Up to 350,000 Jews were gassed to death at the Sobibór concentration camp in Poland. But a prisoner uprising forced the Nazis to burn it to the ground.

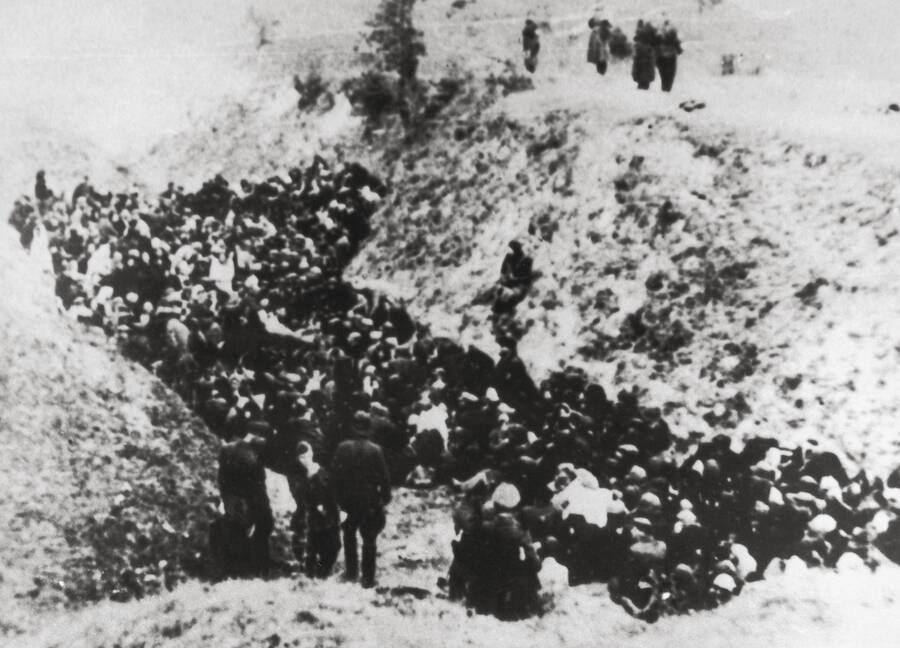

Imagno/Getty ImagesCountless Polish Jews gathered before being executed on the death camp site believed to be Sobibór.

Unlike Dachau and Auschwitz, Sobibór was never a political prison or a concentration camp for forced labor on a mass scale. It existed, from its moment of creation, solely to kill human beings.

Up to 350,000 Jewish people are believed to have been ravaged, killed, and disposed of at the Sobibór death camp. Miraculously, hundreds of them fought back, and 60 Jews managed to escape the death camp. But sadly, their stories from Sobibór remain largely unknown.

Sobibór And The “Final Solution”

Universal History Archive/Getty ImagesJewish families boarding a train to a Nazi extermination camp in Eastern Europe.

The Sobibór death camp was devised by a group of 15, cognac-sipping Nazis in a large riverside villa just outside Berlin.

Adolf Hitler and his second-in-command, Heinrich Himmler, had raised many times the “Jewish question” and turned repeatedly to one official in particular, Reinhard Heydrich to propose “solutions.”

By the end of 1941 the Nazis, already a brutally violent and oppressive regime, would drop all pretenses and shift their focus to the complete extermination of Jewish people in Europe. Heydrich received his order at the end of 1941 and convened the Wannsee Conference on Jan. 20, 1942, so that Germany’s senior government officials could discuss how to successfully carry out the mass killings.

The conference began with a recap of all past efforts that had been aimed “to cleanse German living space of Jews in a legal manner.”

This primarily included forced emigration, whereby wealthier Jews financed their own emigration and, through taxes, funded the travel of poorer Jews. Germany imposed these taxes to ensure that countries receiving exiles would not turn them away for arriving penniless.

By the end of October 1941, 537,000 Jews had been removed from German-controlled areas, including Germany proper and Austria. But too many were still left and displacement on such a mass scale was seen as impossible.

