The Cuban Missile Crisis has been called the crowning victory of John F. Kennedy's presidency, but less favorable parts of the story have been kept under wraps for decades.

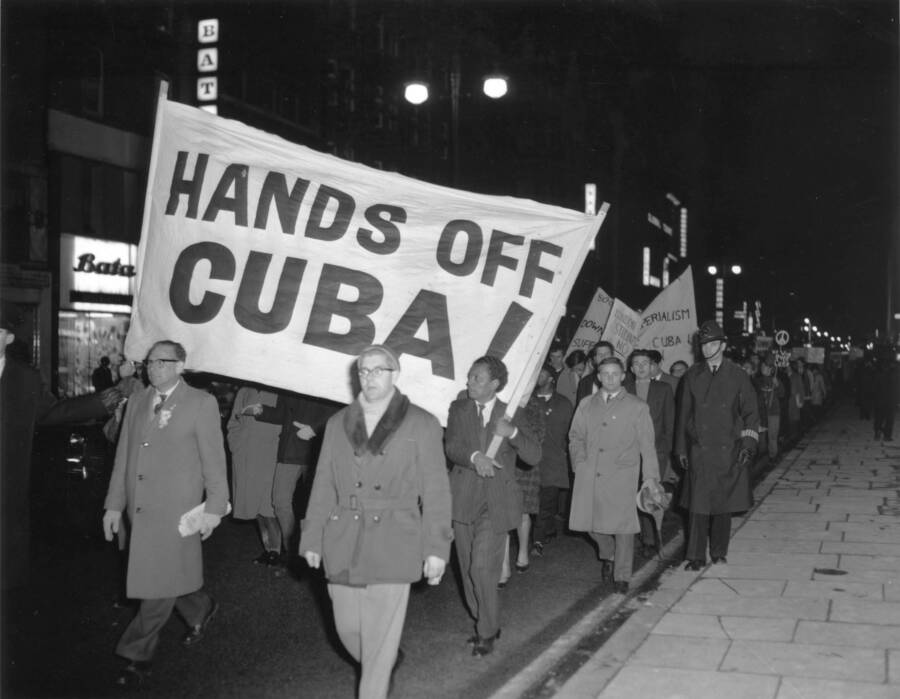

In October of 1962, our world came closer to nuclear war that it has ever been. For 13 days, the world waited tensely through what would become known as the Cuban Missile Crisis, waiting to see if the world's powers could be calmed if the planet would fall under a rain of nuclear devastation.

Today, those 13 days are a part of history that the world has never forgotten – but they're not a necessarily a part of history that the world has ever fully understood.

Here in the West, we've learned the story through the American perspective. To us, it's been a story with clear heroes and villains; one in which the Soviet Union recklessly put the world in mortal peril until – as it has been said – they "bowed to overwhelming U.S. strategic power."

But inside the Soviet Union and inside of Cuba, a wildly different version of the story was being told, with details that would be kept out of the official version of the story in America.

Under an iron curtain and a folder of classified Pentagon papers, the full story of the Cuban Missile Crisis was kept secret for years. But today, it can finally be told.

Inside The Kremlin

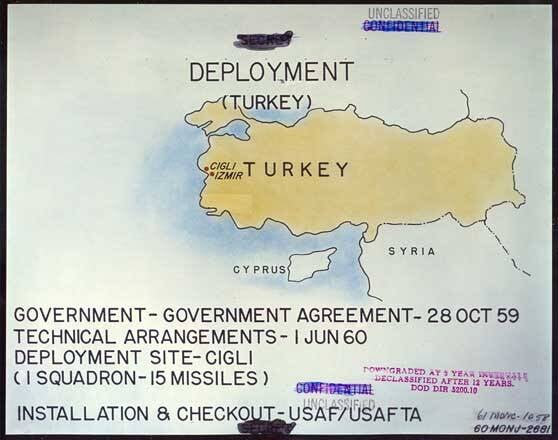

Wikimedia CommonsJupiter Nuclear Missiles deployed in Turkey by the U.S. military. 1962.

