On June 19, 1982, a Chinese American man named Vincent Chin was clubbed to death by two white men in Detroit. His killers didn't spend a single day in jail.

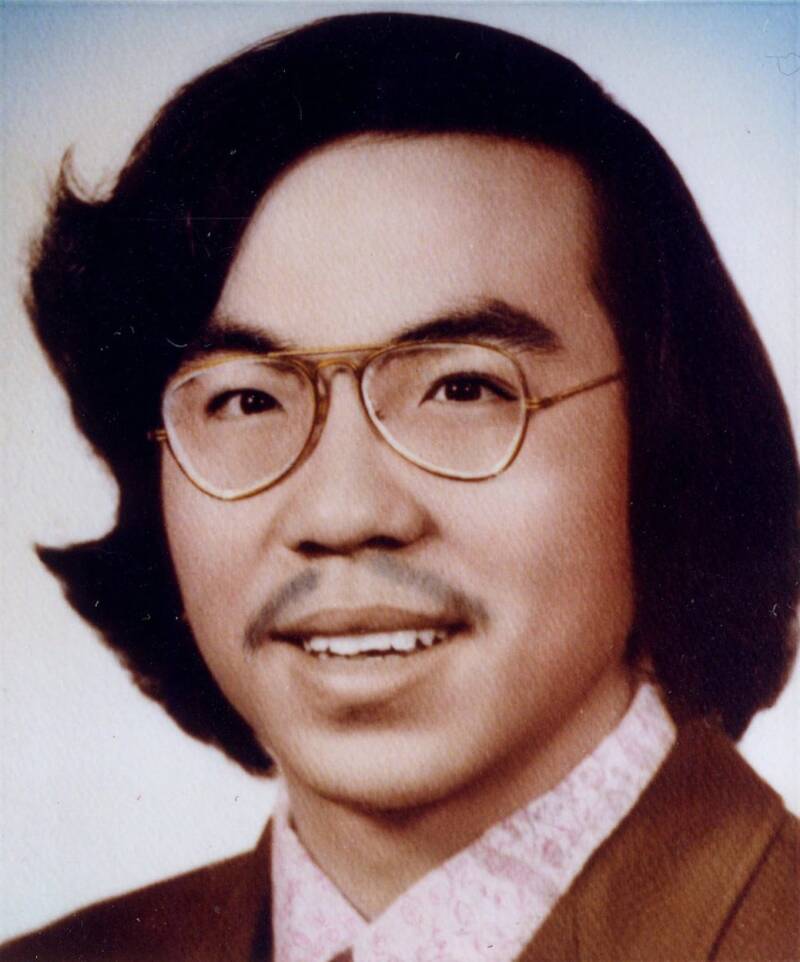

Chin family photoVincent Chin was a week away from getting married.

On June 19, 1982, the future looked bright for 27-year-old Vincent Chin. In 10 days, he was going to marry Vickie Wong, his girlfriend of three years. He had a good job as a draftsman for a top Detroit automotive supplier, and he was also working part-time at a Chinese restaurant to save up for a house.

That night, however, Chin would be gruesomely beaten by a pair of white men who blamed him for their lost jobs — and he would later succumb to his wounds on the day he was due to be married.

The sentences for Chin’s killers were almost unimaginably light, given what they admitted to doing. However, the incident became a galvanizing moment for Asian American civil rights and how hate crimes were viewed in the United States — in a way that resonates to this day.

The Night Vincent Chin Was Murdered

After a slow day at the restaurant, Vincent Chin went home early and decided to arrange an impromptu bachelor party. A devoted only son, he lived with his mother. His father, a World War II veteran, had died the year before. Chin had dinner and then told his mother that he was going out.

He met up with friends Robert Sirosky, Jimmy Choi, and his best man, Gary Koivu. They had a few drinks and then brought a bottle of vodka to Highland Park’s Fancy Pants Lounge, which didn’t serve alcohol because they had nude dancers. It was a boisterous night, with the four having a rowdy good time doctoring their sodas and throwing money at the performers.

Google Street ViewFormer site of the Fancy Pants Lounge, pictured in 2018.

