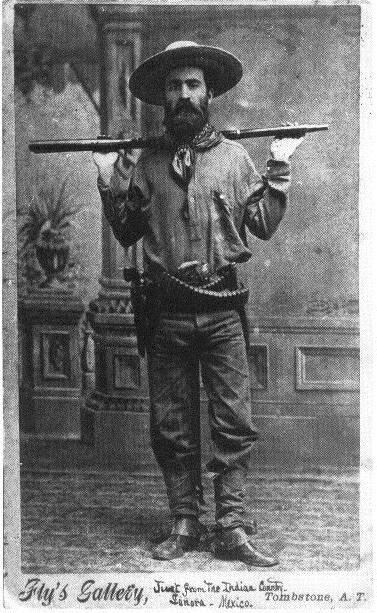

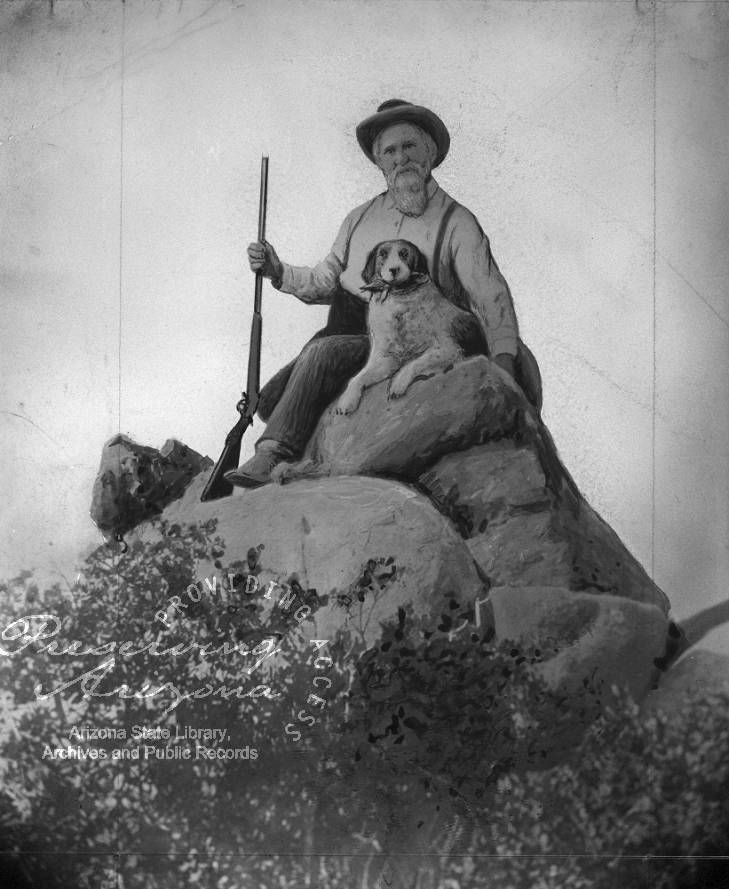

Based in Tombstone, Arizona, C.S. Fly documented the peace treaty between Apache Chief Geronimo and the U.S. Army in 1886, as well as other iconic moments of the Old West.

Even if you don't recognize his name, you will likely recognize his photographs.

As one of the premier photojournalists of his time, C.S. Fly is in part responsible for preserving the image of the Wild West as we know it today through his iconic photography.

Fly gained access to some of the most iconic names of the 19th century: Apache Chief Geronimo and the bandits behind the shootout at the O.K. Corral.

