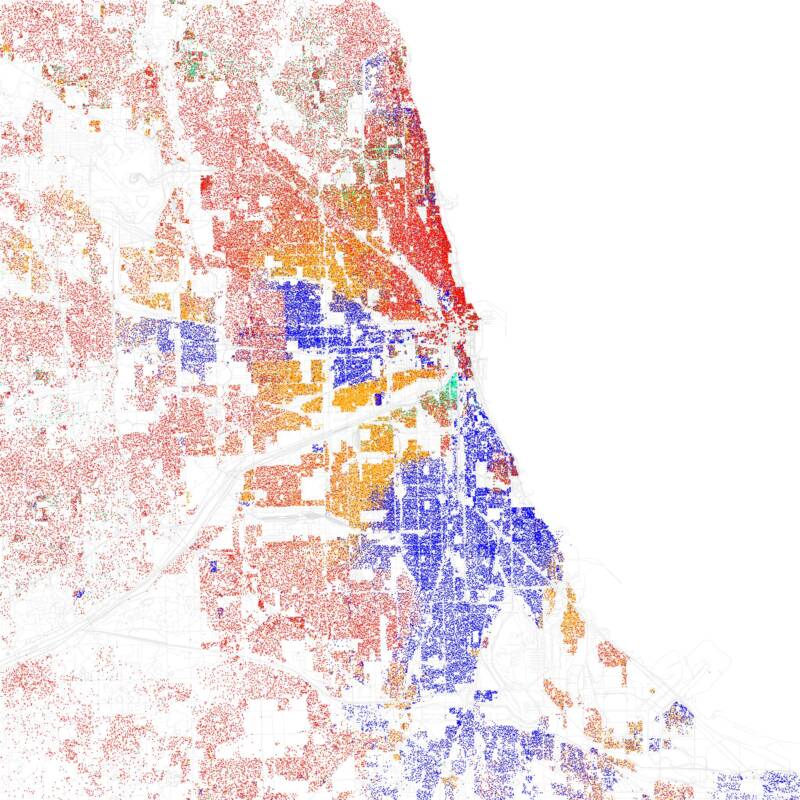

Eric Fischer/FlickrA map showing racial segregation in Chicago based on 2010 census data. Blue areas represent Black residents, red areas represent white residents, and yellow areas represent Latino residents.

Today, Chicago remains one of the most segregated cities in the country. Black Chicagoans live on the South Side and West Side, while white Chicagoans stick largely to the North Side.

Even though many blatant signs of segregation, like the notorious Cabrini-Green Homes, have been torn down, Chicago remains divided. And this is certainly not by accident.

Landlords continue to discriminate against Black Chicagoans today. A 2019 WBEZ analysis found a 24 percent increase in Section 8 voucher holders living in majority Black communities since 2009 and a 25 percent decrease in voucher holders living in majority-white areas.

Multiple landlords rejected resident Lekisha Nowling when she tried to move her family out of West Garfield Park. “It’s a stigma attached to Section 8 that we don’t want to work, we’re nasty, we’re not educated, we don’t take care of ourselves, our children are just reckless,” Nowling told WBEZ. “We’re lying, we’re on welfare, whatever.”

This stigma only reinforces segregation in an already segregated city.

“Throughout the 20th century—and perhaps even in the 21st—there was no more practiced advocate of housing segregation than the city of Chicago,” writes Ta-Nehisi Coates. “Housing discrimination is hard to detect, hard to prove, and hard to prosecute. Even today most people believe that Chicago is the work of organic sorting, as opposed to segregationist social engineering.”

Chicago wasn’t the only city in the North that experienced a backlash against racial equality. Learn more about the ugly history of the anti-civil rights movement and then check out shocking photos of white Americans protesting civil rights.