Pablo Escobar's cousin and right-hand man, Gustavo Gaviria wielded untold power behind the scenes while helping to run the Medellín Cartel, until he was killed by Colombian police in 1990.

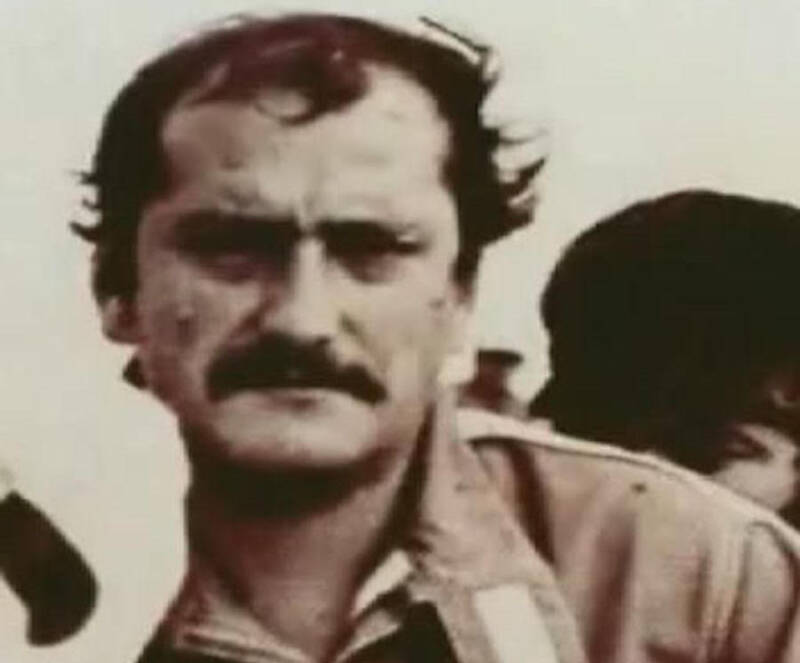

Wikimedia CommonsPablo Escobar’s cousin Gustavo Gaviria (left) in an undated photo. Unlike Escobar, Gaviria stayed out of the spotlight.

Ever since Pablo Escobar’s death in 1993, the Colombian drug lord has inspired TV shows like Narcos, movies like Paradise Lost, and books like Kings of Cocaine. But while “El Patrón” was the kingpin of the Medellín Cartel, Pablo Escobar’s cousin Gustavo Gaviria was arguably the real mastermind.

“[Gaviria] we really wanted to take alive because he was the true brains,” said Scott Murphy, a former DEA officer who investigated the Medellín Cartel in its final years. “He knew all about the labs, where to get the chemicals, the transportation routes, [and] the distribution hubs throughout the United States and Europe.”

From 1976 to 1993, the Medellín Cartel ruled the cocaine business. And Pablo Escobar attracted plenty of attention as the main “boss” of the operation. But behind the scenes, Gaviria reportedly oversaw the financial side of the empire — at a time when the cartel could pull in $4 billion per year.

So who was Gustavo Gaviria, Pablo Escobar’s cousin and the shadowy figure behind much of the Medellín Cartel’s success?

The Family Ties Between Gustavo Gaviria And Pablo Escobar

NetflixPablo Escobar portrayed by Wagner Moura (left), and Gustavo Gaviria portrayed by Juan Pablo Raba (right) in the Netflix series Narcos.

Gustavo de Jesús Gaviria Rivero was born on December 25, 1946. Almost exactly three years later, his cousin Pablo Emilio Escobar Gaviria was born on December 1, 1949.

The boys grew up close in the Colombian town of Envigado. According to Mark Bowden, author of Killing Pablo: The Hunt for the World’s Greatest Outlaw, both Gustavo Gaviria and Pablo Escobar had well-educated parents and were solidly middle-class — which made their decision to leave school and pursue a life of crime “deliberate and kind of surprising.”

“Pablo began his criminal career as a petty thug in Medellín,” explained Bowden. “He and Gustavo were partners in a number of petty enterprises.”

Escobar’s son, Sebastián Marroquín, recalled that Gustavo Gaviria and Pablo Escobar were “always looking to do some business or pull off a crime to get some extra money.”

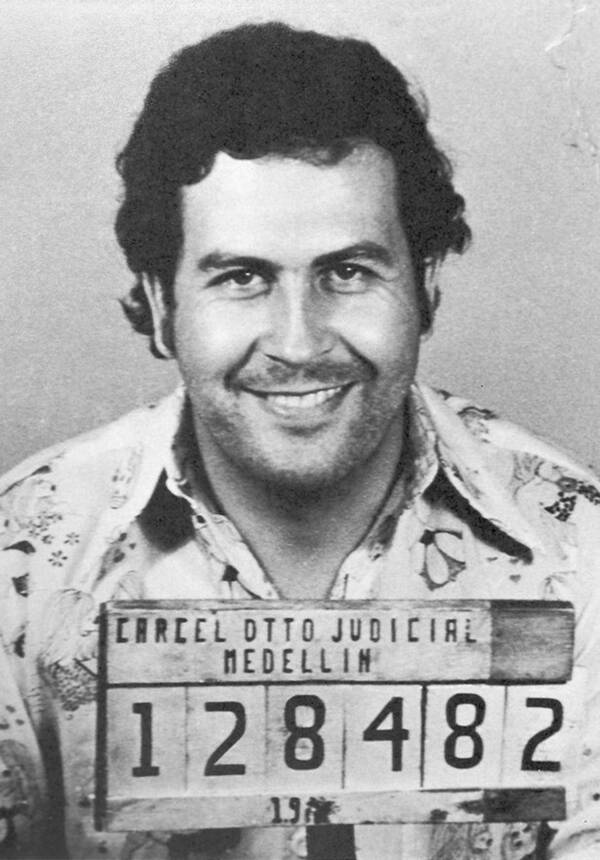

Wikimedia CommonsPablo Escobar (pictured) and Gustavo Gaviria were both arrested in the 1970s.

