Tezcatlipoca, the Aztec creator god who was often depicted as a jaguar, was credited with helping to form the world — but he also inspired gruesome human sacrifices.

Public DomainTezcatlipoca was the Aztec god of the night sky and the patron deity of warriors.

Like most gods in the Aztec pantheon, Tezcatlipoca is difficult to define in a succinct manner. He was a multifaceted figure, embodying a variety of concepts ranging from the night sky to conflict and sorcery. His animal counterpart, or nagual, was the jaguar, considered by the Aztecs to be a powerful and mystical creature with connections to the Underworld.

The Aztecs revered jaguars, and elite warriors even adorned themselves in jaguar pelts as a way of imbuing themselves with the animals’ strength and ferocity in battle. It makes sense then that Tezcatlipoca was held in high regard by the Aztec people. He was a creator god, the bringer of good and evil, and the patron deity of warriors.

He was considered to be one of the most important gods in the Aztec pantheon, and he was held in equal esteem as his brothers Quetzalcoatl, Huitzilopochtli, and Xipe Totec. Tezcatlipoca features in many Aztec myths, and his worship was widespread across Mesoamerica.

Of course, much of this worship involved human sacrifice.

Tezcatlipoca’s Role In The Aztec Creation Myth

Peter Hermes Furian / Alamy Stock PhotoQuetzalcoatl, the feathered serpent deity, and Tezcatlipoca, the jaguar god.

According to legend, Tezcatlipoca was instrumental in the creation of the world. He was one of four children born to the duo of primordial gods known as Ometecuhtli and Omecihuatl. Along with Quetzalcoatl, Xipe Totec, and Huitzilopochtli, he ushered in the cycle of the Five Suns that brought about the formation, destruction, and reconstruction of the mortal world.

Tezcatlipoca was often portrayed as Quetzalcoatl’s rival. At first, the two brothers worked together to create the world. A massive, crocodile-like creature known as Cipactli sat astride the ocean, demanding flesh to feast upon. Surely, the gods felt, humanity could not survive in a world where such an animal existed.

Quetzalcoatl and Tezcatlipoca transformed into giant snakes, attacking and dismembering Cipactli’s body, from which the Earth and sky emerged. Her hair and skin became trees, plants, and flowers, while her teeth formed the mountains and her eyes became caves.

Tezcatlipoca ruled over this new world during the period of the First Sun, known as Nahui Ocēlōtl, or the Jaguar Sun. During this period, the world was inhabited by a race of giants who eventually displeased the gods. Soon, a conflict arose between Tezcatlipoca and Quetzalcoatl, and Quetzalcoatl ultimately struck Tezcatlipoca down from the sky.

Tezcatlipoca retaliated by sending jaguars to devour the giants, bringing the era to a sudden, violent end.

Ancient Art and Architecture / Alamy Stock PhotoA mask depicting the human skull of Tezcatlipoca.

During the Second Sun, Quetzalcoatl replaced his fallen brother as the new Sun. However, Tezcatlipoca would not abide by this insurrection. He turned all humans on Earth into monkeys, which were then swept away by Quetzalcoatl in a great hurricane, bringing a close to the second age.

The Third Sun saw the ascension of the god Tlaloc. However, his rule was also disrupted by Tezcatlipoca. Once again, seeking to sow chaos, the god seduced Tlaloc’s wife, leaving Tlaloc in a state of deep grief. During his mourning, he neglected his duties, withholding rain from the world and bringing about a great drought.

Tlaloc finally summoned rain, but it was made of fire and destroyed the world and its inhabitants.

Tlalocs new wife, Chalchiuhtlicue, became the Fourth Sun. Though the goddess of water was seen as a kind ruler, Tezcatlipoca once again intervened, accusing her of simply feigning her kindness to deceive humanity. Hurt by Tezcatlipoca’s remarks, Chalchiuhtlicue wept for 52 years, flooding the world and turning humans into fish.

