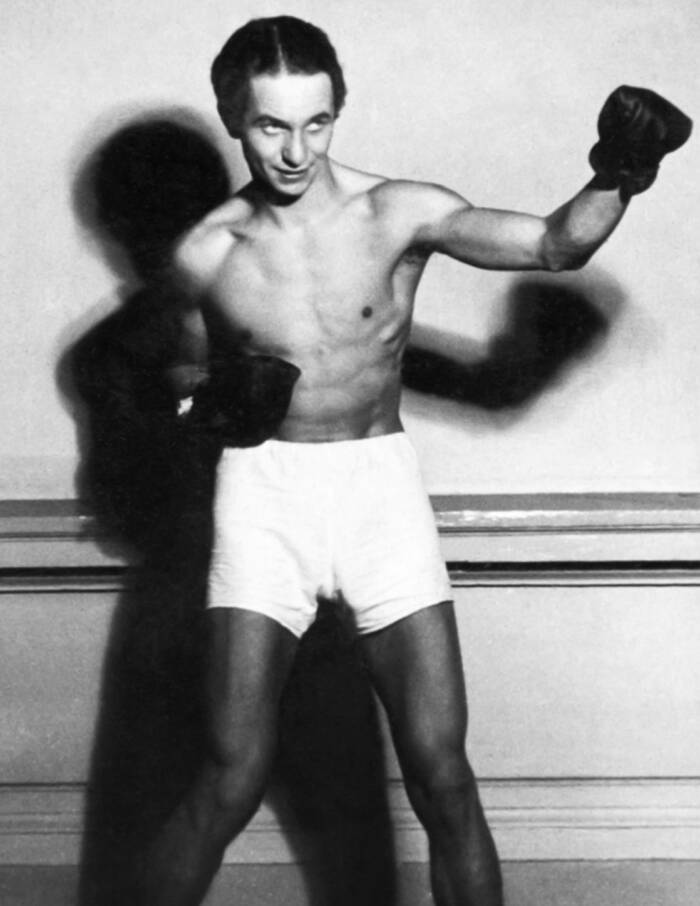

During his time at Auschwitz, Tadeusz Pietrzykowski boxed for the guards' entertainment, earning extra food and privileges which he shared with his fellow prisoners.

Wikimedia CommonsTadeusz “Teddy” Pietrzykowski, the Polish man who boxed for his life at Auschwitz.

One of the first prisoners taken to the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp by the Nazis was a 23-year-old Polish man by the name of Tadeusz “Teddy” Pietrzykowski. Dubbed “Prisoner 77,” Pietrzykowski faced terrible odds at Auschwitz, where more than a million people would perish between 1940 and 1945. But Pietrzykowski managed to survive, largely by winning dozens of boxing matches.

The bantamweight vice-champion of Poland and a champion of Warsaw, Pietrzykowski soon realized that boxing could win him extra food and privileges — provided that he won his bouts. During his time at Auschwitz, Pietrzykowski engaged in between 40 and 60 matches, purportedly only losing just one of them. And while he boxed for the entertainment of the guards, he also became a symbol of hope for his fellow prisoners.

This is the incredible true story of Tadeusz Pietrzykowski, as seen in the 2020 Polish film The Champion of Auschwitz.

A Rising Star In Polish Boxing

Tadeusz Pietrzykowski was born on April 8, 1917, in Warsaw, Poland. He was too young to remember World War I, which ended some months before his second birthday, and spent most his youth focused on sports. Pietrzykowski was interested in soccer as a teenager, and soon showed his skill as a boxer.

He trained with a coach named Feliks “Papa” Stamm, who oversaw the development of scores of young boxers. Pietrzykowski took his training seriously, though Polish News reports Pietrzykowski’s family thought his talents lay more in art than in boxing or soccer.

