The glyptodon may seem like just a big armadillo, but it was the size of a car and could crush early humans with its clubbed tail.

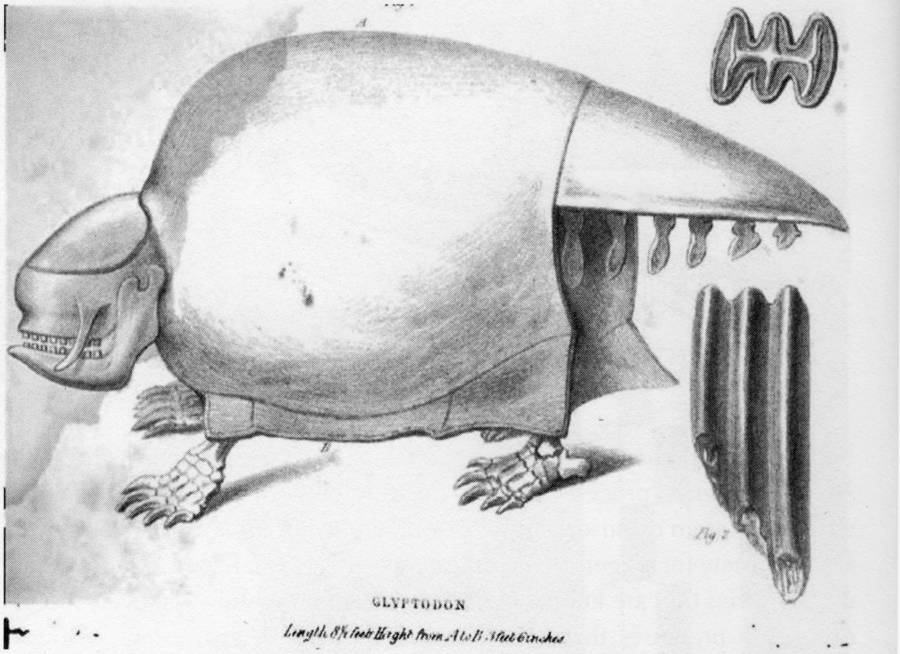

Wikimedia CommonsAn artist’s rendering of a glyptodon.

In prehistoric times, it seems as though every single animal was bigger than its modern counterpart. Mammoths were taller, hairier, and heavier than elephants. Ancient sloths grew to the size of modern-day elephants. Alligators and crocodiles routinely grew to the length of a city bus. And snakes were so big that they could eat alligators.

One such enormous prehistoric creature that dwarfs its modern counterpart — and a creature that our ancestors came in contact with — was the glyptodon, a giant armadillo about the size of a Volkswagen Beetle.

The Discovery Of Glyptodon

Wikimedia CommonsRichard Owen’s 1839 sketch of a glyptodon skeleton and the grooved teeth (right) that gave it its name.

Glyptodon reappeared on the scene in 1823, when an Uruguayan naturalist was shocked to unearth what turned out to be an eight-inch-thick, seven-pound femur unlike anything he had seen before.

The discovery of more large bone fragments in the area led experts to hypothesize that they belonged to an enormous ground sloth, but when a strange collection of bony plates turned up, a new theory was put forward: at some point in history, a giant armadillo had walked the earth.

Everyone had a different idea about what the new discovery should be called — and with all the different names being batted around in the scientific literature, many didn’t realize they were all talking about the same creature.

It took English biologist Richard Owen to point out what was happening, and since he resolved the confusion, it was his name that stuck: glyptodon, meaning “grooved tooth.”

When Glyptodon Walked The Earth

Wikimedia Commons A fossilized glyptodon.

Like an armadillo, glyptodon had a head and tail that protruded from a large shell. It also had an armored back made up of more than 1,000 bony plates that fit together tightly, which made the glyptodon’s back look more like a turtle’s than a modern armadillo’s. But unlike either of those creatures, glyptodon specimens regularly grew to 10 feet in length and weighed one ton.

Glyptodons lived from approximately 5.3 million to 11,700 years ago, which means that early humans coexisted with these large creatures. But our ancestors had little to fear because these herbivores weren’t hunters; they ate primarily plants as they roamed across present-day North and South America.

Wikimedia CommonsA glyptodon skeleton and shell.

Just as humans adapted to a wide range of climates and ecosystems on Earth, glyptodons did the same thing.

Some thrived in tropical areas, while other adapted to life on grassland prairies. A few managed to make their home in cold climates. But most fossils of these creatures come from a swath of South America that extends from the Amazon River basin to the vast plains of Argentina.

Wikimedia CommonsA spiky glyptodon tail.

Its size and hard backplates weren’t the only features that made this creature stand out. Its tail had a bony club on it, sometimes with spikes, that the creature could wield with deadly results. If you got too close to a glyptodon protecting its young, a quick whip of the tail could crush your skull instantly.

In fact, their tails were so strong that they could shatter the bony back plates of other glyptodons.

The picture that begins to emerge will sound familiar to dinosaur fans, who will recognize many of the distinctive features of ankylosaur: a big lumbering body, a bony mantle, and a deadly club tail.

The similarities aren’t a coincidence, but neither do they point to any link between these giant mammals and the famous Ornithischian dinosaur. What’s actually at work here is convergent evolution, a mechanism by which unrelated species evolve similar structures because they’re useful in a particular environment.

In short, similar problems — like being a large, slow-moving grazer with the need to defend itself during interspecies combat — resulted in similar evolutionary solutions.

And what formidable solutions they were. Humans and other animals weren’t quick to mess with these creatures — at least not without a plan.

Hunting And Subsequent Extinction

Wikimedia CommonsA depiction of prehistoric humans hunting a giant glyptodon.

Though no match for the glyptodon’s strength and size, humans were able to outsmart these animals and sometimes hunt them.

Although their backs and tails were strong and sturdy, their underbellies were soft. If a hunting group could turn a glyptodon over onto its back, they could throw sharp spears at the animal’s underside to kill it. That is, if they avoided the spiked tail and if they prevented the creature from curling into the world’s largest medicine ball.

But if humans could succeed in making a kill, the meat of such a large creature would have been a valuable resource. And not just the meat — fossil evidence found in South America has led some paleontologists to conclude that early humans used the empty shells as shelters from rain, snow, and inclement weather.

Yes, these creatures were so large that the shells of the dead could serve as makeshift shelters for early humans. Imagine our ancestors huddling under a giant armadillo shell during intense tropical rainstorms or fierce blizzards.

Ultimately, however, hunting is what likely led to the glyptodon’s downfall. Scientists believe that the last glyptodons died out shortly after the last Ice Age because of overhunting by humans as well as climate change.

But their remarkable shells remain preserved in the fossil record, and they sometimes turn up in the unlikeliest places — a reminder of the strange and wonderful creatures of a lost world.

After learning about giant prehistoric armadillos, read up on the terrifyingly large prehistoric snake known as Titanoboa. Then, discover some other fearsome prehistoric creatures — that weren’t dinosaurs.