Countless people around the world have been captivated by ancient Egypt since Roman times, but especially after King Tutankhamun's tomb was discovered in 1922, Egyptomania spread across Europe and the United States, influencing art, fashion, and more.

For more than 2,000 years, people around the world have been fascinated by ancient Egypt. This interest, known as Egyptomania, has peaked several times throughout history, most notably following Napoleon Bonaparte’s Egyptian campaign in the late 18th century and the rediscovery of King Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922.

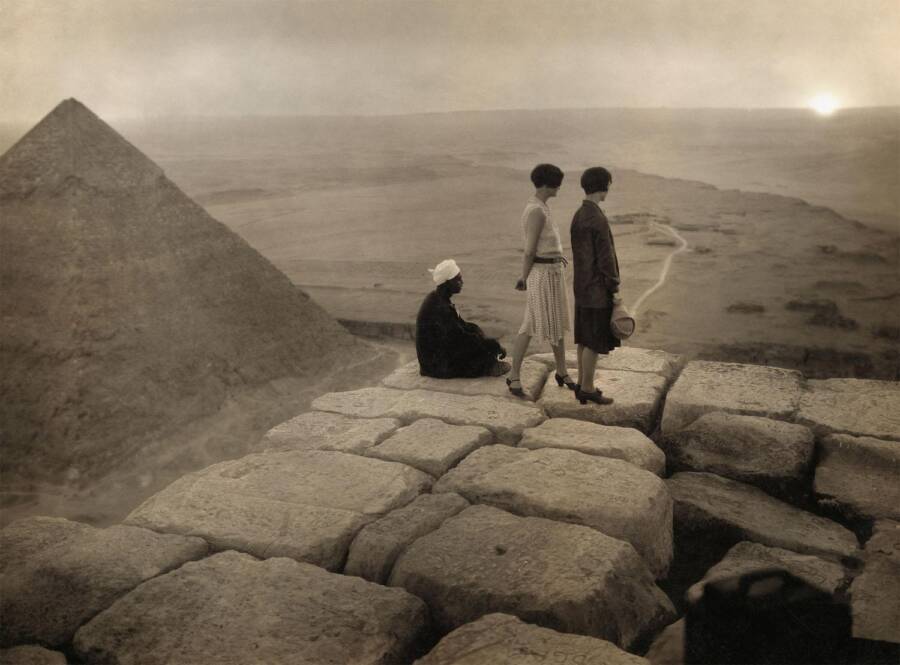

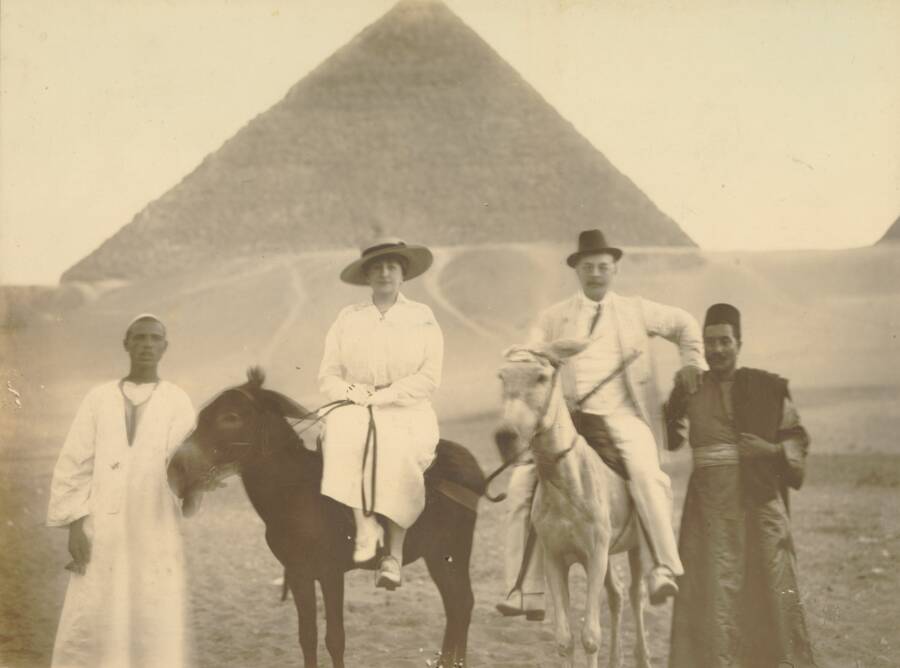

Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, those who were able to afford it flocked to places like Giza and Luxor to see the past for themselves. Everyone else experienced ancient Egypt through art, architecture, film, fashion, and literature.

The Art Deco design trend of the early 1900s was heavily inspired by Egyptian motifs, and rumors of a "mummy's curse" in King Tut's tomb spawned dozens of mystery novels and Hollywood hits. Even modern businesses, such as the Luxor hotel and casino in Las Vegas, have capitalized on Egpytomania.

Below, read more about the obsession with ancient Egypt that has gripped the world since Roman times. And above, look through 33 photos that reveal the extent of the craze.

Early Fascination With Egypt In Ancient Greece And Rome

Although the term "Egyptomania" didn't exist thousands of years ago, the sentiment surely did. Interactions between the ancient Greeks, Romans, and Egyptians have been well chronicled — and even entered popular culture thanks to the relationship between Marc Antony and Cleopatra.

But even before the tragic demise of the ill-fated lovers, the Greeks and Romans found themselves captivated by Egyptian culture. Although they are all ancient to modern humans, keep in mind that "ancient" is a rather broad term. In the historical timeline, the Egyptian kingdom at its height predates even the ancient Greeks and Romans by hundreds of years.

This is why an Egyptian priest once said to a visiting Greek, "You Greeks are children."