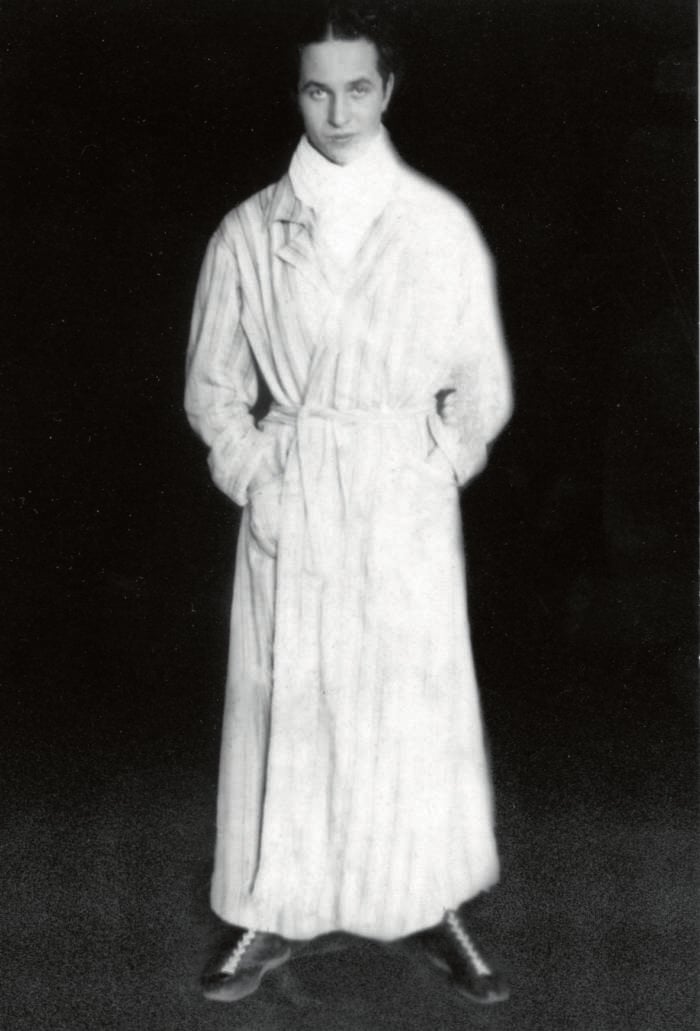

Family Photo Archive of Eleonora SzafranPietrzykowski around 1938.

“Teddy left behind notes about his workouts, which tell us how he was developing tactics and technique,” Dr. Karol Nawrocki, director at the Museum of the Second World War in Gdańs, Poland, told Vice in 2020.

Tadeusz Pietrzykowski showed early promise, competing in matches that placed him among the best in his weight class. While he lacked the size of a heavyweight, his technical skill, sharp footwork, and grit made him a formidable fighter. By 1939, he was considered one of Poland’s young athletes to watch — until fate intervened.

Tadeusz Pietrzykowski’s Deportation To Auschwitz

World War II began on September 1, 1939, when Germany invaded Poland. Pietrzykowski promptly put down his boxing gloves down and joined the fight. He joined a light artillery regiment and defended Warsaw against the Nazis and, when the city fell, headed to France, where thousands of his countrymen were forming a new Polish army under General Władysław Sikorski.

Public DomainGerman tanks in the streets of Warsaw in September 1939.

But Pietrzykowski never made it.

Instead, the Gestapo arrested the 23-year-old on the Hungaro-Yugoslav border. Not long after that, Pietrzykowski became one of the first transports to the newly established Auschwitz concentration camp, where he was branded with the number 77. A Catholic political prisoner, Pietrzykowski was thrust into a new, brutal world that would seek to dehumanize him as much as possible.

Tadeusz Pietrzykowski didn’t start boxing in Auschwitz right away. At first, he was assigned to work in a carpenter’s shop, and though the labor was backbreaking, his prior fitness helped him persevere.

All that changed in March 1941.

