As Joseph Stalin's chief executioner of the NKVD, Vasily Blokhin is believed to have personally ended tens of thousands of lives.

Wikimedia CommonsMajor General Vasily Mikhailovich Blokhin killed tens of thousands of people at Stalin’s command.

For decades, citizens of the Soviet Union lived in constant fear of secret police organizations empowered to dole out punishment. Beyond the threat of imprisonment or exile, the dreaded elite executioners posed a terrifying threat. Of these professional mass murderers, Vasily Blokhin boasted the highest body count.

Rising to prominence within the shadowy ranks of the secret police, Blokhin became an instrument of death in Joseph Stalin’s numerous purges and in the brutal repression which lay at the foundation of the Soviet empire. Though his killing spree began in the 1920s, Blokhin’s most gruesome achievement came during World War II.

Over just 28 days in the spring of 1940, he was personally charged with planning the execution of over 20,000 Polish prisoners of war. Blokhin shot as many as 7,000 prisoners personally, one by one, cementing himself as one of the most prolific individual killers in world history.

This is the chilling story of Vasily Blokhin, the Soviet Union’s bloodiest executioner.

Vasily Blokhin’s Murky Beginnings

Little is known about Vasily Blokhin’s early years. Born in 1895 to peasants in the countryside near the city of Vladimir, he went to work as a shepherd at the age of ten before moving to Moscow to become a bricklayer.

By June 1915, the Russian Empire was deeply entangled in World War I. Blokhin joined the Imperial Russian Army and likely saw combat in Belarus. Eventually, he rose to a senior noncommissioned officer rank.

Wikimedia CommonsRussian troops marching to the front, circa 1917.

In 1917, conditions at home took an unexpected turn. Tsar Nicholas II was toppled in the February Revolution, sending shockwaves throughout the army and the Russian Empire. A provisional government that supported free speech rights and other liberal beliefs led by lawyer Alexander Kerensky was briefly installed in the Romanov Tsar’s place.

However, that fall, the Bolsheviks, a Communist faction, seized power in St. Petersburg. Their control of the country was nowhere near total, and in order to respond to both peaceful political dissent and violent opposition from the monarchist White movement, the newly-formed government decided that a police force with almost unlimited powers would be needed.

Blokhin, wounded in 1918, returned home to work on his father’s farm. He waited to see which faction would emerge as the victor.

In May 1921, Vasily Blokhin made his political choice: after joining the Communist Party, he was immediately appointed to the ranks of the already-feared “All-Russian Extraordinary Commission,” better known as the Cheka — the first of many iterations of the secret police in the Soviet Union.

