Animals suspected of wrongdoing were entitled to lawyers and fair and speedy trials, not to mention human-like executions such as hanging if they were found guilty.

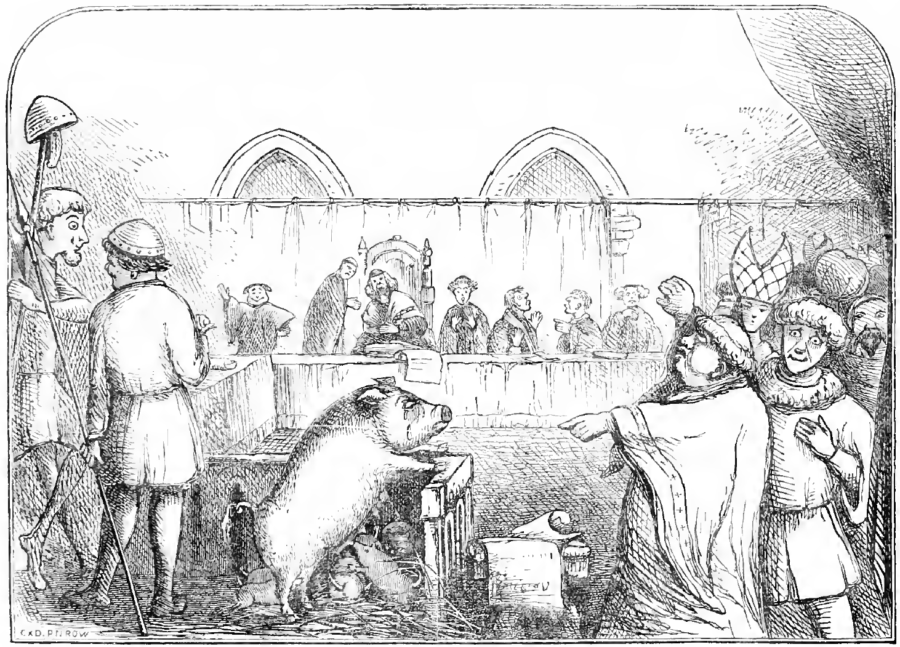

Wikimedia CommonsA sow and pigs on trial.

Rat infestations can be a pesky and all-too-common problem. However, the upside of the frequency with which humans have to deal with rats is that by now, everyone’s learned the only surefire way to get rid of them: Send them a polite, but stern, letter of warning.

Apparently, it worked quite well in medieval times.

When animals harmed humans, they would be subject to mutilation or execution, but not before being granted due process, including a full-blown trial.

In the Middle Ages, animals who committed crimes were subject to the same legal proceedings as humans. Edward P. Evans, a historian on the subject and author of a document called The Criminal Punishment and Capital Prosecution of Animals in 1906, wrote that rats were often “sent a friendly letter of advice in order to induce them to quit any house, in which their presence is deemed undesirable.”

See? Honest, healthy communication is all it takes, people.

Famously, in 1457, seven pigs in Savigny, France were tried for the murder of a five-year-old boy. The proceedings were complete with a defense attorney for the pigs and a judge, who ultimately ruled that because people witnessed one of the seven pigs attack the boy, only that one would sentenced to death by hanging, and the rest would go free.

Why the bother with animal trials back then? And why aren’t we at home on our couches watching squealing pigs being silenced by the domineering gavel and withering glare of Judge Judy?

Scholars and historians who study the middle ages have cited numerous possible explanations for why such proceedings took place. The greater mentality of medieval societies was characterized by strong superstitions and a rigid hierarchy of humanity rooted in faith a divine God.

Some academics hypothesized that, because of the importance of this belief system, any event that represented a departure in the hierarchy of nature, where a God had placed humans at the top, needed to be formally addressed in order to restore proper order. Another possible explanation for the trials was that because they were so public and conspicuous, they were able to serve as warnings directed at owners whose animals were causing mischief in communities.

Slate writer James E. McWilliams argues that, in the Middle Ages, unlike now, people treated animals more as sentient beings than as objects. Continued human interaction with the animals they owned, which amounted to up to 16 hours per day into the 19th century, left owners with more sympathy for them.

The late 19th century saw a shift in this outlook when agriculture yielded to industrialization, and as such animals are first and foremost viewed as capital-generating beings. He asserts that, consequently, putting animals on trial for crimes is not as outlandish as it might seem.

But moreover, had humans not stopped the practice of animal legal trials, think of how utterly captivating shows like The People’s Court and Law and Order would be today. Talk about the Golden Age of Television.

Next, read up on the Salem Witch Trials and the Hans Werewolf Trials.