In Renaissance-era Venice, Veronica Franco reached unusual heights for a woman as an educated courtesan. But as luxurious as the position was, it could be easily destroyed.

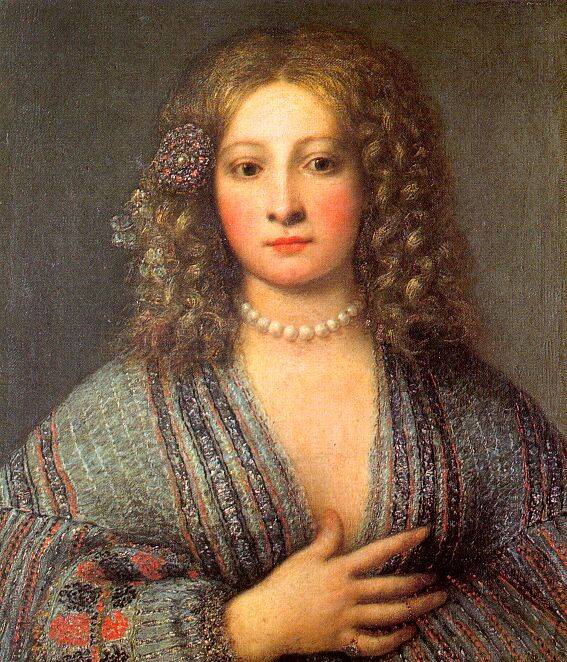

Jacopo Tintoretto/Museum of Fine Arts of LyonThe elegant nude figure in this painting is supposedly Veronica Franco, who was renowned for her intellect.

To contemporary onlookers, it seemed that 16th-century courtesans like Veronica Franco lived a gilded life of luxury. But Renaissance women, even courtesans like Franco who had powerful patrons, were vulnerable.

In her time, Franco was known as a cortigiana onesta or an “honest courtesan.” The title recognized intellectual women who were revered as much for their minds as they were their bodies among the Venetian elite.

For many years, Franco successfully navigated the difficult world of Renaissance sex work — until one of her employees accused her of witchcraft, leading to a trial before the feared Venetian Holy Inquisition.

Veronica Franco Impressed The Venetian Elite

Jacopo Tintoretto/Worcester Art MuseumJacopo Tintoretto painted this portrait of a lady thought to be Veronica Franco in 1575.

When Veronica Franco was born, the role of Renaissance courtesans often went beyond sex work. Many were considered intellectuals — and Franco was one such woman.

In the half-century before Franco was born, Venice boasted around 12,000 prostitutes out of a total population of 100,000 people. Additionally, under a 1542 law, any unmarried woman who had sex with anyone or accepted gifts from men was considered a prostitute, and women who fell into that legal category faced extra restrictions. For example, they couldn’t go to church on feast days or wear silk or gold jewelry.

But Venice placed courtesans in a unique category. They weren’t wives or daughters who were meant to be protected by male relatives, nor were they nuns who were to be shut away from the world in an effort to focus on heavenly pursuits. Instead, courtesans like Franco were public women who enjoyed more independence than other women.

Veronica Franco was born to an honored courtesan named Paola Fracassa in 1546 and was trained in the profession as a child. She also received an unconventional education through a private tutor that had been hired to teach her three brothers.

She was unusually knowledgable for a woman of her time and this was quickly recognized by Venice’s male aristocrats.

Though Franco was married off to a doctor in the early 1560s, the marriage dissolved shortly afterward and the courtesan was free to socialize with the city’s elite. Throughout the 1570s, Franco frequented Venice’s literary salons where she met wealthier men who commissioned her to write sonnets. She published an anthology in 1575, though the collection also included some poems by the man who financed it.

Franco even corresponded with King Henry III of France, Duke Guglielmo Gonzaga of Mantua, and Cardinal Luigi d’Este. In fact, when King Henry visited Venice on his way to his coronation in 1574, the city hired Franco to entertain him. The pair spent a night together, about which Franco later penned sonnets.

In Franco’s day, an ordinary courtesan could garner further clout through publication. Her poetry anthology was therefore an enormous triumph that helped to elevate her status.

On the surface, Franco’s life was certainly better than the cortigiana di lume, or the lives of lower-class prostitutes who waited for clients beneath the Rialto Bridge.