Two survivors of this flood safely made it to land and built a fire to cook themselves some fish. However, the smoke from the fire disturbed the stars in the sky above, and they complained to Tezcatlipoca. In response, the deity decapitated the pair and reattached their heads to their bottoms, thus creating dogs.

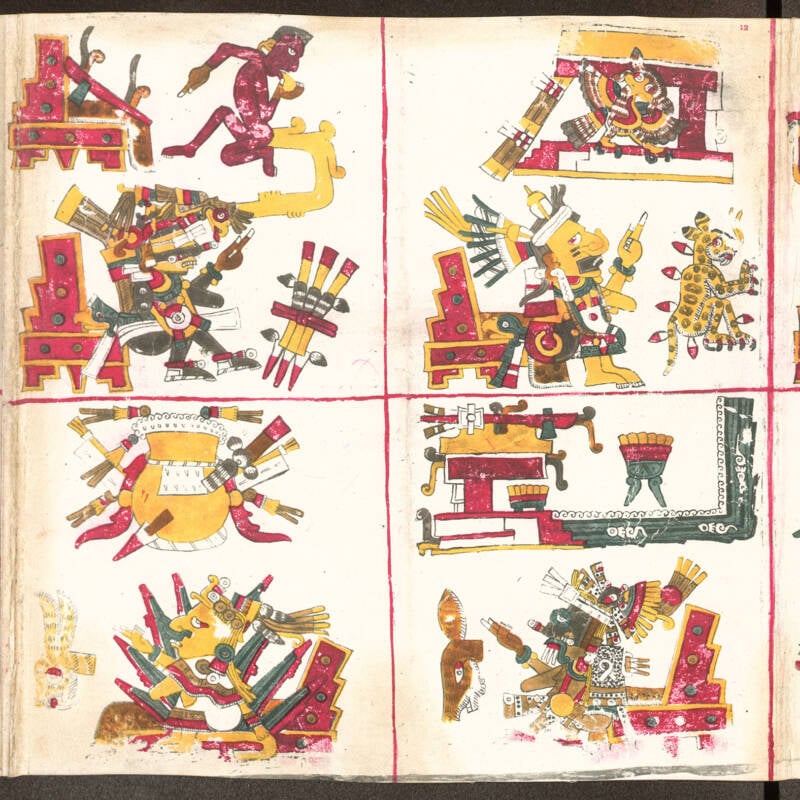

Public DomainTezcatlipoca (upper left panel) as portrayed in the 16th-century Codex Borgia.

Tezcatlipoca somewhat redeemed himself during the Fifth Sun, however. This final era — the current one, according to the myth — began with the sacrifice of the gods Nanahuatzin (or, in some versions of the tale, Xolotl) and Tecciztecatl, who became the Sun and Moon respectively. But the Sun and Moon remained motionless.

To set them in motion, many of the gods sacrificed their own blood, and in some versions of the myth, Tezcatlipoca was the first deity to offer himself up.

Naturally, there are many variations to these legends, but each consistently acknowledges the pivotal role Tezcatlipoca played in the formation — and destruction — of the worlds. His importance did not go unnoticed by the Aztec people.