On the other side of the stage, Ronald Ebens and his stepson, Michael Nitz, resentfully watched the women flock around Vincent Chin. Ebens was a Chrysler superintendent and Nitz was a laid-off autoworker. According to testimony by one of the dancers who was nearby, Ebens bitterly remarked, “It’s because of you little motherf—ers that we’re out of work.”

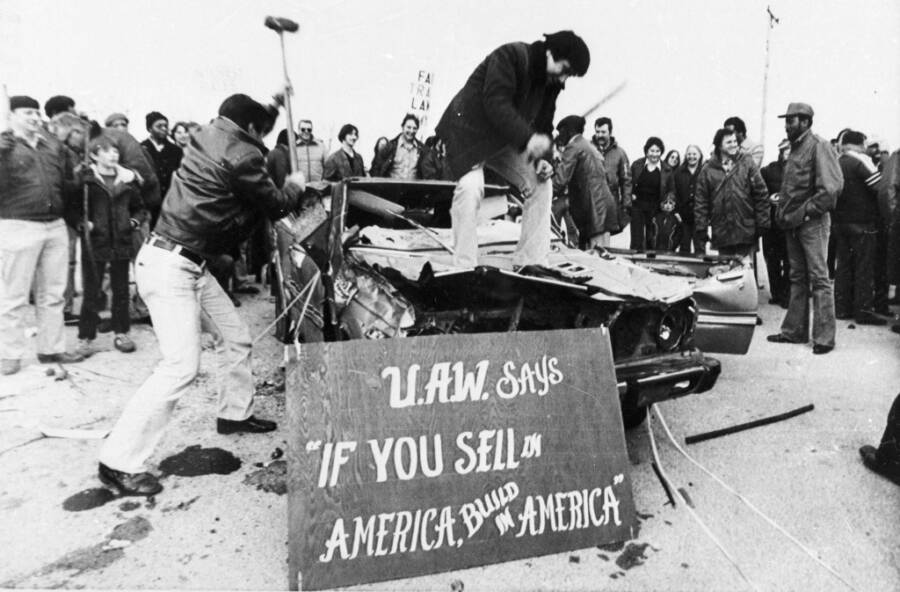

This was Detroit, a one-industry town, and in 1982, that industry was in its death throes. Many blamed Japanese imports instead of admonishing the Big Three (General Motor, Ford, and Chrysler) for the devastating de-industrialization that was costing so many their jobs.

And Ebens and Nitz assumed that Vincent Chin, a Chinese American, was Japanese.

Associated PressMembers of the United Autoworkers Local 588 wield sledgehammers and bars on a Toyota Corolla during a rally in 1981 against buying foreign-made products.

Chin protested, “We’re not Japanese!” as Ebens and Nitz allegedly spewed racial taunts. Chin finally climbed over the runway and decked Ebens.

There was a scuffle, which ended when Nitz was hit in the head with a chair, although accounts differ on who threw it. A bouncer broke up the fight and escorted Nitz and Ebens into a backroom for bandages, while Chin and his party left.

It could’ve ended there, and Chin would be celebrating his 39th wedding anniversary this year. Instead, violence ensued. After Nitz was bandaged up, the pair again encountered Chin in the parking lot, where Chin called Nitz a “chickens–t” — and Ebens responded by pulling a baseball bat from his car. He chased both Chin and Choi out of the parking lot, then hopped into the car with Nitz and gave chase.

They found the two Chinese American men catching their breath in front of a McDonald’s. Nitz held Chin down as Ebens whaled on him with the baseball bat, breaking several ribs. Chin struggled free and ran for it, but slipped and fell. Ebens caught up to him and cracked his head open.

Two off-duty policemen moonlighting as security guards at McDonald’s flashed their badges and demanded that Ebens drop his weapon.

One of the officers would later testify that Ebens was beating Chin with the bat like he was swinging “for a home run”.

Chin’s last words before slipping into unconsciousness were, “Fight. Fight. It’s not fair.” An EMS technician later said that it didn’t look like Chin would make it — there were “brains lying on the street.”

Ebens and Nitz were arrested and later charged with second-degree murder, while for the next four days, Chin’s fiancée and his mother held his hand while he lay in a coma. When brain activity ceased, they took him off life support. The guests who’d planned to be at his wedding attended his funeral instead.

Asian Americans Fight For Justice

Getty/Bettman ArchiveRonald Ebens enters federal court in 1984. Ebens and his stepson, Michael Nitz, both pleaded guilty to a reduced charge of manslaughter in Vincent Chin’s beating death.

