A descendant of Inca royalty, Túpac Amaru II led one of the bloodiest revolutions against Spanish colonization until his brutal execution in 1781.

Unknown/Wikimedia CommonsThe earliest known image of Túpac Amaru. Lima. C. 1784-1806.

Until his gruesome execution in 1781, Indigenous Peruvian leader Túpac Amaru II led one of the bloodiest revolutions in American history. Fighting against Spanish colonization, Amaru and his legion of Indigenous rebels sought to overthrow the Spanish and reinstate himself as the supposed descendant of the last Inca king, Túpac Amaru.

While he was unsuccessful, Amaru’s rallying cry echoed throughout South America, inspiring similar revolts. Indeed, his legacy was encapsulated in his alleged final words, “I will return, and I will be millions.”

Who Was Túpac Amaru?

Born José Gabriel Condorcanqui in Surimana, Peru, on March 19, 1738, Túpac Amaru II was the son of a local kuraka, or Inca magistrate responsible for liaising with the Spanish. As such, he received an education at a Jesuit school, an opportunity that Incas outside the elite would not have.

He also spoke Spanish and Quechua, also uncommon for an Indigenous Peruvian. His family claimed to be descended from Túpac Amaru I, the last leader of the Inca empire before Spanish colonialism. When he became an activist himself, he adopted the name in his family’s honor: Túpac Amaru II.

At a young age, Amaru inherited his father’s position as kuraka of the Tungasuca area in Cuzco province after his father died. He married Micaela Bastidas, who would become an important figure in the revolution in her own right, around the same time.

Overall, Amaru’s position as kuraka, as well as his contacts as a merchant and educated Inca, gave him a perfect vantage point to the abuses of the Spanish colonial system.

And he would not stand idly by.

Spanish Colonization And The Last Inca Leader

After Spain defeated the Inca Empire in 1532 and established the Viceroyalty of Peru in 1572, the Indigenous population there labored under the weight of two unjust economic systems: the repartimiento and the mita.

The repartimiento forced Indigenous populations to purchase goods from merchants at vastly inflated prices, while the mita forced communities to send laborers to work in the Potosí silver mines, notorious for their brutal conditions.

“This cursed and vicious reparto has placed us in this deplorable state of death with its immense excess,” Túpac Amaru himself wrote to the top royal official in Cuzco. He added that owners “look upon us as worse than slaves, make us work from two in the morning until the stars appear after nightfall.”

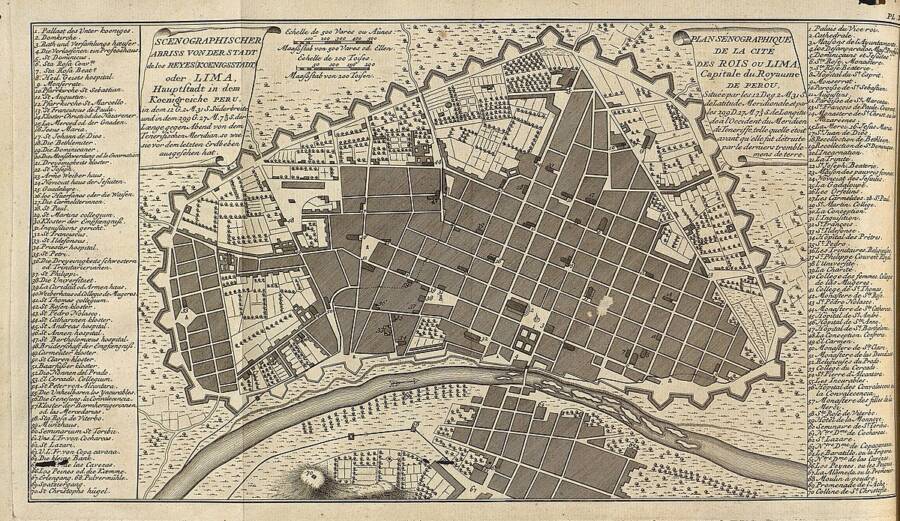

Antonio de Ulloa and Juan Jorge/Wikimedia CommonsA 1750 map depicting Lima, Peru, the capital of colonial Peru and a major Spanish power center.

On top of that, Spain’s distant monarchy imposed the Bourbon Reforms in the 1760s and 1770s. Those reforms increased taxes and customs regulations, much to the Indigenous population’s ire.

Therefore, the conditions were ripe for a charismatic leader to incite a major revolt, especially after two prior rebellions failed.

With his rhetoric and symbolism harkening back to the heights of Inca rule, Túpac Amaru would be that leader.

The Rebellion Sweeps The Andes

On Nov. 4, 1780, Amaru attended what one podcast called the “worst dinner party in world history.” That’s because Amaru kidnapped Spanish Governor Antonio de Arriaga from there and imprisoned him.

Six days later, Túpac Amaru ordered Arriaga’s execution — and his own slave would perform the deed.

After executing Arriaga, Túpac Amaru spread his economic plan throughout the Andes. He would abolish numerous taxes against Indigenous populations and slavery, and trade Spanish law and order for Inca law and order. Amaru also smashed textile mills and redistributed their production, echoing an ancient Inca tradition.