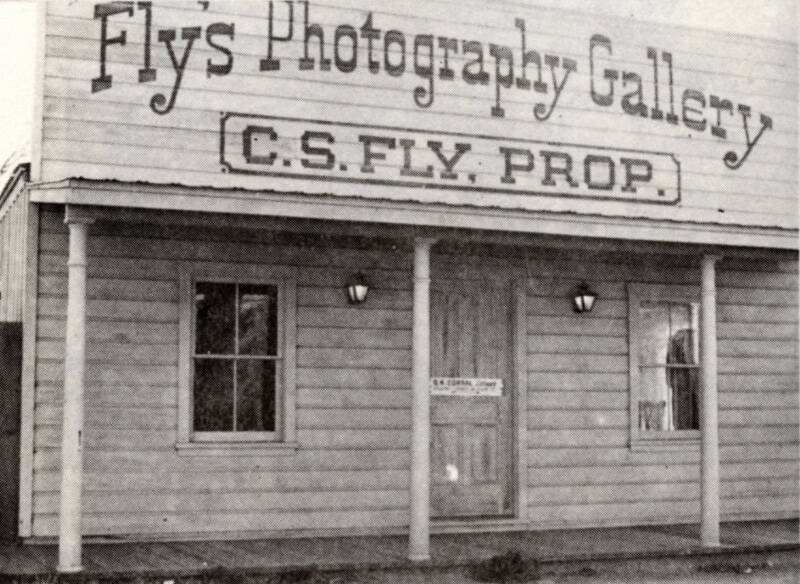

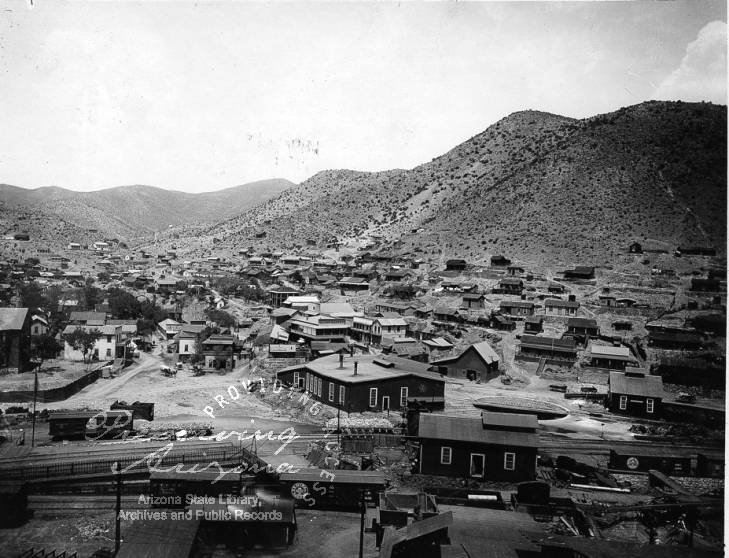

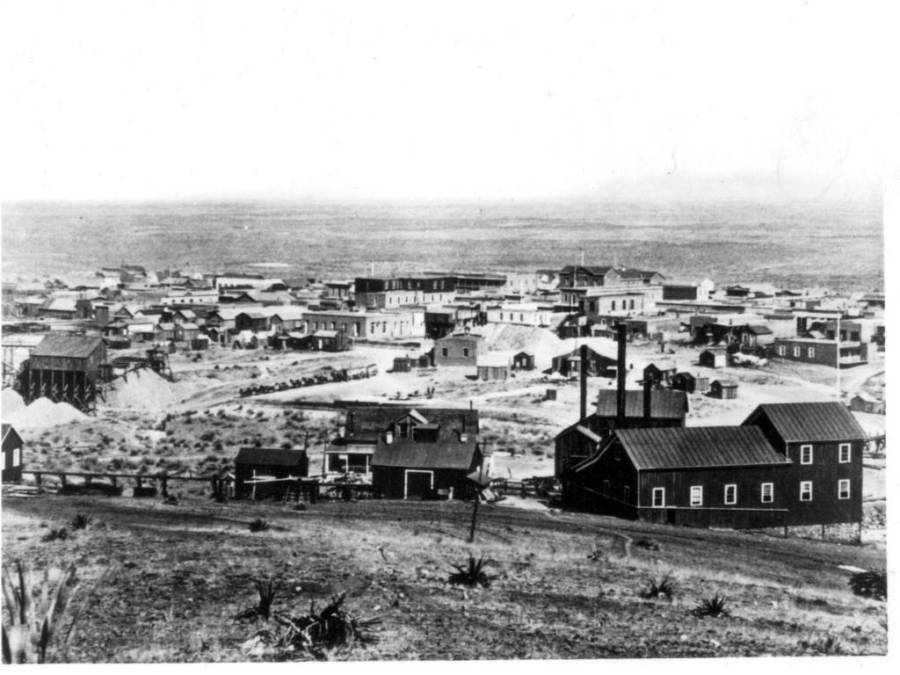

Without his studio in the notorious boomtown of Tombstone, Arizona, we would be sorely lacking some dimension to our ideas of the frontier.

