For centuries, Vikings traveled from throughout Scandinavia to join the elite Varangian Guard that protected the Eastern Roman Emperor and the city of Constantinople.

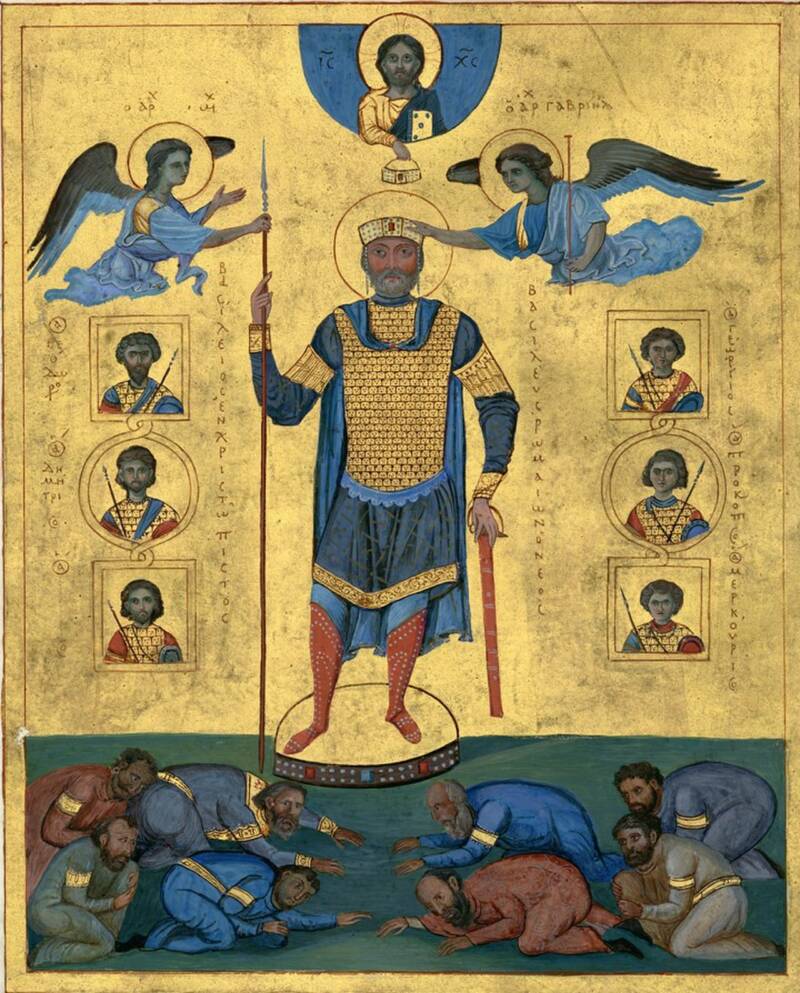

National Library of SpainA 12th-century illustration of the Varangian Guard defending Constantinople.

Vikings are perhaps best known for plundering Western Europe and being the first Europeans to set foot in North America. But they also played a crucial role in the Byzantine Empire, where a select group of warriors called the Varangian Guard protected the emperor in Constantinople for hundreds of years.

Loyal, fierce, and armed with a double-sided ax, these warriors patrolled the halls of the Great Palace, accompanied the emperor to war, and kept order in the streets. They were extravagantly rewarded for their service, and one of them even became the king of Norway.

Like many elite soldiers, the Varangian Guard eventually fell victim to shifts in power. But for hundreds of years, they reigned as some of the world’s most fearsome fighters.

The Formation Of The Varangian Guard

At the dawn of the Viking age around 800 C.E., most Vikings — a disparate group of Nordic warriors — stormed the shores of England. But some of them went east. Lured by Arabic silver, they sailed down the rivers of eastern Europe, plundering as they went.

Some of these Vikings settled in Eastern Europe. They were called Rus, or Kievan Rus, which roughly translates from Old Norse as “ones who row.” They grew in power, and their leaders started taking on Slavik names.

