Andrew Johnson, Bill Clinton, and Donald Trump were the only three U.S. presidents to ever be impeached — although Richard Nixon came close.

In January 2021, Donald J. Trump became the first U.S. president to be impeached twice. The last impeachment in U.S. history had been in the late 1990s against Bill Clinton, over statements he made to investigators about his affair with White House intern Monica Lewinsky.

But how many presidents have been impeached? Before Clinton, you’d need to return to the mid-70s when the threat of impeachment was raised against Richard Nixon — though he wasn’t actually impeached. And to find impeached presidents further back than that, you’d need to return a whopping 153 years ago to Andrew Johnson.

Public Domain/Getty ImagesAndrew Johnson, Bill Clinton, and Donald Trump all faced impeachment inquiries — in Trump’s case, two.

In order to impeach a president, the House has to pass articles of impeachment — charges, essentially — by a simple majority. If the House passes at least one of these articles, the president has been impeached, but that still doesn’t remove them from office.

For that, the president must be put on trial by the Senate, and a conviction requires a two-thirds supermajority.

As recent history shows, despite Trump’s two impeachments — one in December 2019 over his Ukraine foreign policy, the other in January 2021 over the Jan. 6 Capitol Hill riots — he was not convicted. So how did the process play out against the only other impeached presidents? Let’s take a look.

The 1868 Impeachment Inquiry Of Andrew Johnson

Wikimedia CommonsAndrew Johnson assumed the presidency after Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, just 42 days after he took office as vice president. Three years later, he was impeached.

The impeachment of President Andrew Johnson began on February 24, 1868.

Johnson assumed the presidency three years earlier, just 42 days after Abraham Lincoln was assassinated. The Civil War had just killed more than 600,000 people, and white leaders in the south were still staunchly opposed to granting rights to Black Americans.

Both the House and Senate were two-thirds “Radical” Republican, however, and this congressional majority established quite clearly that Reconstruction would happen — with the enforcement of the U. S. military. For a time, they thought Johnson was on their side as well.

But then Johnson’s true feelings toward Reconstruction came out. It turned out that Johnson, a Democrat from Tennessee, opposed political rights for freedmen and wanted to grant clemency to any former Confederates who were willing to pledge a loyalty oath to the United States. All the southern states had to do to reenter the Union was ratify the 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery.

The Radical Republicans thought that Johnson’s plan would let the South off too easily. With a veto-proof majority in both houses of Congress, they pushed through two new amendments the South would have to ratify — the 14th and 15th — which granted full political rights, including the right to vote, to all freedmen.

They also enacted a sneakier law in 1867 tailor-made for Johnson called the Tenure of Office Act. The law restricted the president from removing certain officials from office without Senate approval.

Defiant, Johnson fired his Secretary of War, Edwin M. Stanton — the only member of his cabinet against his Reconstruction policy — during the Congressional recess in the summer of 1867. Johnson replaced Stanton with Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, but when the Senate sought to reinstate Stanton a few months later, Grant realized the hornet’s nest he was in and resigned.

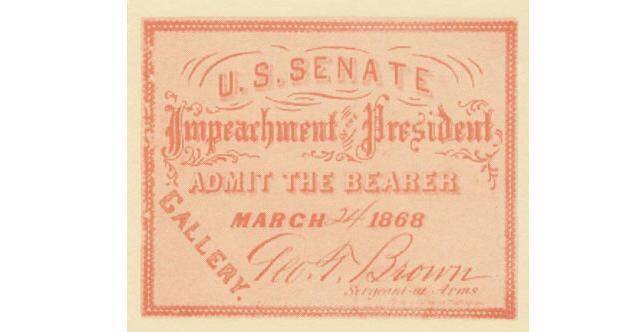

National Park ServiceOne thousand tickets were printed for every day of Johnson’s Senate trial, after the House impeached him. The trial was the entertainment event of the year.

Enraged at Congress, Johnson ignored Stanton’s appointment and picked Maj. Gen. Lorenzo Thomas to fill the secretary position. This was a direct violation of the Tenure of Office Act, and articles of impeachment were drawn up within days.

