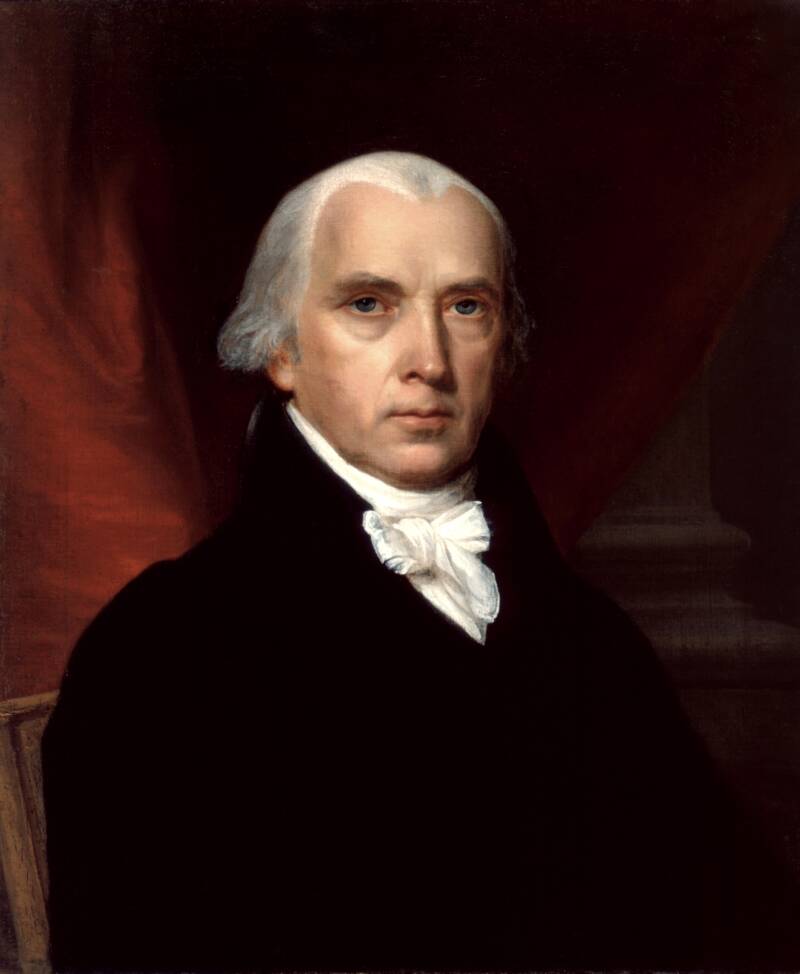

James Madison is widely credited with writing the first 10 amendments to the Constitution that comprise the Bill of Rights, but he didn't act alone.

Nearly every American has heard of the Bill of Rights, the document that contains the first 10 amendments to the U.S. Constitution. Ensuring rights like freedom of speech, religion, and assembly, this resource is clearly important. But who wrote the Bill of Rights — and why was it written in the first place?

No one was more proactive in getting the first 10 amendments in writing than James Madison, whose efforts resulted in these liberties being ratified as the Bill of Rights on December 15, 1791. But Madison didn’t act alone.

Interestingly enough, the Bill of Rights was initially shrugged off as unimportant by many politicians. But before long, the Constitution’s supporters realized that this bill was essential to preserving their new document.

Although the Constitution was originally created in 1787, it had only become the official framework of the American government a year later, when New Hampshire became the ninth state of 13 to ratify it.

Wikimedia CommonsScene at the Signing of the Constitution of the United States (1940). Illustrated by Howard Chandler Christy.

As a new country, the United States had only just established its power for the first time with the Declaration of Independence in 1776. In its wake, the Founding Fathers recognized the need for a foundational document to cement the inalienable rights we so appreciate today.

But the road to get there was not a smooth one.

What Is The United States Bill Of Rights And Why Is It Important?

Essentially, the Bill Of Rights is comprised of the first 10 amendments to the United States Constitution. As an individual document, it aimed to satisfy opponents of the Constitution, who felt it wasn’t explicit enough in curbing governmental power and ensuring individual liberties.