What we typically refer to when we speak of "ancient Greece" is the period in which city-states like Athens and Sparta emerged, roughly around the eighth century B.C.E., following the Greek Dark Ages (the Bronze Age collapse of the Mycenaean civilization). For comparison, the peak of ancient Egypt's power occurred during the New Kingdom, between 1550 and 1070 B.C.E. The Roman Republic didn't come along until 509 B.C.E.

Public DomainEuropean tourists in Egypt circa 1925.

Classical era Greeks interacted with the ancient Egyptians often, and historians like Herodotus noted many similarities between Greek and Egyptian deities, suggesting that Egyptian religion likely had a large influence on the Greek pantheon. A similar observation could be made between Egyptian and Greek architecture, particularly when it came to temple design.

Greek scholars, including Pythagoras and Plato, are also believed to have studied in Egypt, where they developed the knowledge of mathematics, astronomy, and philosophy that they later integrated into Greek thought.

Hundreds of years later, Egyptomania struck Rome. Like the Greeks, the Romans took architectural cues from the Egyptians. However, they took it a step further by importing obelisks and statues straight from Egypt to their cities following the Roman conquest of Egypt in 30 B.C.E.

Of course, this fascination did not fade even after the collapse of the Roman Empire. More than 1,000 years later, another wave of Egyptomania swept throughout Europe — thanks to none other than Napoleon Bonaparte.

How Napoleon's Campaign Led To Egyptomania In Europe

Public DomainThe Battle of the Pyramids (1810) by Antoine-Jean Gros depicts Napoleon's invasion of Egypt in July 1798.

Starting in 1798, Napoleon led a significant military and scientific campaign in Egypt. Aiming to undermine British access to India and expand French influence, Napoleon invaded Egypt with his military forces and more than 150 scientists, engineers, and artists, collectively known as "savants."

According to the National Army Museum, Napoleon made his intentions clear from the start, saying, "To destroy England truly, we shall have to capture Egypt."

The multidisciplinary team was tasked with studying and documenting Egypt's antiquities, natural history, and culture, which led to several significant achievements, including the establishment of the Institut d'Égypte in Cairo and a vast publication of the savants' collective observations known as the Description de l'Égypte.

