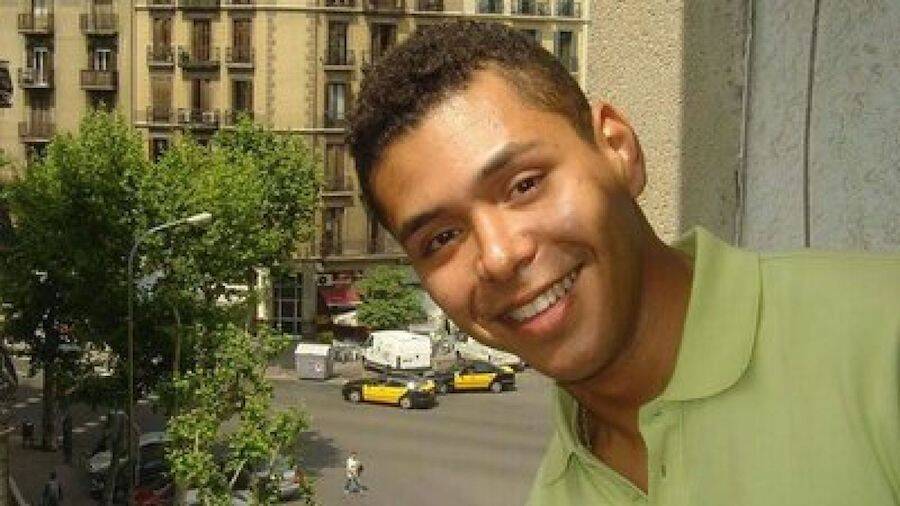

Adam Castillejo was tragically diagnosed with both HIV and Hodgkin's Lymphoma. In a miraculous twist, a stem cell treatment for the latter has cured him of the former.

FacebookThe 40-year-old Londoner decided to reveal his identity and serve as an inspirational figure for those similarly afflicted.

In 2011, Timothy Ray Brown was known to the world as the “Berlin patient,” the only person in history functionally cured of HIV/AIDS. Now, according to a new case report published in The Lancet HIV journal, Brown is no longer alone.

Adam Castillejo — or the “London patient,” as he was known in preliminary medical reports published last year — has been free of the virus for over 30 months, leading doctors to declare him functionally cured of the virus as well.

According to the BBC, Castillejo’s recovery appears to have come about in much of the same way it did for Brown. Both he and Brown were diagnosed with cancer and received bone marrow transplants as part of a stem cell treatment to fight their diseases.

It was after these transplants that the presence of the HIV-1 virus in Brown and Castillejo’s bodies began to disappear. When doctors investigated the remission further, they discovered a historic anomaly in the genes of the bone marrow donors.