As such, the Bill of Rights was just as motivated by the desire to overcome opposition to the Constitution as it was by inscribing essential freedoms into law. At a time when the U.S. consisted of only 13 states, it was important to address those who were calling for further clarity.

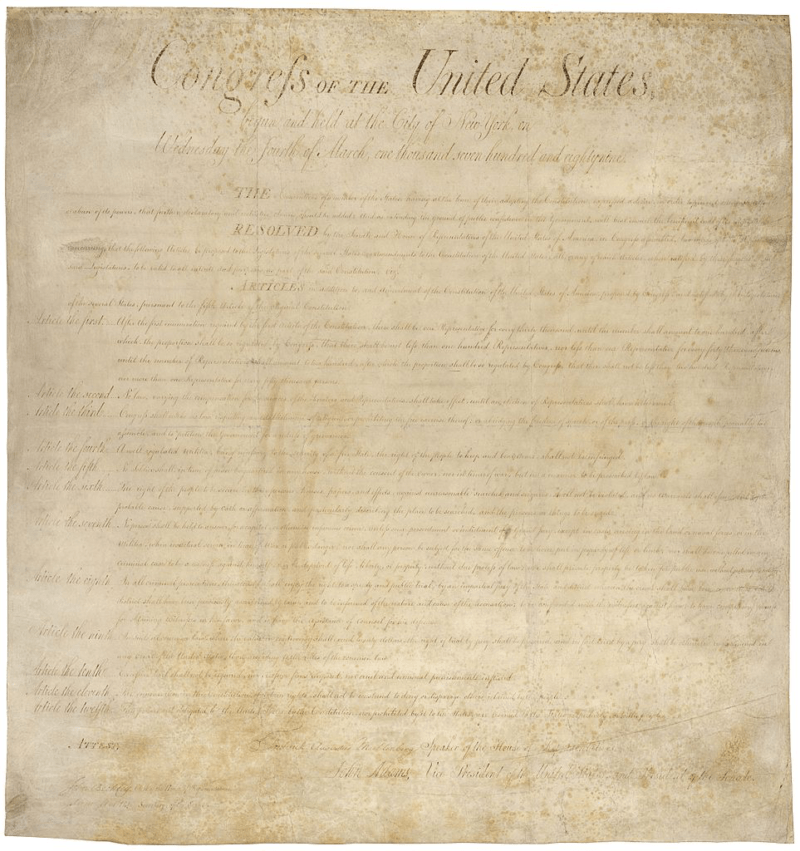

Wikimedia CommonsThe first page of the Bill of Rights.

Across states, arguably the most crucial people to please were the Anti-Federalists. People with this ideology believed that power should remain mostly in local governments, with its supporters thus calling for limits on federal power in the Constitution.

Meanwhile, Federalists, who supported a strong national government, were unbothered by the lack of clarity. As such, the Bill of Rights was arguably a compromise:

Amendment I

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.

Amendment II

A well-regulated militia being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed.

Amendment III

No soldier shall, in time of peace, be quartered in any house without the consent of the owner, nor in time of war, but in a manner to be prescribed by law.

Amendment IV

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no warrants shall issue but upon probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

Amendment V

No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a grand jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the militia, when in actual service in time of war or public danger; nor shall any person be subject for the same offense to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use without just compensation.

Amendment VI

In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the State and district wherein the crime shall have been committed, which district shall have been previously ascertained by law, and to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the assistance of counsel for his defense.

Amendment VII

In suits at common law, where the value in controversy shall exceed twenty dollars, the right of trial by jury shall be preserved, and no fact tried by a jury shall be otherwise reexamined in any court of the United States, than according to the rules of the common law.

Amendment VIII

Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.

Amendment IX

The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.

Amendment X

The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.

On the other hand, many of the sentiments behind the Bill of Rights dated back to the Magna Carta of 1215. Facing an uprising, King John of England was forced to negotiate with the British people when they took control of London. The subsequent 63-clause agreement imposed stringent limits on royal rule, including the right to a fair trial.