When President John F. Kennedy announced to the world that the Soviet Union was building nuclear missile sites in Cuba, he painted Soviet Chairman Nikita Khrushchev as nothing short of a cartoon supervillain.

"I call upon Chairman Khrushchev to halt and eliminate this clandestine, reckless, and provocative threat to world peace," Kennedy said. "Abandon this course of world domination!"

But if, by moving nuclear bombs into firing range of the United States, Khrushchev was recklessly threatening world peace, Kennedy was guilty of that very same crime.

In 1961, the United States had installed a series of intermediate-range "Jupiter" nuclear missiles in Italy and Turkey, where they'd be in range to strike virtually all of the western U.S.S.R. – including Moscow. Plus, the U.S. already had ballistic missiles in Britain aimed at the Soviets.

This, from the Soviet perspective, was the real beginning of the crisis. So in order to keep the U.S. in check, and in order to protect his socialist ally in the Caribbean, Khrushchev moved nuclear missiles into Cuba.

He believed, in part, that the missiles would help balance the power between the United States and the Soviet Union, which was becoming dangerously one-sided. By some estimates, the U.S. had more than 5,000 nuclear missiles capable of hitting Soviet targets, while the Soviets only had 300.

He was also convinced that an American invasion of Cuba was inevitable – despite its failed attempt at one in the April 1961 Bay of Pigs debacle — and the only way to stop it was with nuclear missiles. With that logic, Khrushchev convinced Cuban President Fidel Castro to let him move missiles into his country.

"An attack on Cuba is being prepared," Khrushchev told Castro. "And the only way to save Cuba is to put missiles there."

Kennedy left every one of those details out of his address to the nation; an omission that frustrated Khrushchev to no end.

"You are disturbed over Cuba," Khrushchev would later write to Kennedy. "You say that this disturbs you because it is 90 miles by sea from the coast of the United States of America. But Turkey adjoins us....You have placed destructive missile weapons, which you call offensive, in Turkey, literally next to us."

Inside The Kennedy White House

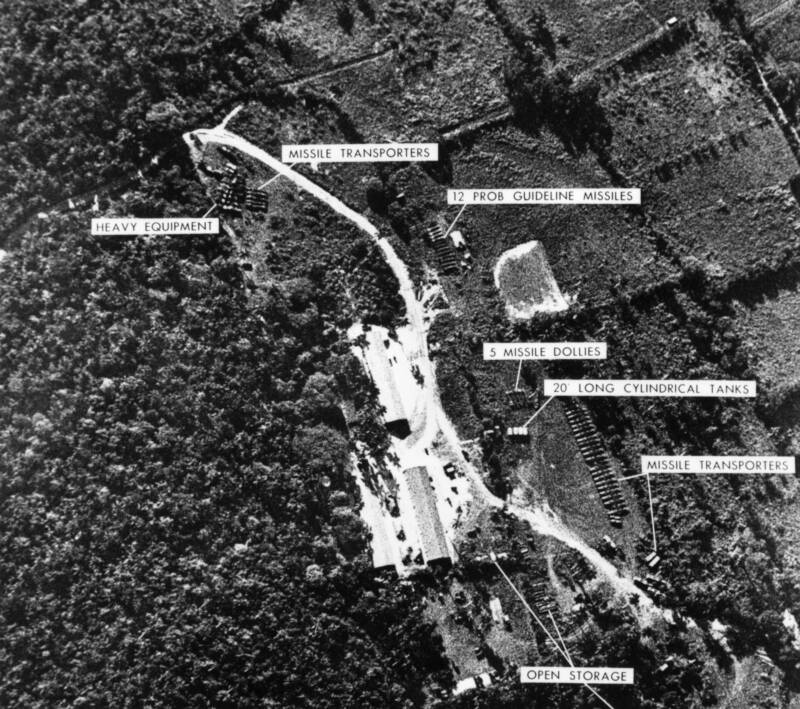

On Oct. 14, 1962, Air Force Maj. Richard Heyser provided Kennedy's Executive Committee of the National Security Council, or ExComm, with 928 photographs capturing the construction of an SS-4 nuclear missile site in the city of San Cristobal in western Cuba.