But Franco nonetheless struggled to survive in a world that relegated women to narrow roles and often used the guise of religion to punish them when they garnered too much power.

The Life Of Luxury Comes At A Price

The Elisha Whittelsey Collection/The MetFerrando Bertelli’s flip-up print of a Venetian courtesan showing off her high heels in 1563.

In some ways, Venetians saw courtesans and prostitutes as a necessary evil. They were tolerated both to protect “honest women” from attack and because the sex industry generated tremendous tax revenue for the government.

In addition to intellectuals and sex workers, courtesans of Franco’s time were considered trendsetters who pushed the boundaries of fashion. Some donned 20-inch heels known as chopines to show off on Venice’s streets. Most wore luxurious outfits that made them look like noblewoman and sometimes donned men’s breeches underneath or even exposed their breasts.

Pearls were the choice adornment for courtesans, and in spite of the many laws that restricted what women could wear, courtesans often defied the rules.

But the life of a courtesan was a double-edged sword. Despite the access they were afforded, they had few legal protections. As Franco wrote, being a courtesan put women at the mercy of their patrons and thus left them vulnerable to exploitation.

“To become the prey of so many, at the risk of being despoiled, robbed, killed, deprived in a single day of all that one has acquired from so many over such a long time, exposed to many other dangers of receiving injuries and dreadful contagious diseases… What greater misery?”

For all the outward glamour of a courtesan’s life, it was nonetheless a precarious position in society.

Veronica Franco Is Subjected To The Inquisition

Girolamo Forabosco/UffiziA 17th-century painting of a Venetian courtesan.

In fact, Veronica Franco’s trial captures the delicate existence of intellectual courtesans.

All it took for Franco’s fragile status to crumble was an anonymous accusation of witchcraft in 1580. Franco was consequently hauled before the Venetian Holy Inquisition, a tribunal created by the Venetian government and the Catholic Church to sniff out heresy, and forced to defend herself against a panel that was ready to see her executed.

Giacomo Franco/The MetA Venetian woman with a dog, circa 1590.

The “anonymous” accusation came from a man named Ridolfo Vannitelli, whom Franco had hired to tutor her sons. Vannitelli brought several charges against Franco, including that she practiced witchcraft, played forbidden games, and made pacts with the devil to cause merchants to fall in love with her.

He also attacked her popularity: “She enjoys too much support in this city and is favored by many who should hate her.”

According to some historians, Vannitelli’s attempt to defame Franco was likely due to her accusing him of stealing some of her jewelry. She allegedly even brought the case before the Venetian government to Vannitelli’s dismay.

In the 16th century, witchcraft was a serious accusation and often led to a series of debasing and inhumane witch tests to determine whether the accused was indeed a servant of the Devil. During the witch trials, as many as 60,000 accused witches lost their lives. Many of those executions took place between 1570-1630, the height of Europe’s witch hunt.

The Venetian Inquisition, devoted to rooting out magic and Protestantism, which were both seen as major threats to the city, targeted Venetians accused of love magic, necromancy, and other illegal practices.

The Inquisitor asked again and again whether Franco had called upon the devil in her rituals. She denied everything. The trial lasted for two days. Eventually, Franco was acquitted of all charges.

The Revered Courtesan Dies In Poverty

Moretto da Brescia/Tosio Martinengo Gallery

The Venetian courtesan Tullia d’Aragona as Salomè.

Franco’s final years were difficult. Her reputation was damaged by Vannitelli’s accusations; the second outbreak of the black plague between 1575 and 1577 left her impoverished, and one of her most faithful patrons died in 1582.

Franco was thus forced to spend her last years in a Venetian neighborhood known for its destitute prostitutes. She died at age 45 in 1591.

Although courtesans were able to publish their writings and attend salons, they lived dangerous lives — and it didn’t take much for them to lose everything.

As Franco wrote in one of her poems:

And the less freedom we have,

the more our blind desire, which drives us off the path,

will find a way to penetrate our heart;

so that a woman either dies from this

or moves away from the restricted life that we all share

and owing to a small mistake is led far astray.

The “restricted life” of a Renaissance courtesan might have appeared dazzling from the outside, but courtesans like Veronica Franco knew the hard truth.

After reading about Veronica Franco, learn about Cora Pearl, a courtesan to 19th-century royalty. Then, learn more about the history of prostitution.