Nearly 100 years after the tragedy, survivors and descendants of victims have not received any compensation for their suffering.

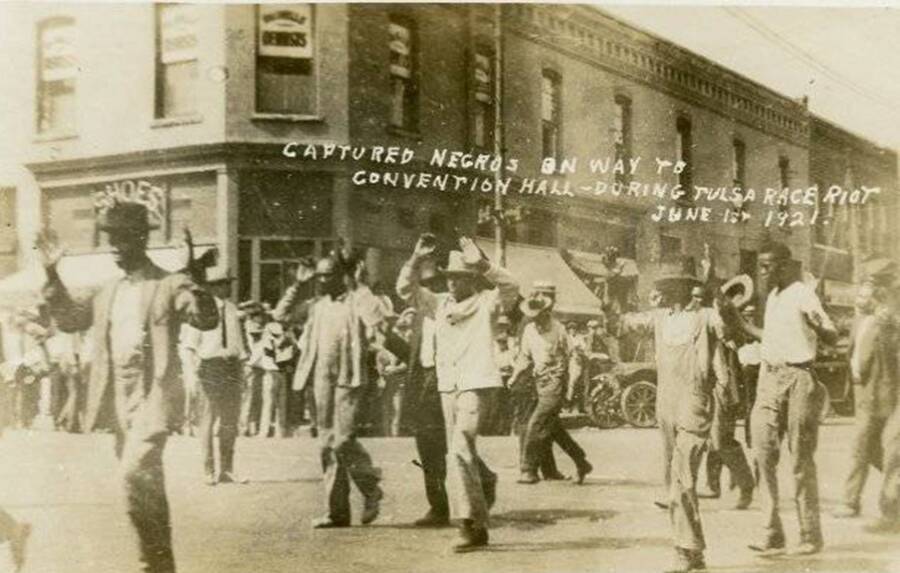

Tulsa Historical Society & MuseumBlack men being marched at gunpoint through the streets of Greenwood during the Tulsa massacre.

In 1921, one of the wealthiest Black neighborhoods in the U.S. known as Black Wall Street went up in flames. Shops and houses were burned down by a white mob that attacked the neighborhood and an estimated 300 innocent residents were killed in what is now known as the Tulsa Race Massacre.

Contemporary experts posit the number of victims could be even higher, but there’s no way to know for sure. Many of the dead were allegedly taken away and buried in secret spots around the city.

As America continues to reckon with racial injustice, advocates and residents of Tulsa — many whom are descendants of those who suffered during the riots — have spurred government efforts to identify the missing bodies. Now, Black residents are fighting for reparations.

According to the Guardian, a group of Oklahoma residents have filed a lawsuit to demand reparations for victims of the attack on Black Wall Street. Leading the fight is 105-year-old Lessie Benningfield Randle, one of the only two survivors of the Tulsa Massacre still alive today.

Randle’s childhood home was badly damaged during the tragic incident and has left the elderly woman with trauma that still remains even 100 years later. She still has flashbacks of dead bodies stacked up on the street in the midst of the burning neighborhood.

Randle, like many of the victims of the Tulsa massacre, has yet to receive compensation for their losses from the attack which the lawsuit alleges involved officials from the city of Tulsa, Tulsa county, and the Oklahoma National Guard and Tulsa Regional Chamber.

Randle herself was lucky to have lived long enough to see her old childhood home fixed up like new, but only through the goodwill of community advocates who raised funds and support for the repairs. These improvements were implemented in 2019 — 99 years after the tragedy.

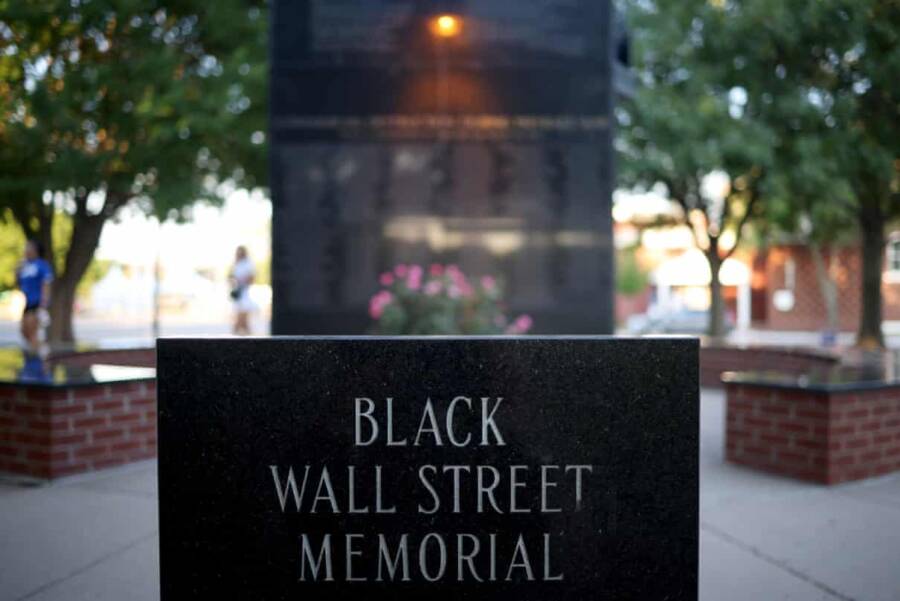

James Gibbard/Tulsa World

105-year-old Lessie Randle (right) is one of two survivors of the massacre who are still alive today.

“The Greenwood massacre deprived Black Tulsans of their sense of security, hard-won economic power and vibrant community,” said Damario Solomon-Simmons, one of the attorneys who filed the lawsuit on behalf of the plaintiffs.

Beyond the direct harm the incident had on Black residents, the lawyers contend that the financial fallout and racial implications contribute to ongoing challenges faced by the city’s Black communities.

“[It] created a nuisance that continues to this day,” Solomon-Simmons said. “The nuisance has led to the devaluation of property in Greenwood and has resulted in significant racial disparities in every quality of life metric — life expectancy, health, unemployment, education level, and financial security.”

Win McNamee/Getty ImagesA 2001 commission investigating the city’s involvement in the Tulsa massacre recommended reparations be paid to its victims.

A report by Human Rights Watch, an international non-profit focused on investigating human rights abuses, found that much of the poverty in Tulsa today is disproportionately concentrated to the Black neighborhoods around Greenwood. More than 35 percent of north Tulsa’s population, which is predominantly Black, lives in poverty compared with 17 percent in the rest of the city.

The irreparable harm caused by the Tulsa massacre is undeniable and there is evidence of city involvement. A 2001 commission formed by the state legislature found that the city had conspired with its white residents against Black residents and recommended direct payments to survivors and their descendants. But no payments were ever made.

The city has made increased efforts to identify and excavate the unmarked burials of missing victims and, in 2019, awarded medals to survivors of the massacre. But that is not the same as the reparations recommended by the commission.

It’s unclear how much reparations the lawsuit is asking for. But there may not be a right price to compensate for the lives that were lost, and those that are still buried in unmarked graves.

Next, take a look at 25 striking images that show the blunt racism that permeated the Reconstruction Era and learn about the Great Depression’s forgotten Black victims.