In 1605, Guy Fawkes and 12 other English conspirators tried to assassinate King James I by blowing up Parliament. But just before the explosion was supposed to happen, Fawkes got caught red-handed.

The visage of Guy Fawkes has become a cultural symbol in recent years, both from the use of Fawkes’ likeness in the movie V for Vendetta and the subsequent adoption of the mask by the “hacktivist” group Anonymous. But while some see Guy Fawkes as a freedom fighter — much like the character V in the famous film and graphic novel — others regard him as a terrorist for his role in planning the failed Gunpowder Plot of 1605.

Fawkes was part of a small group of English Roman Catholics who had grown tired of England’s Protestant rule in the early 17th century. So, in order to restore Catholic rule in the country, this group of conspirators devised a plan to blow up the Parliament and assassinate King James I.

Their plan, however, was foiled when Guy Fawkes was discovered in the Parliament cellar just after midnight on November 5, 1605. Soon afterward, he and his co-conspirators were tried and executed for treason.

In the United Kingdom, November 5th is still known as Guy Fawkes Day — or Guy Fawkes Night or Bonfire Night — and it involves a number of celebrations in remembrance of the failed assassination attempt, including bonfires, fireworks, and burning effigies of Guy Fawkes.

But even though Fawkes is the most recognizable symbol of the Gunpowder Plot, he was only one of 13 men involved in its planning. And this group was far from the only one that wanted to take down King James I.

The Events That Incited The Gunpowder Plot Of 1605

For a significant portion of its history, England had close ties to the Catholic Church. But then, in 1534, King Henry VIII wanted to annul his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, and the Pope refused to approve of the annulment.

Determined to end his marriage with or without the Pope’s approval, Henry VIII established himself as the Supreme Head of the Church of England. From there, England began to shift from Catholicism to Protestantism.

Then, over half a century later, another king began to rise to power, King James VI of Scotland. James was the son of Mary, Queen of Scots, a disgraced Catholic monarch who would eventually be beheaded for posing a threat to her cousin, the reigning Protestant Queen Elizabeth I.

Despite this, Elizabeth named James heir to the throne on her deathbed, and he then became King James I of England in 1603. But as History UK outlines, James’ past held a few warning signs of things to come.

Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesIn 1600, the Gowrie family in Perth allegedly attempted to assassinate King James I (then James VI).

In 1597, James published a treatise on witchcraft and magic called Daemonologie, which studied the alleged influence of demons on the common folk and outlined a number of other supernatural subjects.

Evidently, James had an intense fear of the occult. He even went so far as to claim that a coven of witches had cast a spell back in 1589 to summon a storm that terrorized the then 23-year-old king, shortly after he decided to marry Anne of Denmark (who was just 14 years old at the time).

He was also the royal behind the King James Bible, notable for a few reasons, but in particular for the inclusion of sodomy as one of several “horrible crimes which ye are bound in conscience never to forgive” — even though James himself had numerous male lovers throughout his life.

The King James Bible also came after a three-day conference at Hampton Court in Surrey, during which James angered both Catholics and Protestants by rejecting ideas from both sides on which direction to take the country.

In 1603, this anger culminated in the “Bye Plot,” an attempt from Catholics and Puritans to arrest and replace the king — and though it ultimately failed, it served as a precursor to the much more infamous Gunpowder Plot.

The Conspirators Who Tried To Assassinate The King — And Why They Failed

Although King James I initially seemed sympathetic to English Catholics, that notion was quickly tossed aside when he said in a 1604 speech to Parliament that he, according to Royal Museums Greenwich, “detested” the Catholic faith (even though his wife was a Catholic herself).

This was particularly troublesome for English Catholics following the harsh religious persecution they faced under the rule of Queen Elizabeth I.

In particular, James’ declaration drew ire from a devout Catholic named Robert Catesby, whose father had been persecuted for refusing to conform to the Church of England throughout Elizabeth’s reign.