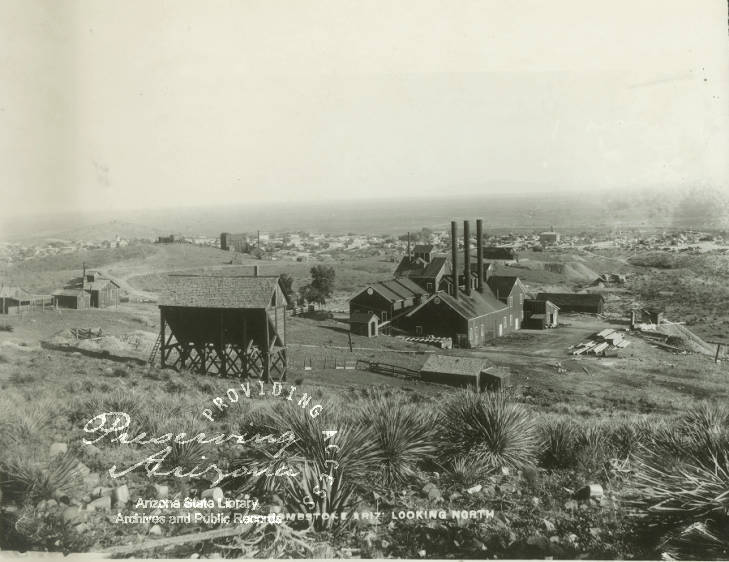

C.S. Fly Goes To Tombstone, Arizona

C.S. Fly/Wikimedia CommonsC.S. Fly and his wife Mollie moved to Tombstone, Arizona in 1879. This is a photograph he took of the small Western town in 1881.

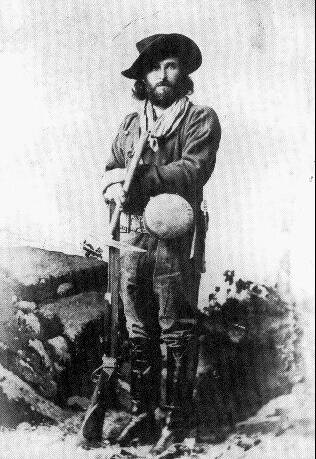

Camillus Sidney Fly was born the seventh child of Captain Boon and Mary Percival Fly in Andrew County, Missouri in 1849. He often went by the nickname "Buck."

Immediately after his birth, "Buck's" parents packed him and his six siblings up and made the trek to Napa County, California, where Buck Fly would grow up. It was here that he discovered his passion for photography.

After marrying fellow photographer Mary "Mollie" Goodrich in 1879, Fly made his way to that emblematic town of the Wild West, Tombstone, Arizona.