Wikimedia CommonsMemorial wall for victims of the Sobibór camp site. At least 250,000 Jewish victims died at the site.

The new and final “solution” for the Nazis was the “evacuation of the Jews to the east” or in other words their movement deeper into Nazi territory for forced labor, “in the course of which action doubtless a large portion will be eliminated by natural causes.”

Those who did not die in this manner would “have to be treated accordingly,” a phrase that was understood very clearly at Wannsee, particularly because the stronger ones who survived the work would represent “the product of natural selection and would, if released, act as the seed of a new Jewish revival.”

Minutes of the meeting at Wannsee carefully document the number of Jewish people in each European nation.

The greatest number by far were in the USSR (5 million), followed by Ukraine (2.9 million), and the territory of the “General Government” which was the term used for the Nazi government installed to control occupied Poland (2.2 million). Dr. Josef Bühler, secretary of state for the General Government, expressed an eagerness to have the final solution begin in his Polish territory.

Operation Reinhard: Building And Operating Killing Centers

Piotr Bakun/Stiftung Polnisch-Deutsche AussöhnungAn aerial mapping of the Sobibór gas chambers that were recently discovered by researchers.

The plan to relocate and kill more than 2 million Jewish people in Poland eventually took the name Operation Reinhard as a disturbing tribute to the Nazi general who led the Wannsee Conference and was later assassinated by Czech partisans.

The Nazis built three separate death camps in German-occupied Poland — Bełżec, Sobibór, and Treblinka II — and these sites were to carry out one objective only: to kill as many Jewish prisoners as possible.

General Odilo Globocnik led the operation to begin building the Nazis’ death centers, and organized his work into two departments: the first department would oversee the arrangements for the movement of Polish Jews to the killing centers. Meanwhile, the second department would be responsible for the construction and administration of the death camps.

Wikimedia CommonsHermann Erich Bauer, known infamously as the “Gas Master” who operated the Nazi gas chambers at Sobibór.

Police Captain Christian Wirth was put in charge of the operating and constructing the three camps, and Franz Stangl commanded the Sobibór death camp when it opened in April 1942.

Both Wirth and Stangl had been involved in Aktion T4, the atrocious Nazi program that slaughtered more than 300,000 people with disabilities, both mental and physical, in the name of purifying the world of “undesirables.”

As the merciless leaders of what historians refer to as “rehearsal killings” under Aktion T4 — which included the killing of infants and children who were disabled using carbon monoxide exhaust fumes — Wirth and Stangl were entrusted to carry out the Nazis’ “Final Solution” operations at the new killing centers.

After construction of Sobibór was completed in the spring of 1942, Jewish people from the ghettos of Poland were put on trains and deported to the camp. Once the killing centers were operational, the German SS and police started to liquidate the ghettos where many Jews lived, setting them aflame.

Ullstein Bild/Getty ImagesFranz Stangl, who commanded both the Sobibór and Treblinka death camps.

Although the majority of Jewish victims sent to the death camps were from the Lublin area of Poland, each camp site received prisoners from other Nazi territories as well. The victims of Bełżec were Jewish prisoners from the ghettos of southern Poland which included German, Austrian, and Czech Jews. Those deported to Sobibór came from the ghettos of the eastern General Government, as well as from France, the Netherlands, Slovakia, and Germany; most were Jewish but some were Roma.

Meanwhile, deportations to Treblinka II originated from the Warsaw ghetto in central Poland, some districts in the General Government, and the Bulgarian-occupied territories of Thrace and Macedonia.

Mass Killings At The Sobibór Death Camp

U.S. Holocaust Memorial MuseumAerial photo of the Sobibór extermination camp and its immediate surroundings.

Sobibór exemplified the final steps of the Holocaust’s escalation. Construction of the Sobibór death camp began in March 1942 near the railway station of Sobibór near Włodawa, Poland, and continued its mass murder operations until October 1943.