The most significant outcome of this campaign, however, was the discovery of the Rosetta Stone, an artifact that proved instrumental in deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphs.

Napoleon's military campaign was ultimately unsuccessful, but the artifacts that the French brought back from Egypt and the publication of the Description de l'Égypte kickstarted a new wave of Egyptomania across Europe. Egyptian Revival architecture became a popular design choice, often incorporating motifs like sphinxes, obelisks, and pyramidal structures.

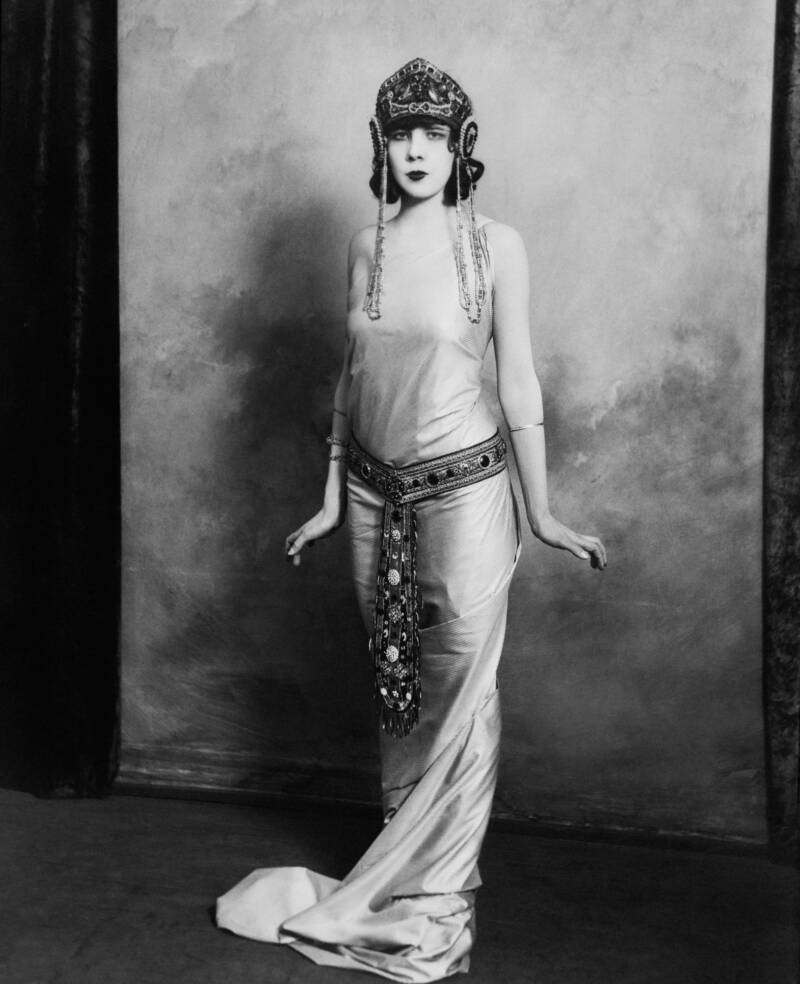

Artists and writers also drew inspiration from Egyptian themes, producing works that romanticized and reimagined ancient Egyptian life and mythology. Likewise, Egyptian motifs started appearing commonly in the fashion of the era, with elements like lotus flowers, scarabs, and hieroglyph patterns adorning clothing, jewelry, furniture, and other household items.

Naturally, this new, widespread fascination with Egypt prompted further archaeological explorations and a deeper scholarly interest in Egyptian history as well. This soared to new heights a century later when King Tutankhamun's tomb was rediscovered in 1922.

Tutmania Of The 1920s And Egyptomania In The United States

After explorer Howard Carter found the long-lost tomb of King Tutankhamun, a new global phenomenon known as "Tutmania" took the world by storm.