How Tezcatlipoca’s Cult Celebrated The God Of The Night Sky

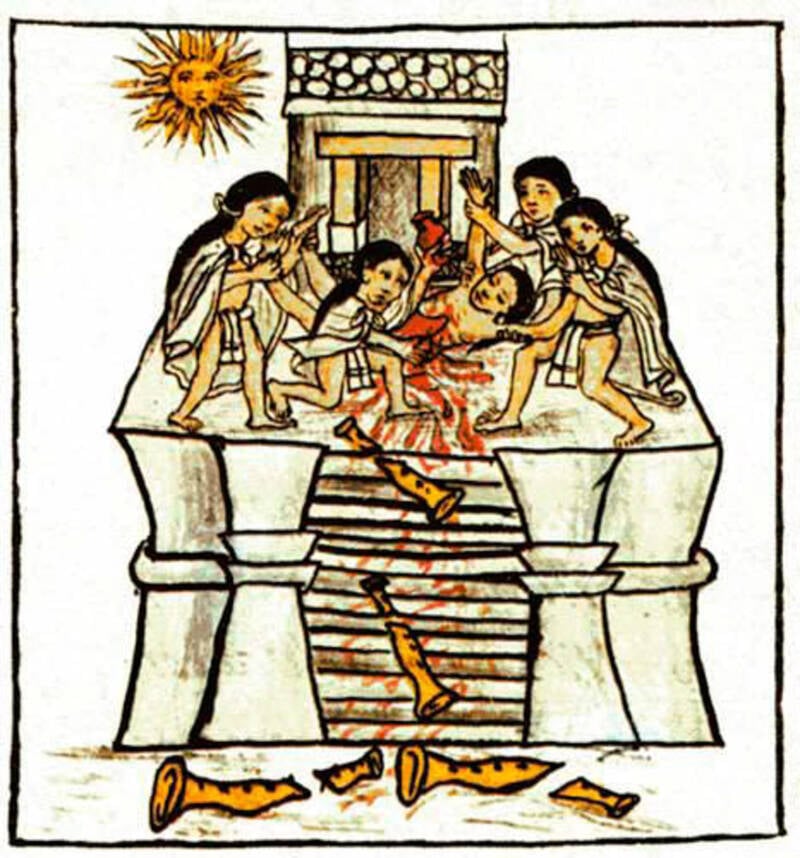

Historic Images / Alamy Stock PhotoA young man being sacrificed to Tezcatlipoca.

Worship of Tezcatlipoca and other Aztec gods was often a bit confusing. Legends suggest that each of these gods was their own distinct deity, though many were often siblings and, in many cases, considered “twins” of another deity. Other versions of the legends, however, cite a single, supreme deity who has several “manifestations” that take on different forms.

Some Mesoamerican cultures regarded Tezcatlipoca as this supreme omnipotent deity. According to the World History Encyclopedia, these manifestations were known as Black Tezcatlipoca, Blue Tezcatlipoca, Red Tezcatlipoca, and White Tezcatlipoca.

However, for the sake of clarity, these supposed manifestations could also be referred to as other gods. Black Tezcatlipoca, or the “Smoking Mirror,” is typically characteristic of the individual god Tezcatlipoca. Blue Tezcatlipoca is more commonly referred to as Huitzilopochtli. Red Tezcatlipoca, or the “Flayed One,” is most often known as Xipe Totec. And White Tezcatlipoca, the “Plumed Serpent,” can be seen as Quetzalcoatl.

It’s important to acknowledge this strange dual association, though, as it explains much about how Tezcatlipoca was worshipped.

The single most significant ritual dedicated to Tezcatlipoca was the Tóxcatl festival, held during the fifth month of the Aztec calendar. Preparations for the festival began a year in advance with the selection of a young man, often a captured warrior, who would impersonate Tezcatlipoca. Known as the ixiptla, this individual was seen as a physically perfect vessel for the god and treated as such.

Rik Hamilton / Alamy Stock PhotoA mosaic mask of the god Tezcatlipoca.

For a year, the ixiptla lived in luxury, adorned in fine clothing and jewelry and accompanied by attendants. The people, meanwhile, worshipped him as the god incarnate. He was also married to four young women representing goddesses.

Then, on the day of the festival, the proceedings took a macabre turn. The ixiptla would ascend the steps of a temple dedicated to Tezcatlipoca to be sacrificed by priests, who removed his heart using an obsidian knife. Though grisly, the sacrifice was considered a great honor.

However, the Tóxcatl festival would also become part of something far darker in the 16th century: the Tóxcatl Massacre.