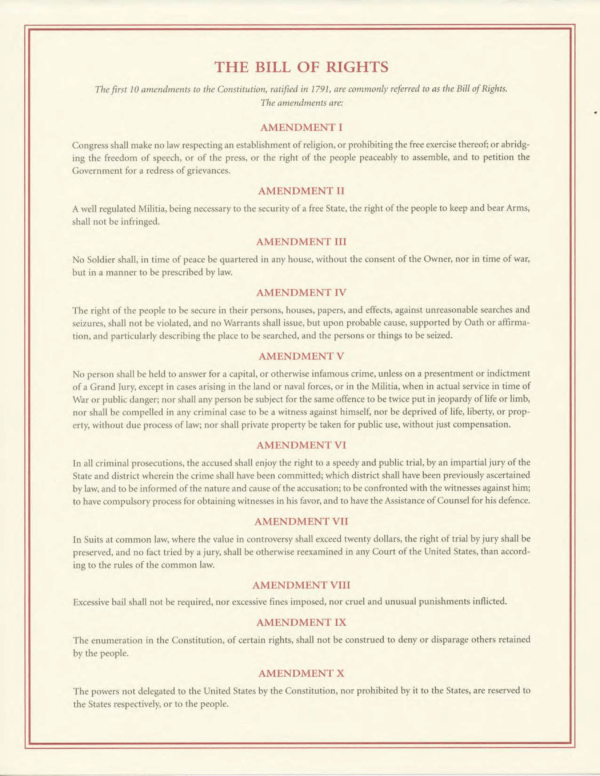

National ArchivesA printed version of the Bill of Rights, published during the George W. Bush administration.

Additionally, the English Bill of Rights of 1689 made numerous guarantees that were echoed by America’s, such as forbidding cruel and unusual punishment.

It’s no surprise that some American legislators were inspired to craft such limits into law. Most essential among them were George Mason, Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and of course James Madison.

Who Wrote The Bill Of Rights?

The Bill of Rights was in many ways the result of several states drafting their own. George Mason’s Declaration of Rights for Virginia quickly became the model for many that followed. The 1776 document was partly inspired by philosopher John Locke’s notion that people had natural rights that deserved protection.

As part of the committee that wrote Virginia’s declaration, Mason’s document stated that “men are by nature free and independent, and have certain inherent rights… namely the enjoyment of life and liberty.” Naturally, this heavily inspired Thomas Jefferson’s more famous declaration of 1776.