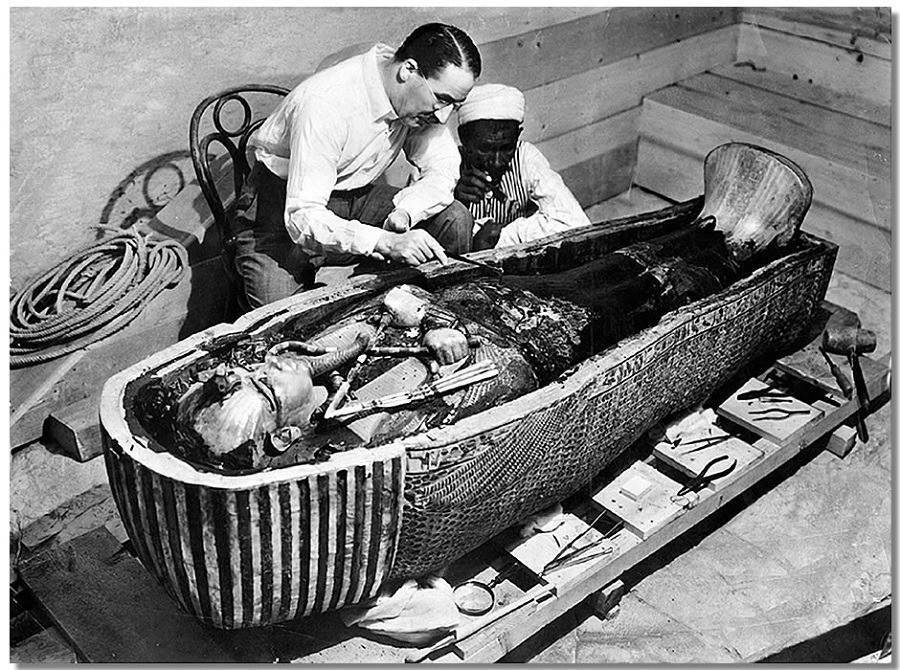

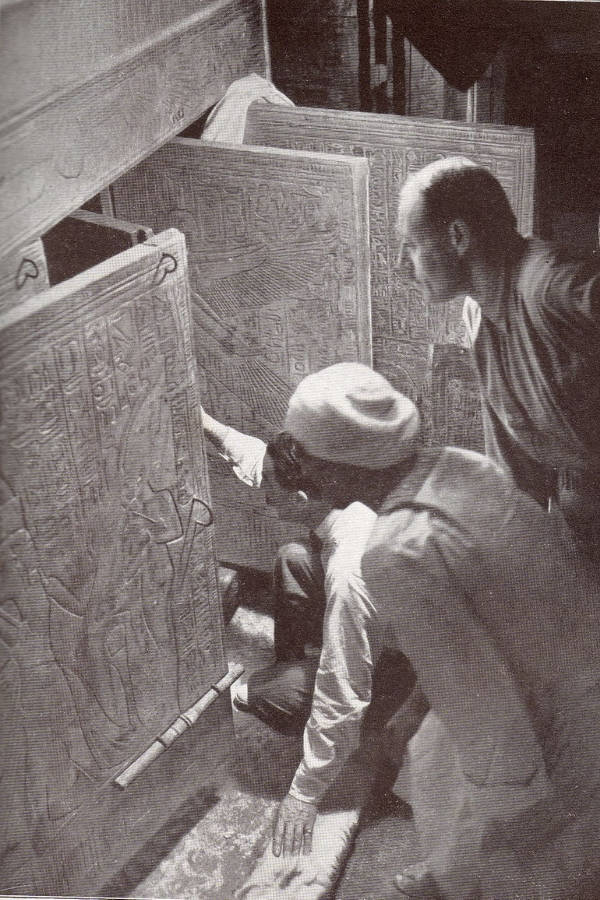

When Carter first came across Tut's tomb, he wrote in his notebook that it was reminiscent of the "property-room of an opera of a vanished civilization." The "wonderful things" he found inside included numerous ancient artifacts like King Tut's sandals, jars full of ancient alcohol, and, of course, the Boy King's sarcophagus. Over the next 10 years, Carter and his team extracted more than 5,000 artifacts from the royal's burial place to show off to the world.