Blokhin’s Role In Cheka, The Secret Police

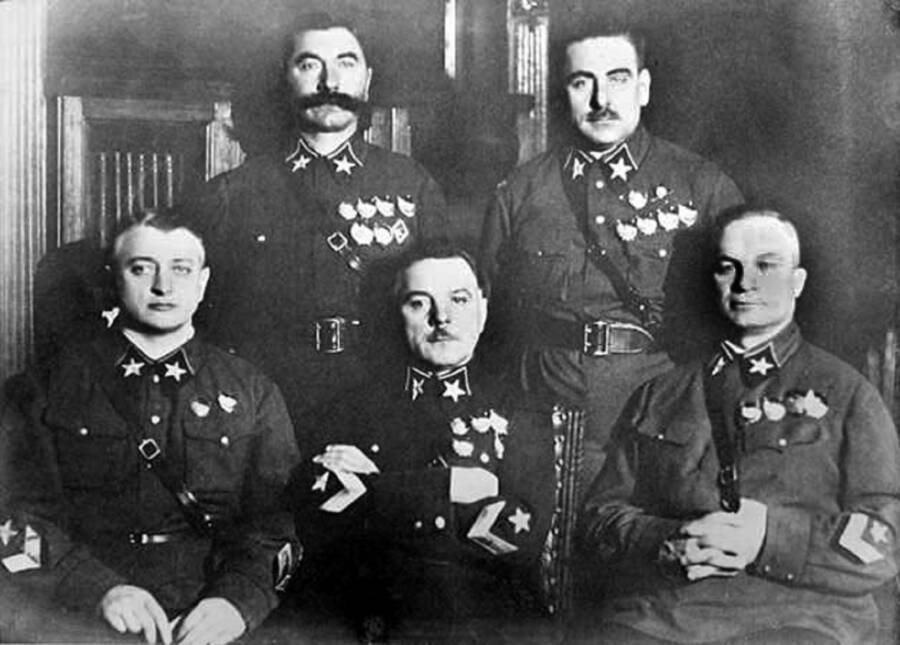

Wikimedia CommonsMarshal Mikhail Tukhachevsky (bottom right), was one of Vasily Blokhin’s highest-profile victims during the Great Purge of the 1930s.

Chekists were entrusted with ensuring discipline in the new Red Army, protecting shipments of food and supplies, and disrupting opposing political groups through violence and infiltration.

Blokhin took an active part in the Cheka mission, quickly gaining the attention of his superiors. He steadily climbed the ranks and in 1926 was appointed “Commissioner of the Special Department of the OGPU” — in other words, chief executioner.

His ascendancy dovetailed with that of Joseph Stalin, who became increasingly powerful in the 1920s, as well as the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) which came into being between 1917 and 1922.

Blokhin was tasked with carrying out and supervising executions in the Lubyanka building in Moscow, which held prisoners on its top floor with Cheka offices below.

Wikimedia CommonsThe Lubyanka was a symbol of dread for Soviet citizens. Here, Vasily Blokhin and his fellow executioners killed thousands.

The preferred method of execution at the Lubyanka was crude. The condemned was ordered to kneel. Then, the executioner fired a bullet into the back of their skull. The body was then moved to a crematorium of Blokhin’s own design, inaugurated in October 1927 to commemorate the Bolshevik Revolution’s tenth anniversary.

During Stalin’s Great Purge which took place between 1936 and 1938, some 750,000 people were executed as dissenters. Blokhin personally shot the victims of the great show trials, as well as several of his fellow executioners when they fell under suspicion.

Blokhin’s abilities won him the personal favor of Stalin. When bureaucrats accused Blokhin of conspiring against the state in 1939, Stalin refused to sign a warrant for his execution, calling the “black work” Blokhin did invaluable.

The purges had largely ended by the time Nazi Germany and the USSR cooperatively invaded Poland in September 1939. But for the Soviets, angered by their defeat in the Polish-Soviet War of 1919-20 and eager to smash any resistance to their power in Eastern Europe, the invasion was only the beginning.

The instrument of their violent goals was to be the Cheka, now renamed the NKVD.

The Massacre At Katyn

The capture of eastern Poland delivered thousands of Polish soldiers, officers, officials, and intellectuals to the Red Army — all of whom were distrusted by Lavrentiy Beria, the new head of the NKVD.

Beria had come to power after toppling his predecessor Nikolai Yezhov, who may have been personally shot by Vasily Blokhin. To Beria, every Polish officer was a potential threat to the Soviets, and the solution he proposed to Stalin was as brutal as it was simple: execute every officer who couldn’t be convinced to join them. Stalin quickly greenlit the bloody plan.

Universal History Archive/Getty ImagesPhoto from the 1943 exhumation of a mass grave of Polish officers.

In the spring of 1940, over 22,000 soldiers, writers, bureaucrats, police officers, and politicians were shipped to sites in western Russia, including the Katyn forest near the city of Smolensk, for execution.

In charge of the organization, Vasily Blokhin and two colleagues traveled to the outskirts of the town of Ostashkov to take part, outfitting a soundproof hut and setting themselves a quota of 300 executions a night.

Victims would first be taken to an antechamber of the hut that had been painted red and dubbed “the Lenin room” for identification. Then, they were handcuffed and taken to the execution room where Blokhin was waiting with his gun. On the very first night of the massacre, Blokhin and his colleagues shot 343 victims, a grisly accomplishment for three men working only with pistols.