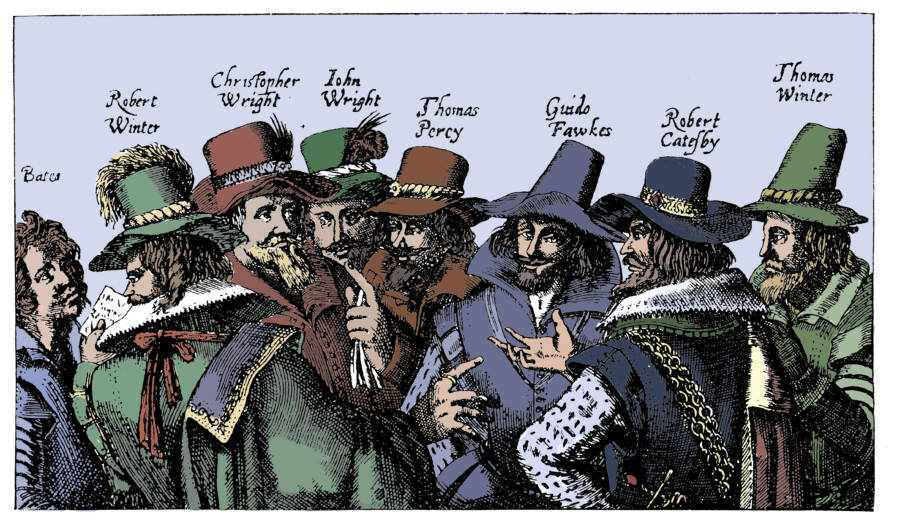

Print Collector/Getty ImagesAn illustration of Guy Fawkes and the other Gunpowder Plot conspirators.

Hoping to put an end to the Catholic persecution, Catesby began to meet in secret with other Catholics to plan James I’s assassination. After James’ death, the conspirators hoped to install his daughter, Princess Elizabeth, as a puppet monarch and re-establish Catholic rule in the country.

The group of conspirators, which included 13 men, first met on May 20, 1604, and swore an oath of secrecy as they started to lay out the Gunpowder Plot. Among them was the zealous Catholic convert Guy Fawkes, an explosives expert who had once fought in the army of Catholic Spain.

The group’s initial plan was to tunnel beneath the Houses of Parliament, rig the tunnel with explosives, and detonate them. However, in 1605, they managed to instead rent out a cellar directly beneath the House of Lords, a significantly more strategic (and convenient) location for the explosion.

The new plan was for Fawkes to enter the cellar, which now contained barrels of gunpowder, during the Opening of Parliament on November 5, 1605. However, just days before, on October 26th, the brother-in-law of one of the conspirators, Lord Monteagle, received an anonymous letter.

It was a warning to Monteagle: Do not attend the Opening of Parliament.

Monteagle then handed the letter over to Robert Cecil, James I’s chief minister. Meanwhile, the conspirators were made aware that Monteagle had received the letter. They opted to continue with the plan, anyway.

The Fateful Capture Of Guy Fawkes

When King James I returned from a hunting trip in Cambridgeshire on November 1st, Cecil showed him the letter. A few days later, on November 4th, James’ men conducted a thorough search of the Parliament cellars and came across a cache of firewood — and Guy Fawkes along with it.

Universal History Archive/Getty ImagesFawkes was tortured for his role in the Gunpowder Plot, but he avoided execution by dying on his way to the gallows.

Fawkes told the men that his name was John Johnson, and the firewood belonged to his master, a known Catholic agitator named Thomas Percy. This did little to convince them of his innocence, and soon afterward, in the wee hours of November 5th, James I ordered another search of the vaults.

Once again, Fawkes was discovered, alongside 36 barrels of gunpowder. This time, he was carrying fuses and matches. Fawkes was quickly arrested.

