As turmoil roiled in Los Angeles in April 1992, Korean store owners were abandoned by the LAPD and forced to fend for themselves. The results were disastrous.

Getty ImagesWith no assistance from the LAPD, Korean American business owners, now called “roof Koreans,” and other residents of South Central were left to fend for themselves.

In 1992, Americans watched South Central Los Angeles go up in flames on the news. Tensions inside the neighborhood — a mix of racial minority demographics long plagued by urban blight — reached a boiling point after multiple incidents of racial violence against Black residents.

One of them was the shooting of Black teenager Latasha Harlins by a Korean American store owner. The shooter, Soon Ja Du, served no jail time for the murder.

Then, chaos broke loose following the acquittal of white officers who had beaten Rodney King, an African American man, within an inch of his life on camera.

During the violent uprising that followed, Korean Americans took up arms to protect their businesses from looters. This move exacerbated tensions in the community and led to the urban legend of “roof Koreans” shooting looters. However, the truth was more complicated — and much more tragic.

A Decade Of Death

Getty ImagesOnce the uprising was in full-swing, residents’ calls to 911 were largely ignored. Police were not deployed until three hours after the riots had begun.

The infamous uprising that saw neighborhoods in South Los Angeles burn up in flames and Korean Americans take to their roofs with guns lasted five days. The incident was foremost an accumulation of the unrest that had been building in the community for a long time.

South Central L.A. was undergoing massive shifts in its population. Between the 1970s and 1980s, the community was predominantly African-American. But a wave of immigrants from Latin America and Asia in the following decade shifted the neighborhood’s racial makeup. By the 1990s, Black residents were no longer the majority.

As is often the case with minority communities, the local government largely neglected South Central L.A. The decade leading up to the mid-’90s in Los Angeles is widely known as the “decade of death,” a reference to the unprecedented deaths caused by the rise in crime and the growing crack epidemic that swept the nation.

Some 1,000 people were killed each year during the height of the violence, many of whom were connected with gang activity.

Economic anxiety and culture clash soon bred racial resentment, particularly between Black and Korean Americans. The Korean American population was growing rapidly. Because they had limited employment opportunities, many of them started their own businesses in the neighborhoods.

Violent Acts Of Racism Spark Fury

Unrest in South Central L.A. reached a tipping point following two highly-publicized cases involving Black victims of racial violence.

Getty ImagesKorean American business owners took up arms and positioned theirselves on the roofs of their buildings at the height of the riots.

On March 3, 1991, the brutal police beating of a Black man named Rodney King who was chased by police over a traffic violation was captured on camera. Then, two weeks later, a 15-year-old Black teenager named Latasha Harlins was shot to death by a Korean American store clerk. She claimed that the girl was trying to steal a bottle of orange juice. She was not.

Even though they were separate incidents, the racism in these acts of violence weighed on the neighborhood’s Black residents. Already suffering from systemic discrimination that kept them in poverty, it didn’t take long before the initial sparks of discord turned into complete civil unrest.

The 1992 L.A. Uprising

Gary Leonard/Corbis via Getty ImagesThe 1992 LA uprising lasted for five days. Nearly 60 residents of varying backgrounds were killed in the violence.

On April 29, 1992, the verdict in the Rodney King trial finally came. A nearly all-white jury acquitted the four white LAPD officers involved in his beating. The streets of South Central L.A. quickly devolved into chaos following what many saw as an unjust outcome.

