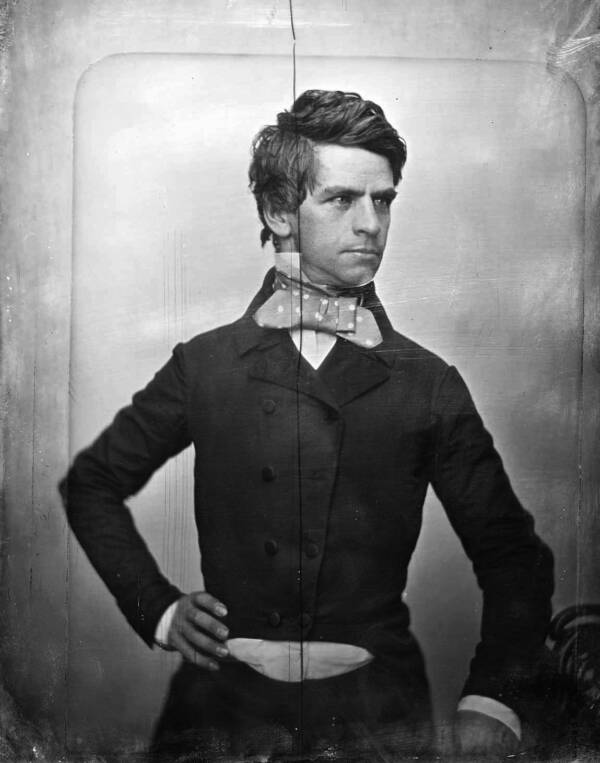

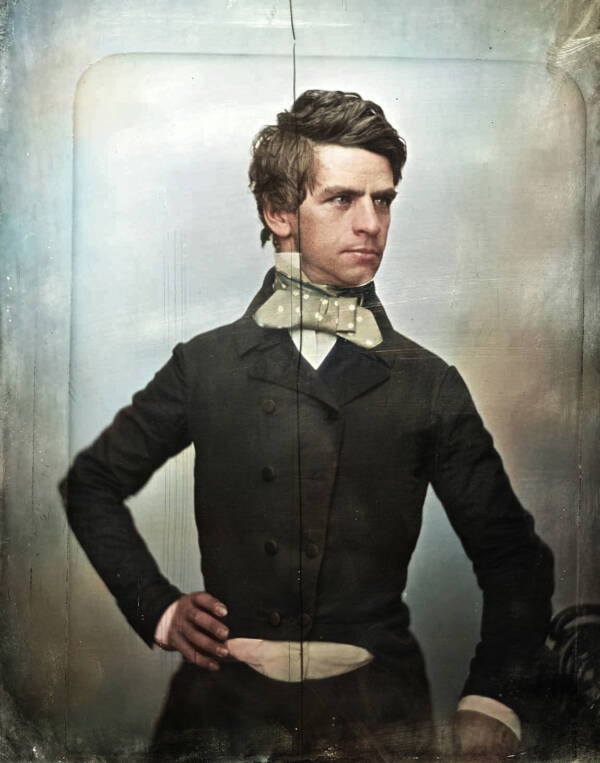

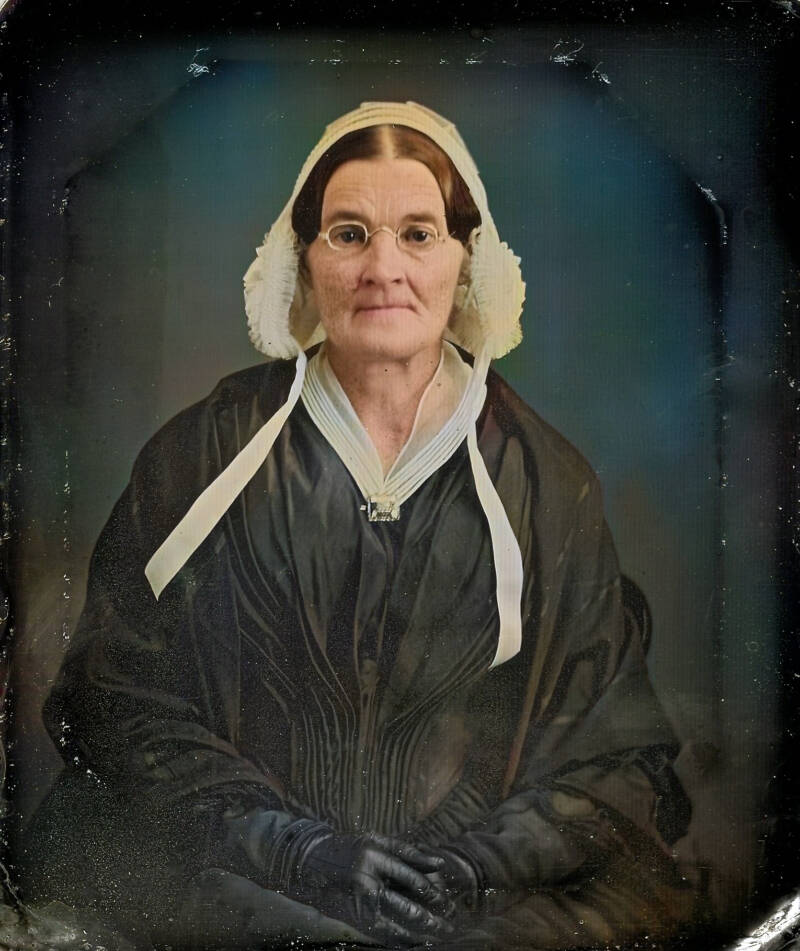

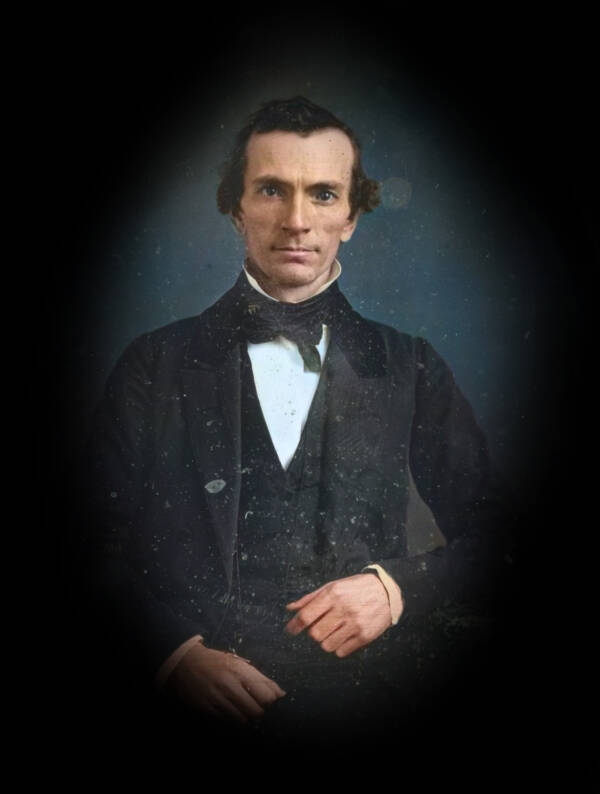

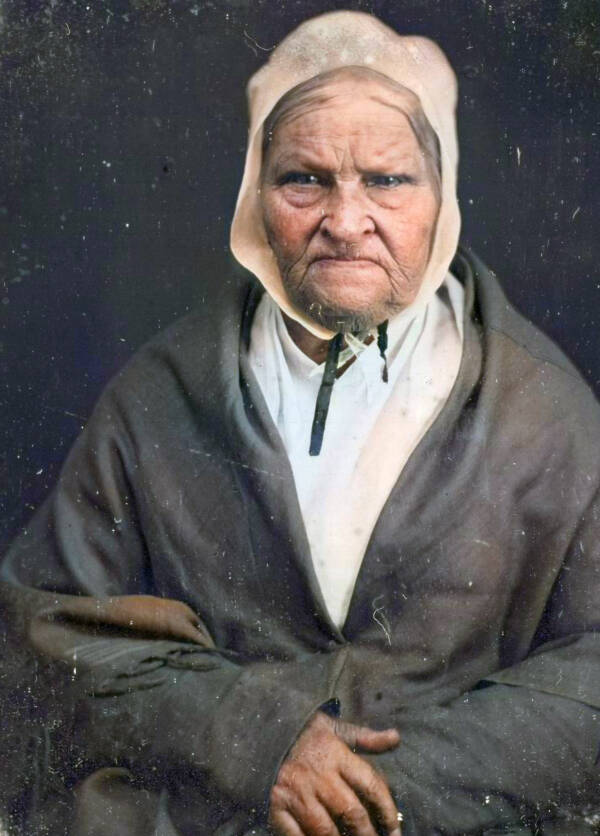

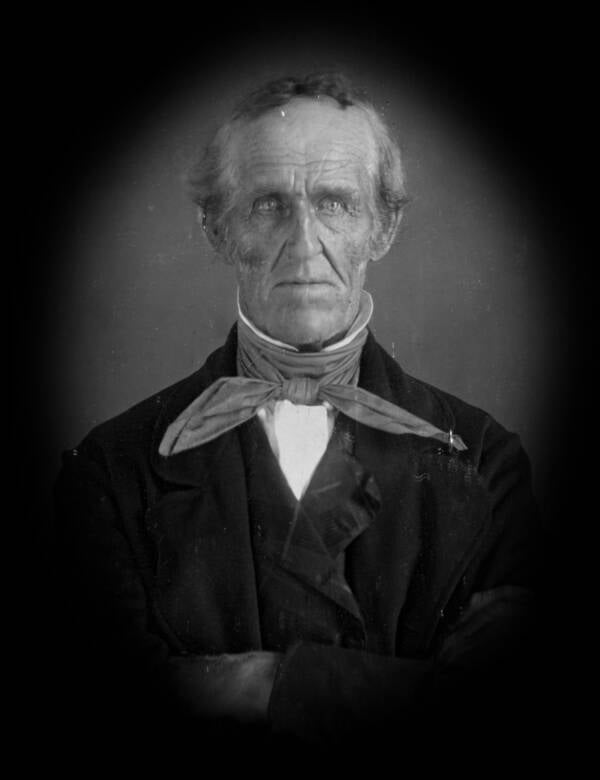

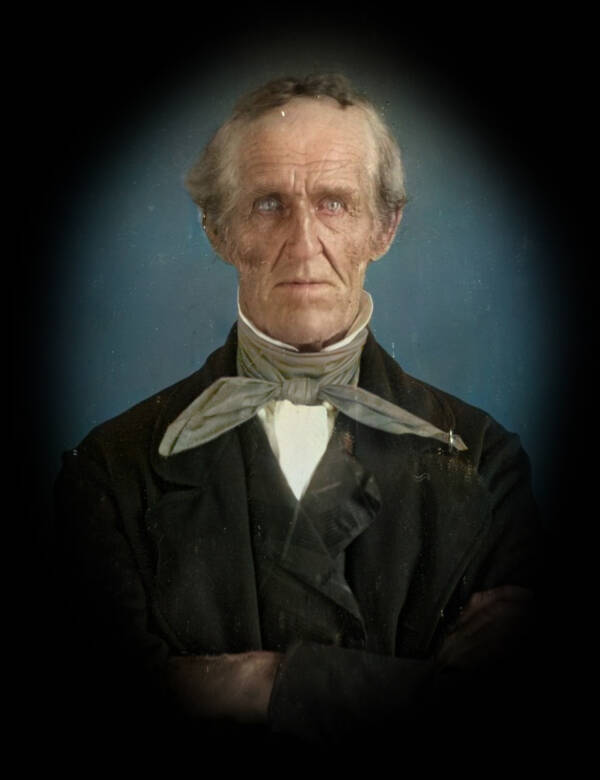

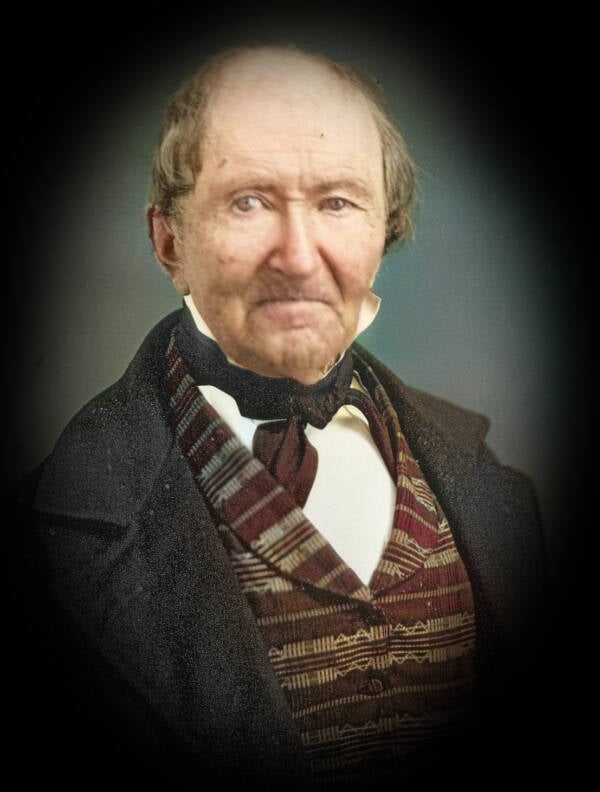

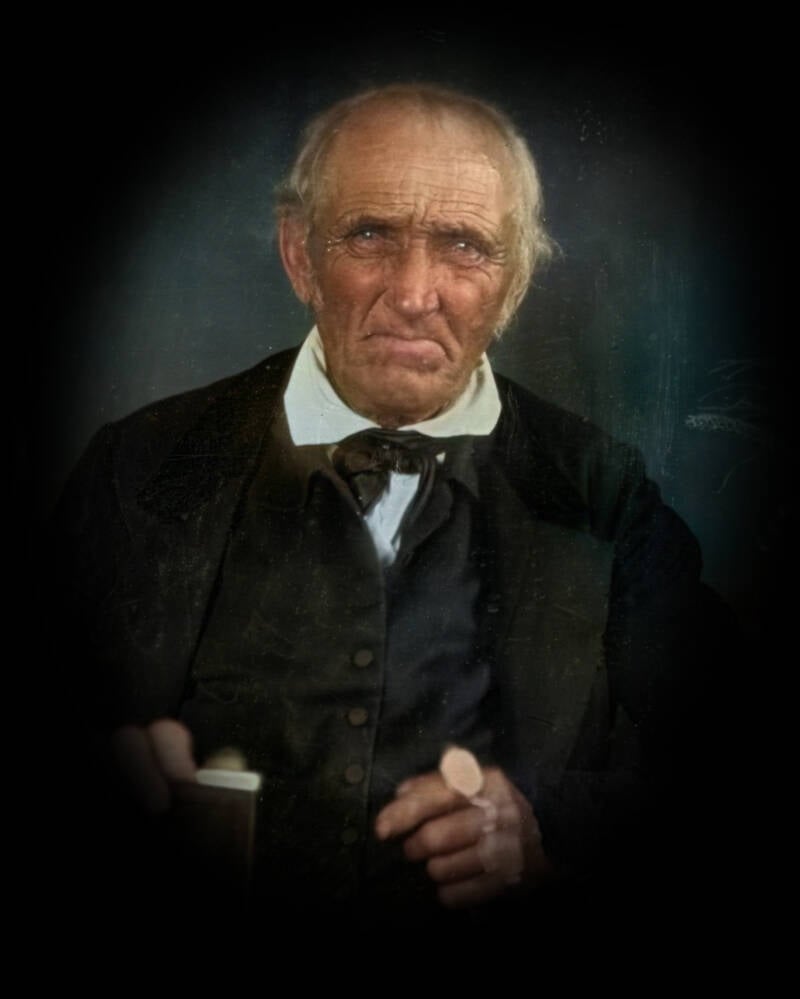

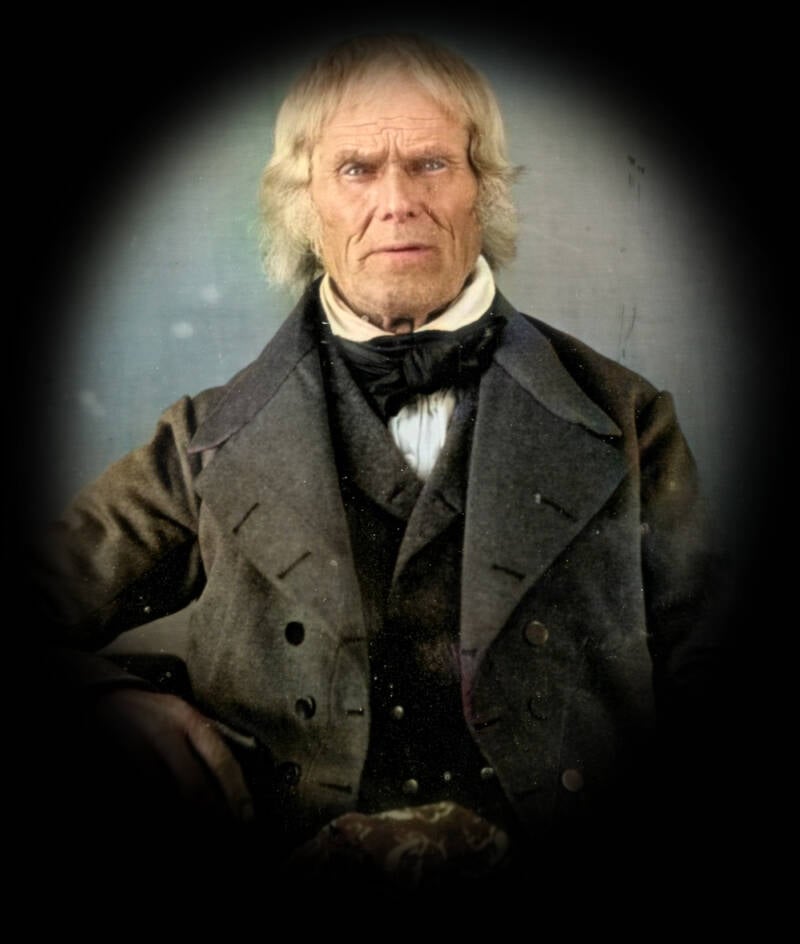