The homicide was reported in the Detroit Free Press but it didn’t attract much attention nationally. Asian Americans whispered about it among themselves and quietly mourned. It was only after the trial that outrage led to action.

On March 16, 1983, Ebens and Nitz appeared in the Wayne County courthouse. They had taken plea bargains, reducing their charges to manslaughter. The prosecuting attorney, who was supposed to represent Chin’s family’s interests, didn’t even make an appearance — likely because the plea deal had already been struck.

Circuit Judge Charles Kaufman found Ebens and Nitz guilty of manslaughter and fined them $3,000, plus $780 in court costs for the killing of Vincent Chin. They walked off with probation for three years.

The lenient sentences outraged the Asian American community. Kin Yee, president of the Detroit Chinese Welfare Council, asserted that the sentences amounted to “a license to kill for $3,000.”

“These aren’t the kind of men you send to jail,” Kaufman later said in defense of the sentences. “We’re talking here about a man who’s held down a responsible job for 17 or 18 years, and his son is employed and is a part-time student. You don’t make the punishment fit the crime, you make the punishment fit the criminal.”

He concluded, “Had it been a brutal murder, of course these fellows would be in jail now.”

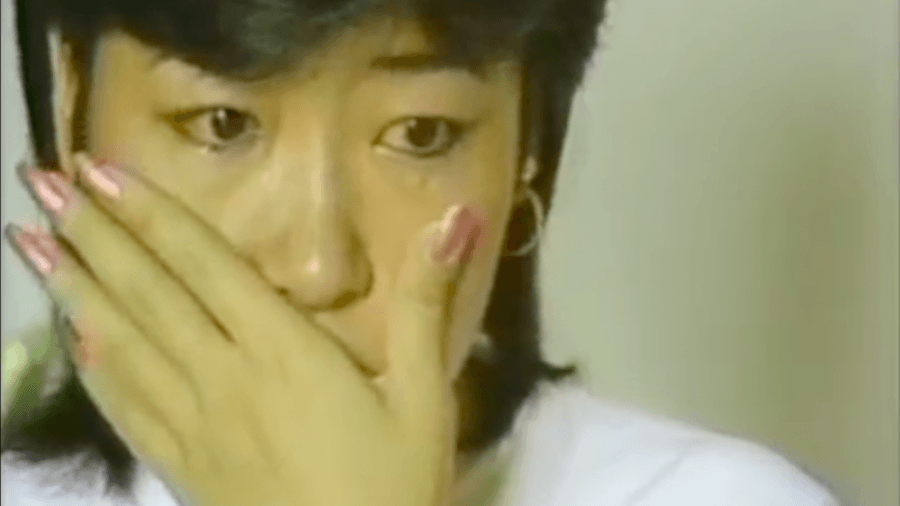

YouTubeVincent Chin’s fiancée Vickie Wong breaks down as she talks about Chin’s death in the documentary Vincent Who?.

Before Vincent Chin’s death, the term “Asian American” had not yet become mainstream. There were Chinese Americans and their struggle against the Chinese Exclusion Act. There were Japanese-Americans who had their own history of being unconstitutionally interned during World War II. There were Vietnamese-Americans and Filipino-Americans and Indian-Americans, all with their separate experience of racism in America. But these disparate groups had never united in a common struggle.

With Chin’s murder, the pan-Asian community realized that they were in it together. Chin was killed because of anti-Japanese scapegoating, even though he wasn’t Japanese — “You all look alike” suddenly took on an even darker meaning.

After the verdict, Asian Americans of every background rose up under the rallying cry, “Remember Vincent Chin.” Within a month, a pan-Asian American civil rights organization called American Citizens for Justice was formed by journalist Helen Zia and other activists in Detroit.

