Only living into her mid-20s, Ankhesenamun became the Queen of Egypt during the 18th Dynasty when she married King Tut.

Ankhesenamun was born Princess Ankhesenpaaten sometime around 1350 B.C., the third of six daughters born to King Akhenaten and Queen Nefertiti. For over three thousand years, much of her life has been a mystery, a fascinating patchwork of bizarre facts and strange omissions.

Though her story is remarkable in its own right, it’s Ankhesenamun’s half-brother who catapulted her to historical prominence: King Tutankhamun, or King Tut, is the most famous Egyptian pharaoh on the planet because of his intact, treasure-laden tomb found in 1922.

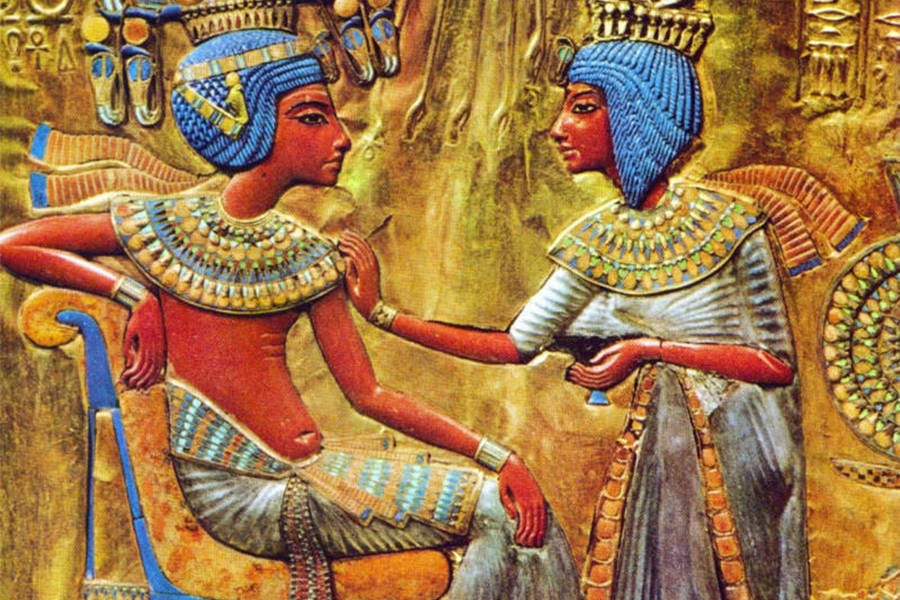

Wikimedia CommonsAnkhesenamun, King Tut’s wife, shown on the right giving flowers to her husband.

And Ankhesenamun was his wife. Yes, you read that right: Ankhesenamun was both King Tut’s half-sister and his wife.

It was a different world. Egypt was experiencing dramatic religious upheaval, and a dynasty hung in the balance. Incestuous marriages among the ruling class was common.

In fact, Ankhesenamun’s marriage to Tutankhamun might not have been her first inter-family marriage — or even her last.

The Religious Upheaval That Made A Dynasty Disappear

Wikimedia CommonsStatues of Akhenaten and his queen, Nefertiti, at the Neues Museum in Berlin.

Incest made sense to the ruling families of Ancient Egypt. Their power came with its own mythos; many believed — or at least publicly claimed — they were descended from gods.

Inter-family marriages, then, were about keeping a sacred bloodline pure. They also concentrated power in the royal family’s hands, effectively delegitimizing other contenders for the throne.

With no understanding of genetics, they were incapable of grasping the dangers of incest — and they paid the price. Though his parentage is uncertain, many point to Tutankhamun as a victim of inbreeding, citing evidence of a clubfoot and other serious congenital health issues in his remains. Some have argued his parents were likely full siblings.

It was a fate Ankhesenamun was destined to share.

Historians have discovered compelling evidence that the mysterious royal lady might, as a third daughter of the pharaoh, have served as a bride for her father, Akhenaten, after Queen Nefertiti died — but before she was married to her brother Tutankhamun.

