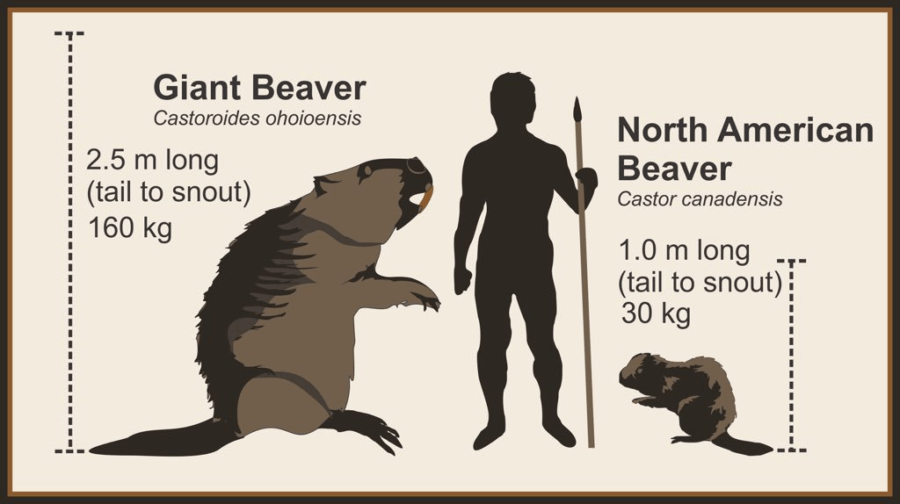

Both the giant beaver known as Castoroides and the average-size North American beaver co-existed during the Ice Age, but only one species survived.

Western UniversityAn illustration of the Castoroides giant beaver.

Some 10,000 years ago, a giant beaver known as Castoroides ohioensis roamed the Earth alongside woolly mammoths and other ancient megafauna. But this giant species became extinct with the end of the Ice Age while its smaller cousin was able to live on to this day. And now scientists know why: This giant beaver simply didn’t chuck wood like its smaller counterpart.

This giant beavers weighed about 220 pounds and could grow as long as eight feet — that’s about the size of an adult black bear. And Castoroides also came with huge incisors that measured six inches. One can only imagine what kind of damage those teeth could inflict on any wood within reach.

But according to a new study published in Scientific Reports, these extra-large mammals did not have the same habits or diets as modern-day beavers do, meaning that Castoroides did not use its giant incisors to cut down trees and wood to make dams.

“We did not find any evidence that the giant beaver cut down trees or ate trees for food,” said study co-author Tessa Plint, a former graduate student at Canada’s Western University who is now at Heriot-Watt University in the U.K. “Giant beavers were not ‘ecosystem-engineers’ the way that the North American beaver is.”

James St. John/FlickrA Castoroides skeleton.

Instead, the study found that this giant beaver sustained itself on a diet of aquatic plants. The combination of its consumption of marine-based plants and its inability to construct makeshift shelters made these animals extremely dependent on the conditions of their surrounding wetland environment.

But in order to determine the giant beaver’s diet, Plint and co-author Fred Longstaffe analyzed isotopes retrieved from the animal’s fossilized bones and teeth.

“Basically, the isotopic signature of the food you eat becomes incorporated into your tissues,” Plint said. “Because the isotopic ratios remain stable even after the death of the organism, we can look at the isotopic signature of fossil material and extract information about what that animal was eating, even if that animal lived tens of thousands of years ago.”

The effort was a collaboration with Grant Zazula from the Yukon Palaeontology Program, who has also worked as a science advisor for Hollywood productions set in the Ice Age.

TwitterA size comparison between a Castoroides giant beaver, a modern beaver, and a human.

Compared to the Castoroides, the North American beaver (Castor canadensis) is a fraction of its size. The modern beaver weighs a mere 66 pounds on average and grow up to 35 inches, excluding its tail. These two beavers also differ in terms of habits as the North American beaver is an herbivore and uses its large front teeth to gnaw through bark and build lodges for its home. Sometimes, they’ll even eat the wood that they work with.

Interestingly enough, these two disparately-sized beavers actually co-existed for tens of thousands of years in North America during the Pleistocene epoch, when the last Ice Age occurred.

After the Ice Age passed, the planet’s ice sheets retreated and the air became much drier and warmer. This meant that the wetlands inhabited by Castoroides were increasingly disappearing. Without the ability to adopt a new diet or adjust to a new kind of habitat, the giant beaver began to disappear along with the wetlands.

Meanwhile, the smaller North American beaver species remained relatively unaffected by the shifts in the environment.

“The ability to build dams and lodges may have actually given beavers a competitive advantage over giant beavers because it could alter the landscape to create suitable wetland habitat where required. Giant beavers couldn’t do this,” said Longstaffe, Western University’s Research Chair in Stable Isotope Science who co-wrote the study with Plint.

“When you look at the fossil record from the last million years, you repeatedly see regional giant beaver populations disappear with the onset of more arid climatic conditions.”

Western UniversityGiant beavers had six-inch front teeth but according to scientists, these incisors were not very efficient.

Dozens of other megafauna species went extinct during this time along with the giant beaver. Indeed, a species’ survival is not only about which animals are the strongest or biggest, rather it is about which creatures have the ability to adapt to the planet’s ever-changing environment.

Based on previous excavation of giant beaver bones and teeth, these creatures lived all over the continent before they went extinct, likely spending much of their time in the water areas of Florida, Alaska, and the Yukon Territory.

Although there is more left to uncover about these mammoth creatures that used to walk the Earth, Plint said that the findings from the study provide a “small piece of the puzzle” — and an intriguing one at that.

After this look at Castoroides the giant beaver, read about the giant prehistoric armadillo known as glyptodon. Then, read about the 50-foot prehistoric snake called Titanoboa.