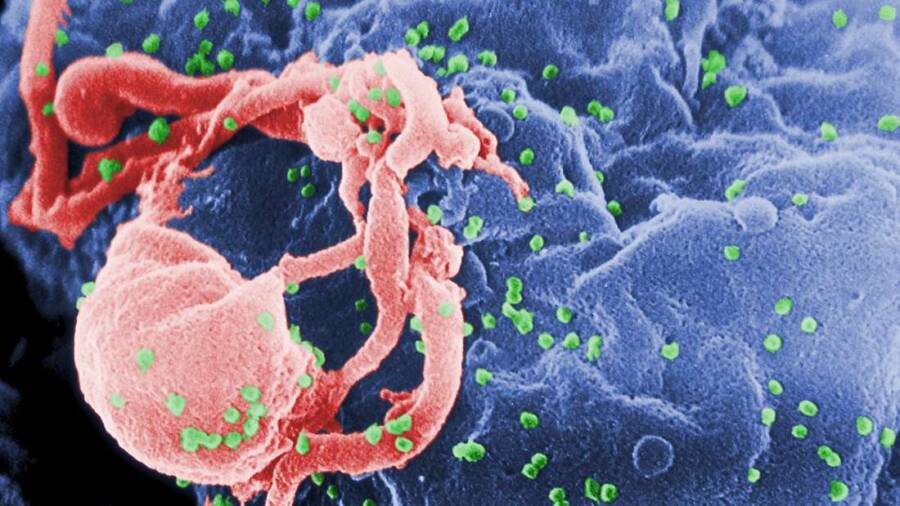

HIV-1 most commonly uses the body’s CCR5 receptors to break its way into cells, which it hijacks in order to create more copies of itself. A small percentage of humans are known to be HIV-resistant, however, and scientists believe that two mutated copies of the gene responsible for the CCR5 receptor might be why.

CDCThe HIV-1 virus strain commonly used the body’s CCR5 receptors to enter. Stem cell treatment could provide people with mutated CCR5 copies that prevent that from happening.

These versions of CCR5 effectively block HIV-1 from entering the cell through these receptors and, as a result, it cuts the virus off from its only means of reproduction. Harnessing these particular mutations of CCR5 receptor gene for potential treatments could be the key to the long-sought cure for HIV/AIDS.

“We propose that these results represent the second ever case of a patient to be cured of HIV,” said lead author and University of Cambridge professor Ravindra Kumar Gupta. “Our findings show that the success of stem cell transplantation as a cure for HIV, first reported nine years ago in the Berlin patient, can be replicated.”

In both cases, remnants of the HIV-1’s genetic material remain in the patients’ tissue, but the researchers explained that these are essentially harmless “fossils” of the infection — and are wholly incapable of reproducing the virus itself.

While Castillejo’s case first made news last year, doctors were hesitant to declare him cured, saying only that he was in nearly complete “remission of the virus.” Now, after more than 30 months in remission without antiretroviral therapy, they are ready to declare him free of the virus.

T.J. Kirkpatrick/Getty Images“Berlin patient” Timothy Ray Brown was the first person to be cured of HIV and has since become an advocate for funding and awareness. Castillejo, too, hopes to become “an ambassador of hope.”

Though the connection between bone marrow donors with the specific CCR5 mutations and the effective curing of the two men’s HIV infections appears strong, some are still skeptical that this factor is specifically responsible for ridding Castillejo of the virus.

“Given the large number of cells sampled here and the absence of any intact virus, is [Castillejo] truly cured?” Sharon R. Lewin, a University of Melbourne professor not involved in the study, said.

“The additional data provided in this follow-up case report is certainly encouraging but unfortunately, in the end, only time will tell.”

As for Castillejo, he recently decided to forego the traditional anonymity involved in HIV case reports and revealed his identity. The 40-year-old Londoner, who was born in Venezuela, explained that he wanted to help others come to terms with their diagnoses and forge ahead with optimism.

TwitterCastillejo has now been free of the virus for more than 30 months.

“This is a unique position to be in, a unique and very humbling position,” he said. “I want to be an ambassador of hope.”

While medical professionals have made incredible strides in blunting the lethality of HIV/AIDS, it remains fatal for many around the world. And even as modern HIV drugs have extended the lives of countless patients — allowing them to live as close to a “normal,” healthy life as possible — these drugs are still not a cure.

Unfortunately, Gupta says, this recent success is unlikely to translate to the global eradication of HIV — at least not right away. The stem cell transplants were only performed to treat Brown and Castillejo’s cancers, after all, and such a treatment can’t be undertaken lightly.

“It is important to note that this curative treatment is high-risk, and only used as a last resort for patients with HIV who also have life-threatening hematological malignancies,” he said. “Therefore, this is not a treatment that would be offered widely to patients with HIV who are on successful antiretroviral treatment.”

In the end, the fact that not just one, but two people have been cured of HIV is nonetheless encouraging and might just make this the most important — and positive — piece of science news in years.

After learning about the second person in history cured of their HIV infection following a stem cell treatment, take a look at 30 photos that changed the way we thought about AIDS. Then, learn about HIV’s scientific origins.