Tadeusz Pietrzykowski’s First Fight In Auschwitz

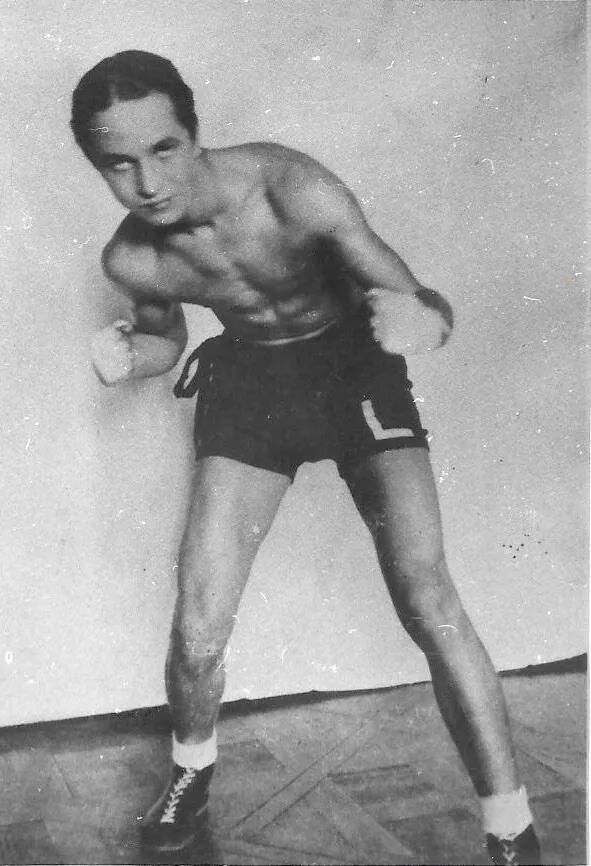

Family Photo Archive of Eleonora SzafranPietrzykowski found that winning boxing matches could earn him extra food, which he shared with his fellow prisoners.

Tadeusz Pietrzykowski’s first fight came about by chance. In 1941, on a Sunday, Pietrzykowski noticed a large crowd near the camp kitchens. Suddenly, one person from the crowd broke away and called to him.

“One of them ran towards me and shouted, ‘Teddy, you want a piece of bread, come quickly. There is a German boxer among us. I’m looking for someone to box with him and beat him. The winner will be rewarded with bread,'” Pietrzykowski recalled of the fight years later. “I weighed 42 kg [92 pounds], but decided to fight right away. I saw a perfectly built blonde, holding gloves that we used in winter during our work. When I was seen, the crowd laughed because I was very skinny.”

Pietrzykowski’s opponent was Walter Düning, a German kapo (a prisoner who oversaw other prisoners), who had been a successful boxer before the war. He was a formidable opponent. But despite the odds, Pietrzykowski outmaneuvered Düning and claimed victory.

That was the moment Pietrzykowski realized that boxing could secure him special privileges at Auschwitz.

“At one point, Walter Düning lowered his gloves,” Pietrzykowski recalled. “He stopped fighting and, appreciating my advantage over him, asked which commando I would like to work in. I replied ‘Tierpfleger’ [animal caretaker] knowing that there could be additional food such as bagasse, swede, and carrots.”

Family Photo Archive of Eleonora SzafranPietrzykowski fought more than 40 matches during his time in the concentration camp.

Slowly but surely, Pietrzykowski became known as a boxer. The Auschwitz guards found him amusing and began “enrolling” him in other fights, sometimes against guards, sometimes against other inmates. The guards often placed bets on the outcomes of the fights, but to call the events sport would be a disservice to the word.

These were exercises in cruelty.

“Teddy had to fight other inmates – many of whom were his fellow countrymen – for food scraps. It was his chance for survival,” Nawrocki explained to Vice.

Victory often meant extra food rations or slightly less brutal treatment, and these scraps of advantage helped Pietrzykowski endure conditions that killed countless others.

But as Tadeusz Pietrzykowski won match after match — he boxed in 40 to 60 contests at Auschwitz, losing just once — he also became a symbol of hope to his fellow inmates.

How Tadeusz Pietrzykowski Became A Symbol Of Resistance

After his initial bout with Düning, Tadeusz Pietrzykowski went on to fight dozens of matches inside Auschwitz. His opponents were often professional or semi-professional boxers from across occupied Europe, many larger and better nourished.

Yet Pietrzykowski won almost all of his fights.

Among prisoners, word of “Teddy’s” victories spread quickly. His triumphs offered them fleeting moments of pride and hope. In a place meant to strip away his dignity, his fists symbolized that resistance, however small, was possible. Pietrzykowski proved that even in Auschwitz, Nazis could be beaten.

United States Holocaust Memorial MuseumThe main entrance of Auschwitz. During his time, there Tadeusz Pietrzykowski became a symbol of hope and resistance.

