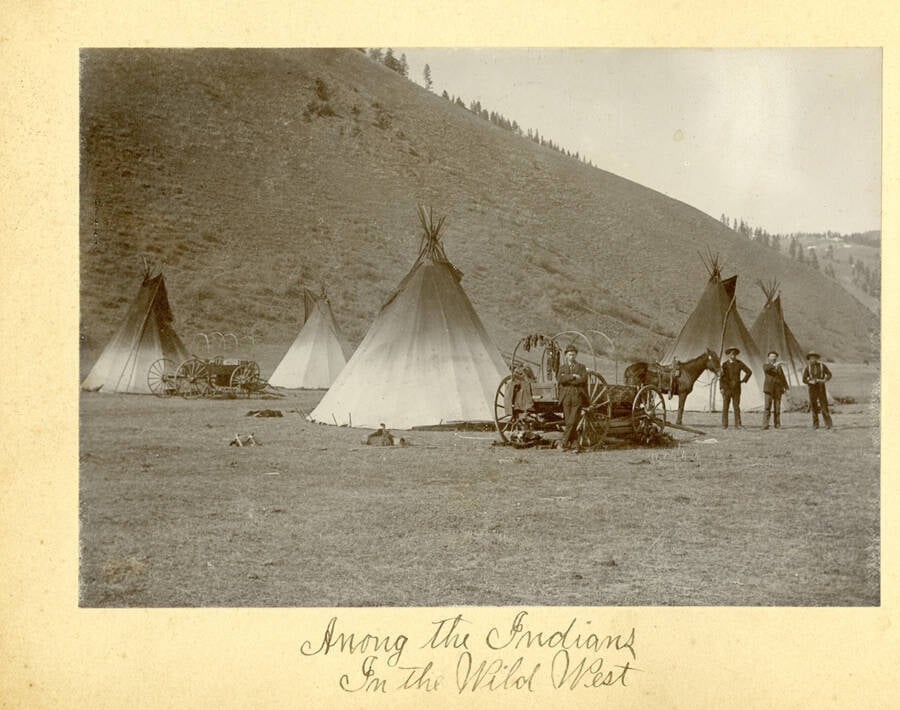

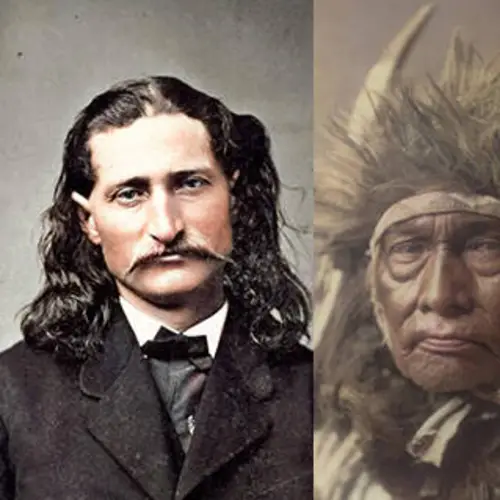

Between 1865 and 1900, tens of thousands of settlers moved to Montana to become gold and copper miners, cattle ranchers, and brothel owners — leading to conflict with the Native Americans who already lived there.

Between the 1860s and the early 1900s, the American frontier was known as the Wild West. Although the media often paints this period in broad strokes of romantic adventure and lawless chaos, the reality was far grittier — and few places represented this better than Wild West Montana.

The mountains and plains of Montana inspired ideas of individualism and self-reliance, but this transformative era had a steep price. Violence was rampant, countless Native Americans were displaced, and the environment was greatly exploited. Life for the average person was a relentless test of endurance. It demanded intense toil and resilience against unforgiving conditions.

And when the Wild West eventually came to an end, much of what remained, especially in Montana, amounted to little more than abandoned ghost towns. Gold, silver, and copper rushes had created a frenzy, one that bled the land dry and established a “boom-and-bust” cycle that defined Montana’s economy for decades. For many, the dream of potential riches turned out to be a nightmare.