Around 978-980, a dispute arose between the sons of Prince Sviatoslav I of Kyiv. To fight his brothers, Vladimir I of Kyiv called up 6,000 warriors from nearby Sweden. Not only did these soldiers help him conquer the region, but they also laid the foundation for the Varangian Guard.

Дар Ветер/Wikimedia CommonsVladimir of Kiev converted to Christianity and lent his powerful Varangian Guard to the Byzantine emperor.

Less than a decade later, Basil II of the Byzantine Empire reached out to Vladimir for military aid. He needed help to defeat two would-be usurpers to his throne. Basil offered his sister’s hand in marriage to sweeten the pot — as long as Vladimir was willing to convert to Christianity.

Vladimir agreed to send his warriors. As for Christianity, he’d long been looking for a religion to “modernize” his people, and he had decided against Islam because of its restrictions on alcohol.

“Drinking is the joy of the Rus, we cannot exist without that pleasure,” Vladimir allegedly said.

He became a Christian and dispatched his 6,000 Norse warriors to Constantinople, where his fearsome army soon became known as the Varangian Guard.

How Vikings Protected The Byzantine Empire

Public DomainA depiction of Basil II of the Byzantine Empire.

The Varangian Guard made an impact as soon as they arrived. According to historian J.J. Norwich:

“In late December 988 the Black Sea lookouts espied the first of a great fleet of Viking ships on the northern horizon… and 6,000 burly giants disembarked. A few weeks later, the Norsemen, led by Basil himself, crossed the straits under cover of darkness.

“At first light they attacked… [swinging] their swords and battle-axes without mercy until they stood ankle-deep in blood. Few of the victims escaped with their lives.”

Another account of the Varangian Guard’s attack noted that the Vikings “cheerfully hacked [their enemies] to pieces.”

After Basil had crushed his enemies, he decided to keep the Vikings around. Soon, they were being called Varangians, likely from the Old Norse word vár which meant “confidence (in),” “faith (in)” or “vow of fidelity.” It loosely translates to “men of the pledge.”

The Varangians became Basil’s bodyguards, acted as police and jailers, and accompanied the emperor to war. And the fearsome Varangian Guard left an impression everywhere they went. Arab traveler Ahmad Ibn Fadlan marveled that he’d “never seen bodies as nearly perfect as theirs.”

Fadlan wrote that the warriors were “tall as palm trees, fair and reddish, they wear neither tunics nor kaftans. Every man wears a cloak with which he covers half of his body, so that one arm is uncovered. They carry axes, swords, daggers and always have them to hand.”

And a Byzantine chronicler characterized them as “frightening both in appearance and in equipment,” adding, “they attacked with reckless rage and neither cared about losing blood nor their wounds.”