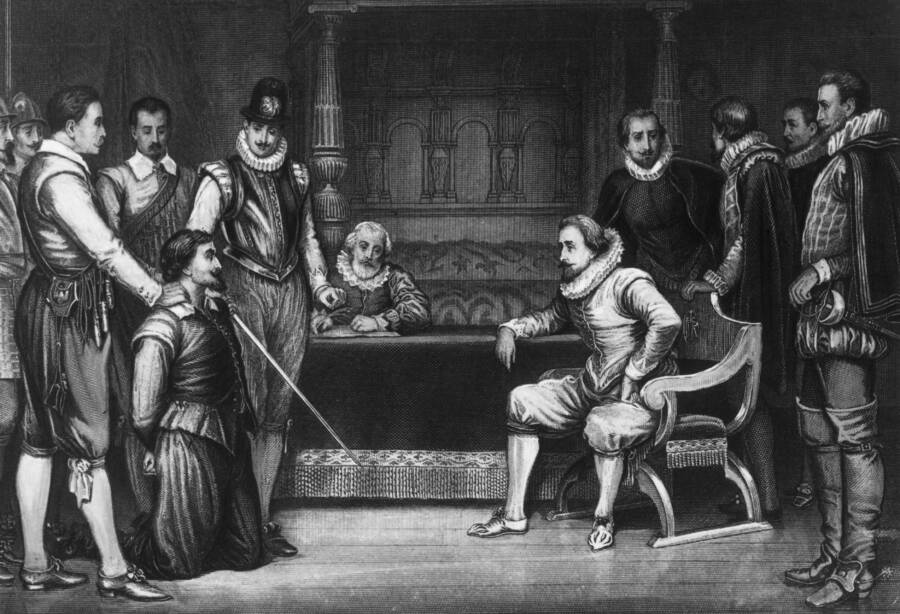

According to History, Fawkes was then tortured by the authorities. Eventually, Fawkes confessed that he was part of an English Catholic conspiracy to eliminate the Protestant leadership. He also revealed the names of his co-conspirators — each of whom soon attempted to flee.

Catesby, Percy, Jack Wright, and Kit Wright were all killed during their attempted escapes. The remaining eight conspirators were arrested and then taken to the Tower of London to await trial. One conspirator, Francis Tresham, died of health issues before he could be tried.

Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesAn illustration depicting King James I interrogating Guy Fawkes about his involvement in the Gunpowder Plot.

On January 27, 1606, the surviving men were found guilty of treason and sentenced to be hanged, drawn, and quartered.

Conspirators Sir Everard Digby, Robert Wintour, John Grant, and Thomas Bates were executed in St. Paul’s Churchyard on January 30th, with the remaining conspirators to suffer the same fate a day later in the Old Palace Yard at Westminster.

That’s what happened to Thomas Wintour, Ambrose Rookwood, and Robert Keyes. Fawkes, however, managed to avoid that agonizing execution.

Unfortunately for him, he did so by either jumping or falling from a ladder while climbing the gallows — and fatally snapping his neck during the fall.

The Significance Of Bonfire Night In Britain

On the one-year anniversary of the attempted assassination, Parliament established that November 5th would be celebrated as a day of remembrance of the failed plot. Celebrations, especially church services, were mandatory in the country, and each member of every congregation was asked to give thanks that the Gunpowder Plot had failed.

The requirement for attending church on that day has since gone away, but the yearly celebration itself has not. Each year on November 5th, people across the U.K. commemorate the day by lighting bonfires or fireworks.

Roger Viollet Collection/Getty ImagesAn illustration of the execution of the Gunpowder Plot conspirators.

Many still burn effigies of Guy Fawkes, which is why Bonfire Night is also often referred to as Guy Fawkes Night (or Guy Fawkes Day).

Following the Gunpowder Plot, Parliament also established a ceremonial search in the days leading up to the State Opening of Parliament, in which the Yeomen of the Guard check the buildings and cellars to ensure that no explosives have been planted, among other potential security threats.

Still, it is a bit ironic that Guy Fawkes’ image has become so synonymous with anarchy and rebellion in modern times. At the end of the day, he was just one of 13 men who failed to assassinate King James I.

After learning about the Gunpowder Plot, read the story of the German general who led a failed assassination plot against Adolf Hitler. Then, learn about some of the most dramatic assassination attempts ever carried out against American presidents.