Super-Earth is so far away that locating it is much more difficult than just looking through a telescope.

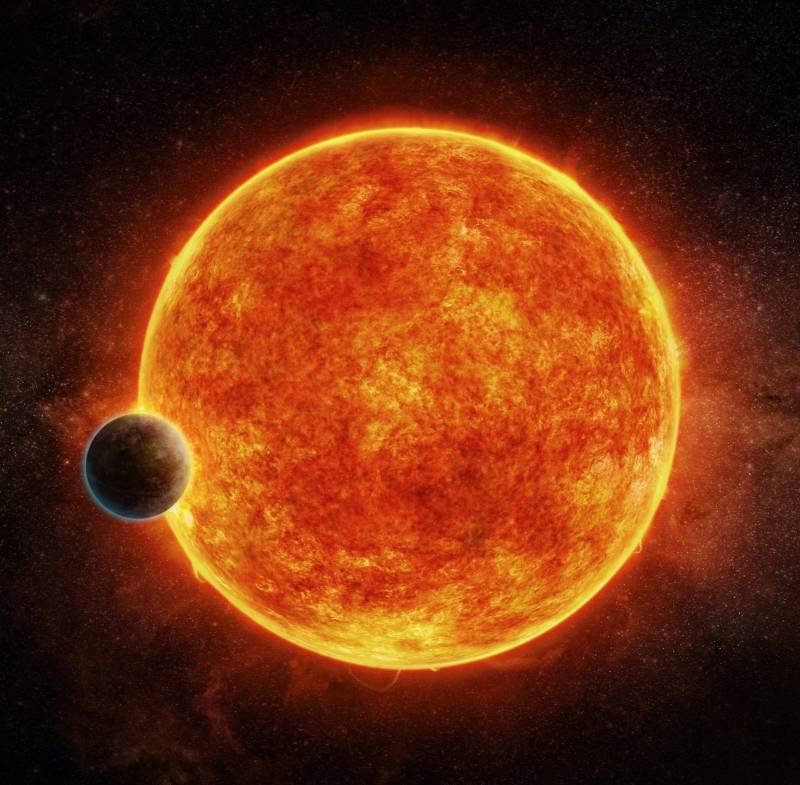

M. Weiss/CfAArtist’s depiction of the newly discovered planet is located in the liquid water habitable zone surrounding its host star, a small, faint red star named LHS 1140. The planet weighs about 6.6 times the mass of Earth and is shown passing in front of LHS 1140. Depicted in blue is the atmosphere the planet may have retained.

Forty light years away in the southern constellation of Cetus, there’s a dim red dwarf star called LHS 1140.

Despite its boring name, this previously unremarkable ball of gas serves as a potentially life-giving sun for the planet LHS 1140 b, which scientists are calling “super-Earth.”

The newfound planet is significantly bigger, heavier and older than our own home, but a new study published in Nature suggests this far-away Earth cousin is our new best bet for finding aliens in outer space.

“This is the first time we’ve found a rocky planet that gives us the opportunity to look for oxygen,” David Charbonneau, one of the paper’s authors, told Scientific American. “This really is the one we’ve been hunting for.”

It’s not the first time astronomers have thought they’d come across the next Earth.

Many planets that look similar to our own from a distance have later proven to be more like Neptune — covered in thick layers of gas that smother any possibility for living organisms.

But super-Earth is special. It’s twice as large as our world and six times as heavy — measurements that suggest a composition of rock and metal, surrounded by a relatively thin atmosphere.

It has a 25-day orbit around LHS 1140, which — because of its dimness — provides only half as much light as our sun, despite the fact that super-Earth comes ten times closer than we ever do.

It’s just enough solar power, scientists say, to make liquid oceans possible.

If there are aliens hanging out by these super-oceans in super-cities on super-Earth, they’re likely confined to one side of the planet. It’s suspected that the world doesn’t turn like ours, leaving one side in constant, cold darkness.

None of these traits make the planet particularly exciting. What’s so great about super-Earth, according to the research, is how astronomers are able to observe it.

Every orbit, the giant rocky planet passes in front of its star so that — when looking from Earth — its atmosphere is perfectly illuminated from behind.

This fortuitous alignment will allow researchers to learn about the atmospheric makeup by studying the starlight — searching for signs of oxygen and other gasses.

Super-Earth is so far away that locating it is much more difficult than just looking through a telescope.

From this distance, the most advanced planet-finding technology can only detect planets by picking up slight gravitational wobbles in the stars they revolve around. Once they painstakingly detect such a minute disturbance, they train the world’s most powerful telescopes on the star and wait for the planet’s silhouette to orbit by.

When it does, it’s an observation akin to “observing the dimming of light caused by a grain of sand moving in front of a candle placed 400 kilometers away,” the researcher who first saw the LHS 1140 planet’s orbit, Thiam-Guan Tan, said.

Once you know the coordinations for a planet’s orbit, then you can start to collect data on its size and mass. Once you have that, you begin the atmospheric observations.

The team looking at super-Earth is excitedly planning future studies — next monitoring the possible alien home’s transit from a telescope in Chile on October 26.

Next, check out these incredible photos of Jupiter being sent back by NASA’s $1 billion probe.