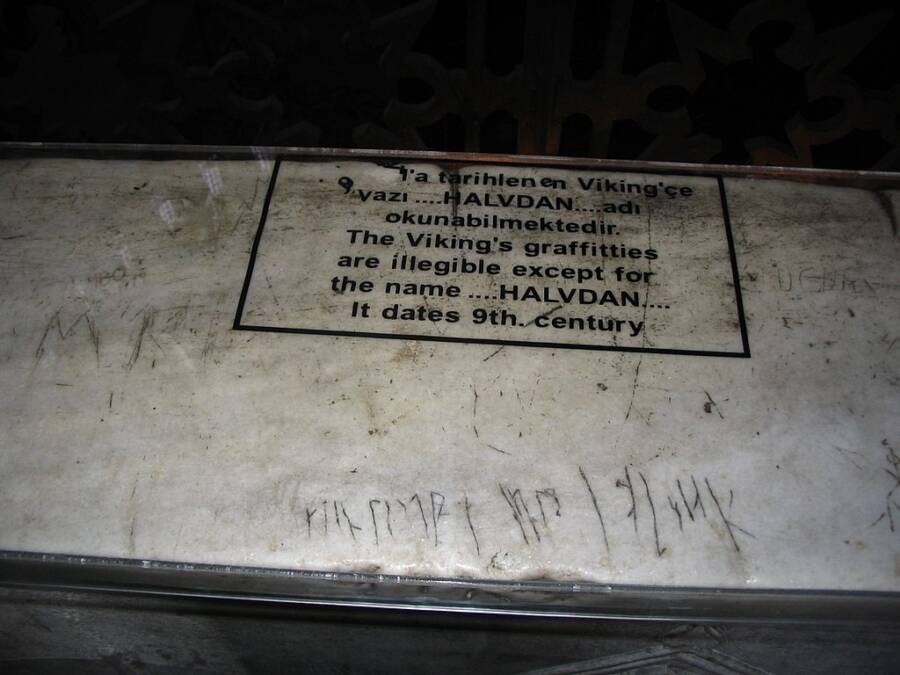

Sometimes, their job wasn’t that exciting. The Vikings stood guard at the majestic Hagia Sophia, where one warrior grew so bored that he carved his name into the marble.

Wikimedia CommonsGraffiti left by a likely member of the Varangian Guard, which reads “Halfdan,” probably his name.

But for others, serving in the emperor’s elite force paved the way toward wealth and power. Harald Hardrada, who’d fled Norway for Kyiv after his half-brother’s failed bid for the throne, served in the Varangian Guard from 1034 to 1043. He amassed so much wealth as a warrior that he returned to Norway and became king.

Likewise, a warrior named Bolli Bollason ended his tour with the guard as a wealthy man. According to the Laxdaela Saga, Bollason came home wrapped in purple robes embroidered with gold. His awed countrymen referred to him as “Bolli the Elegant.”

Indeed, according to Old Norse sagas, many warriors returned home dripping with jewelry and expensive silks. In part, that’s because a strange law allowed them to plunder the emperor’s treasury whenever he died.

“On the night of their sovereign’s death, they had the curious right to run to the imperial treasury and take as much gold as they could comfortably carry,” explained historian L. Brownworth. “This custom enabled most Varangians to retire as wealthy men.”

Serving in the Varangian Guard — if you survived — seemed a sure way to riches.

Yet the days of the Varangian Guard were numbered. Though they fought bravely and fiercely, their power began to decline in the 11th century.

The Transformation And Fall Of The Byzantine Varangian Guard

The world of Varangian Guard underwent sweeping, dramatic changes over the centuries. After the Norman Conquest in 1066, in which William the Conquerer overtook England, exiled Anglo-Saxon warriors went in droves to Constantinople. Their presence changed the makeup of the warriors.

Vivaystn/Wikimedia CommonsA painting of the fall of Constantinople at the Panorama 1453 History Museum in Istanbul.

And the inexperienced new members of the guard faced new, fierce foes. They were defeated while defending Dyrrachium in Dalmatia in 1081, and they weren’t able to suppress the forces of the Fourth Crusade in 1204. Then, the weary warriors may have laid down their arms when they saw that the Byzantines were defeated.

From that point on, the Varangian Guards spent most of their time standing watch over palaces or prisons, not fighting in actual conflicts. Their numbers dwindled. And they became obsolete when Ottoman Sultanate conquered Constantinople in 1453, heralding the end of the Byzantine Empire.

By then, most of the Varangian Guard were Anglo-Saxon, anyway, not Norse.

But for hundreds of years, they shone as a strange, frightening presence on the streets of Constantinople. Tall, fair, and armed to the teeth, these Viking warriors changed the course of history when they took up arms for the Byzantine Empire.

Though their glory days may have faded from the history books, traces of these warriors endure in Constantinople itself. The graffiti scratched into the Hagia Sophia, just a couple of simple runes, acts as an echoing reminder of the Varangian Guard’s once-ubiquitous presence in the city.

After reading about the Varangian Guard, learn about the Praetorian Guard, the fearsome military unit of ancient Rome. Then, discover the story of the terrifying Viking warriors called Berserkers who fought nude.