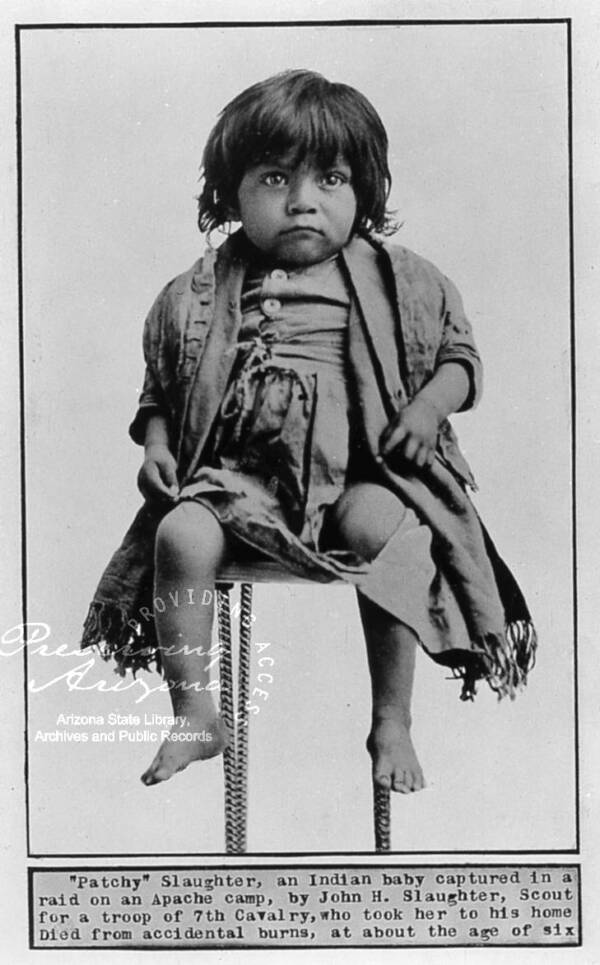

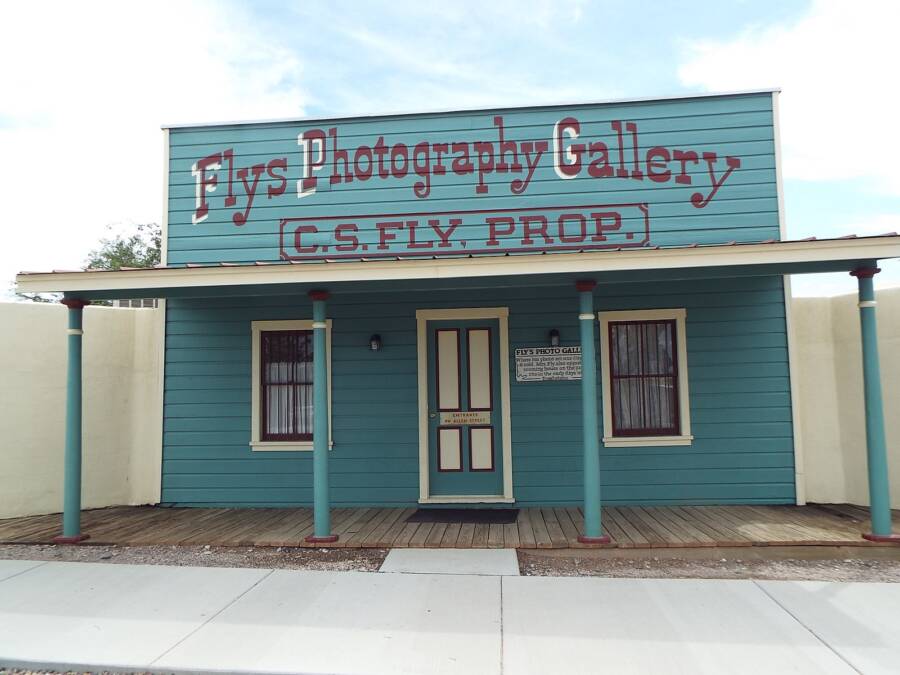

In the booming silver-mining town of Tombstone, Mr. and Mrs. Fly set up their first studio. The couple initially did their business out of a tent, but then opened the now-famous "Fly's Photography Gallery" on Fremont Street. They also manned a 12-room boarding house and adopted an orphan girl named Kitty.

At the studio, people could pay 35 cents for a professional cabinet photograph taken by either Buck or Mollie. This is about eight dollars by today's standards.