Public DomainHoward Carter looking into King Tut's tomb in 1924.

Carter also spent a lot of time traveling and talking about his work. In particular, he spoke often at both the Cleveland Museum of Art and the Detroit Institute of Arts, leading him to be credited with bringing Egyptomania to the United States.

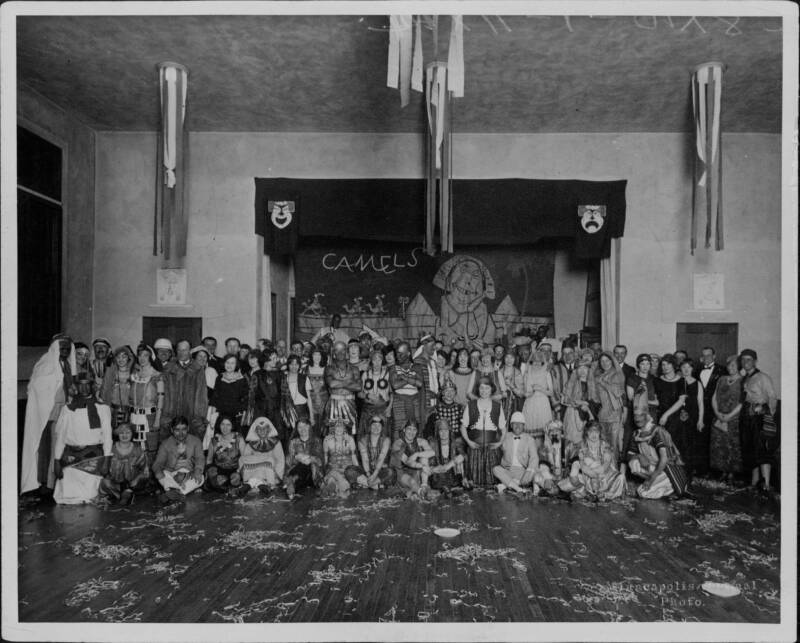

Americans were captivated by Carter's discovery. It was a media firestorm, and as Carter traveled about with the ancient treasures, the designs and motifs featured on them also came to be incorporated into American fashion and architecture. Egyptian symbols were frequently combined with the Art Deco style, helping to craft the aesthetic of the '20s.

Like in Europe, the arts also picked up on this trend. Many classic Hollywood films were centered around ancient Egypt well into the 1960s and '70s — the most famous example being Cleopatra (1963) starring Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor. Many of them centered on the legend of the "mummy's curse" associated with King Tut's tomb.

Ancient Egyptian influence was pervasive throughout all of American culture in the 1920s. Consumer goods featured Egyptian-inspired designs, and architectural trends incorporated Egyptian motifs. Everywhere you looked, ancient Egypt was looking back.

In one 2003 study, the University of Delaware's Katherine A. Hunt observed that "through Egyptian imagery, Americans were able to engage issues concerning society in the 1920s: class disparity, faith, shaping one's identity, definitions of beauty, the role of women in modern society, and color politics in the African-American community."

Public DomainThe Sphinx of the Fontaine du Palmier in Paris, which was built between 1806 and 1808.

Hunt suggested that the fascination with such an "exotic location" was representative of a "fundamental uncertainty underlying American culture in the twenties."

In a sense, the American Egyptomania craze of the 1920s was a form of escapism. It allowed people to discuss the issues of the modern day through the lens of ancient history while also providing something permanent to hold on to. The fact that the Sphinx and the pyramids had remained intact for thousands of years offered reassurance that, even though the times were changing, some things would always remain the same.

After reading about how Egyptomania took over the world throughout history, learn all about the khopesh, the curved Egyptian sword that helped establish an empire. Then, discover the real reason why so many Egyptian statues have broken noses.