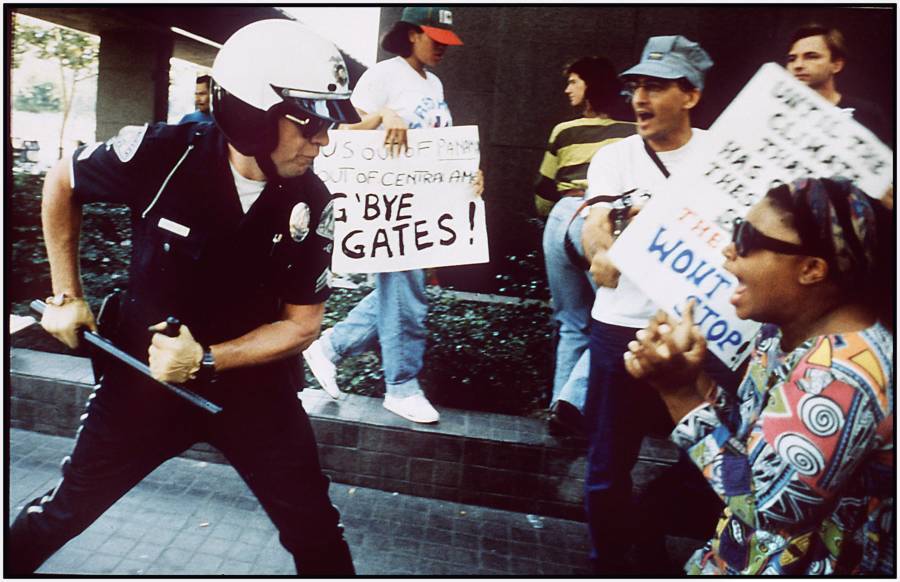

Within hours, angry residents took to the streets to voice their despair. Hundreds gathered in protest outside the LAPD headquarters. Others took their frustrations out by looting and burning down buildings. Looters and arsonists, unfortunately, targeted many local businesses, including Korean-owned shops.

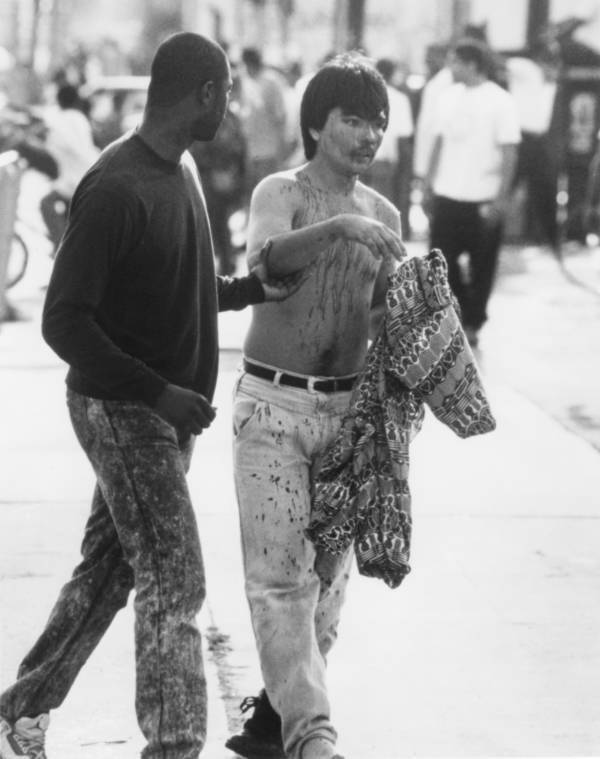

Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty ImagesTwo residents walk out of the chaos taking place on the streets of Los Angeles.

In addition to property damage, plenty of physical violence ensued. Angry mobs targeted a Chinese immigrant named Choi Si Choi and a white trucker named Reginald Denny and beat them during live coverage of the riots. Local residents saved the victims and pulled them out of harm’s way.

The 1992 L.A. Riots lasted for five days.

According to resident accounts, law enforcement did little to quell the unrest. Unequipped to contain the looting crowds, they pulled back and left South Central residents on their own, including business owners in the Koreatown neighborhood.

“On the side of the LAPD, it says ‘to serve and protect,'” said Richard Kim, who armed himself with a semiautomatic rifle to guard his family’s electronics store. His mother suffered a gunshot wound while trying to shield his father, who was safeguarding the store. “[The police] were neither serving us or protecting us.”

