"The only reason I'm here is because I had been messing around with a white lady," Walter McMillian said from death row.

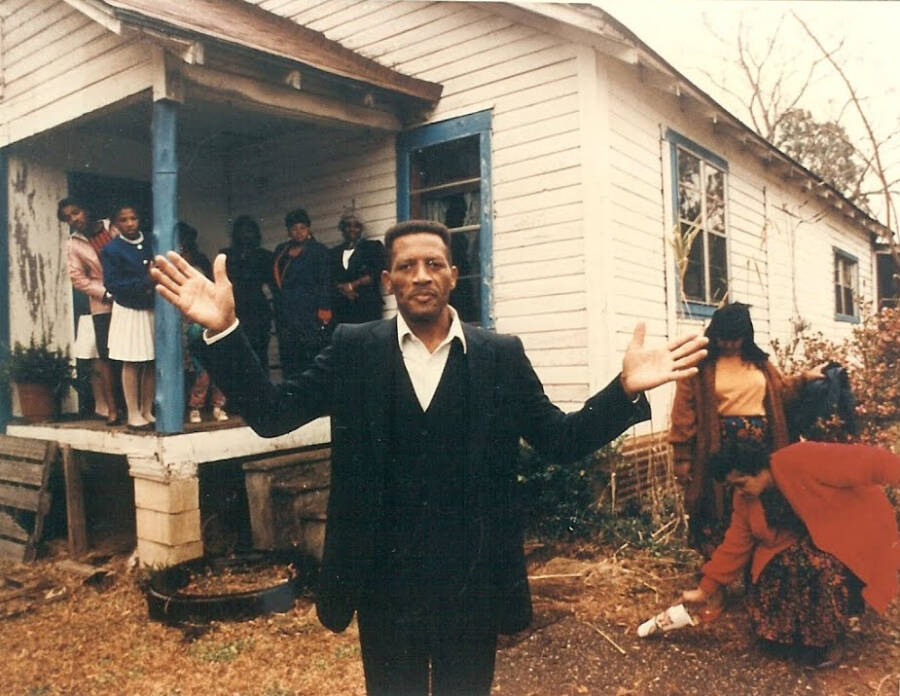

Equal Justice InitiativeWalter McMillian spent six years on Alabama’s death row for a murder he didn’t commit.

When Walter McMillian was a 12-year-old black boy in Monroe County, Alabama — where Harper Lee set To Kill a Mockingbird — a bullet-riddled black man was found hanging from a tree in nearby Vredenburgh.

The man was Russell Charley. He was a family friend, and the rumor was that he’d been lynched for dating a white woman.

Decades later, McMillian found himself the object of one pretty white woman’s flirtation. Things would be fine, he thought, as long as everything was kept secret. But when the word got out about their affair, he grew worried.

Less than two years later, he was convicted of murder — a murder he didn’t commit.

“The only reason I’m here is because I had been messing around with a white lady,” he told the New York Times from death row.

This is the true story of Walter McMillian, the wrongfully convicted man behind the film Just Mercy.

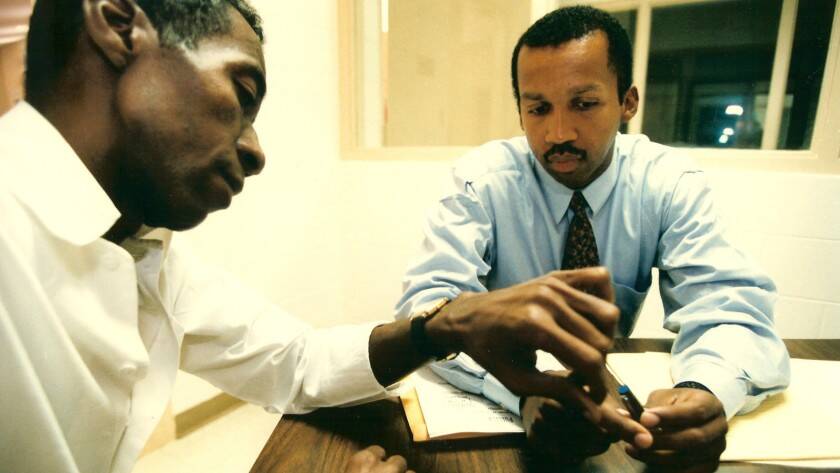

Financial TimesWalter McMillian (left) and Bryan Stevenson after McMillian’s conviction was overturned in 1993.

