Between 1926 and 1930, Elizebeth Friedman decoded 20,000 messages per year in hundreds of different code systems. Even more incredibly, she decoded them all in a time without computers.

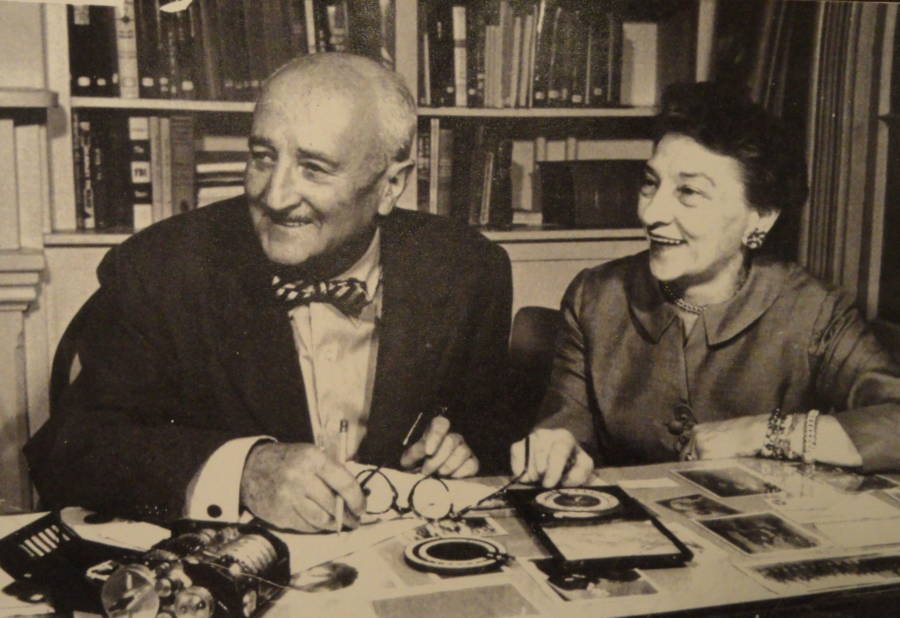

Wikimedia CommonsElizebeth Friedman with her husband.

Elizebeth Friedman would never have thought that her love of Hamlet and Macbeth would lead her to a life of fighting smugglers and Nazi spy rings. But that’s exactly what happened to the Indiana native.

When she left college in 1915, she got a job at the Newberry Research Library in Chicago due knowledge of Shakespearean plays.

Friedman discussed her passion for The Bard with the librarian who interviewed her for the job. The librarian then made a phone call to a wealthy businessman named George Fabyan, who shared Friedman’s great interest in the plays.

The phone call would change Friedman’s life.

Fabyan was interested in Shakespearean plays because he believed that they contained secret messages proving that the philosopher Francis Bacon had been the plays’ real author. Fabyan’s obsession with this idea drove him to hire a woman named Elizabeth Wells Gallup to work at his cryptology laboratory and discover the messages.

When the librarian informed Fabyan over the phone of Friedman’s love and knowledge of the plays, Fabyan concluded that Friedman would be of good help to Gallup. So he hired Friedman to work at the laboratory.

Despite having little background in mathematics, Friedman developed great codebreaking skills during her time at the laboratory. After several years of working there, she lent these skills to the U.S. Treasury Department.

The U.S. Treasury Department recruited Friedman in 1921 to help the U.S. Coast Guard fight liquor smuggling, which had increased because of Prohibition. Liquor smugglers had been using coded radio messages to prevent the Coast Guard from finding out about their operations.

Friedman helped the Coast Guard by decoding the smugglers’ messages. Between 1926 and 1930, she decoded 20,000 of these messages per year in hundreds of different code systems. Even more incredibly, she decoded all of these messages at a time when there were no computers to assist codebreakers.

Near the end of the decade, she began to testify against the smugglers whose messages she had decoded.

Some of the smugglers that she testified against were quite dangerous. In fact, three of them were lieutenants of the notoriously murderous gangster Al Capone.

But Friedman was brave and did what was necessary to get these gangsters convicted. Following the start of WWII, she went up against an even more dangerous group of malicious people–the Nazis.

During the war, the Nazis sent spies to South America to gather information on U.S. and British military capabilities. The spies also wanted to bring about military coups that would make South American governments more supportive of Nazi Germany.

Wikimedia CommonsA map showing how much Nazi espionage went on in Latin America during World War II.

Friedman and her team of codebreakers in the Coast Guard responded by shifting their focus from decoding smugglers’ messages to decoding those of the spies. Thanks to the codebreakers’ efforts, every Nazi spy network in South America was destroyed.

Sadly, Friedman and her team’s great contributions to the American war effort have gone largely unrecognized.

Following the destruction of the Nazi spy networks in 1944, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover wanted his organization to have all the credit for their downfall. So he launched a publicity campaign promoting the idea that the FBI was solely responsible for the networks’ destruction.

Unfortunately for Friedman, the world had no way of knowing that Hoover was robbing her of credit since records of Friedman’s service to her country during the war were classified.

Furthermore, for reasons of national security, the government forbade her from talking about her service. So she could not speak out against Hoover’s publicity campaign.

To this day, many Americans are unaware of how important the Shakespeare fangirl was to their country’s struggle against Nazi espionage.

Next, read about the true story behind Hacksaw Ridge’s Desmond Doss. Then read about the Nazi submarine that sank because its toilet malfunctioned.