Mark Peterson/Corbis via Getty ImagesKorean Americans store owners, many who had never handled firearms before, quickly armed themselves with handguns and rifles.

When it was all over, the chaos killed nearly 60 people and injured thousands of others. Victims of the violence included people of varying backgrounds from Black residents to Arab Americans.

After the unrest finally ended, experts assessed about $1 billion in property damage had been done. Because Korean Americans owned many of the stores in the area, they endured much of the riots’ economic loss. About 40 percent of property damaged belonged to Korean Americans.

“Roof Koreans” Took Up Arms To Protect Their Businesses

Getty ImagesAn estimated 2,000 Korean American-owned businesses and stores were destroyed during the LA riots.

Richard Kim was far from the only Korean American resident forced to take up arms to protect his family’s business. Images of Korean American civilians shooting in the direction of looters permeated the news.

It was the first time many residents, like Chang Lee, had ever held a gun. But amid the chaos and violence, Lee found himself with a borrowed gun, trying to protect his parents’ business. In doing so, he left his own business vulnerable.

“I watched a gas station on fire, and I thought, boy, that place looks familiar,” Lee recalled during one night of the unrest. “Soon, the realization hit me. As I was protecting my parents’ shopping mall, I was watching my own gas station burn down on T.V.”

Business owners armed themselves and their relatives with rifles. Korean Americans on rooftops communicated through walkie talkies as if in the middle of a war zone. The L.A. Riots are known as “Sa-i-gu” among the city’s Korean American community, which translates to “April 29,” the day the destruction began.

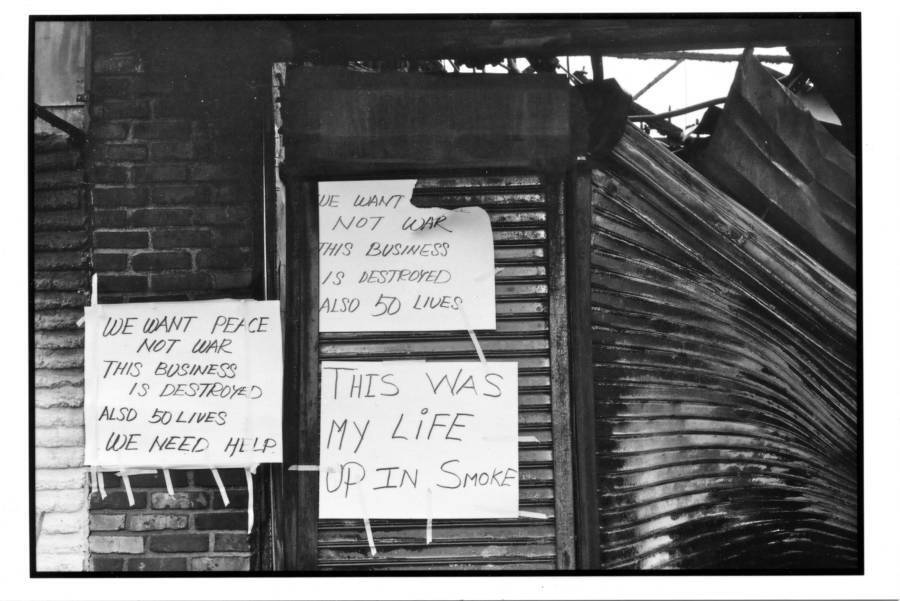

Makeshift signs posted up on destroyed businesses.

Depictions of the armed Korean American store owners on rooftops would come to define the L.A. uprising and still spark mixed reactions today. Some interpreted the “roof Koreans” as “gun-toting vigilantes” rightfully defending their properties.

Others viewed their aggression against the predominantly Black crowds as the embodiment of anti-Black attitudes that exist in Asian communities.

But these images of “roof Koreans,” as recent memes have dubbed them, above all symbolized America’s history of inequality — and especially inequality pitting minority communities against each other.

How The “Rooftop Koreans” Dealt With The Aftermath Of The Unrest In L.A.