Take a look back at the reality of Wild West Montana through the gallery below:

The Gold Rush Brings Prospectors To The Rocky Mountains

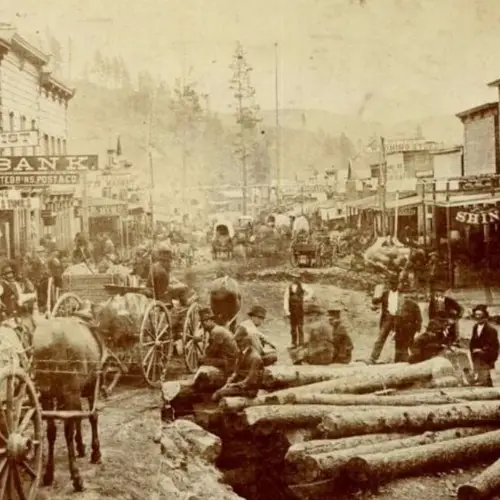

When gold was discovered near the Rocky Mountains in the mid-1800s, thousands of people flocked to Montana. Boomtowns like Bannack and Virginia City sprang up overnight as prospectors arrived with dreams of striking it rich. Local economies formed around this core idea, but the "boom-and-bust" nature of these settlements proved to be unsuitable for long term success.

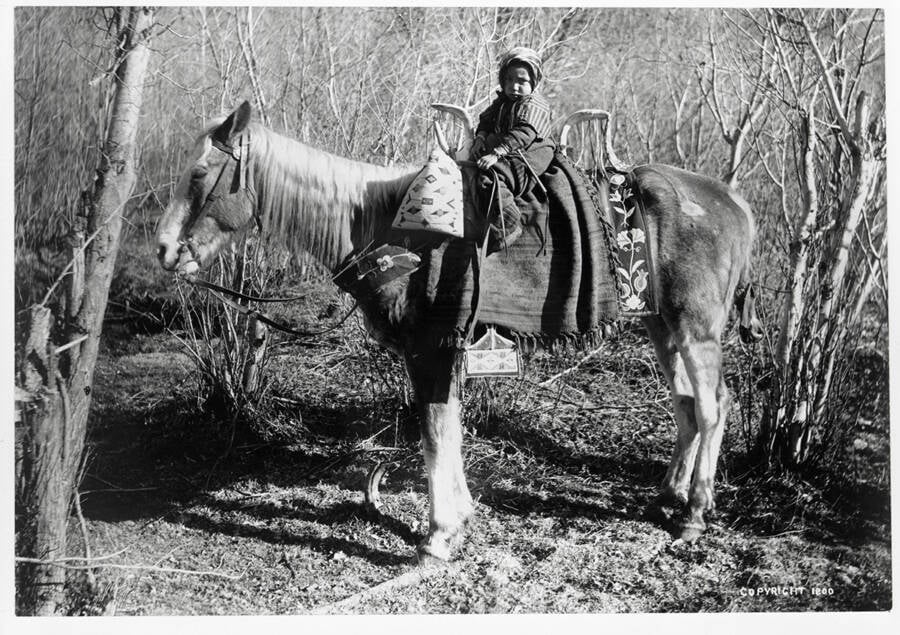

It certainly didn't help that these early, booming years were also built upon the dispossession of Native American lands and the destructive exploitation of the environment, which only intensified conflicts and brought disease to Indigenous tribes.

Montana State Library Digital CollectionsA Native American family by Lake McDonald in northwest Montana. Date unknown.