The Sobibór death camp was the second of these killing centers that were sadistically built by forced Jewish labor under the control of SS construction expert Richard Thomalla, who was also tapped to build the two killing centers at Bełżec and Treblinka.

The Sobibór death camp began operating in May 1942 and was divided into three main sections: administration, reception, and killing. Most prisoners were immediately sent straight to the gas chambers right after their arrival at the camp. A narrow path called the “tube” connected the reception area — where camp prisoners were unloaded off the trains and herded toward the “showers” — the killing areas.

Some estimate that at least 170,000 Jewish people and an undetermined number of Poles, Romans, and Soviet prisoners were killed through myriad methods of torture.

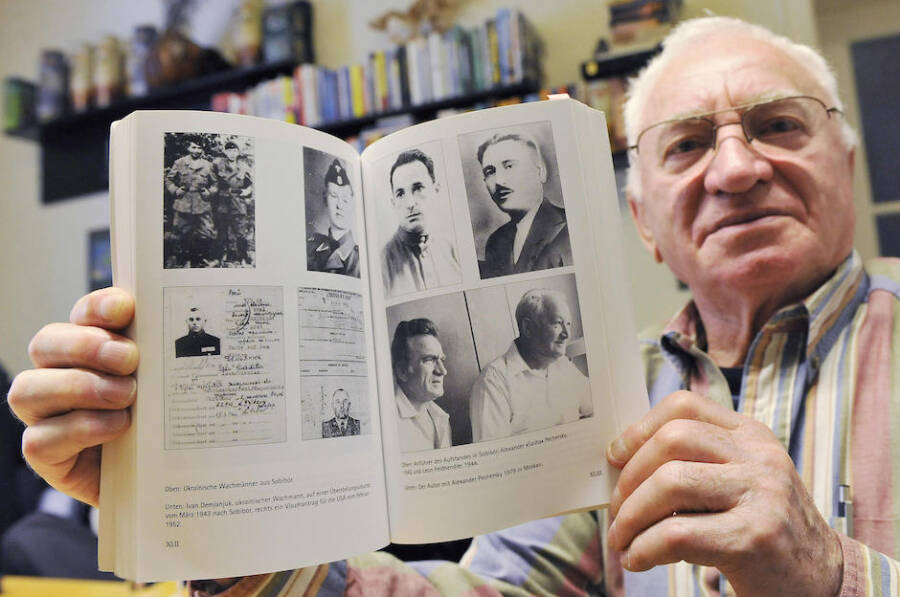

Oliver Lang/AFP/Getty ImagesThomas Blatt, a survivor of the Sobibór extermination camp in Poland with his book about the Nazi camp.

However, that number may be a gross underestimate. According to testimonies given by the Nazi murderers themselves during a Sobibór tribunal held at the Hague roughly two decades after World War II, Professor Wolfgang Scheffler estimated at least 250,000 Jewish captives were murdered, while “Gas Master” Erich Bauer said the number of victims was at least 350,000.

By some estimates, that would make Sobibór the fourth-deadliest extermination camp after Auschwitz, Treblinka, and Bełżec.

Another reason why Sobibór is not as well-known as other Nazi camps is due to the lack of documentation of the site — which was by the Nazis’ design. But what accounts we do have of both the survivors and the Nazi officials that carried out these atrocities paint a horrifying image of the Sobibór extermination camp.

An account from Sobibór survivor Philip Bialowitz in his memoir A Promise at Sobibór confirms the mass killings that would often take place upon the victims’ arrivals.

“I helped Jews out of the trains with all their baggage,” Bialowitz wrote. “My heart was bleeding knowing that in half an hour they would be reduced to ashes…I couldn’t tell them. I wasn’t allowed to speak. Even if I told them, they would not believe they were going to die.”

After the Jewish prisoners were gassed, their bodies were savagely dumped together into huge pits and burned on open-air “ovens” that were constructed from parts of the train tracks. The lucky few that escaped the gas chambers were forced to labor throughout the camp; many of them still ended up dead.