Growing Up In The Segregated South

Born on Oct. 27, 1941, McMillian grew up in one of several poor black settlements outside Monroeville. He picked cotton with his family, went to the local “colored school” for a couple of years, and then went back to picking cotton at around age eight or nine.

To him and his family, the money he got from picking cotton was worth a lot more than an education.

By the 1950s, however, cotton became less profitable, and the state of Alabama helped many white farmers transition to growing and chopping timber. When McMillian reached adulthood, he noticed this trend and borrowed money to buy his own equipment; by the 1980s, he owned a modestly profitable pulpwood business.

Equal Justice InitiativeWalter McMillian with his family after his release from prison.

McMillian and his wife, Minnie, met when when they were teenagers and married after she became pregnant in 1962. They had three children and lived in a dilapidated house in Repton, about 10 miles south of Monroeville.

As a gregarious guy who owned his own business — rare for a black man in the area — McMillian was a bit of a local celebrity. And that’s how his affair with a white woman 18 years his junior became the talk of the town.

He met Karen Kelly, who was 25 and unhappily married, at the Waffle House where he ate breakfast. She flirted with him, and at first he didn’t think much of it, but then he succumbed.

As Bryan Stevenson, McMillian’s future lawyer, wrote in his memoir Just Mercy, “‘Tree work’ is notoriously demanding and dangerous. With few ordinary comforts in his life, the attention of women was something Walter did not easily resist.”

Jamie Foxx plays Walter McMillian in the film, Just Mercy.

They had an affair, and when Kelly’s husband found out, things took a turn. He wasn’t just enraged that his wife was cheating on him — she was cheating on him with a black man.

This was Alabama in 1986. It was the last state in the U.S. to overturn laws banning interracial marriage — but that wouldn’t happen for another 14 years. Sexual or romantic relationships between blacks and whites were still very much taboo, especially out in the land of forests and plantations.

Kelly’s husband called McMillian to testify in their divorce proceedings. He was subjected to graphic questions about the nature of his and Kelly’s relationship, and he left the courtroom feeling uneasy.

Police Find Their Scapegoat In Walter McMillian

Weeks later, at around 10:45 a.m. on Nov. 1, 1986, 18-year-old Ronda Morrison — a white college student who was beloved by the local community — was found dead at a Monroeville dry cleaners, where she worked part-time.

She was shot three times in the back, and it looked like money had been taken from the cash register.

Seven months passed and every one of the police’s leads went nowhere. There was a new county sheriff, and people were whispering about his incompetence.

But then police arrested Ralph Myers, a white man with a drug problem and a lengthy criminal record who was also a new friend of Karen Kelly’s, McMillian’s ex.

Myers was picked up for a different murder, that of a poor white woman named Vickie Pittman. In his police interview, he made up all sorts of wild stories, like how the sheriff of a nearby county murdered Pittman. The police wouldn’t buy it, and so Myers said he had information on the Morrison case. He implicated not just himself, but McMillian as well.

In a taped confession, Myers said he drove McMillian to the dry cleaners on the morning of Nov. 1, 1986, but McMillian entered the building alone. Myers heard “popping sounds,” and he found McMillian standing over the victim with a gun in his hand.

HBOWalter McMillian (left) meets with his attorney, Bryan Stevenson.

Police were skeptical that Myers and McMillian were really accomplices, and so they conducted an experiment. They brought him to a store where McMillian and a few other black men were shopping, but Myers couldn’t tell which one was his supposed partner-in-crime; he had to ask the store’s manager to identify him.

He then slipped him a note, supposedly written by Karen Kelly, but McMillian looked confused and threw the note away.

