The 1996 film brought the late 20th century heroin epidemic to popular audiences. Here's what that epidemic looked like — and how it compares to the crisis today.

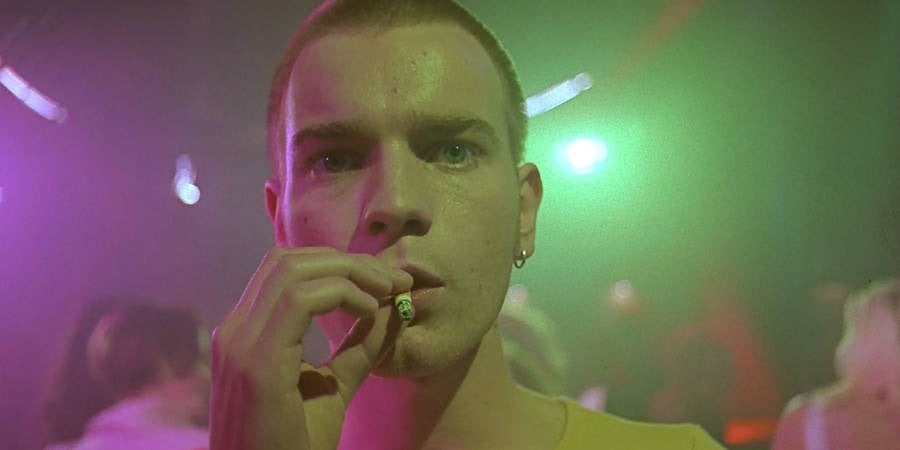

Movieclips Vault/YouTubeEwan McGregor in Trainspotting.

“Take the best orgasm you ever had, multiply it by a thousand and you’re still nowhere near it.”

This is how Mark Renton, the character played by Ewan McGregor in the cult classic Trainspotting, describes a heroin high.

It’s lines like that one — along with the film’s cast of handsome (in a pale, skinny, sickly kind of way), witty, and free-spirited characters — that provided the foundation for accusations that the film glamorized drug culture.

At the time of the Scottish movie’s release in 1996, U.S. Republican Presidential nominee Bob Dole pointedly attacked it for exaggerating the “romance of heroin.” And a critic from the Glasgow Herald described the film as “juvenile,” “inane,” “asinine,” and “puerile.”

But to this day, supporters of the film maintain something quite different:

Trainspotting (along with the novel on which it was based) was the first of its kind to depict a very real problem in a crucially realistic way.

While it purposefully describes the euphoria that comes with drug use — allowing viewers to question whether spending a day on opiates is any more wasteful of one’s life than mindlessly pulling levers at a factory — the narrative also shows the horrifying consequences of addiction: HIV, terrible pain, poverty, a neglected baby left to die in a crib.

“Hopefully, because of that complexity people trust it more,” director Danny Boyle told The Washington Post. “And if there is a message, people find that message more effective because of the honesty with which they’ve been addressed.”

Regardless of their big screen portrayal, young heroin addicts were an undeniable presence in the ’80s and ’90s, and they’ve grown up to be known as “The Trainspotting Generation.”

And just as fans gear up for the Trainspotting sequel, which will hit theaters in March, statistics show that the real-life heroin epidemic is making a comeback as well — with U.S. heroin-related deaths increasing by 248 percent since 2010, according to the Drug Enforcement Administration.

It’s telling, therefore, to take a look back on the population that inspired the original film: How they lived then, what their lives are like now, and how doctors, artists, politicians, young people, and parents alike might brace themselves for a real-life sequel.

What Caused It?

The late ’70s saw Europe in the midst of a crippling recession, growing ghettos, and record levels of joblessness. By 1982, more than 3 million people in the United Kingdom were unemployed (one in every eight).

These high levels of idleness and poverty were paired with a new wave of heroin imports from Iran and Pakistan.

With this increased supply, heroin — which had previously been confined to middle and upper class users in big cities — became more affordable, readily available, and in a new smoke-able form that appealed to users turned off by injection.

From the late ’70s to the early ’80s, the number of heroin addicts in the UK rose from between 10,000 and 20,000 to anywhere from 60,000 to 80,000, according to government records.

By the ’90s, there were hundreds of thousands of documented addicts — not to mention the many who stayed under the radar.

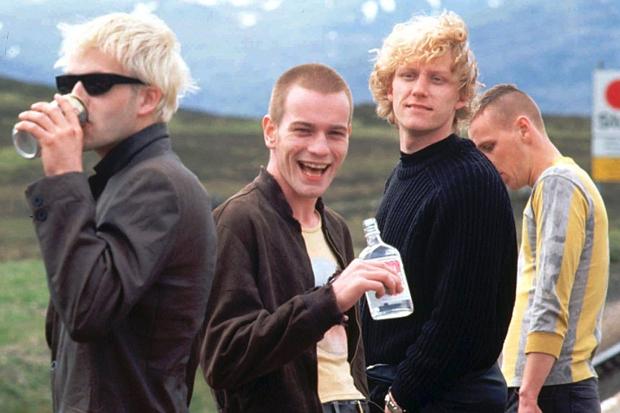

Movieclips Vault/YouTubeThe cast of Trainspotting.

What It Looked Like

Heroin found a home with the punk scene of the time: angry young people with nothing to do, who defined themselves by sticking it to the system that had screwed them over.

The average heroin user looked similar to the Trainspotting gang: young, unemployed and from working-class families in towns like Glasgow, Manchester, and Edinburgh — where the film was set.

They had crazy hair and piercings. Their clothes were purposefully ripped. They tried hard to show how little they cared about trying. They stole cars, TVs, and drugs — causing the national crime rate to increase by about 120 percent.

One study found that the mode age for heroin users in 1984 was only 19 years old.