For the first time, they had proof that the Soviets were transporting nuclear weapons into Cuba. Over the next few days, the news would only get worse; evidence would come through showing that four Cuban missile sites that were already fully operational.

When the news reached the public, it would create mass panic. Americans and civilians in nations around the world would be convinced that this was a sign that nuclear war was inevitable.

But in the War Room, few believed that America was really under any type of nuclear threat.

"It made no difference," Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara would later say. The U.S., he explained, had 5,000 warheads pointed at the Soviet Union, and the Soviet Union only had 300 pointed back at them.

"Can anyone seriously tell me that their having 340 would have made any difference?"

Preparing For The Cuban Missile Crisis

Kennedy, likewise, didn't believe that the Soviets had any intention of firing the missiles. "If they were going to get into a nuclear struggle," he would later explain, "they have their own missiles in the Soviet Union."

Instead, Kennedy's fear was that the Cuban Missile Crisis would affect America politically. The news, he believed, would make people think the balance of power had changed, even if it really hadn't. As he put it: "Appearances contribute to reality."

"Right from the beginning, it was President Kennedy who said that it was politically unacceptable for us to leave those missile sites alone," McNamara recalled in a 1987 interview. "He didn't say militarily, he said politically."

Something had to be done. America couldn't be seen allowing the Soviets to send nuclear weapons to own the U.S.'s greatest sworn enemies. After all, Kennedy had recently campaigned against Richard Nixon on the basis that the Eisenhower administration's policies had sprung a communist regime in the Caribbean.

The ExComm team contemplated a full-scale invasion. The Soviets, they believed, wouldn't do anything to stop it; they would fear retaliation from America's more powerful arsenal too much to raise a finger in Castro's defense.

But Kennedy ultimately refused, fearing that the Soviets would retaliate in Berlin. Instead, he took McNamara's suggestion to set up a blockade around the country to keep Soviet materials out.

The blockade was technically an act of war; Cuba was accepting the Soviets' missiles, and so what the Soviets were doing completely abided by international law. Thus, the Soviets could retaliate with force. But all Kennedy could do was hope that they didn't.

In Havana

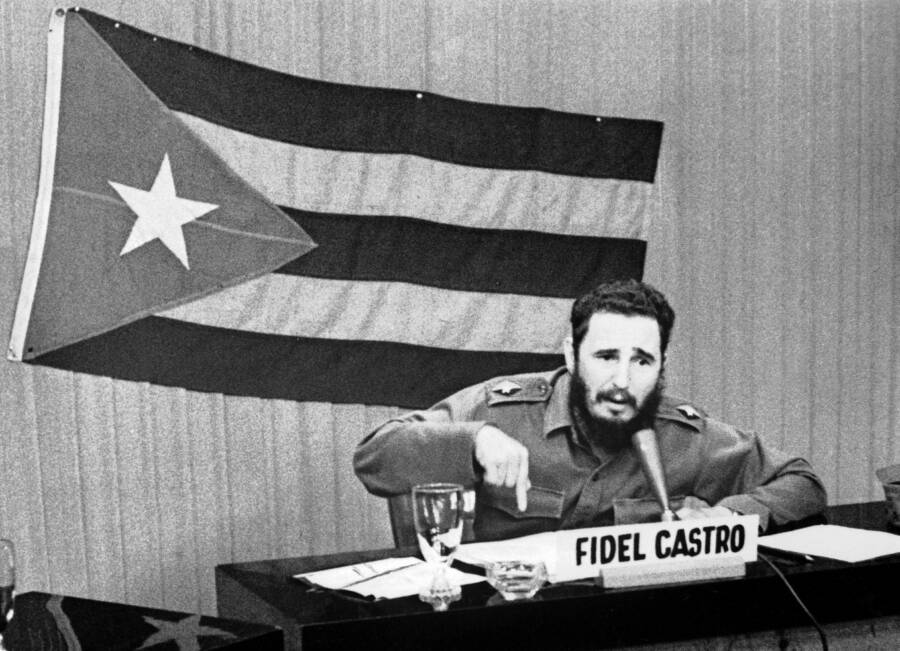

Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone via Getty ImagesCuban Prime Minister Fidel Castro gives a speech, criticizing the United States during the naval blockade of Cuba on October 22, 1962.