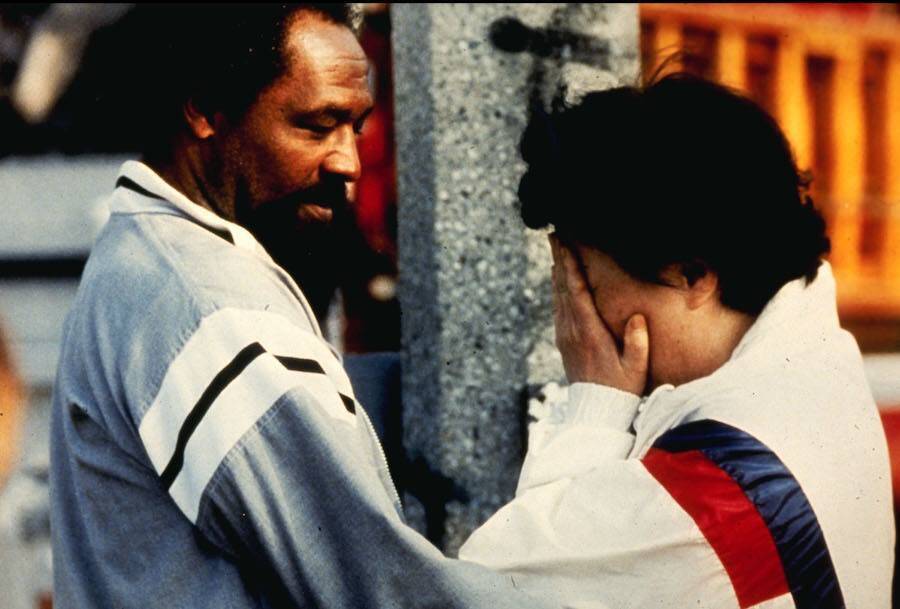

Steve Grayson/WireImageA Korean store owner is comforted by another resident after she discovered her business looted and burned in South Central Los Angeles during the uprising.

The 1992 L.A. uprising remains one of the bloodiest to ever overtake the city. And though there were undoubtedly racial divides — which stretch far back across the history of America — that contributed to the violence, to paint the unrest as merely a clash between cultures would be a gross oversimplification.

As one Asian American man seen in the Smithsonian’s The Lost Tapes: L.A. Riots documentary aptly said: “This is no longer about Rodney King…This is about the system against us, the minorities.”

Indeed, the L.A. uprising was a symptom of the systemic discrimination against minority communities in the U.S., which has left these communities at the margins — and subsequently fighting for limited resources.

“[The model minority myth] came about when Black power movements were starting to gain momentum, so [politicians] were trying to undercut those movements and say, ‘Asians have experienced racism in this country, but because of hard work, they’ve been able to pull themselves up out of racism by their bootstraps and have the American Dream, so why can’t you?'” explained Bianca Mabute-Louie, an ethnic studies adjunct at Laney College, in an interview with Yahoo News.

“In those ways, the model minority myth has been a tool of white supremacy to squash Black power movements and racial justice movements.”

Getty ImagesThe poor response from the government during the South Central unrest showed minority residents that local officials had forsaken them.

Even though technically no looters were killed in the gunfire exchange with Korean Americans store owners, blood was spilled amid the conflict. Patrick Bettan, a 30-year-old Algerian-born Frenchman who worked as a security guard at one of the shopping centers, was accidentally killed by one of the armed business owners.

And an 18-year-old Korean American boy named Edward Song Lee was also shot to death amid the chaos when business owners mistook him for a looter.

These deaths and countless others scarred the community both physically and psychologically when the five days of violence ended.

In the end, the true victims of the 1992 L.A. uprising were the people. The violence that broke out during that week of unrest remains embedded in the memory of the city’s people to this day.

Now that you’ve learned the tragic truth behind those “roof Koreans” memes, take a look at the shocking photographs of the Watts Rebellion of 1965. Then, explore 1970s Harlem in these stunning photographs.