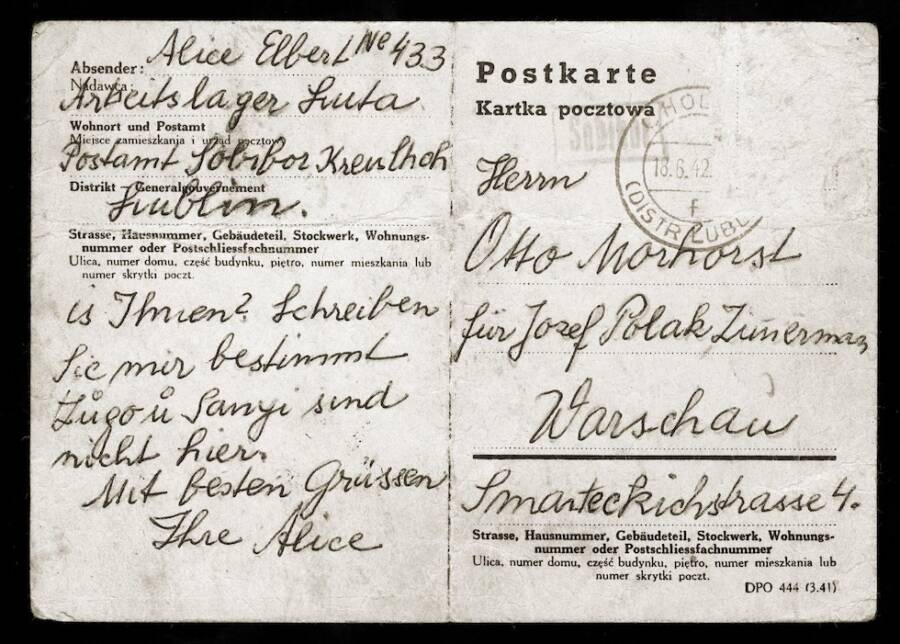

U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum courtesy of Denise Elbert KopeckyA postcard from Sobibór written by Alice Elbert, a Jewish Slovak imprisoned in the Luta forced labor camp near Lublin, to family or friends in Warsaw.

More evidence of the brutality at Sobibór was uncovered when pencil drawings from 1943 were found on a farm in Chelm not far from the camp. The drawings are signed with the name Joseph Richter, though historians know very little about his life. Judging by his drawings and their written locations, it appears he moved freely from place to place.

Richter’s sketches were mostly made on scraps of paper, whatever he could find, and depict harrowing scenes that he witnessed around the Sobibór compound complete with short descriptions written in Polish.

One drawing showed the dead body of a woman by the train racks with the caption, “A wood near camp Sobibór. [Woman] escapes from a transport. On the last wagon a machine gun. The forest is not dense.”

On another sketch that was done on a piece of newspaper, ghostly figures — likely malnourished and beaten Jewish prisoners — peek out from behind a fenced-off train window. Richter wrote: “A transport on Uhrusk station. A hole in the window, blocked with barbed wire. They know…”

Until this day, the identity of the artist behind these death camp illustrations is shrouded in mystery.

The Sobibór Uprising

U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum courtesy of Misha LevSome of the Sobibór prisoners involved in the uprising at the camp site.

On October 14, 1943, a group of prisoners plotted an elaborate and dangerous escape from Sobibór.

At this time Sobibór had been operating for a year and a half. Rumors spread that the camp would soon be liquidated by the Nazis in an attempt to cover up their war crimes. Fearing the camp’s destruction — and its prisoners along with it — the group hatched a daring escape plan.

The underground prisoners group was led by Leon Feldhendler, the son of a rabbi and a Jewish political leader in his native city of Zolkiew, in western Ukraine. But after the arrival of Soviet Jewish POWs at the camp in mid-September, he handed leadership off to Alexander Pechersky, a former Soviet-Jewish soldier who had just arrived at the camp, sparing the gas chamber by convincing the prison guards he knew carpentry.