It was clear that Myers and McMillian didn’t know each other; Myers’ word was the sole evidence connecting McMillian to the crime. Plus, McMillian didn’t fit the profile of a murderer: He had no prior felony convictions, just one misdemeanor for getting dragged into a bar fight years earlier.

Still, the police were desperate to wrap up the Morrison case, and they felt that this was their opportunity. McMillian already had a target on his back from his affair with Karen Kelly, and the police had that target in their sights.

Walter McMillian’s Biased Trial

The Morrison case had generated considerable publicity in Monroe County, which was 40 percent black, and so Walter McMillian’s trial was moved down south to Baldwin County — which was 86 percent white.

Myers already pleaded guilty as an accomplice in Morrison’s murder and received a 30-year prison sentence — avoiding a possible death sentence for the Pittman murder. But McMillian always proclaimed his innocence.

His trial start on Aug. 15, 1988 and lasted only a day and a half.

The prosecution presented their three witnesses: Myers and the two men who said they saw McMillian’s “low-rider” truck outside the dry cleaners on the morning of the murder. No fingerprints, no fibers — not a single piece of physical evidence connecting McMillian to the crime scene.

Meanwhile, six witnesses testified in McMillian’s defense, saying he was hosting a fish fry at his house during the crime. One of his friends said they were working on that same truck that morning; the transmission was out of it.

But the jury — 11 white members and one black member — took the prosecution’s word. They convicted McMillian of first-degree murder.

The jury recommended a life in prison, but judge Robert E. Lee Key, Jr. overrode their recommendation and imposed the death penalty.

“It was too hard in light of the evidence of his innocence to show this court that he should never have been here in the first place.”

McMillian lost an appeal in 1991 and his conviction and death sentence were affirmed.

McMillian’s original attorneys in the trial, J.L. Chestnut and Bruce Boynton, later testified that the state withheld evidence that proved his innocence.

Bryan Stevenson Steps In

The upcoming film, Just Mercy, focuses on a petition for a new trial led by Walter McMillian’s lawyer, Bryan Stevenson of the Equal Justice Initiative.

“We in the African American community have always known that the criminal justice system is a threat, that it will take people who are innocent or wrongly convicted and it will treat people unfairly,” Stevenson said in an interview with Essence magazine. “But we keep fighting.”

Stevenson obtained the recording where Myers confessed to the Morrison murder, but when they flipped the tape they heard the same man complaining about confessing to a crime he and McMillian did not commit.

After an investigation revealed that McMillian’s truck was converted to a “low-rider” six months after the crime took place, the eye-witnesses recanted their testimony and admitted to lying.

Justice (Kind Of) Prevails

There was no evidence proving Walter McMillian’s guilt, and a mountain of evidence proving his innocence — and the police’s and prosecution’s racist complicity in his conviction.

On Feb. 23, 1993, the Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals reversed McMillian’s conviction and ordered a new trial. A week later, prosecutors dismissed the charges. For the first time in six years, Walter McMillian was a free man.

When asked whether his change of fortune restored his faith in the justice system, McMillian simply replied, “No. Not at all.”

Equal Justice Initiative With his conviction overturned, Walter McMillian was released from death row in 1993.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled against McMillian in a civil lawsuit filed against state and local officials in Alabama, citing that a county sheriff can’t be sued for money damages.

As a result, Alabama passed its 2001 compensation statute.

“I think everybody needs to understand what happened because what happened today could happen tomorrow if we don’t learn some lessons from this,” said Stevenson on the day McMillian’s charges were dismissed.

“It was too easy for one person to come into court and frame a man for a murder he didn’t commit. It was too easy for the state to convict someone for that crime and then have him sentenced to death. And it was too hard in light of the evidence of his innocence to show this court that he should never have been here in the first place.”

McMillian later developed dementia and died in 2013, but his name lives on at the center of the criminal justice reform movement.

After reading about the remarkable life and work of attorney Bryan Stevenson, who’s saved hundreds from prison, learn all about the case of the Central Park Five, a group of non-white teenagers who were wrongfully convicted of brutally raping a white woman in the 1980s. Then, read the harrowing last words of 23 executed criminals.