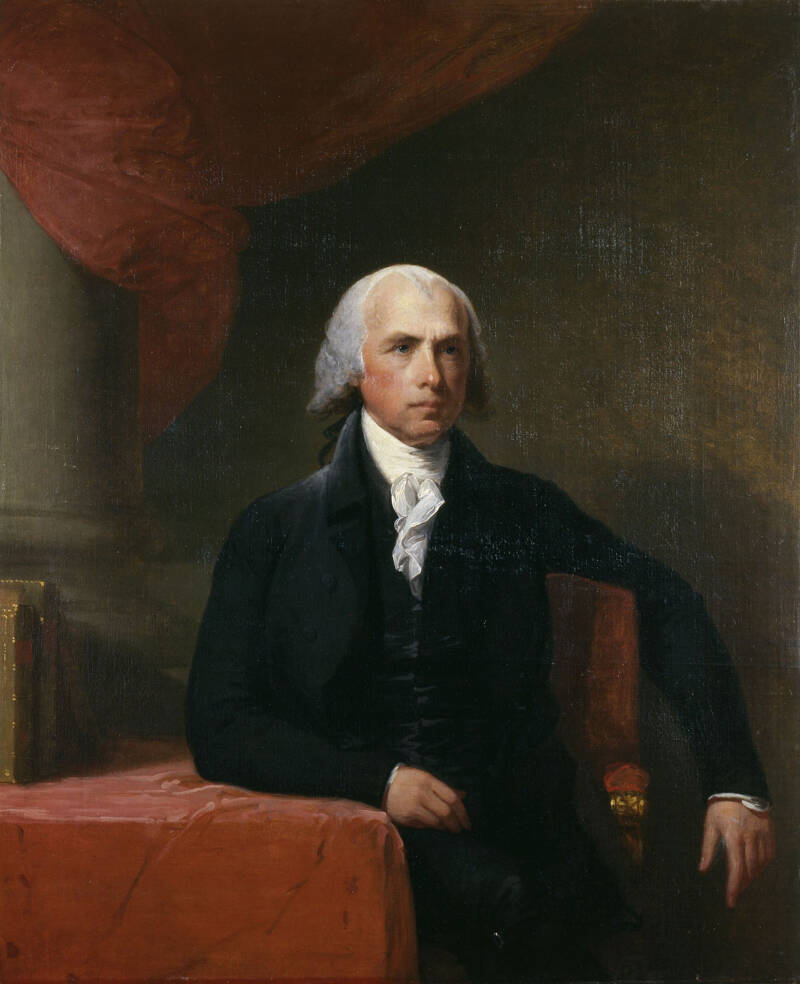

Wikimedia CommonsYears after drafting the Bill of Rights, James Madison became the fourth president of the United States.

Speaking up at the 1787 Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia, Mason said he “wished the plan [or Constitution] had been prefaced by a Bill of Rights.” While Elbridge Gerry moved to appoint a committee to craft one, the delegates swiftly defeated the motion, deeming it unnecessary.

Anti-Federalists used this opportunity to further denounce the Constitution, claiming that the absence of a bill of rights was one of their primary objections. At this point, it became clearer than ever for Federalists like Madison that such a document must be created as soon as possible.

He sifted through amendments proposed by several states — navigating the hostility by Anti-Federalists who hoped to cripple the Constitution’s support.

National ArchivesThe Constitutional Convention, as illustrated by Junius Brutus Stearns in 1856.

In September 1789, both House and Senate agreed to a conference report that examined the language Madison had drafted into the proposed amendments to the Constitution. While certainly a promising step, the fight for ratification was far from guaranteed.

Making The Bill Of Rights A Reality

John Adams was a huge proponent of a bill of rights. While away in Great Britain as the Constitution was being created, he read the document and stated the following:

“A Declaration of Rights I Wish to see with all my heart, though I am sensible of the Difficulty in framing one, in which all the States can agree.”

To his point, not even James Madison — arguably the most essential individual contributor to the Bill of Rights — believed in its importance. The future president agreed with the principles behind such a document, but claimed in 1788 that he “never thought [its] omission a material defect.”

Naturally, that all changed when it became clear that its omission could jeopardize the Constitution. After Madison presented his original 19 amendments to the House, the body agreed to 17 of them in 1789.

Wikimedia CommonsMadison was unconvinced a bill of rights was necessary — until Anti-Federalists claimed its absence motivated their hesitance to support the Constitution.

To Madison’s chagrin, the Senate decided to consolidate the list further by leaving an even dozen in the bill. After the states rejected two more, there were 10 left by the end of 1791.

Finally, on December 15, 1791, Virginia became the 10th of 14 states to approve the Bill of Rights — allowing it to pass into law.

Legacy And Contention

The impact of the Bill of Rights on America cannot be understated. While rather imperfect, as evidenced by the lack of an amendment abolishing slavery, it served as the foundation upon which such laws could be created.

Nonetheless, its wide-ranging interpretations have led to trouble. In a modern world where government institutions have enacted surveillance on American citizens and have detained them without due process, the bill’s enforcement remains controversial.

National ArchivesThe Bill of Rights on display at the National Archives in Washington, D.C.

But for the most part, the Bill of Rights has been admired by people all around the world. It remains imperfect — and it always was.

Perhaps, like the Constitution as a whole, it must be considered a living document that requires frequent reassessment in an ever-changing world that its authors couldn’t possibly foresee.

Of course, in the end, even this remains a hotly contested point — with a constant push and pull unlikely to ever completely end.

After learning the history of the United States Bill of Rights, explore colorized Civil War photos showing the war as it really was. Then, learn the most fascinating facts about every single U.S. President.