Wikimedia Commons A depiction of Akhenaten and his family.

She wasn’t alone; historians believe that Akhenaten may have tried to conceive children with Ankhesenamun’s older sisters. The stories on the walls of family tombs suggest those pregnancies ended in miscarriage and death.

Akhenaten — and his dynasty in general — were in a particularly vulnerable position, which is perhaps one reason he felt securing a wide field of heirs was important.

Their difficulties were entirely of his making. Akhenaten was in the process of overhauling centuries of Egyptian religious tradition in a stunning and unprecedented move toward monotheism.

Flickr / Richard MortelAkhenaten, Nefertiti, and their daughters are displayed under the rising image of Aten, the sun disc.

Though history tells us what he did, few records remain to help us understand why Akhenaten turned his back on the old gods and embraced Aten, the sun-disc, as the supreme being for Egyptians to worship.

It was a decision that had the potential to undermine the entire Egyptian power structure, and it was particularly dangerous because it dismantled the authority of the priests, who were a powerful faction in their own right. Without their support, the royal family found itself increasingly friendless.

Ankhesenamun Marries Tutankhamun And The Old Gods Are Restored

Wikimedia Commons Ankhesenamun on the right, King Tut on the left, this time in shiny gold and full color.

The move away from Amun-Ra and the rest of the Egyptian pantheon, gradual at first, had a dramatic effect on the Egyptian state.

With the priests disenfranchised, control passed to the army and the central government; bureaucracy reigned and bred corruption.

And then, just as suddenly as it had begun, the greatest religious revolution in centuries came to an end: Akhenaten died and Tutankhamun came to power.

Precariously placed and with little time to consolidate power, a young Tutankhamun wed his teenage sister, Ankhesenamun, and together they quickly retreated from their father’s radical religion.

Pressured, perhaps, by the priests who were a vital pillar of royal power, they changed their own names. Tutankhaten, meaning “the living image of Aten,” changed the suffix in his name to “Amun,” swapping his father’s sun-disc for the traditional sun god of the Egyptian pantheon.

Ankhesenamun, formerly Ankhesenpaaten, followed suit.

Just like that, the great transformation Akhenaten had begun — raising Aten, building new temples with the bones of the old, striking out Amun-Ra’s name and prohibiting worship of the old pantheon — was over.

But peace still proved elusive.

The Brief And Unstable Reign Of Tutankhamun and Ankhesenamun, Egypt’s Royal Teenagers

Wikimedia CommonsA depiction of King Tut with a cane on the walls of his tomb.

It was a frightening time; both the king and queen were very young and in charge of running the entire country. Tut and his bride initially relied on powerful advisors to govern the ancient nation — a policy that may have eventually proved their undoing.

Tut’s time as king wasn’t the happiest. His mummy suggests he was frail and plagued by illness — a hypothesis corroborated by the discovery of hundreds of ornate canes in his famous tomb.

Heirs might have stabilized Tut’s reign, and evidence supports the idea that he and Ankhesenamun tried without success to have children. The mummies of two female fetuses, five to eight months in age, were found in King Tut’s tomb.

Genetic testing — possible because of the royal embalmers’ skill — confirms the unborn daughters belong to Tut and a nearby mummy, most likely Ankhesenamun.

It also reveals that the older of Tut’s unborn daughters, if brought to term, would have suffered from Sprengel’s deformity, spina bifida, and scoliosis. Once again, the royal family of Egypt suffered at the hands of genetic disorders they couldn’t understand.

Tut’s reign, though famous, was brief. He died young, at 19, in what historians for many years imagined to be a dramatic accident.