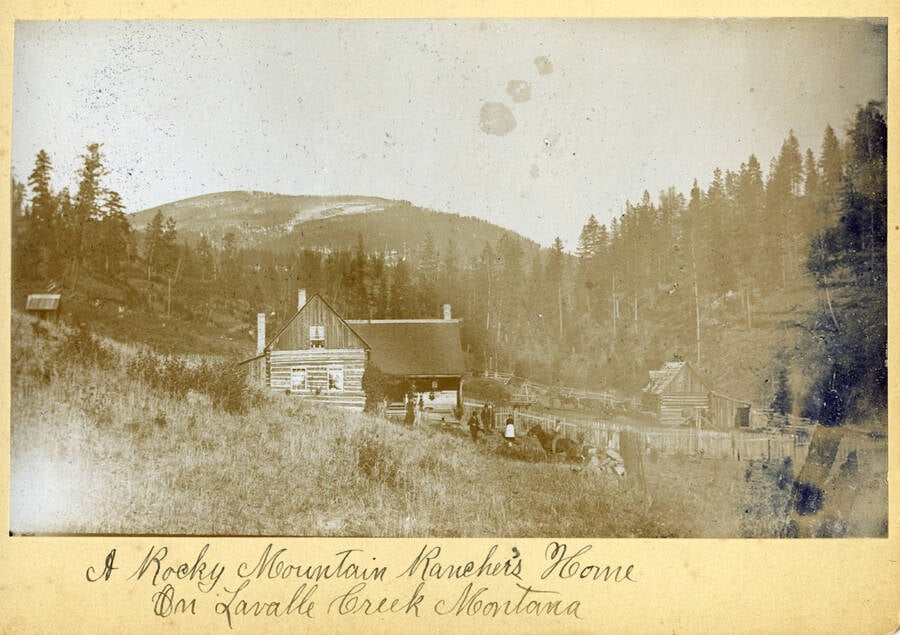

The fur trade was a lucrative business in the beginning, but as it faded, cattle and sheep ranching became facets of daily life. This was largely due to the vast open ranges of the plains — open ranges that were once inhabited by Native Americans and were now accessible because of policy decisions that gradually pushed Indigenous tribes onto smaller and smaller reservations.

Later legislation, such as the Homestead Act, fueled an even larger influx of agricultural settlers to these lands. Yet, as the Dust Bowl later proved, Montana's arid climate was difficult to tame for unaccustomed farmers.

Meanwhile, the burgeoning mining sector spurred growth in logging, farming, and other supporting industries. The arrival of railroads in the 1880s was a landmark moment, with companies now able to provide vital year-round transportation that helped towns like Billings and Butte grow. Eventually, these trains even brought some tourism, with travelers from the East Coast arriving to see the frontier and natural beauty of the Rocky Mountains.

For most people in Montana's Wild West, though, success was the exception, not the rule.

Daily Life In Wild West Montana

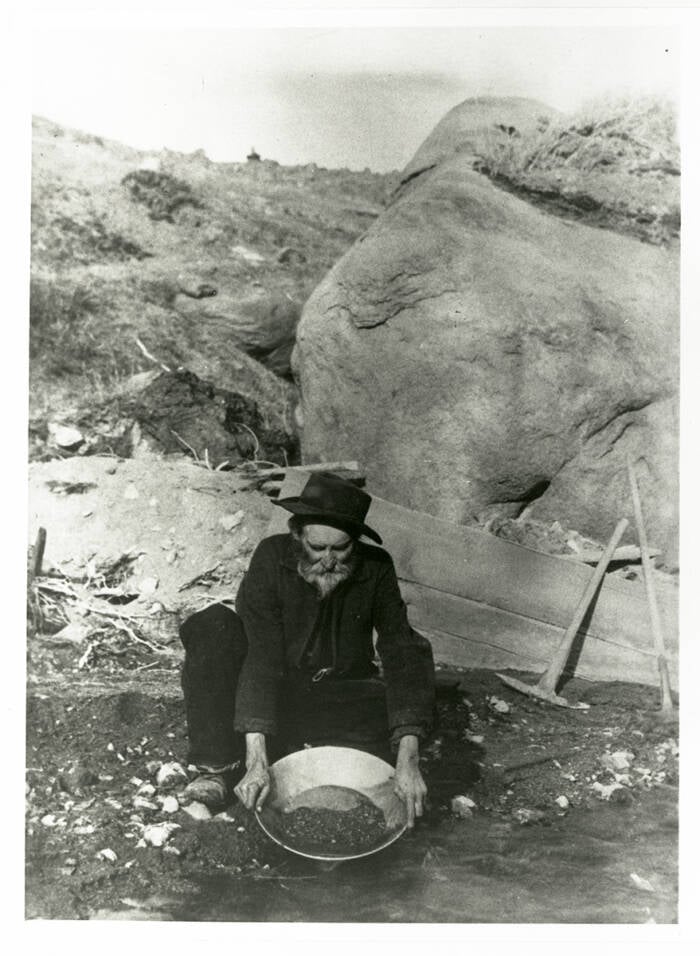

Life on the Montana frontier was, more than anything, an endurance test. Many had arrived in hopes of finding gold or other precious metals, but prospecting was no easy feat.

Most miners toiled long hours for scant returns, often spending all of their earnings on basic supplies — so that they could then mine for more gold. Their days were long and grueling as they fought against icy streams, frostbite, mosquitoes, flies, and any number of other potential health and safety risks. The camps they established were notoriously lawless and rife with robbery and claim disputes, and the mental toll was just as bad as the physical.

Montana State Library Digital CollectionsA prospector named Jerry Embrey panning for gold in Park City, Montana, between 1898 and 1910.