Everything, Khrushchev believed, was going more or less according to plan. When the missiles were discovered, he predicted, Kennedy would "make a fuss, make more of a fuss, and then agree."

But Khrushchev hadn't anticipated the real threat to his plans. The greatest danger in the Cuban Missile Crisis, he'd soon learn, wouldn't come from his enemies. It would come from his allies.

In Havana, Castro was ready to fight. He had fully bought into Khrushchev's claims that the U.S. was getting ready to invade, and he was ready to take the whole world down with him.

Castro wrote up a letter to Khrushchev, begging him to launch a full-scale nuclear assault on the United States the second an American soldier set foot on Cuban soil.

"That would be the moment to eliminate such danger forever through an act of legitimate self-defense, however harsh and terrible the solution would be," Castro wrote. Though Krushchev received a slightly different version from his translator: "If they attack Cuba, we should wipe them off the face of the earth."

Castro's second-in-command, Che Guevara, shared every bit of his president's fervor. After the Cuban Missile Crisis ended, he told a reporter: "If the nuclear missiles had remained we would have used them against the very heart of America."

He didn't care if the ensuing nuclear war would have wiped Cuba off the map.

"We must walk by the path of liberation," Guevara said, "even when it may cost millions of atomic victims."

As Khrushchev was quickly learning, hotter blood ran through the Cubans' veins than his own. Desperate to keep things from getting out of control, he urged Castro to stay calm, and even Khrushchev's own men were every bit as willing to fire if provoked.

"The normal military response in a situation like that is to reciprocate," stated one Soviet commander, when asked what he would do if the Americans attacked.

A Hemisphere In Terror

American, Soviet, and Cuban leaders may have talked a big game, but that didn't comfort their people. Existential dread swept over the U.S. and Cuba, as people outside of the annals of government prepared for potential nuclear annihilation.

Marta Maria Darby was a young child in Florida when the news of the crisis hit:

"My family reacted with: The world is going to end, and it had something to do with Cuba. I was seven years old at the time, and it was quite an impression. We sat and thought: Where would they strike first?...I was very afraid. And then the adults in the house started wondering, well, maybe they'll hit New York first. And so I didn't sleep for days. It was quite frightening.?

Margaret was also a young child in America:

"My older brother, who was eight at the time, was terrified. My sisters remember him praying on his knees at his bedside that we would not have a nuclear war. What a horrible thing for a little boy to go through."

The situation was similarly frightening in Cuba, which was still fairly fresh off of its 1959 socialist revolution. Maria Salgado later recalled her "family members from out of town coming in and everyone being in our same hometown because...you know, the world was going to end. So you wanted to be near your family, near your loved ones."

Up In Flames

On Oct. 27, 1962, Soviet Lt. Gen. Stepan Grechko was fed up. For more than hour now, he and his men had been watching an American U-2 spy plane fly over Cuban land. He wasn't going to put up with it any longer.

"Our guest has been there for over an hour," Grechko told his deputy. "Shoot it down."

The man inside that plane was Rudolf Anderson Jr. He went down in flames, becoming the only man to die during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

In the White House, news of Anderson's death brought the crisis to a whole new pitch. The Soviets had drawn first blood; by the plan Kennedy had laid out, it was time for a full-on war.

"Before we sent the U-2 out, we agree that, if it was shot down, we wouldn't meet," McNamara would later explain. "We'd simply attack."

Kennedy alone, however, stopped the American Army from storming Cuban soil. Against the advice of almost every member of ExComm, he ordered his men to stand by and wait until they'd spoken to the Soviets.

It was a decision that very likely saved the world. Castro was intent on firing every nuclear missile he had if an American soldier invaded.

When the president's brother, Robert Kennedy, then the Attorney General, secretly met with Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin at the Justice Department, he threatened: "If one more plane was shot at...that would almost surely be followed by an invasion."

And in Havana, Castro was ready to keep shooting down any planes he saw — no matter what the consequences.