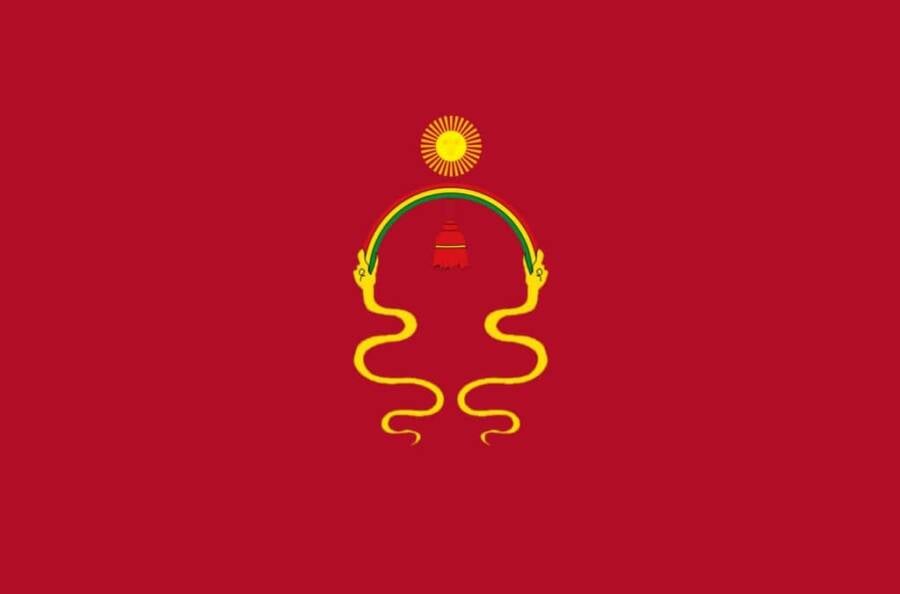

Alejandro Vasombrio/Wikimedia CommonsA modern-day reimagining of Túpac Amaru’s flag.

Several days later, Amaru attacked Sangarará in the first major military victory for the rebellion. There, the Spanish holed up in the local church “with vain confidence, and against all good judgment,” according to a contemporaneous Spanish observer.

But Amaru’s forces had the advantage and quickly took victory. In unclear and still disputed circumstances, the town’s church burned down, adding insult to injury for the Spanish — and turning many against the rebels.

“This sad event gave the rebels sufficient wings to speed ahead with their exploits,” the same observer wrote. Subsequently, Amaru romped through the Andean highlands from his base at Tungasuca.

Túpac Amaru II’s Last Stand On Cuzco — And Horrifying Death

His next target? Cuzco, the former Inca capital.

But Túpac Amaru II seemingly took his time in mounting an offensive, not actually attacking until Jan. 4, 1781, despite besieging the city since December 1780.

The rebel force appeared formidable. One observer remarked that the hills surrounding Cuzco resembled a “porcupine back” from the rebel army.

Although Amaru found initial success, the royalist forces soon pushed his army back. Even “the dregs of the plebes, feeble women” contributed to the city’s defense. By January 10, Amaru’s forces had all but abandoned the siege.

After their victory, royalist forces began to pursue Amaru himself.

In March 1781, Túpac Amaru’s forces routed the royalist troops, almost decimating the royalist column at a place called Pucacasa. The rout made Amaru overconfident; he dropped his guard.

In April, a defector in Amaru’s camp convinced their leader to wait in a place called Langui. There, a militia captured him. He was brought back to Cuzco in shackles.

On May 18, 1781, Spanish forces executed Túpac Amaru II in a brutal manner.

First, they forced him to watch as executioners hanged his wife, sons, and top lieutenants. Then, they cut out his tongue, tied ropes to his arms and legs, and had horses pull his body apart. In a final irony, they set a bonfire on the hill where he led the siege of Cuzco.

Helder Ribeiro/Wikimedia CommonsA sculpture depicting the execution of Tupac Amaru in Quito, Ecuador. 2007.

The royal representative José Antonio de Areche also ordered punitive measures against Inca culture. He banned traditional clothing, traditional religion, plays criticizing the Spanish government or glorifying Inca tradition, and even a particular history book believed to have influenced the rebel.

Although Túpac Amaru II’s death marked a seemingly mortal blow to the rebellion that bore his name, it did not stop his designated successors — mostly young and inexperienced rebels — from continuing the rebellion in his name.

Indeed, the rebellion continued for another year until mid-1782, when Tupac Amaru’s successors signed a cease-fire with royalist forces.

Meanwhile, Túpac Catari — who drew his name from Túpac Amaru — led a similar revolt that besieged La Paz, Bolivia, around the same time as Amaru’s execution.

Like Túpac Amaru’s siege of Cuzco, that revolt failed as well.

The Inca Rebel’s Legacy Today

Although the colonial administration attempted to extirpate Inca culture, that effort failed. Indeed, the policies that Areche promulgated in his 1781 edict were “draconian” and would have required immense resources to carry out.

Despite those Spanish efforts, Inca culture remained alive and well. However, Tupac Amaru’s memory almost remained silent, left out of the history books.

Rodolfo Pimentel/Wikimedia CommonsA statue of Túpac Amaru in the Fortaleza del Real Felipe in Callao, Peru. 2012.

“There are liberators … whose growing sideburns between their old uniforms declare them national heroes,” lamented Peruvian poet Antonio Cisneros. “Others, without so much fortune, occupied two pages of text with four horses and his death.”

But leftist revolutionary governments in the 1960s and 1970s revitalized his image, especially under General Juan Velasco Alvarado’s rule in Peru. Additionally, the Tupamaro guerrilla movement in Uruguay took on his mantle as it terrorized that country’s military leadership.

And in the midst of that, a Black American mother named her child after the Peruvian rebel leader. That child would grow up to be one of the most famous rappers in the world: Tupac Shakur.

After learning about Túpac Amaru II and his rebellion, read about another famous South American liberator, Simón Bolívar. Then, learn about the Haitian Revolutionary Toussaint Louverture.