Years later, ex-NKVD officer Dmitry Tokarev described how Blokhin, who’d brought a suitcase of reliable German Walther PP pistols to carry out his task instead of the standard-issue Soviet TT-30 which he found unreliable. He dressed in a butcher’s leather apron with arm-length gloves, a long leather coat, and a leather cap to protect his uniform from bloodstains.

But perhaps the eeriest thing about Blokhin was his calm, cheery demeanor. Top Soviet executioners lived under a kind of mental torture themselves. They rarely saw their families and often drowned the trauma of killing with alcohol.

Blokhin, by contrast, was a strict teetotaller, preferring hot sweet tea even on the killing fields of Katyn, and his cheerful attitude in all situations and settings made him universally popular among his fellow black work operatives.

Wikimedia CommonsThe bound hands of one of the 22,000 victims of the Katyn massacre.

“An experienced executioner shoots in the neck, holding the barrel obliquely upwards,” Blokhin stated matter-of-factly. “Then there is a chance that the bullet will come out through the eye or mouth. If you kill 250 people a day, then cleaning the premises becomes a serious problem.”

At the end of 28 days, all but a few hundred of the captives had been shot and buried in mass graves. Blokhin himself claimed to have personally shot as many as 7,000. As a reward, he received a small raise, a gramophone, and the Order of the Red Banner, one of the highest military awards in the USSR.

Before taking a month’s vacation, he and his fellow executioners held a banquet behind a train station just down the road from the site where they’d carried out their brutal task.

The Nazis — no strangers to horrifying violence themselves — uncovered the mass graves from the Katyn massacre when Germany invaded the Soviet Union in late 1941.

Wikimedia CommonsAn examination of exhumed soldiers in 1943.

Rumors of a massacre near Smolensk led German troops to the graves in Katyn, and Nazi Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels knew he’d uncovered something he could use against the Soviets. In April 1943, he organized a media circus around the exhumation of the bodies, including a Red Cross delegation, a forensics team, radio coverage, and even journalists from occupied nations, who were released from detention to report the discovery.

However, the Soviets claimed that the Germans were responsible for the mass killings at Katyn. Soviets pointed to the fact that the victims in the mass graves had been shot with German guns to support their story. Other Allied leaders were somewhat skeptical of this narrative, but to avoid rocking the boat with Stalin they accepted the Soviet version of events.

Is Vasily Blokhin The Most Prolific Killer In History?

Wikimedia CommonsThe ashes of countless people killed by Vasily Blokhin are buried in this common grave, just a short walk from Blokhin’s own in Moscow’s Donskoye Cemetery.

Even among the notoriously violent NKVD members of Stalin’s day, Blokhin stands out, with as many as 20,000 deaths credited to him. Over the course of a quarter of a century, he’d personally shot notable army generals, artists, and old revolutionaries.

Because of the secrecy of most Soviet executions, his true death toll may never be known — but Blokhin certainly has one of the highest victim counts for any executioner in history. According to his claim, he killed twice as many as runner-up Peter Maggo — another Soviet executioner who’s believed to have killed more than 10,000 people.

The deaths of Stalin and Beria in 1953 signaled Blokhin’s downfall. Stripped of his rank and honors, he sank into alcoholism before dying by suicide in 1955. His name was forgotten by much of the world until 2010 when the Russian government finally admitted guilt in the Katyn massacre.

That same year, Vasily Blokhin was named as the Guinness World Record holder for the most prolific executioner as his role in the Katyn massacre had finally come to light.

Even in death, Blokhin can’t escape his brutal past. Just a short walk away from his grave in Moscow’s Donskoye Cemetery lies Common Grave Number 1. This morbid pit was the NKVD’s preferred dumping ground for the cremated remains of Blokhin’s victims after passing through his special crematorium.

After learning the terrifying truth behind the Soviet Union’s bloodiest killer, take a closer look at what life was like inside the Gulag in these tragic photos. Then, explore Russia’s forbidden closed cities that were built to hide the Soviet nuclear program.