The day before the U-2 plane shot down, Kennedy had caved to his ExComm team and admitted that their advice was right. He couldn't see way out of the Cuban Missile Crisis, he admitted at last, other than an invasion. The U-2 pilot's death cemented this decision in his advisors' eyes, but Kennedy changed course. He wanted to see if they could reach a diplomatic solution first.

Under The Water

Wikimedia CommonsVasili Arkhipov, the man some say saved the world from the brink of nuclear war. Circa 1960.

Before the sun set, the world would skirt nuclear war a second time.

On the very same day, ships in the naval blockade around Cuba detected a Soviet submarine moving beneath them. They dropped "signaling depth charges" on it, beckoning it to come to the surface.

What they didn't know was that the submarine was carrying a tactical nuclear torpedo on board – and that the commander of the vessel, Valentin Savitsky, wasn't afraid to use it.

When the depth charges exploded, the crew of the submarine became convinced that their lives were in jeopardy. "The American hit us with something stronger than the grenades — apparently with a practice depth bomb," one crew member would later write. "We thought: 'That's it, the end.'"

Savitsky ordered his men to retaliate by firing the nuclear torpedo up to destroy the Navy ships attacking them. "We're going to blast them now!" he barked. "We will die, but we will sink them all. We will not become the shame of the fleet!"

Had the crew launched the missile, it is very likely that the U.S. Army would have retaliated in kind and a nuclear war would have begun. But one man stopped it from happening: Vasili Arkhipov.

By Soviet rule, Savitsky wasn't allowed to fire at the missile unless he got consent from the two other senior officers on board. One agreed – but the other, Arkhipov, stood his ground and refused to approve the nuclear launch.

Arkhipov argued that the depth charges weren't proof that a war had begun; the Americans might just be trying to get them to surface. He stayed firm in his refusal, and convinced the crew to head back to Russia peacefully.

"Vasili Arkhipov saved the world," Thomas Blanton, Director of the National Security Archive, would later say.

Behind Closed Doors

After two nearly apocalyptic crises, Kennedy and his advisor lost all faith that the Cuban Missile Crisis would end in anything other than a disaster.

"The expectation was a military confrontation by Tuesday," Robert Kennedy would later write in his book, Thirteen Days: A Memoir of the Cuban Missile Crisis. "Possibly tomorrow."

But in Moscow, Khrushchev was every bit as terrified as the Americans. According to his son, Sergei, "Father felt the situation was slipping out of control....That was the moment when he felt instinctively that the missiles had to be removed."

Dobrynin met with Robert Kennedy once more, and Kennedy admitted: "The President is in a grave situation and does not know how to get out of it."

The Kennedys, Robert said, were doing everything they could to keep a war from happening; but in a democracy, he warned, the President's power was limited. "An irreversible chain of events could occur against his will."

How Was The Cuban Missile Crisis Resolved?

Khrushchev and Kennedy reached an agreement: The Soviets would take their missiles out of Cuba and, in exchange, the Americans would take their missiles out of Turkey. But Kennedy insisted on one single clause: No one was allowed to know that the missiles in Turkey were part of the bargain.

Khrushchev agreed. Publicly, Kennedy was allowed to tell the world that all he'd given the Soviets was a promise not to invade Cuba – but privately, the Soviets had gotten what they'd wanted.

The missiles in Turkey were gone, the threat of a Cuban invasion was over, and all he'd had to give up was something he didn't have before the Cuban Missile Crisis began.

In a sense, Khrushchev had won – but nobody knew. In the public view, he'd been humiliated, and the blow was so horrible that it ended his career.

"The Soviet leadership could not forget a blow to its prestige bordering on humiliation," Dobrynin would later write. Two years later, in 1964, Khrushchev was dismissed as chairman. Many who called for him to go specifically cited his role in the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Kennedy, on the other hand, came out of the story a hero. Today, he's remembered by many as one of the greatest American presidents; a title experts credit, in a large part, to his handling of the crisis.

After learning about the Cuban Missile Crisis, learn the story of Castro's Cuban Revolution. Then, see how life was behind the iron curtain with these incredible photos of East Germany.