These daguerreotypes from the 1840s and '50s — newly restored in vivid color — capture a generation of Americans that lived through the Revolutionary War and the execution of Marie Antoinette.

The first photograph ever taken — a blur of gray shapes captured in 1826 or 1827 — doesn't resemble the photography we know today. In fact, modern photography wouldn't come into focus until around the 1840s.

Wikimedia CommonsAn enhanced version of the first photograph ever taken made in 1952 by Helmut Gersheim.

It likely took the creator of the first photograph, Nicéphore Niépce, at least a few hours and perhaps several days of exposure to capture his image. Taken from a window in Burgundy, France, the image was immortalized on a pewter plate coated in bitumen that was diluted in lavender oil.

The process was called "heliography," but the method took on a more efficient form in 1838 when Niépce's partner, Louis Daguerre, took the oldest known photograph of a person.

The product, naturally dubbed a "daguerreotype," was presented to the French Academy of Sciences in 1839.

The daguerreotype quickly became the most popular form of photography. As the method was refined and advanced, it only required people to sit still for about a minute to capture their portrait, thought sometimes children would be bound and restrained in order to keep them from moving while their image was being captured.

The process was nonetheless rather involved compared to today's standards of photography. First, a sheet of silver-plated metal had to be polished and made reflective. That sheet was treated with fumes that rendered it light-sensitive, transferred to a camera using a light-proof box, and finally, it was exposed to light.