There were, in total, 11 articles of impeachment drafted by the House, almost all related to Johnson’s actions around Stanton and the Tenure of Office Act, though with the notable charge of making speeches in an attempt to bring “disgrace, ridicule, hatred, contempt and reproach [to] the Congress of the United States,” and to “impair and destroy the regard and respect of all the good people of the United States for the Congress.”

Johnson became one of the few impeached presidents when the House voted to proceed against him on Feb. 24, 1868. On March 5, Johnson’s Senate trial began, with thousands of Americans desperate to nab tickets for the entertainment event of the year.

On May 16, however, the effort to convict Johnson failed by just one vote in the Senate. Republicans still hated him, but enough were compelled to preserve the integrity of the presidential office. Johnson served the rest of his term, albeit with an almost total lack of credibility and power.

How President Richard Nixon Resigned Before He Could Be Impeached

Wikimedia CommonsPresident Richard M. Nixon was almost impeached, but resigned before the process could move forward.

Technically, President Richard Nixon’s Watergate saga didn’t end with him an impeached president, since he resigned before it could get to that point, but by the time Nixon resigned, the House and the Senate had collected enough evidence to move forward with the impeachment process.

Nixon’s impeachment proceedings largely stemmed from his complicity in the June 17, 1972 break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate office complex in Washington, D. C. The Nixon administration tried at every step to prevent any cooperation with the House, spawning a constitutional crisis.

But it turned out that Nixon had secretly tape-recorded private conversations in the Oval Office, and that some of those recordings explicitly showed Nixon himself trying to use his presidential powers to halt the FBI’s investigation of the Watergate break-in.

On July 24, 1974, the Supreme Court finally forced Nixon to turn over the tapes. The tapes were damning, and if Nixon had stuck around long enough to proceed to an impeachment trial, then he would have had to contend with a majority-Democratic House and Senate. It was clear Nixon would be impeached, and soon.

While many were considered, the three articles of impeachment that were approved by the House Judiciary Committee were obstruction of justice (related to the Watergate break-ins and its attempted coverup by Nixon and his staff, as well as withholding the infamous Nixon White House Tapes), abuse of power, and contempt of Congress.

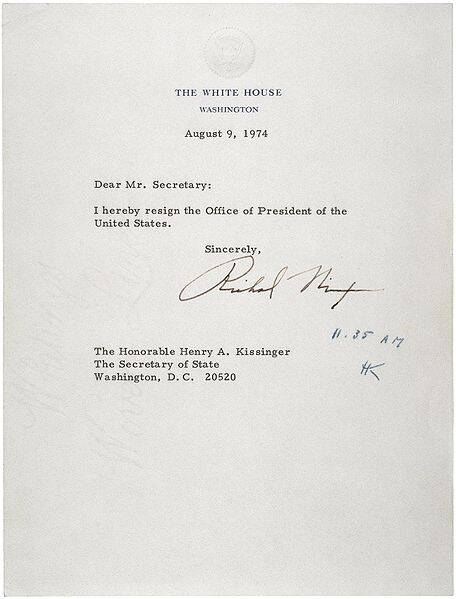

But the full House wouldn’t get to vote on impeachment, as Nixon resigned on August 9, 1974.

“I have never been a quitter. To leave office before my term is completed is abhorrent to every instinct in my body,” Nixon said in a televised speech that attempted to spin his presidency as a win for the U.S. “To have served in this office is to have felt a very personal sense of kinship with each and every American. In leaving it, I do so with this prayer: May God’s grace be with you in all the days ahead.”

Wikimedia CommonsPresident Richard Nixon’s resignation letter. August 9, 1974.

At noon the next day, he gave the reins of the presidency to Vice President Gerald Ford. Ford pardoned Nixon just a month later, protecting him from potential criminal indictment or prosecution.

President Bill Clinton’s Impeachment And Acquittal

Wikimedia CommonsPresident Bill Clinton wasn’t impeached for having an affair with Monica Lewinsky, per se. But he was impeached for lying about it.

Bill Clinton’s presidency nearly ended when the Republican-controlled House passed two articles of impeachment.