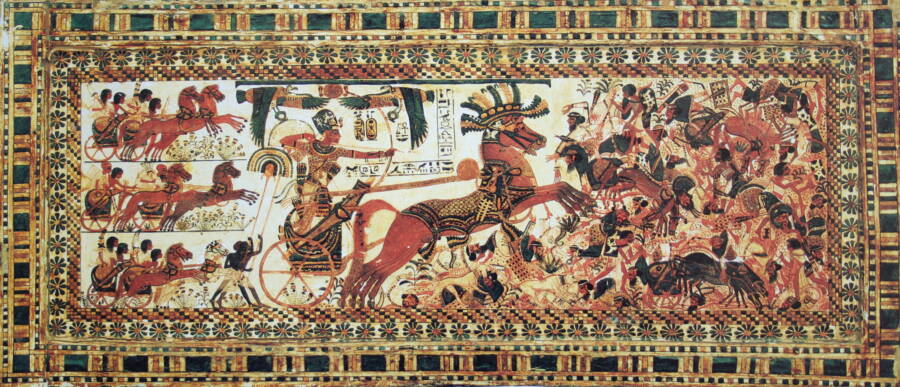

Inspired by the pictures of a healthy young man riding a chariot across the sides of Tut’s casket and around his tomb, some historians hypothesized a chariot race gone wrong, which would have explained the fracture in his leg and damage to his pelvis. Infection, they imagined, set in and led to death by blood poisoning.

Wikimedia CommonsA depiction of King Tut riding on a war chariot.

Others, noticing bone fragments in the royal mummy’s skull, postulated a blow to the head — perhaps murder by a scheming advisor or relative.

Further analysis, however, rendered this unlikely; Tut’s skull was intact, and the bone had actually chipped off a vertebrae in his neck — damaged that probably occurred some 3,000 years after his death when Howard Carter’s 1922 team pried off his gold death mask.

The latest thinking on Tut’s death blames an infection that resulted from a fracture in his left thigh — not the result of a chariot accident, since the king, with a number of physical impairments, probably could not have raced. His immune system, weakened from several bouts of malaria, couldn’t fight the infection.

Regardless of how it happened, the result was the same: Ankhesenamun was left to fend for herself.

What Happened To Ankhesenamun After Tut Died?

Wikimedia Commons Howard Carter opening King Tut’s sarcophagus in 1922.

King Tut’s wife may have next married Ay, a powerful advisor who was close to both her and Tut — perhaps because he was also her grandfather. But the historical record is unclear.

There is good reason to believe that life after Tut’s death was difficult and frightening for Ankhesenamun.

She may have been the author of an undated letter to Suppiluliumas I, the king of the Hittites. In the letter, an unidentified royal woman makes a desperate plea for the Hittite leader to send her a new husband; her old husband is dead, she says, and she has no children.

The letter’s author needed someone to be king of Egypt, and it didn’t matter if that someone came from Egypt’s chief military rival as long as he stepped in to save her kingdom.

Suppiluliumas I agreed to send Zannanza, a Hittite prince. But Egyptian forces, perhaps loyal to Ay, killed Zannanza at the border of Egypt. Rescue never came.

Wikimedia CommonsA statue of Ankhesenamun and King Tut at Luxor.

Ankhesenamun disappears from the historical record sometime between 1325 and 1321 B.C. — an absence that to historians signals her death. Because no one knows what happened to her, scholars have sometimes referred to King Tut’s wife as Egypt’s Lost Princess.

But it isn’t only time that has fragmented her story. Ankhesenamun’s role in one of Ancient Egypt’s most contentious periods was lost deliberately, excised from the annals of history by the new dynasty that rose to power just decades later.

Backed by the priests, the new rulers branded the sun-disc worshiper Akhenaten a heretic and scrubbed him and his immediate descendants from the list of pharaohs, sealing their tombs and consigning their stories to 3,000 years of silence.

After learning about Ankhesenamun, King Tut’s wife and sister, check out these shocking cases of famous incest throughout history. Then, read about Charles II of Spain, who was so ugly he scared off two wives.