The cousins stole tires and cars and robbed cinema box offices. They even stole headstones from graveyards and held them for ransom. Eventually, they graduated from kidnapping gravestones to kidnapping living people — in one case, an industrialist whom they held for ransom.

The cousins’ criminal habits didn’t go unnoticed. In the 1970s, both Gustavo Gaviria and Pablo Escobar were arrested.

Everything changed after that arrest. The cousins turned toward a bigger prize than what they could fetch by ransoming tombstones — cocaine.

After their arrest, “[Escobar and Gaviria] essentially built everything together,” noted Douglas Farah, who covered Colombia as a journalist toward the end of Escobar’s reign.

Everything they had done up to that point would pale in comparison.

A Life Of Crime And Cocaine

YouTubePablo Escobar, far right, sits with a group of his close Medellín “family” members.

By the 1980s, demand for cocaine in the United States had skyrocketed. In Colombia, Gustavo Gaviria and Pablo Escobar were prepared to meet it.

Escobar had already sensed an opportunity in the early 1970s, when the cocaine market moved north from Brazil, Argentina, and Chile. He began smuggling coca paste into Colombia, where he had it refined, then sent north with “mules” to be sold in the United States.

When the ’80s hit — the era of discotheques and Wall Street binges — Escobar, Gaviria, and their Medellín Cartel were ready.

Escobar was the undisputed leader of the operation. But Gaviria handled the finances and exportation of cocaine behind the scenes. Pablo Escobar’s cousin was the “brains of the cartel,” according to former DEA officer Javier Peña, who tracked Escobar from 1988 until the drug lord’s death in 1993.

The cousins had different strengths, which they utilized in different ways. Gustavo Duncan Cruz, a political science professor at EAFIT University in Medellín, explained that Pablo Escobar focused on the violence of the cocaine trade. His charisma helped inspire his army of sicarios or hitmen. Anyone who disobeyed Escobar’s orders was intimidated by violence.

Gaviria handled a different side of things. “Gustavo was more specialized in business,” Cruz said. “Illegal business, of course.”

When one of the cartel’s main trade routes — through the Bahamas to Florida — was disrupted, Gaviria didn’t panic. He got creative.

Instead of flying cocaine north, Gaviria used legitimate cargo ships carrying appliances. Cocaine was stuffed into refrigerators and televisions. According to the Wall Street Journal, it was also mixed into Guatemalan fruit pulp, Ecuadorian cocoa, Chilean wine, and Peruvian dried fish.

The smugglers even went as far as soaking cocaine into blue jeans. Once the jeans arrived in the U.S., chemists pulled the drug out of the denim.

The cartel made so much money — a kilo of cocaine cost about $1,000 to make but could be sold for up to $70,000 in the U.S. — that pilots carrying the drug flew one-way north, ditched their planes in the ocean, and swam to waiting ships.

By the mid-1980s, the Medellín Cartel could rake in up to $60 million per day. At the height of their power, Pablo Escobar and Gustavo Gaviria had cornered 80 percent of the cocaine supply in the United States.

“Gustavo Gaviria had the contacts all over the world for the cocaine distribution… [He] was the one,” said Peña.

But it wouldn’t last.

The Downfall Of Pablo Escobar’s Cousin, Gustavo Gaviria

YouTubeAccording to police, Pablo Escobar’s cousin Gustavo Gaviria was killed in a shoot-out. But Escobar believed that he was kidnapped and tortured before being executed.

By the 1990s, the Medellín Cartel and the Colombian government were in open war.

Pablo Escobar had tried to create an aura of legitimacy around himself and his business. He became a Colombian “Robin Hood” and built schools, a soccer stadium, and housing for the poor. In 1982, he was elected to the Colombian parliament and held dreams of running for president one day.

“[Escobar] spent a lot of time on his campaign trail and essentially left Gaviria to run the business side of things,” noted Douglas Farah.

Gaviria seemed to be happy behind the scenes.

“Most people think drug traffickers want money, but some of them want power,” said Cruz. “Pablo wanted power. Gustavo was more for the money.”

But Escobar was forced out of parliament by Justice Minister Rodrigo Lara Bonilla due to his activity in the drug trade. Bonilla threatened to go after the Medellín Cartel — and ultimately paid with his life.

Bonilla’s death triggered a “war” on drug traffickers like Escobar and Gustavo Gaviria. Over the next decade, the Medellín Cartel fought back — killing politicians, bombing airplanes, and attacking government buildings.

On August 11, 1990, the Colombian government struck a decisive blow. The police tracked down Gustavo Gaviria in a high-end Medellín neighborhood and killed him.

“When Gustavo was killed, the police claimed it was in a shoot-out,” noted Bowden. “But Pablo always claimed he’d been kidnapped, tortured, and executed.”

“I think the expression ‘killed in a shootout’ kind of became a euphemism,” Bowden added.

The death of Pablo Escobar’s cousin sent shockwaves throughout Colombia. It shattered a fragile peace agreed upon by the cartels and by the new Colombian president, César Gaviria, and sent the country spinning into several more years of horrific violence.

“That set off the war that really wreaked havoc,” Bowden said.

The death of Gustavo Gaviria would also spell the end for Pablo Escobar. Without his business partner, Escobar’s hold on the cartel began to fall apart. The drug trafficker went on the run.

On December 2, 1993, Pablo Escobar was killed by Colombian police.

After reading about Gustavo Gaviria, check out these rare photos of Pablo Escobar. Then, take a look at these Instagram photos from Mexico’s most feared cartels.