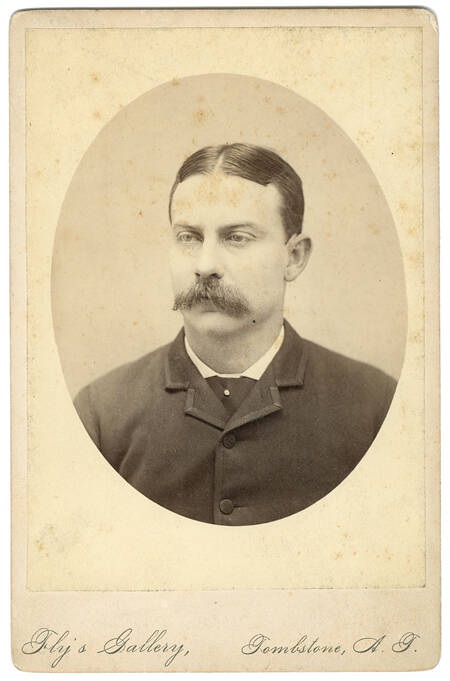

The Journal of Arizona HistoryDuring their later separation, Mary "Mollie" Fly stayed in Tombstone and took over Fly's Photography Gallery.

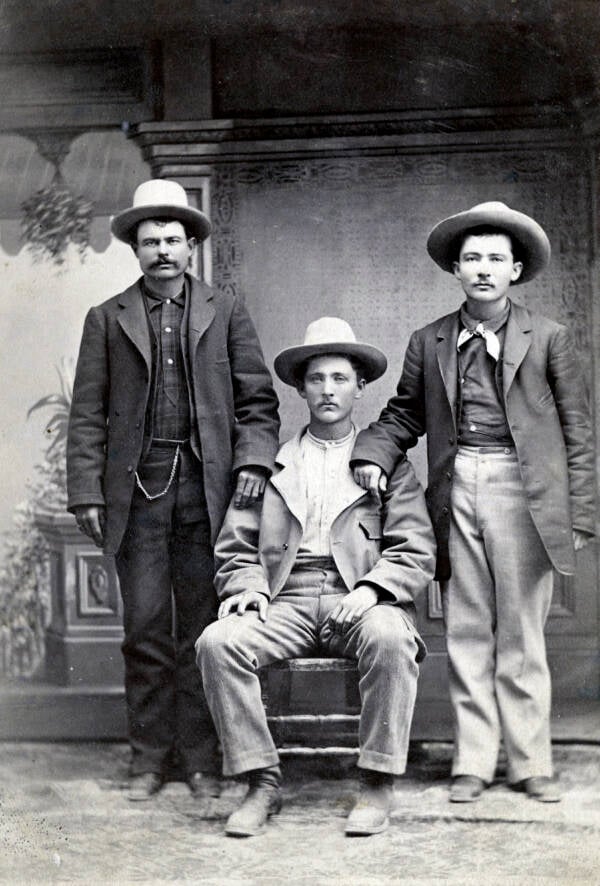

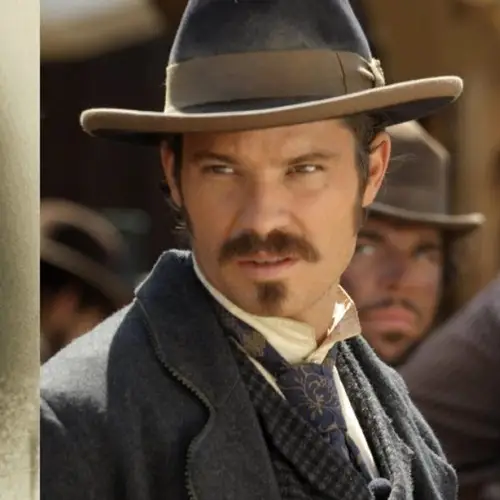

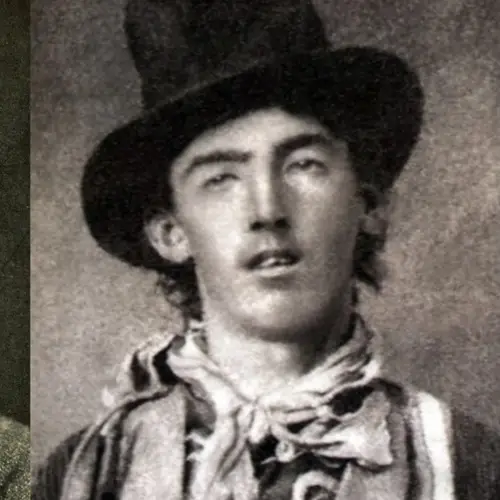

It was also here, on Oct. 26, 1881, that one of the most famous shootouts in the Wild West took place. The gunfight at the O.K. Corral, as it is now known, was a bloody face-off between cowboy outlaws Billy Claiborne, Ike and Billy Clanton, and Tom and Frank McLaury, against local lawmen Wyatt Earp and Virgil Earp as well as Doc Holliday.