The House’s charges were largely informed by Independent Counsel Kenneth Starr, who was originally appointed in 1994 to investigate a real estate company called Whitewater, in which the Clintons had invested in the 1970s and 80s.

But the investigation eventually expanded to include allegations of sexual harassment against President Clinton, after former Arkansas government employee Paula Jones filed a lawsuit against the president in May 1994 for propositioning her while he was governor of the state.

And then, in January 1998, the public caught wind of a totally separate scandal that had been brewing behind closed doors for months: Clinton’s alleged affair with then-White House intern Monica Lewinsky.

Clinton’s and Lewinsky’s sexual acts had been consensual, but according to Starr’s report, Clinton had instructed her to lie to investigators about their affair. What’s more, Starr contended that Clinton himself had lied to a grand jury when he told them “There’s nothing going on” between him and Lewinsky.

“It depends on what the meaning of the word ‘is’ is,” Clinton later clarified. “If ‘is’ means is and never has been, that is not — that is one thing. If it means there is none, that was a completely true statement … If someone had asked me on that day, are you having any kind of sexual relations with Ms. Lewinsky, that is, asked me a question in the present tense, I would have said no. And it would have been completely true.”

To Starr, Clinton’s careful wording amounted to a lie — and House Republicans agreed. They drew up and approved articles of impeachment declaring Clinton had committed perjury and obstruction of justice. To Clinton’s supporters, however, Starr’s years-long, $80 million investigation was much ado over two relatively minor charges.

The House approved two out of four articles of impeachment, almost completely along party lines, on Dec. 19, 1998. In the Senate, which was also Republican-controlled, enough members of the opposite party voted against impeachment to keep Clinton in office. On Feb. 12, 1999, the overall vote tally was 50-50 on the obstruction of justice charge and 45-55 not guilty on the perjury charge.

There were some civil repercussions for Clinton, including the inability to practice law for five years and some fines. In December 1999, one year after Clinton’s impeachment, two-thirds of the American public said the impeachment trials had been harmful to the country.

The Two Impeachments Of President Donald J. Trump

Wikimedia Commons ImagesThe House conducted an impeachment investigation into President Donald Trump over his supposed quid pro quo with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky.

President Donald Trump is just the fourth U.S. president to face the impeachment process. But early this year, he also became the first to be impeached twice.

Trump’s opponents called for his impeachment practically since day one of his presidency, but the first impeachment inquiry was kick-started when an anonymous whistleblower submitted a letter to the intelligence community’s inspector general alleging that Trump had urged Ukraine’s president to investigate former Vice President Joe Biden, his eventual opponent in the 2020 presidential race, and his son Hunter.

The whistleblower alleged in the letter that, “after an initial exchange of pleasantries, the president used the remainder of the call to advance his personal interests. Namely, he sought to pressure the Ukrainian leader to take actions to help the president’s 2020 reelection bid.”

This all supposedly happened in a phone call on July 25, at a time when Trump was holding up $400 million worth of military aid to Ukraine.

When news of the phone call broke, the White House released a transcript of the phone call. In the transcript, right after Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky brings up the military aid, Trump asks for a “favor” and proceeds to bring up the Robert Mueller investigation and then Biden. To many, it appeared Trump was establishing a quid pro quo.

On the heels of the Ukraine revelations, Trump asked China to investigate Biden on national television.

Although Trump was eventually acquitted on two charges, largely along party lines, it wasn’t the end of impeachment for the 45th president.

After the January 6, 2021, riots by his supporters at Capital Hill, Congress lodged a single article of impeachment against Trump with just days left in his term. The charge was that Trump, with his false allegations of a stolen election and speech just before the riots had deliberately instigated the violence.

The unprecedented trial of Trump for incitement of insurrection against the U.S. government went on after he had already left office — and he was again acquitted. However, the second proceedings garnered the most votes ever by a president’s own party in favor of impeachment, as well as seven Republican votes to convict.

And thus — for the time being — Donald J. Trump remains the last of the impeached presidents.

After learning about the impeached presidents of U.S. history, take a look at 21 shocking things American presidents have said (and done). Then, learn about members of the KKK who became senators and Supreme Court justices.