It was once almost universally accepted that Robert Peary was the first man to make it to the North Pole in 1909, but a re-examination of his records in the 1980s cast serious doubt on his claim.

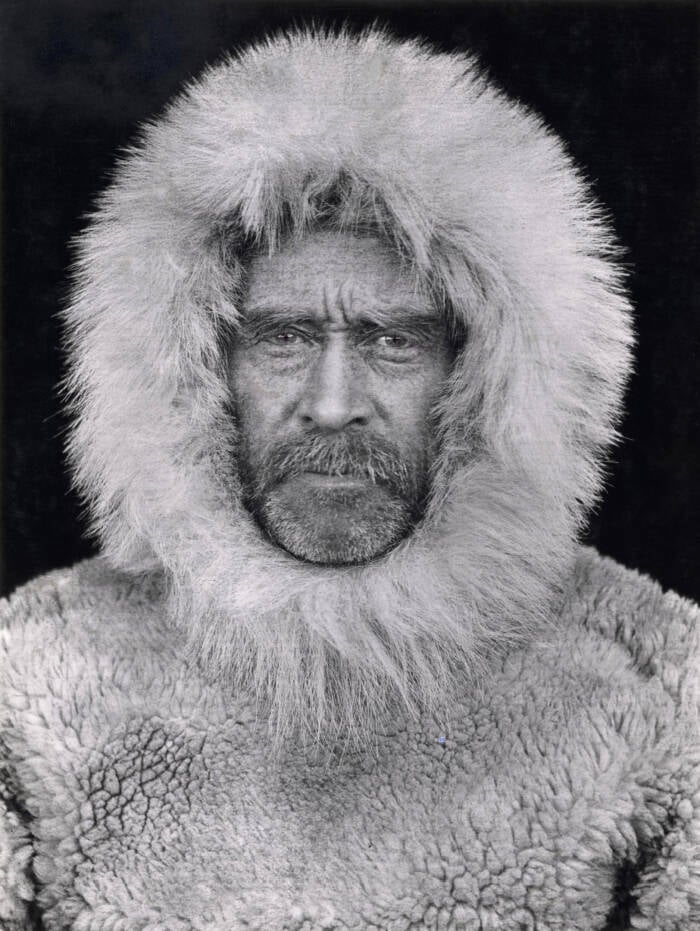

Wikimedia CommonsExplorer Robert Peary vowed to reach the North Pole before anyone else — at any cost.

“Peary Discovers the North Pole After Eight Trials in 23 Years,” declared The New York Times on Sept. 7, 1909. Indeed, it initially seemed like American explorer Robert Peary was the first man to reach the top of the world. But it was soon learned that another paper, The New York Herald, had awarded the historic discovery to a different explorer just one week earlier. Peary refused to give up his claim to the award, and launched a campaign against the other adventurer to secure his title.

From the start, the race to the North Pole drove Peary to extreme lengths.

Peary was desperate to discover something new, and eager to make a name for himself. In fact, in one letter to his mother, he wrote, “I must have fame.”

Did Robert Peary actually reach the North Pole? Did he at least believe that he did? Or did he intentionally mislead the world?

Robert Peary’s Polar Expeditions

Born on May 6, 1856, in Cresson, Pennsylvania, Robert Peary first made a name for himself as a U.S. Navy civil engineer. But by the time he reached his 30s, he had become obsessed with the Arctic, partly due to his naval assignments and reading stories about failed Arctic expeditions.

Of course, he also desired fame and success.

“I don’t want to live and die without accomplishing anything or without being known beyond a narrow circle of friends,” Peary once wrote to his mother.

U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric AdministrationRobert Peary took leave from the Navy for his expeditions.

So Peary eventually took leave from the Navy to sail north. He explored Greenland’s ice, and proved definitively that it was an island. And exploration was a family affair — Peary brought his wife along on some expeditions, and she even ended up giving birth to a child while in Greenland.

But Greenland was not the biggest prize in Peary’s mind. He vowed to be the first man to successfully reach the North Pole.

Yet every expedition seemed to fall short. On one, Peary broke his leg. On another, his feet froze and he ended up losing eight toes.

Library of CongressRobert Peary’s daughter Marie, born in the Arctic, became known as the “Snowbaby.”

In 1906, Peary returned from the Arctic with shocking news. While he had not reached the North Pole, he said he had found a new continent. The explorer named the new land for one of his sponsors, a banker named George Crocker.

Crocker Land floated in the Arctic ice, Peary claimed in a book called Nearest the Pole. But when explorers tried to confirm Peary’s discovery, they only found ice. It took decades before the alleged find was finally disproved.

The Push For The Pole

By 1909, Robert Peary was taking on yet another polar expedition. Surrounded by dozens of men and over 200 sled dogs carrying supplies, Peary eventually reached the 88th parallel. He left behind the larger support party and pushed for the Pole with a party of six men and 40 dogs.