Indeed, Pietrzykowski was also involved in a different kind of defiance against the Nazis. He’d also began working with the Auschwitz resistance movement, collaborating with Witold Pilecki, who had infiltrated the camp voluntarily under a false name to gather evidence of the Nazis’ crimes.

During his time in Auschwitz, Pietrzykowski participated an assassination attempt of camp commandant Rudolf Höss by loosening the saddle on Höss’ horse. (Höss survived, though he broke his leg). Pietrzykowski also killed Höss’ dog, which had been trained to attack prisoners.

Meanwhile, he and the other prisoners waited for the war to end — and for their freedom.

A Boxer’s Return To Normal Life

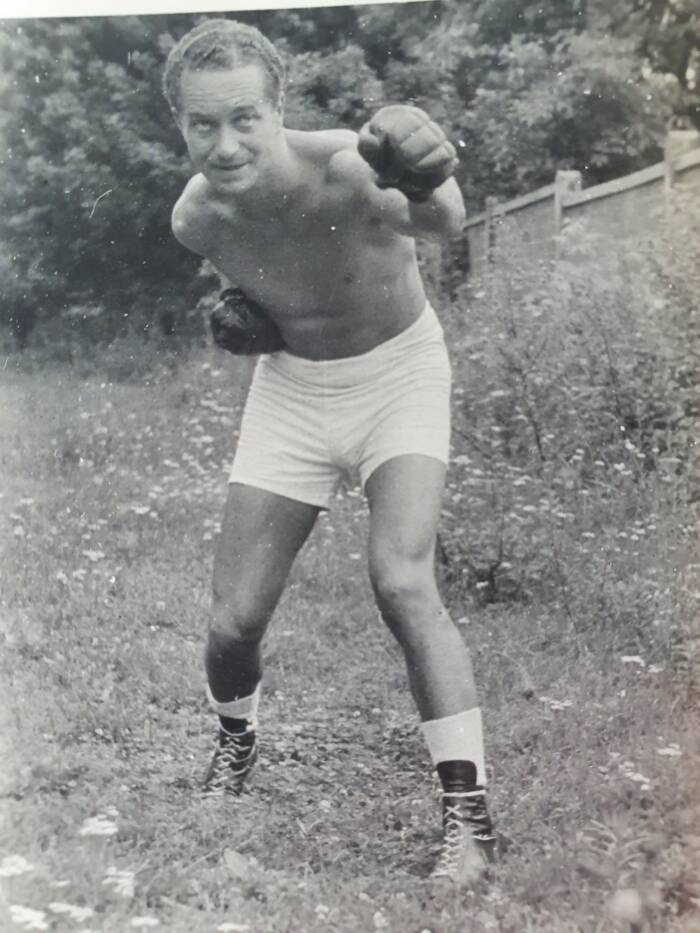

Family Photo Archive of Eleonora SzafranPietrzykowski after the war.

In 1943, Tadeusz Pietrzykowski was transferred from Auschwitz to Neuengamme, a concentration camp near Hamburg. Conditions there were equally brutal. Forced labor and starvation claimed thousands of lives, and Pietrzykowski once again had to box for his life. He continued to fight in matches organized by the guards — around 20 in total — using his skill as a lifeline.

Not long after, he was sent to Bergen-Belsen, one of the most notorious camps in the Nazi system. By the time of its liberation in April 1945, Bergen-Belsen had become a death trap of starvation and disease, littered with mass graves. But somehow Pietrzykowski survived. His body was ravaged by years of imprisonment, but his will remained unbroken.

After the liberation, Pietrzykowski returned home to Poland. His boxing career, interrupted by the war and his weakened health, sadly never fully recovered. But he did not abandon the sport completely. Instead, he became a boxing trainer and physical education teacher in Bielsko-Biała, helping to shape the lives and careers of other promising fighters.

His experience had also given him special insight into endurance and discipline, which he passed on to his students. Before he died in 1991 at the age of 74, he often repeated a simple message to his students.

“To be,” he would tell them, “is to be the best.”

After reading about how Tadeusz Pietrzykowski became the “Champion of Auschwitz,” read about another boxer who fought for his life during the Holocaust: Harry Haft. Then, learn about Kazimierz Piechowski and the Great Auschwitz Escape.