As shots were fired on Fremont Street, Cochise County Sheriff John Behan took cover inside the photography studio where he was soon joined by a terrified and unarmed Ike Clanton. C.S. Fly, on the other hand, was out in the action, disarming outlaw Billy Clanton with a Henry rifle.

As the Tombstone Nugget later reported, October 26 was "a day always to be remembered as witnessing the bloodiest and deadliest street fight that has ever occurred in this place, or probably in the Territory."

While Fly didn't get any photographs of the actual gunfight — which only lasted approximately 30 seconds — he did manage to capture both the outlaws and the lawmen on film before and after the bloodshed.

Fly Captured Western Historical Greats

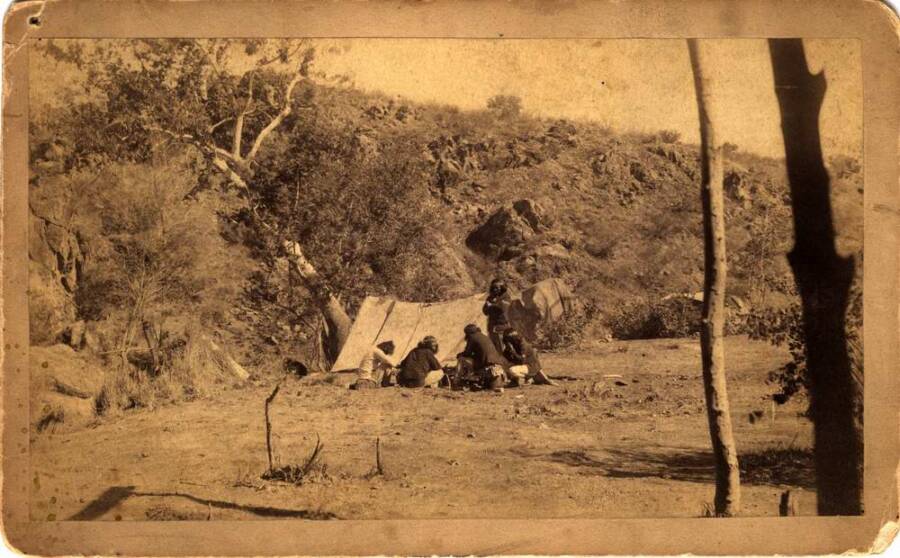

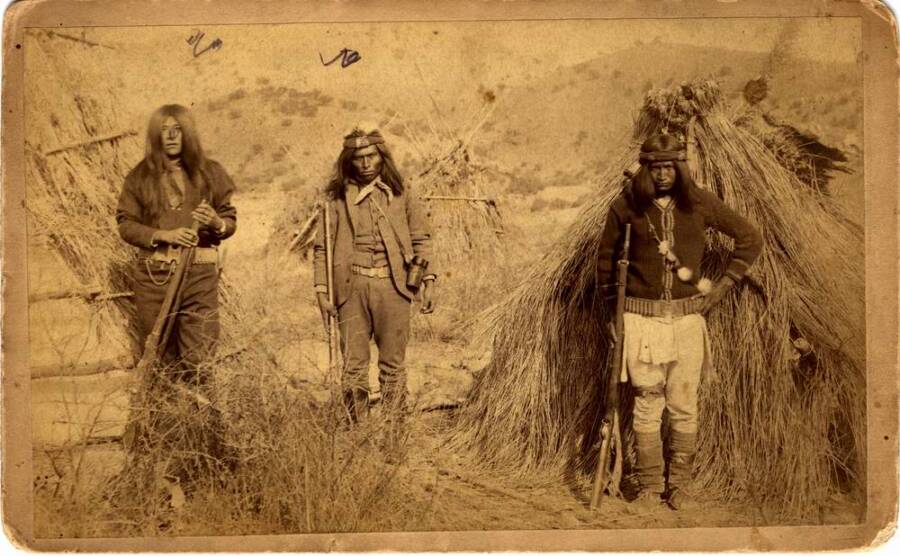

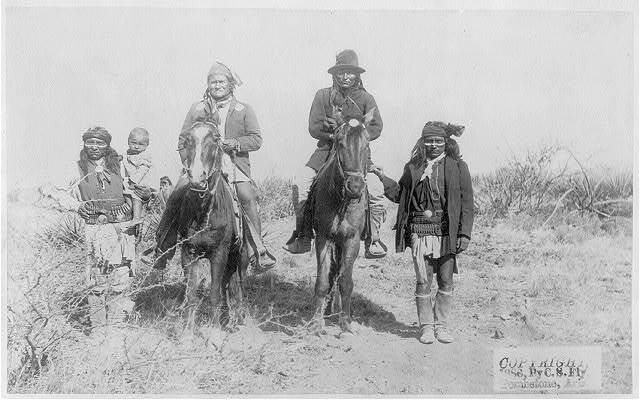