The Tóxcatl Massacre And The Spanish Conquest Of The Aztec Empire

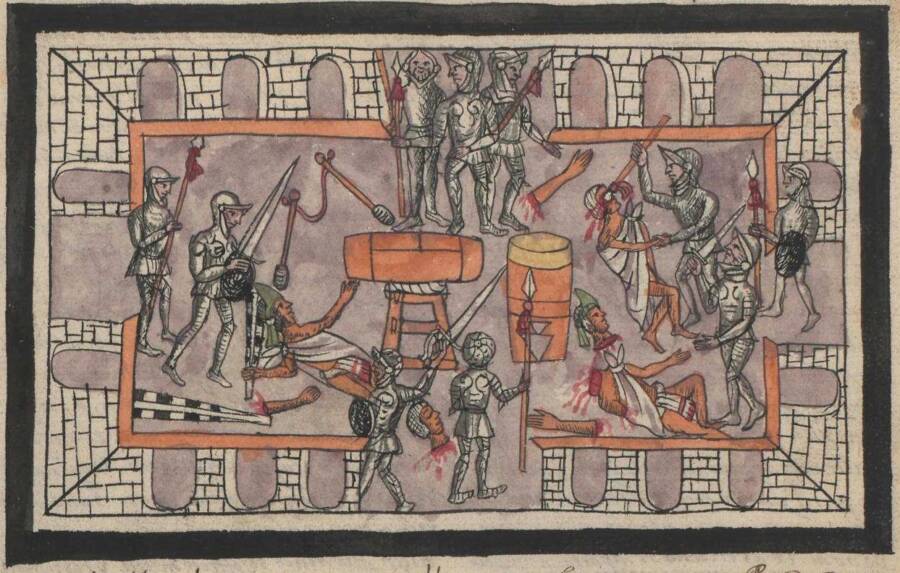

Given how important the Tóxcatl festival was to the Aztec people, it naturally drew a lot of attention from the Spaniards as they began to conquer much of the empire. Seeing the festival and its high number of revelers as an opportunity to further their own interests, the Spaniards struck.

But first, some background: In November 1519, Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés and his forces entered Tenochtitlan, where they were received by Emperor Montezuma II. However, tensions quickly arose when the Spaniards took Montezuma hostage with the express interest of controlling the Aztec leadership. Then, in April 1520, Pánfilo de Narváez launched his own expedition in the Aztec kingdom, forcing Cortés to leave Tenochtitlan under the command of his deputy Pedro de Alvarado.

Meanwhile, the Aztecs began to make preparations for the Tóxcatl festival with permission from Alvarado. Unfortunately, his intentions were not pure.

On May 22, 1520, Alvarado, fearing an uprising, mobilized his forces and massacred the unarmed participants gathered in the Great Temple of Tenochtitlan. Spanish soldiers blocked the exits and slaughtered numerous Aztec nobles, priests, and warriors.

Public DomainAn illustration of the Tóxcatl Massacre.

According to the Getty Museum, there are contrasting records of the event, with the Spaniards claiming they acted in self-defense — though, based on the conquistadors’ record, it’s more likely they were the instigators.

In either case, news of the massacre spread quickly throughout the Aztec empire, inciting widespread outrage. Eventually, that outrage became a full-scale rebellion against the Spanish occupiers. When Cortés returned, he found the city in turmoil and urged Montezuma to address his people and quell the uprising.

The people greeted Montezuma with hostility, and he died soon after under unclear circumstances. The escalating violence, however, forced the Spaniards to flee Tenochtitlan on June 30, 1520, an event now known as “La Noche Triste,” or the Night of Sorrows.

The massacre effectively shattered any remaining trust between the Aztecs and the Spaniards, and though they successfully forced the Spaniards out of the city then, the conquerors returned a year later and destroyed Tenochtitlan and its people. Thus, the Aztec empire — and the worship of Tezcatlipoca — came to an end.

After reading about the Aztec god Tezcatlipoca, learn all about Mictlantecuhtli, the Aztec god of the Underworld. Then, see inside the Templo Mayor, the Aztec temple of skulls that terrified Spanish conquistadors.