The Struggle For Asian American Rights

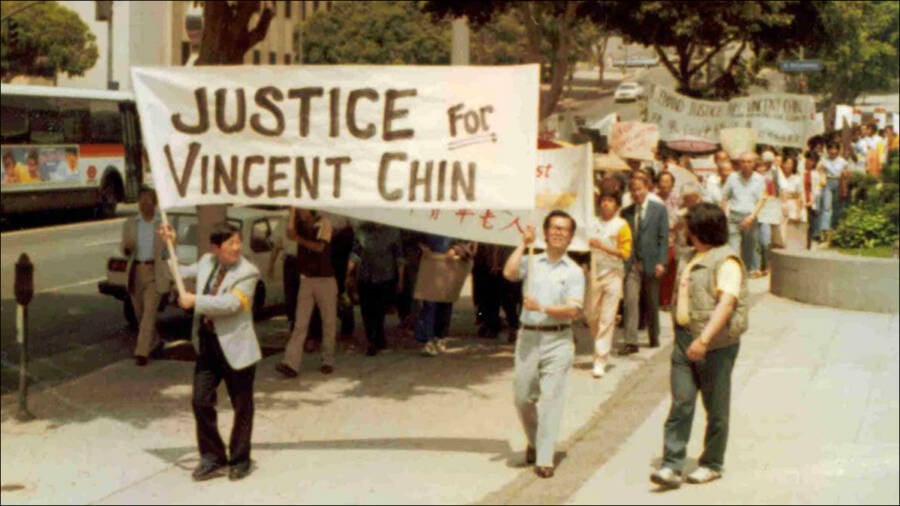

Asian Americans For Equality Asian Americans for Equality protest against the verdict in the Vincent Chin case.

At first, the ACJ met with resistance. According to Wayne State University constitutional law professor Robert A. Sedler, there was contention at the time as to whether Asian Americans were protected under civil rights laws. Neither the Michigan ACLU nor the Detroit chapter of the National Lawyers Guild thought at the time that Chin’s murder was racially motivated.

But the movement couldn’t be stopped — not with Chin’s mother, Lily, traveling across the country, tearfully begging for justice. Finally, Judith Cummings, a Black writer who was visiting relatives in Detroit, wrote an article that appeared in the New York Times. Suddenly, the case was on the Phil Donahue show and on television news across the country.

Christine ChoyLily Chin speaks at a news conference in 1983 in San Francisco’s Chinatown.

With so much publicity, the ACJ successfully petitioned the U.S. Department of Justice to investigate Chin’s murder as a civil rights violation. At the second trial in 1984, the U.S. District Court acquitted Nitz, but Ebens was found guilty of one count of violating Chin’s civil rights. He was sentenced to 25 years in prison.

However, in 1986 Ebens appealed his case and the conviction was overturned by an appeals court. One of Ebens’s lawyers told the New York Times that a prosecution witness had been coached. Ebens requested a retrial in a different location because of the animosity against him in Detroit. By then, he had been laid off by Chrysler and said no one would hire him.

The case was transferred to Cincinnati, where a federal jury of 10 white and two Black people found him not guilty of violating Chin’s civil rights. He never spent a day in jail and continued to assert for years that Chin’s death was an accident.

The Legacy Of Vincent Chin’s Murder

Asian Americans Advocating JusticeHundreds march from Los Angeles’ Chinatown to City Hall in 1984 to demand justice for Vincent Chin.

Lily Chin was distraught, “What kind of law is this? What kind of justice? This happened because my son is Chinese. If two Chinese killed a white person, they must go to jail, maybe for their whole lives … Something is wrong with this country,” she said. Heartbroken, in 1987 she moved back to China.

Though the legal battle was lost, Vincent Chin’s legacy lives on. The documentary Who Killed Vincent Chin? was nominated for an Academy Award in 1989. Other films, plays, articles, and artwork followed. The landmark trial established the legal precedent that Asian Americans were entitled to civil rights. This, along with increased dialogue between ethnicities, has led to stronger organization in the pan-Asian community.

But the fight is far from over. According to many experts and historians, Asian Americans are still saddled with the “model minority” stereotype — that they are all successful and don’t encounter racism. Some people even question whether Asian Americans are people of color.

Among themselves, Asian Americans struggle with internalized racism, a century of traumatic experiences with the American justice system, and cultural notions of propriety – all of which can add up to silence. But Chin’s death remains a visceral reminder of the need for marginalized communities to stand up. Today, “Remember Vincent Chin” continues to reverberate.

After this look at the murder of Vincent Chin, learn about how Anna May Wong battled bigotry in Golden Age Hollywood. Then, find out how Yuri Kochiyama survived an internment camp, then befriended Malcolm X and fought for civil rights.