C.S. Fly/Library of Congress C.S. Fly took this photograph of Geronimo, Natches, and Geronimo's son Perico before their surrender to General Crook.

In March, 1886, C.S. Fly heard news of an expected surrender from Apache chief Geronimo. The photographer loaded up his camera, glass photographic plates, and camping gear, and set off with his assistant to capture the historic moment.

Geronimo had refused to meet U.S. Army General George Crook on American soil, so the Arizona military commander went to northeastern Sonora, Mexico for the meeting — with Fly in tow.

On March 23, Fly met General Crook at his campsite in Silver Springs where he asked for permission to record the historic meeting. Permission granted, Fly and his camera joined the two opposing groups on March 25 at a site in the nearby mountains.

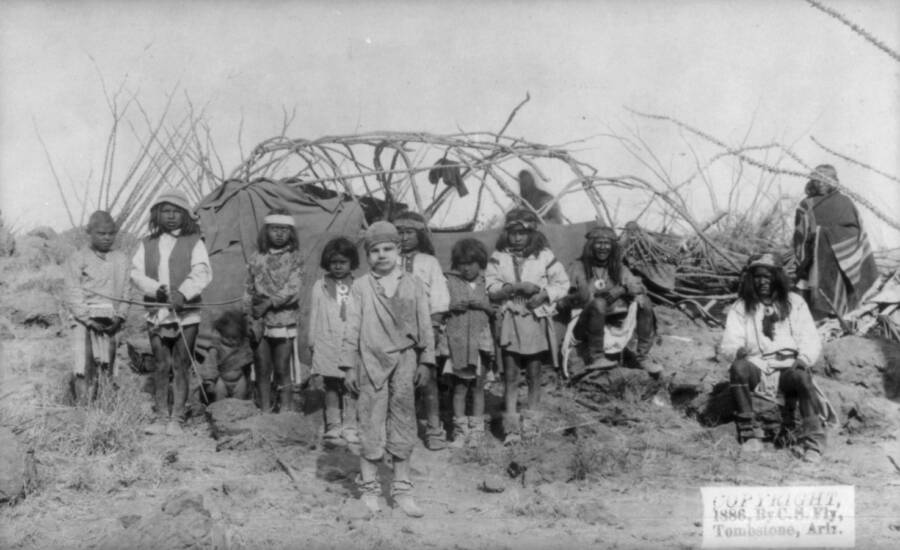

The photojournalist is responsible for capturing the only known images of Native Americans during wartime. And he wasn't shy about it, either.

