If confirmed, this would be the first example of "virgin birth," or parthenogenesis, ever observed in smoothhound sharks.

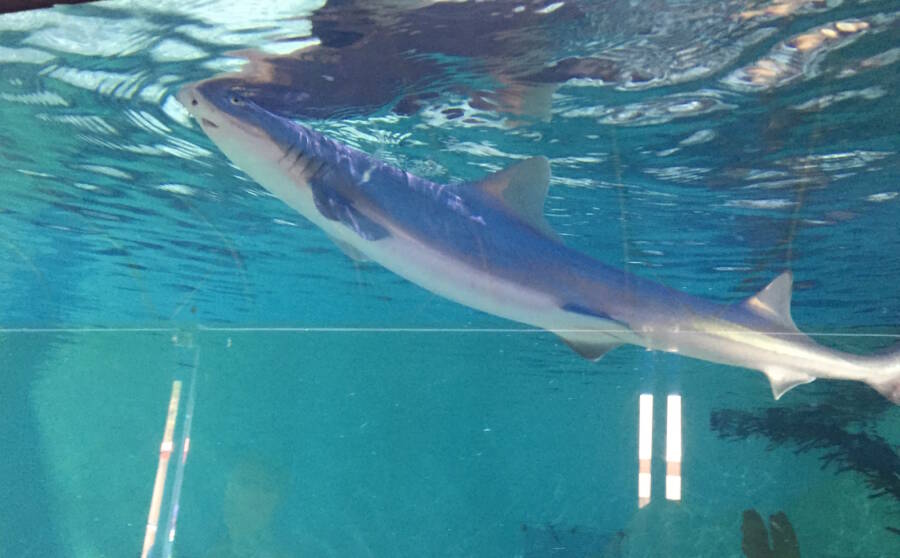

Wikimedia CommonsA female smoothhound shark like this one gave birth without a male partner.

The aquarium staff at Cala Gonone Aquarium in Sardinia, Italy, recently came across a curious sight. In a tank that held two female sharks, they suddenly found a third. The new baby appears to be the result of a rare “virgin birth.”

“Incredible pink ribbon at #AquariumCalaGonone!” the aquarium announced on Facebook.

For 10 years, the aquarium has had two female smoothhound sharks (mustelus mustelus). They shared the tank only with each other and had no interaction with a male. So how did one get pregnant and give birth? Is it truly an example of “virgin birth”?

Sort of. Through a phenomenon called parthenogenesis — a term derived from the Greek for “virgin birth” — a female can self-fertilize her own eggs. That’s what scientists believe happened to the shark at Cala Gonone Aquarium. If so, it would represent the first time a smoothhound shark has given birth via parthenogenesis.

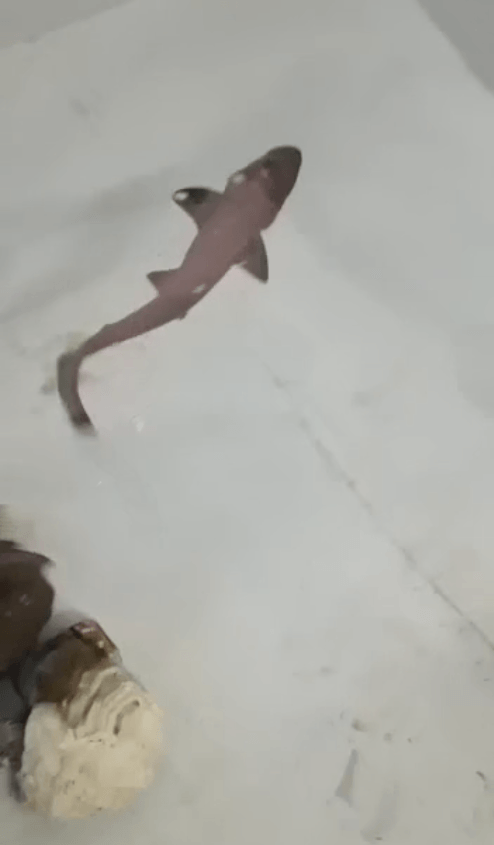

Cala Gonone AquariumSo far, the baby shark is doing well.

“[Parthenogenesis] has been documented in quite a few species of sharks and rays now,” explained Demian Chapman, the director of the sharks and rays conservation program at Mote Marine Laboratory & Aquarium in Florida.

“But it is difficult to detect in the wild, so we really only know about it from captive animals.”

To date, parthenogenesis has been detected in a number of species. Snakes, sharks, lizards, fish, and insects like bees can reproduce through parthenogenesis.

So how does parthenogenesis work? Normally, animals that reproduce sexually combine egg and sperm cells. But in parthenogenesis, the egg cell combines with a “polar cell.” This cell contains a duplicate of an egg’s DNA. Lacking a male partner, females can use the polar cell to fertilize an egg.

As a result, the offspring of parthenogenesis get 100% of their DNA from their mother and are always female.

“The mother is XX, and so she will only pass on X chromosomes to the offspring,” explained Christine Dudgeon, a biosciences researcher at the University of Queensland.

However, the offspring are generally not an exact genetic clone of their mothers. That’s because sex cells contain random combinations of genetic materials. Though the offspring’s DNA may strongly resemble its mother, it has a different combination of genes.

Marine biologists in Italy suspect that’s what happened at Cala Gonone Aquarium. Currently, they’re testing the baby shark’s DNA to see if they’re right.

But that still leaves a question — why would a shark, or any animal, turn to parthenogenesis to reproduce? Especially since offspring born via parthenogenesis are less likely to survive?

In fact, parthenogenesis is something of a biological last resort. Generally, females will seek out a male when it’s time to reproduce. But sometimes they simply can’t find one.

Males in the wild might get wiped out by climate change, overfishing, predation, or disease, which might prompt females to turn to parthenogenesis. And females in aquariums have even fewer options. As a result, explained Chapman, they might become pregnant through parthenogenesis.

And although offspring born via parthenogenesis might have lower chances of survival, many do develop normally and go on to live long lives.

“[When] they do survive, many have normal lives, and some can even reproduce,” said Chapman.

So far, that seems to be the case for the baby shark born in Italy. On Facebook, the Cala Gonone Aquarium in Sardinia announced that they’d named her “Hope.”

“Ispera, the name chosen for the little one, in Sardinian means hope,” the aquarium wrote, “and a birth in the Covid era it certainly is.”

After reading about the “virgin birth” of a shark in Italy, learn about the three-toed skinks, lizards that can lay eggs and give birth. Or, look through this fascinating list of facts about great white sharks.