The voyage across sea ice was exhausting.

On April 6, 1909, Peary’s fellow adventurer, the pioneering Black explorer Matthew Henson, asked, “We are now at the Pole, are we not?” Peary answered, “I do not suppose that we can swear that we are exactly at the Pole.”

National Archives and Records AdministrationA photo taken by Robert Peary, showing Matthew Henson and four Inuit men at a location purportedly believed to be the North Pole.

Peary later used his sextant to take measurements, keeping the results to himself. He eventually buried a piece of the American flag in the ice and told his crew that they could go home — they had apparently reached the Pole.

On his journey home, still surrounded by ice, Peary learned that another American explorer — Frederick Cook — was claiming that he had reached the North Pole a year before him. Peary knew Cook well; he had traveled on some of Peary’s previous expeditions and even helped set his broken leg.

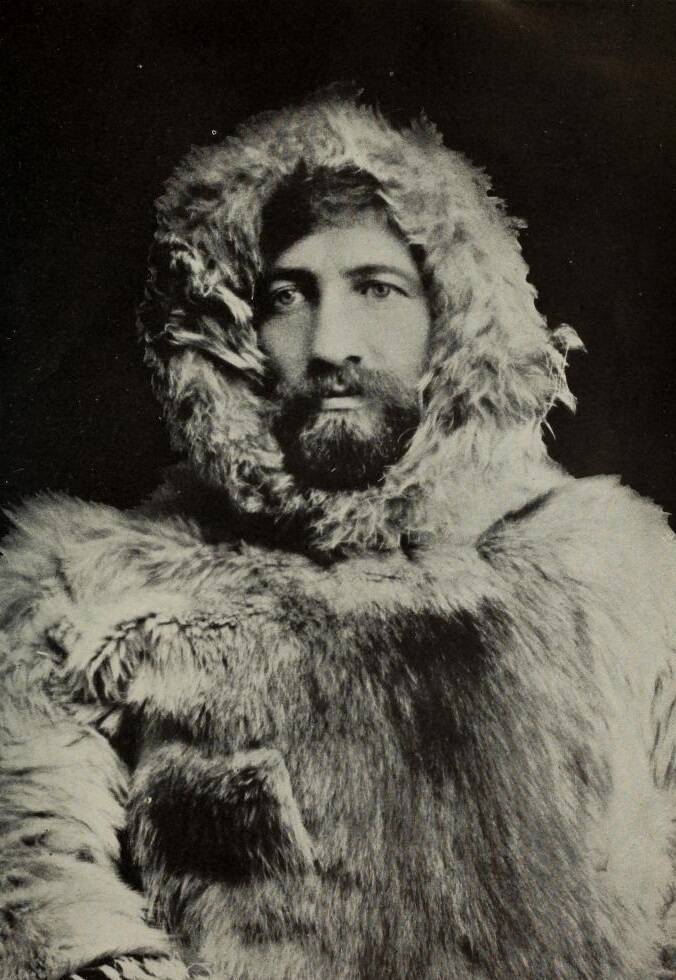

Wikimedia CommonsExplorer Frederick Cook claimed he reached the Pole a year before Robert Peary.

As it turned out, Cook had left his records and instruments in the same Indigenous settlement that Peary’s ship passed. Peary refused to carry any of Cook’s trunks, forcing them to be left behind. They’ve never been recovered.

How Robert Peary’s North Pole Story Was “Verified”

Robert Peary was desperate to secure his claim to the North Pole. After reaching the U.S., Peary and his supporters quickly launched a campaign to discredit Cook. Peary also convinced the National Geographic Society, which had helped fund his expedition, to back his version of events.

As the public debated the rival claims, Peary turned to Congress for support.

Metropolitan Museum of ArtAn image of Robert Peary’s ship.

Peary presented his diary to the Naval Affairs Subcommittee of the U.S. House of Representatives in 1911. “A very clean kept book,” declared one representative. “How was it possible to handle this greasy food and without washing write in a diary daily and at the end of two months have that same diary show no finger marks or rough usage?”

Another representative concluded, “We have your word for it… your word and your proofs. To me, as a member of this committee, I accept your word. But your proofs I know nothing at all about.”

While Congress eventually declared Peary as the winner of the race to the North Pole, the record also noted “deep-rooted doubts” about Peary’s claim.

Arctic Stories Unraveled

What about Crocker Land? Later expeditions found nothing where Robert Peary promised land. And even Peary’s own notes from his travels mentioned nothing about Crocker Land. In his diary, Peary reportedly scrawled, “No land visible,” on the day he supposedly sighted Crocker Land.

The “new continent” seemingly only appeared when Peary decided to publish a book to raise money for his next attempt at reaching the North Pole.

Metropolitan Museum of ArtAn image of icebergs from one of Peary’s expeditions.

“Crocker Land is a fabrication by Peary from the start,” historian David Welky told National Geographic.