An image would then be left on the surface of the metal — a direct-positive image, not a negative like in modern film photography — which would be treated with hot mercury and fixed with a salt solution. The result was a remarkably detailed image in black, white, and gray.

The method was used to capture landscapes and and portraits, as moving images would turn out blurry. The daguerreotype became the foundation for the printing process throughout the latter half of the 19th century, and remained immensely popular even after Kodak released the first commercially available celluloid film in 1889.

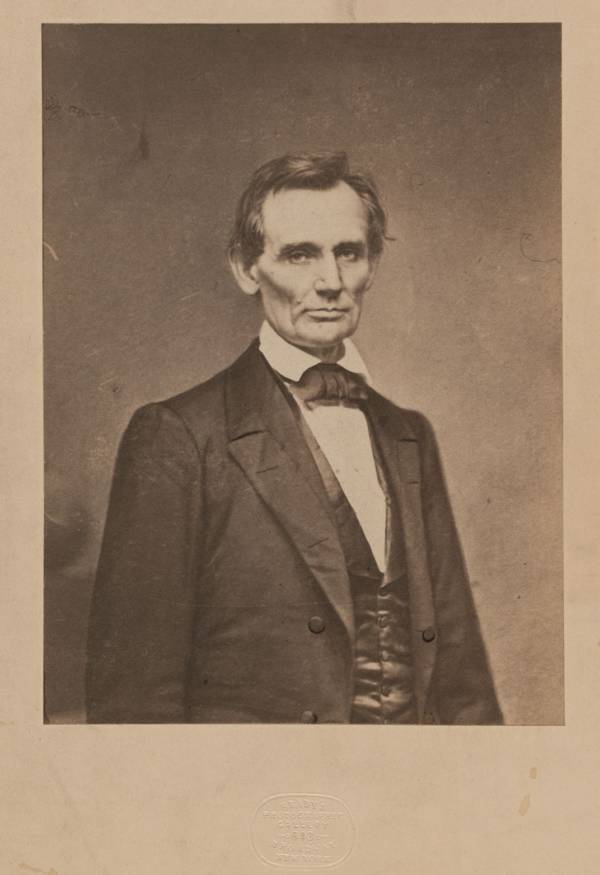

The photographs in the gallery above are all daguerreotypes from the 1840s and '50s, when the method was most popular. Daguerreotypes were also used by one of the earliest photographers in American history, Mathew Brady, known for his startling images of the American Civil War.

Mathew B. Brady / National Portrait GalleryThis photograph of Abraham Lincoln, taken on Feb. 27, 1860, was done by Brady who was known to photograph the likes of Union officials Ulysses S. Grant, George Custer, and George Stoneman.

Because photography in the 19th century was so involved, the art form was mostly reserved for professionals. It also wasn't cheap to get a portrait. In 1842, a daguerreotype could go for anywhere from $81 to $195 by today's standards. Thus, many of the people in the gallery above were likely of considerable means.

But perhaps most notable about these portraits is that they are of arguably the oldest generation of people ever to be immortalized on film. Some of the older faces in the gallery could have been born in the late 1700s, rendering these portraits the first visual record of themselves that they had; it was the first time they could look at their own faces without looking into a mirror.

The colorization process has been rendered significantly more efficient since digitization. Matt Loughrey, who colorized these portraits, uses a computer program that recognizes the relationship between greyscale hues and their corresponding colors. He corresponds with libraries and museums for original and high-quality scans of photographs; high-quality scans with clear resolution are integral to rendering an accurate colorization.

Among his favorite periods to colorize is the American Civil War because it's "a very storyful era," he says. Indeed, on the faces of those pictured above are the stories of two wars on American soil, the agita of everyday life before the turn of the century, and the recognizable glimpse of excitement for having one's photo taken for the first time.

Next up, check out these fantastic colorized photos of New York City from 100 years ago. Then, explore the mugshots of 33 of the most recognizable criminals — in vivid color.