Because almost everyone had first tried heroin at the urging of a friend or acquaintance, many of them didn’t even know what they were hooked on.

“I had teenagers who’d all left school together coming through the door jaundiced and with needle wounds asking for help,” said Roy Robertson, a professor who has run an Edinburgh treatment clinic since the ’80s. “When I asked them what drug they were taking they said they were on ‘smack.’ I asked them if they meant heroin and they said, ‘No! Smack.'”

They didn’t lead glamorous lives — as anyone who has known a heroin addict can attest to.

“Heroin addicts vomit a lot,” an Australian journalist wrote in 1996. “They get the runs. They watch a lot of terrible American television. They nod off. They are intrinsically boring.”

Still, many former users maintain that the drug made them happy.

“It was the best two years of my life, it was fantastic fun,” one man recently told Robertson of his time as an addict in a Scottish housing project named Leith. “I spent the whole time in Leith completely spaced out….No one cared — HIV had not been invented!”

Whether or not it had a name, though, HIV and AIDS rates exploded due to shared needles. In Edinburgh in particular, a staggering 50 percent of intravenous users were HIV positive by 1990.

Heroin Chic

Looking back, the carefree attitudes about the drug seem shockingly flippant. But mainstream culture and fashion propelled the “live fast die young” craze even further.

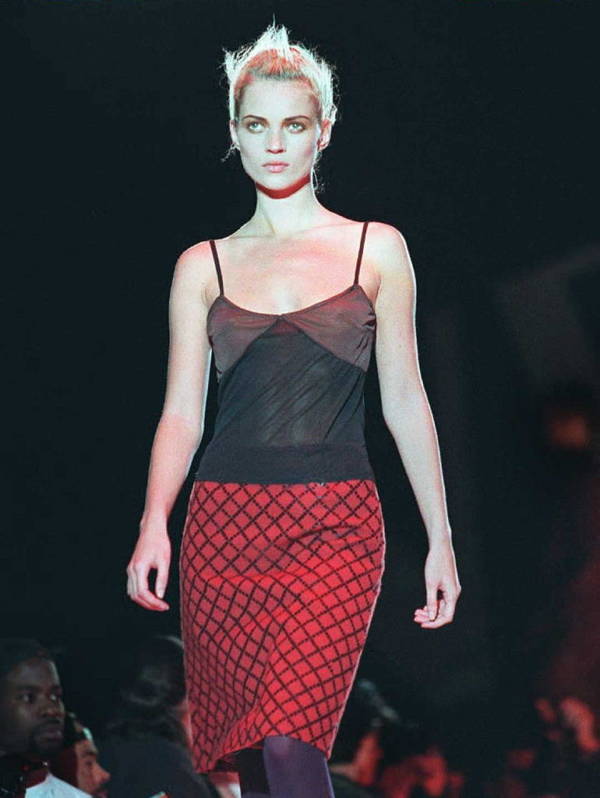

In 1996, a British fashion magazine called The Face published a spread that featured beautiful, bone-thin models in a police line-up. The dark makeup around their eyes mirrored the look of junkies, and the makeup on their inner arms suggested bruises from needles.

Kate Moss was then the international face of fashion — a face featuring frighteningly prominent cheekbones and eyes that seemed consistently unfocused and unfazed.

Jon Levy/AFP/Getty ImagesSupermodel Kate Moss in 1996.

Even then-President Bill Clinton noticed the trend as it spread across the Atlantic.

In 1997, he said that using drug imagery in mainstream media “is not creative. It’s destructive. It’s not beautiful. It is ugly. And this is not about art. It’s about life and death. And glorifying death is not good for any society.”

But the author of Trainspotting (the book), Irvine Welsh, argued that “heroin chic” wasn’t as much a cause of the problem as a reflection of it — a reflection that actually helped bring attention to a group of people society normally ignored.

“There is the bulk of heroin users, and then there’s a minor fluctuation on top, and that’s the high-society glitterati users, the pop-star addicts,” he told The Washington Post in 1996. “And when they disappear, heroin disappears from the newspapers, but there’s still that huge iceberg beneath the sea, people who have nothing to do with chic.”

Movieclips Trailers/YouTubeThe original cast filming the Trainspotting sequel.

How It Ended and Why It’s Coming Back

All epidemics end eventually, and the heroin boom of the ’80s and ’90s was no exception.

As unemployment decreased, investments in drug treatment increased and pop culture shifted to embrace a more optimistic youth. The drug recruited fewer and fewer new users from a generation that had the benefit of seeing the opiate’s long-term effects on the prematurely aged faces of their predecessors.

Many of the hundreds of thousands of people being treated for addiction today are the middle-aged survivors of the Trainspotting Generation.

A study from Edinburgh University found that one in four addicts from that time has since died of drug-related causes. One in three were still using heroin. Fewer than 20 percent were off of drugs completely.

The former users who have achieved sobriety lead “unremarkable lives,” working low paying jobs or living off benefits.

But in spite of these living and breathing warnings, the drug is still making a comeback.

The return makes sense, since government reports show that epidemics commonly ebb and flow every 20 years or so, when there is “a new susceptible youth population.”

The 21st century outbreak is most evident in America — where overdose deaths have increased five-fold in the last 15 years.

Drugs in the U.S. now kill vastly more people than car crashes or guns, and the numbers — 91 opioid overdose deaths a day — have surpassed the peak of the original epidemic 20 years ago.

The trend shows no signs of abating and officials are scrambling for a way to shift the tide.

And as young, angry, and largely lower-class Americans overdose in dollar store aisles, McDonald’s bathrooms, churches, parks, and libraries, the premiere of Transporting 2 may hit closer to home than many are prepared for.

Next, read about when heroin was considered “God’s Own Medicine.”. Then learn why the war on drugs was a spectacular failure.