It wouldn’t have been Peary’s only deception. Disturbingly, he was also known to have deceived six Inuit people into returning to America with him after one of his expeditions, only to have them be studied at a museum for the sake of “anthropology” — an experience that would kill four of them after they became infected with a strain of influenza to which they had no resistance.

The infamous tale about Crocker Land — and Peary’s treatment of Indigenous people — begs the question about Peary’s most famous claim. Did he really make it to the North Pole as he said he did?

A re-examination of Peary’s records in the 1980s by the National Geographic Society concluded that Peary did not have enough evidence to prove his claim. Due to navigational errors and other issues, his team may have actually fallen just 30 miles short of their goal.

Winners And Losers

In the race for the North Pole, it’s difficult to say whether Robert Peary or Frederick Cook could ever be declared the winner. One reason why it was so hard to confirm who reached the North Pole first was that the Pole sits on a sheet of floating ice, in comparison to the South Pole, which sits securely on the landmass of Antarctica.

While Roald Amundsen could easily plant his flag at the South Pole once he reached it, any flag planted at the “North Pole” was guaranteed to move with the ice. The lack of GPS and other modern navigational tools made the determination even more challenging.

Yet in his lifetime, Peary was celebrated as the explorer who claimed the prize. Why did Peary win according to the world? It’s possibly because he had stronger backers — and a willingness to destroy Cook’s reputation.

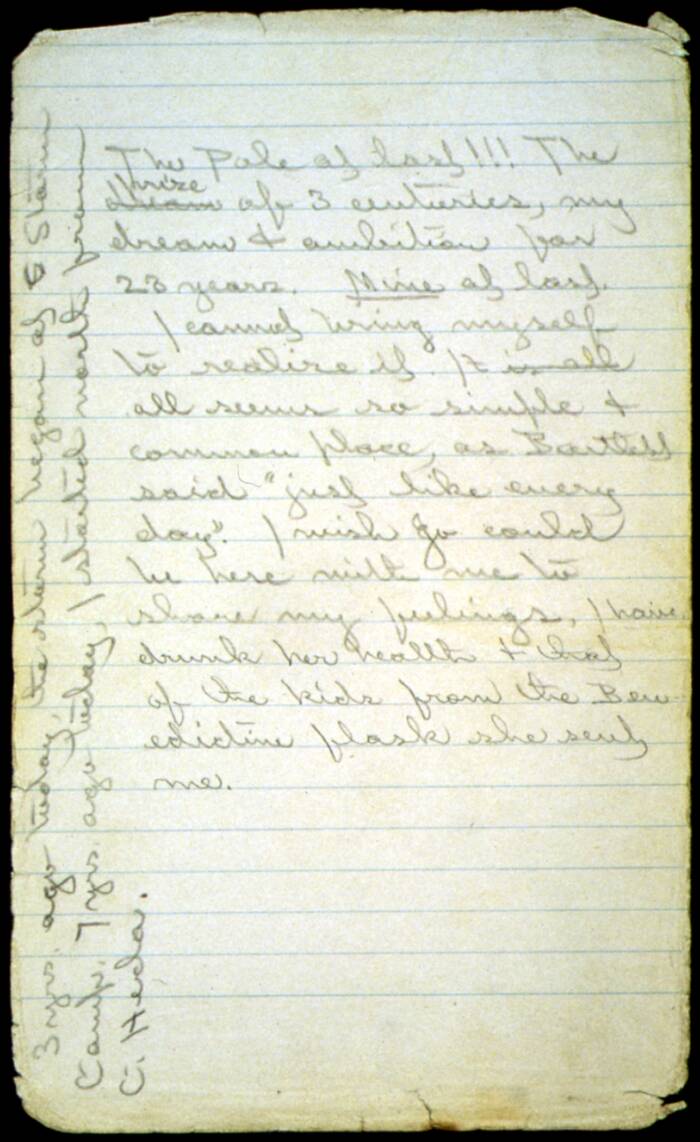

U.S. National Archives and Records Administration“The Pole at last!” Peary recorded in his diary on April 6, 1909.

It’s also worth noting that Cook was eventually convicted of mail fraud in connection with his oil business, which certainly didn’t help matters. The polar controversy may have influenced his sentence, as the judge in his case declared, “You have at last got to the point where you can’t bunco anybody.”

But while Peary’s story was once almost universally accepted, many experts view it with skepticism today. And even if Peary’s expedition was somehow the first to make it to the North Pole, it’s possible that he wouldn’t actually be the first man at the top of the world, as he was accompanied by Henson as well as Inuit guides.

While Robert Peary went to extreme lengths to secure his reputation, one question remains unanswered: Did he truly believe he reached the North Pole — or did he mislead the world to earn fame? Perhaps only Peary knew the truth.

Next, learn about the death of Charles Francis Hall, the Arctic explorer who may have been poisoned by his own crew. Then, go inside the lost Franklin Expedition, the Arctic voyage that ended in cannibalism.