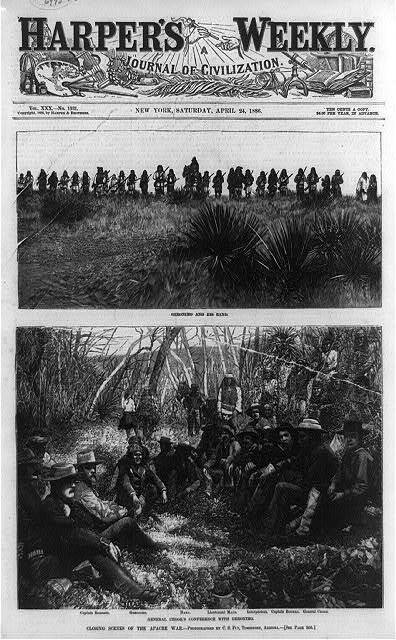

C.S. Fly/Library of Congress After returning to Tombstone, Fly sent these photographs to several publications. Harper's Weekly ended up publishing six of them.

As the Tuscan mayor, C. M. Strauss who was present at the meeting, later said:

"Fly is an excellent artist and he was not a respecter of persons or circumstances, and even in the midst of the most serious interviews with the Indians, he would step up to an officer and say, 'Just put your hat a little more on this side, General. No, Geronimo, your right foot must rest on that stone,'etc., so wrapped was he in the artistic effect of his views."

On March 26, with history forever changed, Buck Fly once again packed up his gear and started the 80 miles back to Tombstone.

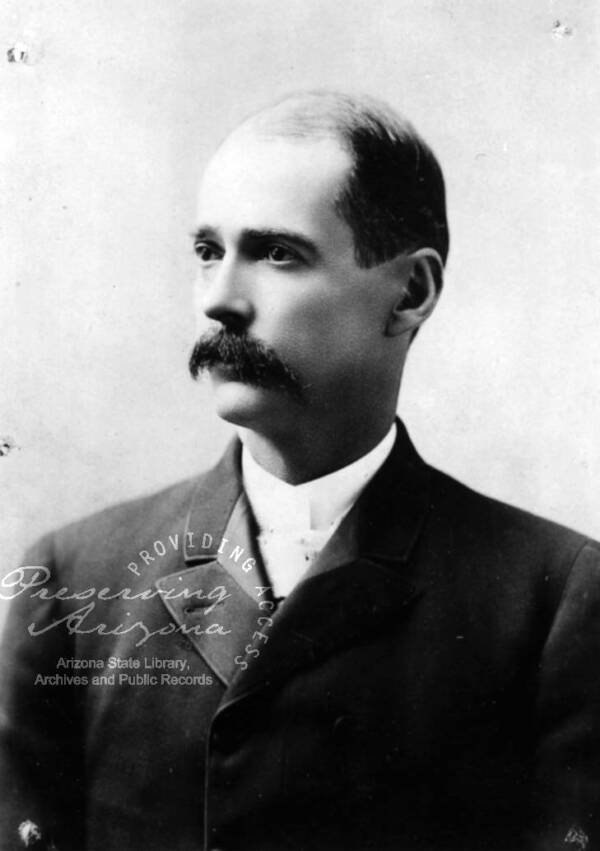

Later Life In The Studio And In The Law

Back at his studio, he made the prints of his photos and sent them off to local publications. Harper's Weekly published six of them, making C.S. Fly a national name.

However, while Fly was making history, he was also falling prey to his own alcoholism. His wife Mollie took their child and separated from him. In 1887, Fly left Tombstone. In his absence, Mollie continued to run Fly's Photography Studio and solidify herself as one of the very few female photographers of the time.

Wikimedia CommonsAfter a fire destroyed the studio, Mollie donated the remaining negatives to the Smithsonian Institute. The couple's gallery has since been rebuilt in Tombstone, Arizona, and is now a tourist attraction.

Between 1887 and 1901, Buck Fly worked as a County Sheriff and a rancher. He toured the West with his camera. On Oct. 12, 1901, the photojournalist passed away and was buried in Tombstone, Arizona.

After his death, Mollie Fly published a collection of her husband's photographs called "Scenes in Geronimo's Camp: The Apache Outlaw and Murderer," and also donated her husband's negatives to the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, D.C.

Now that you've seen C.S. Fly's Wild West, check out Calamity Jane, the notorious frontierswoman. Then, read about Johnny Ringo, the outlaw who faced off against Wyatt Earp.