Leaders of the Sobibór uprising managed to kill off at least 11 SS officers. After a riot broke out, some 600 imprisoned Jews stormed Sobibór’s fortifications made up of minefields and barbed, electrified fences in an attempt to escape to the forest outside. Many did not make it out of the bloody uprising.

Getty ImagesEster Raab (right), a former inmate of the Nazi’s Sobibór concentration camp in Poland, points at Erich Bauer (left) and identifies him as the “Gas Master” at the Sobibór extermination camp.

“Corpses were everywhere,” wrote Sobibór survivor Thomas “Toivi” Blatt in his memoir, The Forgotten Revolt.

“The noise of rifles, exploding mines, grenades and the chatter of machine guns assaulted the ears,” Blatt continued. “The Nazis shot from a distance while in our hands were only primitive knives and hatchets.”

Three hundred prisoners escaped Sobibór that day, though many of them were recaptured and killed in the immediate aftermath. Only about 47 of them survived to the end of the war.

After the revolt, what the escaped prisoners feared came to reality — just a few days later, the Nazis destroyed the Sobibór camp and killed the remaining prisoners. The Germans had planned to transform the killing facility into a holding place for women and children deported west from occupied Belarus after the men of their families were murdered. There were also suspected plans to create an ammunition supply depot at the site.

However, it appears none of these plans came to fruition after Sobibór was liquidated. The site was eventually planted over, disguising the mass killings and tortures that once took place at the death camp.

Remembering The Victims

Claus HeckingArcheologist Yoram Haimi examines bone fragments in the grass at the site of the Sobibór gas chambers.

The mass killings and immense suffering that led to the historic uprising at Sobibór was adapted for the screen in the British made-for-TV film Escape From Sobibór in 1987. The film starred Dutch actor Rutger Hauer as Pechersky and Alan Arkin as Feldhendler. Hauer won a Golden Globe award for his portrayal of the uprising leader.

The story of Sobibór was then adapted to the big screen in 2018’s Sobibór which was сo-written, directed by, and starred Russian actor Konstantin Khabensky. Most of the film was shot in Lithuania and partly funded by the Russian government.

In an interview with Variety, the actor-director said the film “speaks best to audiences who are open to emotionally accept things that are not easy to accept. We have been through 10 countries [with the film] so far, and everywhere this film goes to the heart of these people.”

He also added that the historical weight of the film is, unfortunately, still relevant today. “Humanity hasn’t learned its lessons yet,” he said.

Archaeologists are working to uncover more of the death camp grounds that have been overgrown by dirt and vegetation. Excavations near the Sobibór memorial wall are underway, and researchers have come across small trinkets leftover from the camp’s victims. In 2013, they finally discovered the precise location of the site’s gas chambers.

U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum courtesy of Adam KaczkowskiMemorial at the Sobibór death camp.

Archaeologist Yoram Haimi initiated the excavation project after his first visit to the Sobibór memorial in April 2007. He had come to pay respects to his uncle, who was one of the hundreds of thousands of prisoners murdered at the Sobibór camp.

Back then, only a few commemorative stones and a memorial wall were visible on site — all the horrific deeds committed at the site had been washed away by nature and time. To him, Haimi said, the memorial struck him as “abstract.”

“The museum was closed at the time,” Haimi told Spiegel Online. “You could see memorials, but nothing that showed how and where the murders took place.”

Almost all of the known survivors of the Sobibór death camp have passed away, the last of whom was Ukrainian Semion Rosenfeld, who passed away at a retirement home in Tel Aviv in 2019. He was 96 years old.

Let’s hope that the story of Sobibór is never forgotten again.

Now that you’ve learned about Nazis’ Sobibór death camp, read about the “utterly ruthless” Heinrich Müller, the highest-ranking Nazi never killed or caught. Next, read about Daniel Burros, the Nazi who killed himself after his Jewish background was made public.