Things weren't much better elsewhere, either. Life on a homestead was a ceaseless, year-round battle for survival that involved every family member. Planting, chopping wood, making candles, hunting, and the endless preparation of food filled the days of farmers. Women, despite not receiving much credit at the time, were often the unsung heroes of this lifestyle, managing domestic tasks, serving as informal doctors, and generally keeping households afloat. Child labor was also widespread, and all the while, homesteaders faced sickness, malnutrition, and starvation.

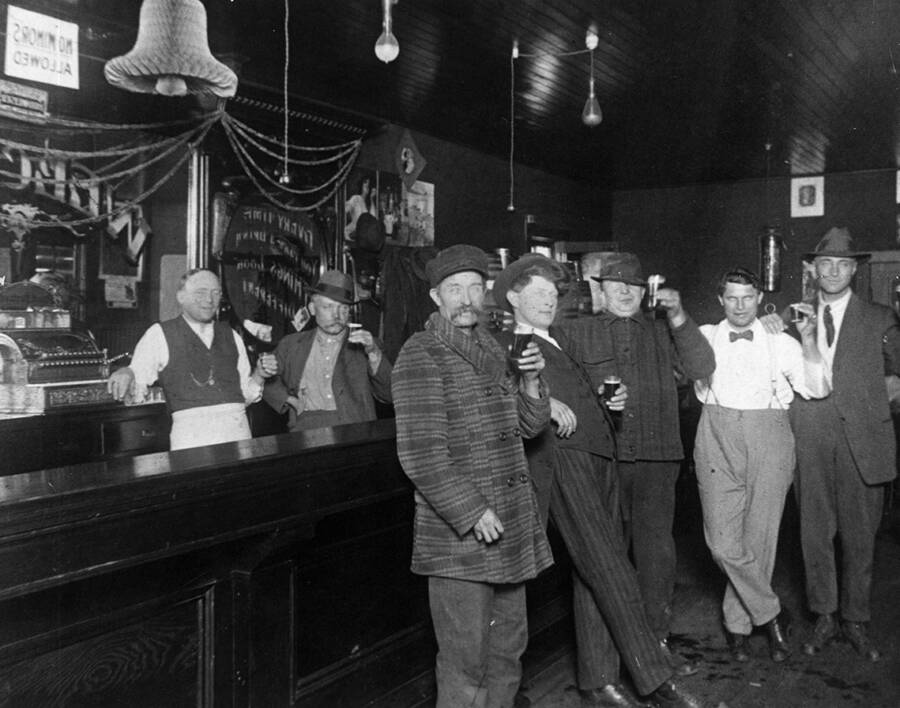

Towns were built quickly and abandoned regularly, but even when they thrived, they had to deal with poor sanitation, refuse-strewn streets, a general lack of hygiene, and frequent subjugation to the constant battles between outlaws and lawmen. And even if vigilantes and cowboys seemed to live freer, less constrained lives, that came at the cost of personal safety as they dealt with the harsh elements, dangerous animals, and, well, gunshots.

It should also be noted that throughout this period, Montana — along with much of the Wild West — was not even a state yet. That didn't happen until 1889, a year before the frontier was officially closed by the U.S. Census Bureau, marking the beginning of the end of the Old West era.

The Wild West Era Comes To An End

By the late 19th century, the time of the Wild West was coming to a close. In the winter of 1886 and 1887, the "Big Die-Up" marked a major turning point for the frontier, as extreme cold, deep snow, and sparse vegetation decimated the cattle that roamed the open range. Across the Plains, ranchers saw losses of 50 to 90 percent, according to OldWest.org, prompting a rapid shift away from free-roaming herds.

Montana State Library Digital CollectionsMen sharing a drink at Christmastime in an Old West saloon in Bonner, Montana. Late 19th or early 20th century.

Three years later, when the frontier was officially declared closed in 1890, there was no clear demarcation left between settled and unsettled land. That same year also saw the Wounded Knee Massacre, which conclusively ended organized Indigenous resistance on the Plains.

Montana's 1889 statehood, meanwhile, slowly but surely brought formal legal systems, railroads, and government authority, replacing the vigilante justice of the preceding decades. Towns like Bannack and Virginia City — once lawless boomtowns — became ghost towns and, later, tourist destinations. They preserved the frontier myth rather than being an active part of it.

Montana, like the rest of the American frontier, ultimately evolved into a regulated, settled society. The Wild West was over.

After reading about life in Wild West Montana, check out 33 photographs that show what life was really like in Wild West mining towns. Then, read all about the life of Calamity Jane, American history's most notorious frontierswoman.